MIXED SIGNALS Amin Alsaden on “Signals: How Video Transformed the World” at the Museum of Modern Art, New York

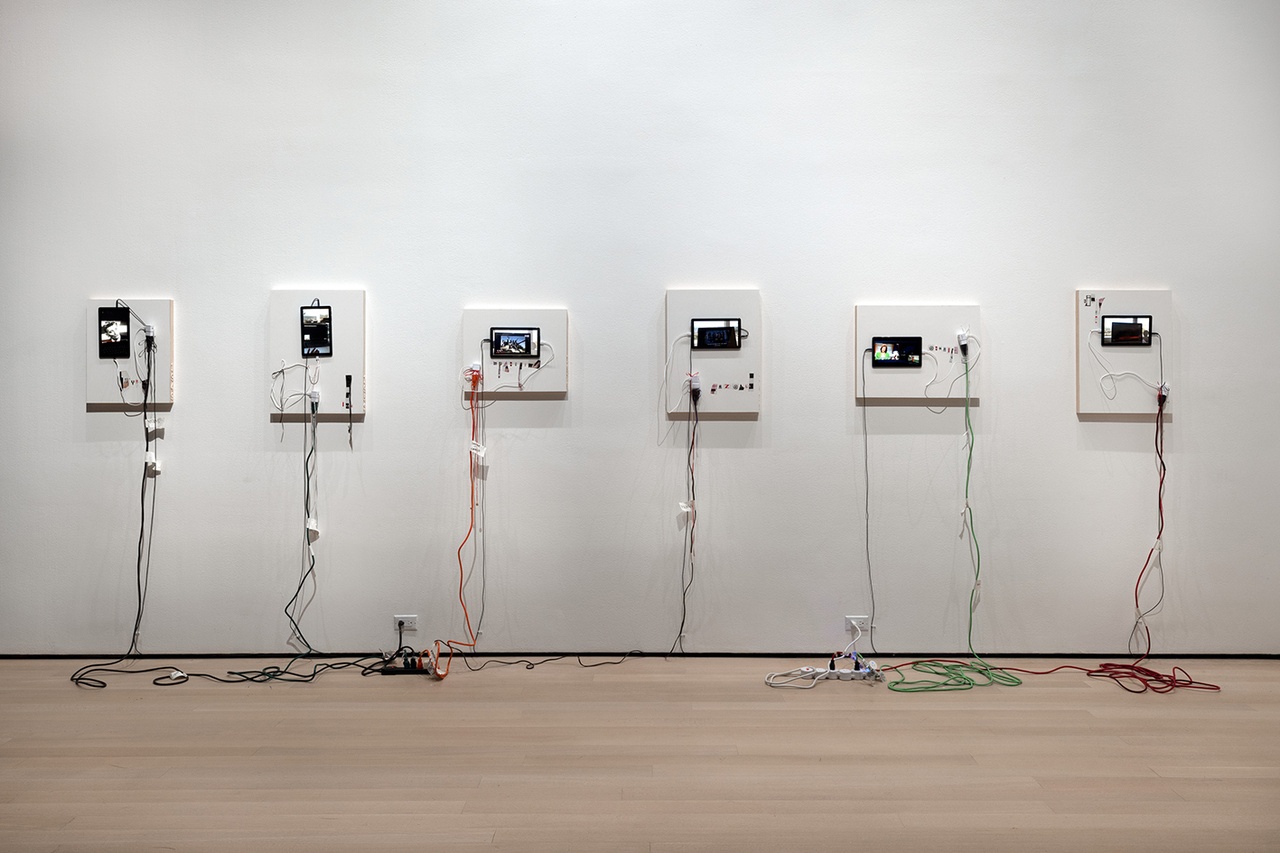

Frances Stark, “U.S. Greatest Hits Mix Tape Volume I,” 2019

A cacophony of sounds and barrage of moving images, in the otherwise hermetically sealed spaces, refreshingly conjure the bustling city outside. But the works are displayed neatly and discretely across the white walls, in a cerebral assembly that aims to convey a particular message. What is being transmitted by “Signals: How Video Transformed the World,” however, is not entirely clear.

This massive group exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, ostensibly attends to the politics of video – how the ubiquity of the medium contributes to shaping contemporary public opinion. While it comes across as a comprehensive historical survey, the show brings together a rather specific selection: more than 70 works, mostly drawn from MoMA’s permanent collection, capturing six decades of artistic production, with an emphasis on the democratic potential of time-based media.

