IS NOT EMBARRASSING: KIPPENBERGER AS EXEMPLARY SUBJECT Tom McDonough on “Martin Kippenberger: Everything is Everywhere” by Chris Reitz

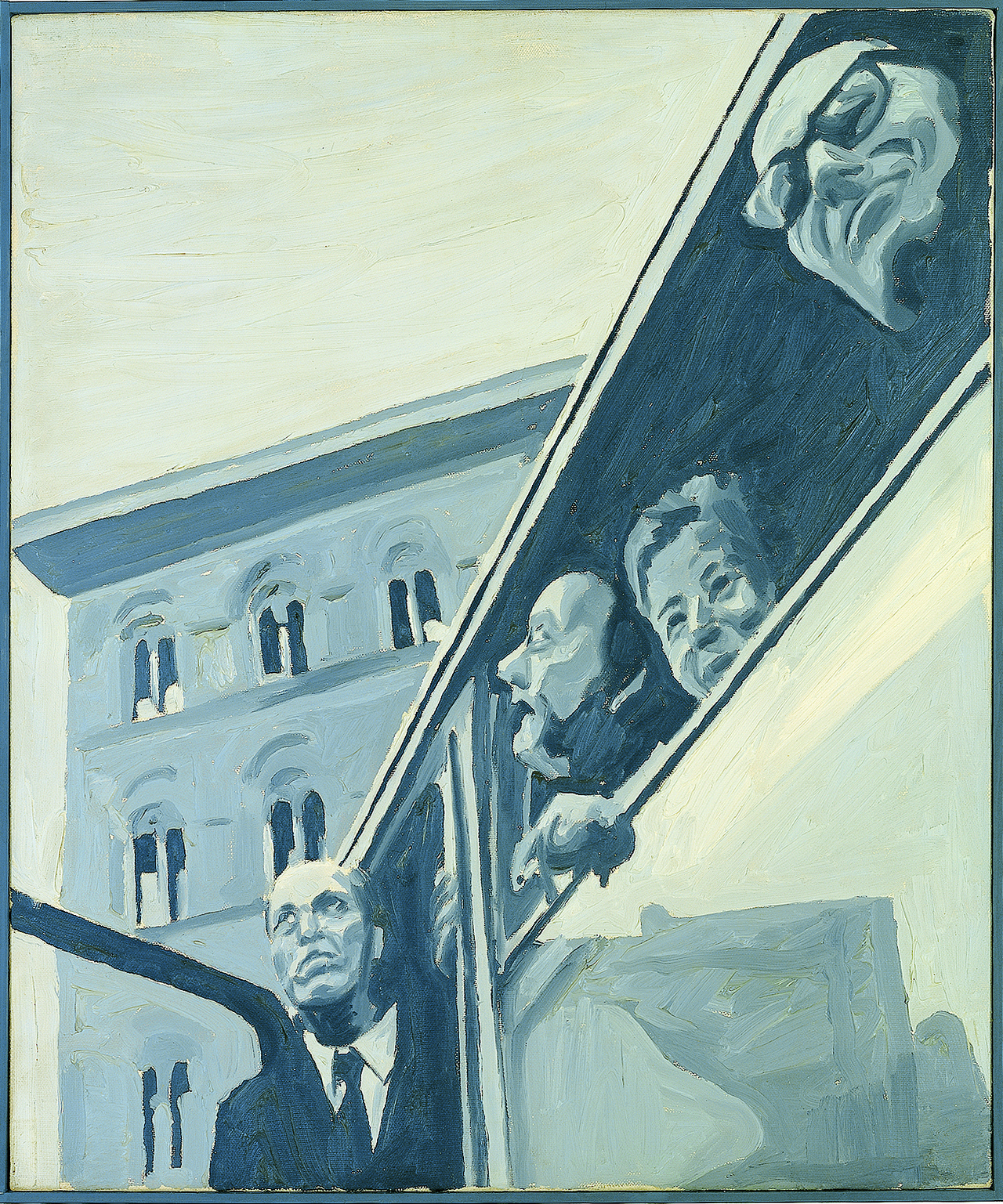

Martin Kippenberger, “Unitled,” 1981

It seems fair to say that American art historians, for the most part, have never quite managed to get their heads around Martin Kippenberger’s art. Yes, there was the brilliant retrospective organized in 2008 by Ann Goldstein, which toured from Los Angeles to New York. [1] And yes, in the last decade collectors here have pushed his auction prices into the eight-figure range. [2] But critics and historians have more often been at a loss for convincing frameworks within which to discuss his work. When he first exhibited in New York, in the mid-1980s, German painting meant Neo-Expressionism, a polarizing style that had already been denounced as a “cipher of regression.” It’s telling that one of the few reviews of Kippenberger’s first appearance in the US – in a 1984 show at Metro Pictures alongside his Cologne associates Werner Büttner, Albert Oehlen, and Markus Oehlen – was by Donald Kuspit, a champion of the new German painting, who quickly categorized his work as little more than a sort of farcical, bohemian, scatological nihilism. [3] When Kippenberger exhibited paintings at the gallery in a solo presentation six months later, it went effectively unremarked in the press. With very few exceptions, this would remain the case for some time: the wide range of his activities – from paintings and sculptures to books, posters, installations, and performances – and his often-cryptic (and humorous) references to local artistic “scenes” in Berlin and Cologne have made his work rather recalcitrant to translation into dominant American interpretive paradigms. [4] Chris Reitz acknowledges as much toward the end of his compelling new book on the artist, Martin Kippenberger: Everything Is Everywhere (MIT Press, 2023; hereafter, MK), when he describes how, as criticism in the 1980s was split between “celebrations of artistic expression and critiques of authorial autonomy,” Kippenberger couldn’t help but “dodge characterization” (MK, 226). Reitz’s signal accomplishment in this, the first scholarly book in English dedicated to the artist, is precisely to provide his readers with a convincing reading that allows him to guide us through the career of a figure he credibly judges to be “the most provocative and revealing artist of West Germany in the 1970s and 1980s” (MK, 18). [5]

Across five chapters, Reitz – who currently teaches critical curatorial studies at the University of Louisville and directs its Hite Institute of Art + Design – steers us through major bodies of work that defined Kippenberger’s trajectory: Uno di voi, un tedesco en Firenze (One of You, a German in Florence) – his breakthrough series of grisaille paintings, mostly portraits based on photographs, produced while residing in Florence in 1976, after he had abandoned art school in Germany; Lieber Maler, male mir (Dear Painter, Paint for Me), a series of realist canvases made by a professional billboard painter commissioned by the artist in West Berlin in 1981; Die I.N.P.-Bilder (The I.N.P. Pictures, whose initialism stands for ist nicht peinlich, “is not embarrassing”) of 1984, with their satirical references to the Cologne art scene and West German culture more generally; and out to the world at large, with his Peter sculptures of 1987, which mimicked conventions of the display and crating of artworks; and finally his last work, from 1994, The Happy End of Franz Kafka’s “America”, a room-scaled installation of office furniture that sought to provide a sort of conclusion (if highly ambiguous) to this famously unfinished book.

