What makes a system? Where does it begin and end? As a pioneer of Institutional Critique, Hans Haacke has spent a career showing us the inner workings of capitalism’s cultural wheels. But a recent exhibition at New York’s New Museum made the case for taking the macro view on his work, its focus on systems, and its place within a wider social and political context. Artist Melanie Gilligan reports.

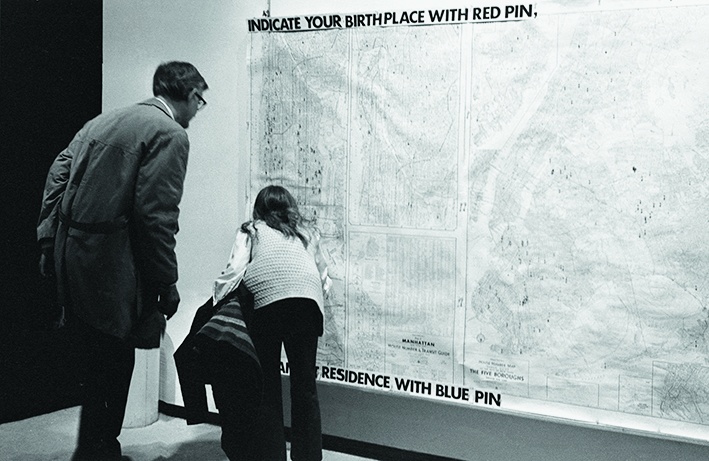

The much-discussed retrospective “Hans Haacke: All Connected” at the New Museum introduces the viewer to several early bodies of the artist’s work, all of which came before his pioneering Institutional Critique projects. One of these periods is given particular prominence in the exhibition, with a whole floor dedicated to it: Haacke’s physical and biological systems. Critics who pay attention to Condensation Cube (1963–1965) to the exclusion of the rest of Haacke’s physical systems works may agree with Benjamin Buchloh’s dismissal of Haacke’s systems theory-inflected production, yet the continuity of this work with the rest of his practice is emphasized in the main wall text, which refers to Haacke’s subsequent work as “real-life social, political and economic systems.” This continuity is also communicated through the juxtaposition of a gallery of physical and biological systems works alongside a large-scale piece that could easily be called an analysis of a social system, Gallery-Goers’ Birthplace and Residence Profile, Part 1 (1969) and Part 2 (1970), which mapped the housing locations and conditions of visitors to Haacke’s exhibition at the Howard Wise Gallery. Meanwhile, John A. Tyson’s essay for the New Museum show’s catalogue includes a quote describing systems as Haacke’s “career long primary interest.” Even the exhibition title chimes with a systems-theory approach that tends to focus on the interrelation of phenomena. All of this suggests that this exhibition is prominently foregrounding the idea of systems in Haacke’s work, or even in fact asks the viewer to see all of Haacke’s work as systems.

Tyson’s essay goes on to confront the limitations of a systems-theoretical approach in accounting for all of Haacke’s work. Yet despite this, and substantial questions about systems theory’s link to military technoscience, I still find Haacke’s focus on the interconnection of systems especially compelling, given that so many interrelated political problems currently present themselves in this way. For instance, critical works such as MetroMobiltan (1985) and Upstairs at Mobil Musings at a Shareholder (1981, not in the exhibition) are especially thought-provoking in light of the urgent need to discuss the correlations between systemic racial oppression and economic exploitation. It even seems likely that Haacke’s propensity to make connections across different spheres, along with his politicization through the social movements of the late 1960s, led to his revelatory first “real-time social systems,” which polled viewers in art galleries and institutions in order to connect them and those works to the world outside the sphere of art. Here, constructing an understanding of living conditions and political behaviors outside of art was of essential importance for Haacke, and this continues throughout his politically committed career.