A dazzling array of works in a wide variety of formats is organized under thematic, and mostly chronological, rubrics. These include the grouping “Live and Direct,” which asserts how video differs from other artistic mediums – often experienced live, and diffused to distant places. A highlight in this category is Wipe Cycle (1969/2022), an early installation by Frank Gillette and Ira Schneider. A grid of nine monitors invokes the insidious uses of video, confronting viewers with the fact that even museum visitors become the subject of live surveillance, including at MoMA itself, and get turned into images circulated and consumed just like recorded footage or news broadcasts.

Under “Electronic Democracy,” Frances Stark’s U.S. Greatest Hits Mix Tape Volume I (2019), an assemblage about the absurdity of mass media, speaks to radically different uses of video existing side-by-side, from trivial entertainment to coverage of deplorable US interventions in countries like Afghanistan, Iran, Libya, and Syria. Emily Jacir’s Ramallah/New York (2004–05), displayed on two adjacent flat screens, might not be as technically sophisticated as other installations, but its simplicity draws striking parallels between two presumably diametrically opposed cities, and humanizes life in Palestine with the kind of nuanced and non-reductive perspective rarely offered in mainstream coverage of conflict. Amar Kanwar, in the room-size installation The Torn First Pages (2004–08), alludes to the atrocities committed by Myanmar’s regime, conflating the traditional medium of the book with the transient quality of video to suggest that each clip is just a page torn from an illegible reality.

The last large grouping of installations, “Spaces of Appearance,” addresses the co-optation of video by global technological authoritarianism, the ways art may help reveal manifestations of power, and the possibilities of creating new visibility within otherwise overwhelming noise. New Red Order’s Culture Capture: Crimes against Reality (2020) speculates about digital repatriation of Indigenous objects; it insinuates that technology is capable of colonizing visuals, as well as cultures, and proposes that novel representational methods might counter that hegemony, especially in places that continue to ignore the genocide of Indigenous peoples.

New Red Order, “Culture Capture: Crimes against Reality,” 2020

Exiting the exhibition’s main spaces, visitors encounter a series of customized viewing platforms displaying over 30 videos grouped under other themes, such as territory, access, and viral circulation – with early works by artists like Mona Hatoum and Walid Raad. Visitors are also encouraged to view other works across MoMA that are presented in conjunction with the show. This is an impressive exhibition, the size of a small biennial, and several visits are needed to view all the works – for this reason, many of these videos have been made available through a special online channel.

Although ambitious, the exhibition does not claim to be an encyclopedic or even synoptic overview of video art. And unlike a biennial, it does not seem concerned with making polemical statements, sharing instead some broad observations. Equally, this show eschews experimental ways of displaying video works, where space might somehow be destabilized – which could meet the mercurial evasiveness of the medium halfway. What is clearly missing are more immersive presentations, which might explore the potential of moving images to undermine, and perhaps invigorate, the architectural envelope.

But there are other missed opportunities. I was curious about this show because I am always drawn to video – for reasons I cannot fully articulate. I work with artists who use the medium to express difficult and complex subject matter. Video is challenging in that it demands innovative handling and display methods. It also dates very quickly, and yet it can capture contemporaneity like no other medium. Moreover, it continues to urge me to reflect on how my lived experience of conflict, specifically the 1991 Gulf War, contrasts sharply with the way the world consumed that vicious attack on Iraq – changing our lives forever – mostly as a televised spectacle.

This is precisely where, for me, an exhibition like this becomes problematic. MoMA’s curatorial statement asserts that video changed the world. But whose world exactly? And whose politics are being privileged here? What is the positionality of this American institution, making such grand statements about the globe, without acknowledging the role this medium plays in the military-industrial complex? Or the centrality of video in the destruction of places like Iraq and Afghanistan – a medium integral to the technologies enabling the US Army’s planetary dominance, to which Stark alludes in her work, and also in the representation, and denigration, of “other” cultures? To what extent does this exhibition uphold existing systems of power, while posturing as an advocate of oppositional strategies pioneered by video art?

I cannot help but wonder why the exhibition does not ask who has been impacted the most by video; why there was no soul-searching into the reasons behind such disturbing blind spots at this premier American museum, with its brilliant and knowledgeable curators; why there was no affirmative inclusion of Iraqi, Afghani, Syrian, Yemeni, or Iranian artists, in other words, those hailing from countries that have suffered US hostilities, and where video plays an unprecedented role in both warfare and in resistance against unwarranted aggressions. The misleading scale of this exhibition should not obfuscate the fact that it is presenting a highly specific genealogy, one reminiscent of the canon MoMA has hypothetically started questioning lately – and canons, by default, imply exclusions.