Martin Kippenberger, “Untitled (Whistlestop Tour),” 1976–77

Yet Reitz’s aim here is less to give a comprehensive overview of the artist’s work than to situate him at the crossroads of a number of influential discourses. This entails, on the one hand, exploring his relation to other artists and their work; the author does a superb job in placing Kippenberger within his German context and offers many insightful discussions of his antagonistic, ironic, but not to say at times cynical approach to his contemporaries and members of an older generation – references cleverly encoded in his work and expertly unpacked by Reitz. [6] The same is true, on the other hand, of the artist’s frequent allusions to the middlebrow culture of postwar West Germany, its Wirtschaftswunder proliferation of goods, and its construction of a new lifestyle of consumption. Indeed, Kippenberger’s “compulsive citationality,” his enfolding of references “to his immediate predecessors and current events into a [...] complex matrix of contemporary West German reference” (MK, 107), is a significant theme for Reitz, a means whereby the artist positioned himself in relation to both a shifting art market and an evolving social world. Both, Reitz argues, are inextricably linked to the emergence of the neoliberal order, understood as more than a simple valorization of the free market, but rather, in Foucauldian terms, as a new regime of self-production, in which we must invest in our own human capital and become entrepreneurs of our selves (MK, 69, 74-75). Kippenberger, in Reitz’s reading, simultaneously partakes of this neoliberal subjectivity and develops a set of aesthetic strategies to hold it at a distance, in artwork that “promises comprehensibility [but] never delivers,” declining to yield to those demands for legibility enforced by an ever-more-powerful art market. “The misinterpretive logic and coding of his citationality,” Reitz insists, “refuses the uninhibited connectivity and translatability demanded by the market into which it entered” (MK, 133).

This is a major shift in the critical discourse around Kippenberger and a generational break from interpretive paradigms developed by those who were close to the artist. Reitz first essayed this reading in his 2015 dissertation “Martin Kippenberger and Mike Kelley: The Artist Persona and the Precarious Middle Class,” written at Princeton under Hal Foster. Already in this initial iteration, we find his interest in situating a generation of artists that came of age in the 1970s in relation to wider sociocultural shifts: both the rise of a neoliberal economic regime, with its accompanying vision of the human subject as itself a site of capital accumulation, and transformations within the economic and institutional structures of the contemporary art world and its market, which saw their ever-greater assimilation to the demands of global commodity circulation. Faced with this narrowing of autonomy, Kippenberger adopted something like that Dadaist paradigm of mimetic adaptation first identified by Foster: “the work mimics and exacerbates the conditions [of commodity exchange within the art market] in which the artist finds himself,” even if, however, it simultaneously participates “in the very structures that it mocks” (MK, 164).