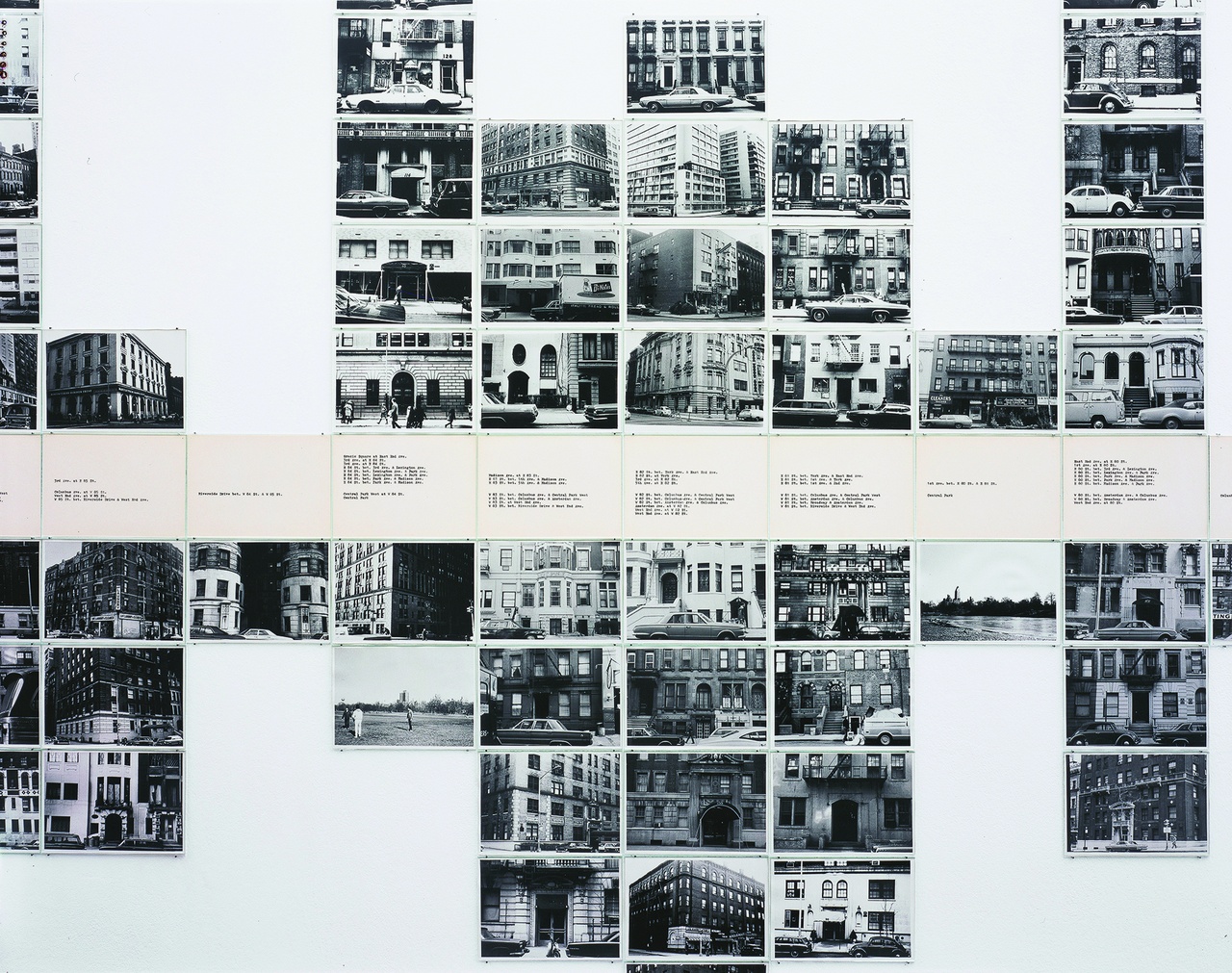

Perhaps the most system-like of Haacke’s politically focused works is Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, a Real Time Social System, As of May 1, 1971 (1971), which clearly shows how economic and social systems interrelate. In reference to this piece, Rosalyn Deutsche points out that Haacke photographed each building according to its property boundaries, thus affirming its “commodity character.” In so doing, he diagrams each sale and purchase in order to show the landlord’s accumulation strategy. Here we might pause to ask: How does thinking through systems give Haacke an important perspective on socioeconomic phenomena? In the piece, Haacke illuminates a system of economic profit built on deplorable social conditions. The landlord Shapolsky increases profit by extracting rent while refusing to pay for upkeep. The outcomes of this neglect are imposed on tenants not adequately protected against such abuse, many of them people of color. Deutsche confirms that Haacke is able to show the structurally determined dimensions of these dealings. According to Deutsche, by exceeding “the limits of the investigation of the Shapolsky family relations,” Haacke’s work “becomes a critique of social relations of property.” In other words, one realizes that this particular investment strategy used by many landlords has a systemic dimension, in that there are interconnected practices of systemic racism in the rental of private housing, and that this works in conjunction with operations enforced by property relations.

Yve-Alain Bois points out that Haacke, in much of his work, “simply provides information.” The artist exposes information that shows systems of power both in the art world and outside of it; connecting networks of capital accumulation based on oppression and violence. One of the strengths of thinking through Haacke’s works as systems is that you can trace systems that connect transactions to political decisions. In his work Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Board of Trustees (1974), this approach amounts to a powerful condemnation, wherein the museum’s board members were scrutinized, revealing one of the them to be associated with a company opposed to the Allende government in Chile because of economic interests. The exhibition shows how collecting information is a powerful tool in Haacke’s hands. Whether through an artwork such as 1978’s A Breed Apart, which targeted Leyland (the parent company of Land Rover) for aiding the South African apartheid government (and which anti-apartheid activists adopted for their cause), or by tracing the provenance of Seurat’s Les Poseuses in order to reveal the painting’s history of repeatedly changing hands (eventually finding its way into the ownership of an art investment company), Haacke has for decades now been committed to exposing how the powerful are implicated in systems of domination and expropriation.

Haacke has stated that he uses context as a material. What the artist chooses to include as context is of paramount importance. This coincides with what Haacke’s close friend, the critic and curator Jack Burnham, has said in his writing on system aesthetics, namely that “in evaluating systems, the artist is a perspectivist considering goals, boundaries, structure, input, output, and related activity inside and outside the system.” In other words, the system Haacke looks at is only bounded by the artist’s decisions.

There was one overwhelming political context that should perhaps have been addressed in “Hans Haacke: All Connected,” however: during the period before Haacke opened this exhibition, the staff at the New Museum were preparing to go on strike. Their previous decision to unionize represents one of the more significant and well-publicized changes in labor-organizing efforts to have occurred in the US art context in recent years. In the end, the staff negotiated a new contract and the strike did not happen, but it was notable that Haacke did not find a way to comment on the context of the labor dispute or incorporate it into his exhibition in some way. After all, labor is one of the most important factors of the contemporary capitalist system, and it is also a part of the context of his show.

“Hans Haacke: All Connected,” New Museum, New York, October 24, 2019–January 26, 2020.

Notes