“Signals: How Video Transformed the World,” Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2023, installation view

Considering US imperial adventures, as well as MoMA’s professed desire to fill glaring gaps in its collecting and exhibition strategies, an exhibition like “Signals” could have been a key opportunity for globalizing and diversifying the institution’s art historical and curatorial purview. Aside from the obvious omissions – which are always ideologically driven, even when the biases might be unconscious – it is perplexing why there was no research into pioneering video artists from “other” cultures, particularly the Muslim and Arab worlds, with which the West appears to be in constant clash. Muslims constitute a quarter of the planet’s population, and the US is a country with a serious Islamophobia problem that goes beyond political or military action; while I am making a point of highlighting the examples above, of artists who paid attention to the plight and representations of some Muslim-majority countries, it is troubling to not see a single Muslim artist who addresses these questions head on, from an explicitly Muslim perspective, in a show purportedly about the politics of video (with the exception of Kanwar, whose work touches upon the genocide of the Rohingya population in Myanmar).

Herein lies the contribution of a review, although too late to make a difference in the exhibition being reviewed. Writing a review teaches me to see with the attention and care that we cannot usually afford in our distracted lives, in an era oversaturated with dissonant signals. It is also an exercise in probing why I might appreciate certain things and not others – why some exhibitions resonate, and might warrant a review. It is a favor I do to myself, but it is also a courtesy extended to the artists, curators, and whoever made an effort to share knowledge and artistic labor, or bothered to carefully engage with these endeavors, thus participating in an expansive dialogue. I try to observe what is suppressed or erased – though I can only account for aspects of which I am conscious, while I am undoubtedly blind to others.

A review is an opinion shared publicly with peers, which, along with other reviews, creates a discourse around specific works or exhibitions and becomes part of their legacy. The strength of the genre lies in its permissive openness to intellectual inquiry as well as personal introspection. I do not see the purpose of merely descriptive reviews, or worse, of just praise. At the most basic register, I feel obliged to share why an exhibition moved me, why it deserves further commentary – thus generating an exchange that transcends the oppressive confines of the white cube, or the specialization of art connoisseurs. A review, for me, has little to do with pretentious art criticism, as though critics are authorities who determine taste, status, and value. A review is an affirmation of accountability, of asserting that what we do, as an art community, matters.

This is where a review means a willingness to be vulnerable, and to force oneself to share unequivocal viewpoints about a particular subject, at a time when litigation enthusiasts and social media trolls dominate the public sphere. It matters when my opinion becomes part of a constellation of ideas that might lead to more meaningful, and critical, future exhibitions and writing, or to raising awareness about typically overlooked aspects of our overlapping yet apparently insular worlds. This vulnerability entails admitting that, for some of us, there is no separation between the personal and political, between art and life. Compartmentalization is a luxury we cannot afford: candid confrontation and debate are crucial for resisting – and existing.

Taking a position matters, especially when it comes to video. While montage may tackle helplessly entangled subjects, this is also a medium that eludes being pinned down, or frozen into a fixed form. Indeed, the constantly shifting medium itself subverts this whole exhibition and exposes the folly of trying to present more than a few dense videos at the same time. Walking through this show is exhausting and ultimately frustrating, as we only get to see fleeting glimpses that slip through one’s fingers as quickly as they are seen.

Being precise – in this case, calling out an exhibition for making exclusions that are uncomfortably aligned with the interests of US empire – matters. As much as I appreciated this show, “Signals” sends mixed signals and makes claims beyond what it delivers, beyond the reality of our world. Well, at least my world.

“Signals: How Video Transformed the World,” Museum of Modern Art, New York, March 5–July 8, 2023.

Amin Alsaden is a curator, educator, and scholar whose work focuses on transnational solidarities and exchanges across cultural boundaries. His research explores the history and theory of modern and contemporary art and architecture globally, with specific expertise in the Arab-Muslim world and its diasporas. He is preparing a book, based on his doctoral dissertation completed at Harvard University, about the art and architectural liaisons that shaped the modernism of post–World War II Baghdad.

Image credit: © Museum of Modern Art, New York, photos Robert Gerhardt