“Martin Kippenberger: Peter. Die russische Stellung,” Galerie Max Hetzler, Cologne, 1987

It is here, I think, that we sense the contemporary import of Reitz’s understanding of Kippenberger. For as much as this is a grounded, historical study, it also provides the reader with something like a prehistory of today’s global, networked art world, and one artist’s (exemplary) response to it. Kippenberger never claimed to stand outside of that system, or to critique it; he remained caught within a dialectic of misery and enthusiasm – to evoke two terms central to both the artist and his interpreter – like the good kleinbürgerlich subject he was. Yet it was precisely this immersion, this refusal of a position of political or aesthetic purity, that created the conditions for an art that could deeply inhabit, and therefore represent, those unexplored “feelings of identity fragmentation and inauthenticity” — to quote Reitz from a 2013 assessment of Kippenberger’s reception, which appeared in the pages of this journal — that could be said to constitute the bedrock subjective experiences of late capitalist postmodernity. [7] His art, along with the concrete forms of sociability he fostered in Berlin, Cologne, and elsewhere, offers us an influential model for approaching these conditions, within the context of a marketplace that in his lifetime was expanding from something determinedly local and regional to international. That is, Reitz gives us a distinctly 21st-century Kippenberger – not as an artist to be unproblematically celebrated, but as one to be carefully and sympathetically understood. [8] With Everything is Everywhere, Kippenberger has finally found his American interlocutor, a quarter century after his death.

Chris Reitz, Martin Kippenberger: Everything Is Everywhere, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2023, 244 pages.

Tom McDonough is an art historian, critic, and professor at Binghamton University, State University of New York. He is the author of several books on art and cultural theory.

Image credit: 1. Photo: Bernhard Schaub, 2. Photo: A. Burger, 3. Photo: unknown; all images © Estate of Martin Kippenberger, Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne

Notes

| [1] | “Martin Kippenberger: The Problem Perspective,” the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, September 21, 2009–January 5, 2009 and the Museum of Modern Art, New York, March 1–May 11, 2009. See also the accompanying catalogue, Ann Goldstein, Martin Kippenberger: The Problem Perspective (Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art; Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008); and George Baker, “Out of Position,” Artforum 47, no. 6 (February 2009): 142-151. |

| [2] | On the market for Kippenberger’s paintings, see Nate Freeman, “The Kippenberger Conundrum: How the Wildly Prolific Artist’s Artist Became an Eight-Figure Auction Darling,” ARTnews, January 8, 2018, |

| [3] | Donald Kuspit, “Reviews: New York: Werner Büttner, Martin Kippenberger, Albert Oehlen, Markus Oehlen, Metro Pictures,” Artforum 23, no. 5 (January 1985): 90. For a complex reflection on Kippenberger’s relation to Neo-Expressionist painting, see Isabelle Graw, “Conceptual Expression: On Conceptual Gestures in Allegedly Expressive Painting, Traces of Expression in Proto-Conceptual Works, and the Significance of Artistic Procedures,” in Art after Conceptual Art, ed. Alexander Alberro and Sabeth Buchmann (Vienna: Generali Foundation; Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006), 119-134. |

| [4] | A significant, early exception being Stephen Ellis’s in-depth exploration of the Cologne scene, and Kippenberger, Albert Oehlen, and Georg Herold in particular: “The Boys in the Bande,” Art in America 76, no. 12 (December 1988): 110-125, 167, 169. Ellis, a painter, had lived in Cologne from 1986 to 1988, giving him firsthand access to work that remained otherwise largely opaque to American audiences. |

| [5] | English-language readers have largely been limited to exhibition catalogues – including notably the aforementioned MOCA publication and that from Tate Modern’s 2006 retrospective – a translation of Susanne Kippenberger’s biography, and, at a more rarified level, the four volumes of the catalogue raisonné of the artist’s paintings. |

| [6] | One thinks of the important work done by Diedrich Diederichsen in this regard; see for example his “The Poor Man’s Sports Car Descending a Staircase: Kippenberger as Sculptor,” in Goldstein, Martin Kippenberger: The Problem Perspective, 118-183. |

| [7] | Chris Reitz, contribution to Isabelle Graw, “Still One of Us?” Texte zur Kunst, no. 90 (June 2013): 178. |

| [8] | Something similar could be said of Reitz’s long essay “Maurizio Cattelan’s Managerial Spirit,” perhaps the best piece of critical writing on its subject. |