IMPORTUNATE FEMINISM Caroline Lillian Schopp on “Ophelia’s Got Talent” by Florentina Holzinger

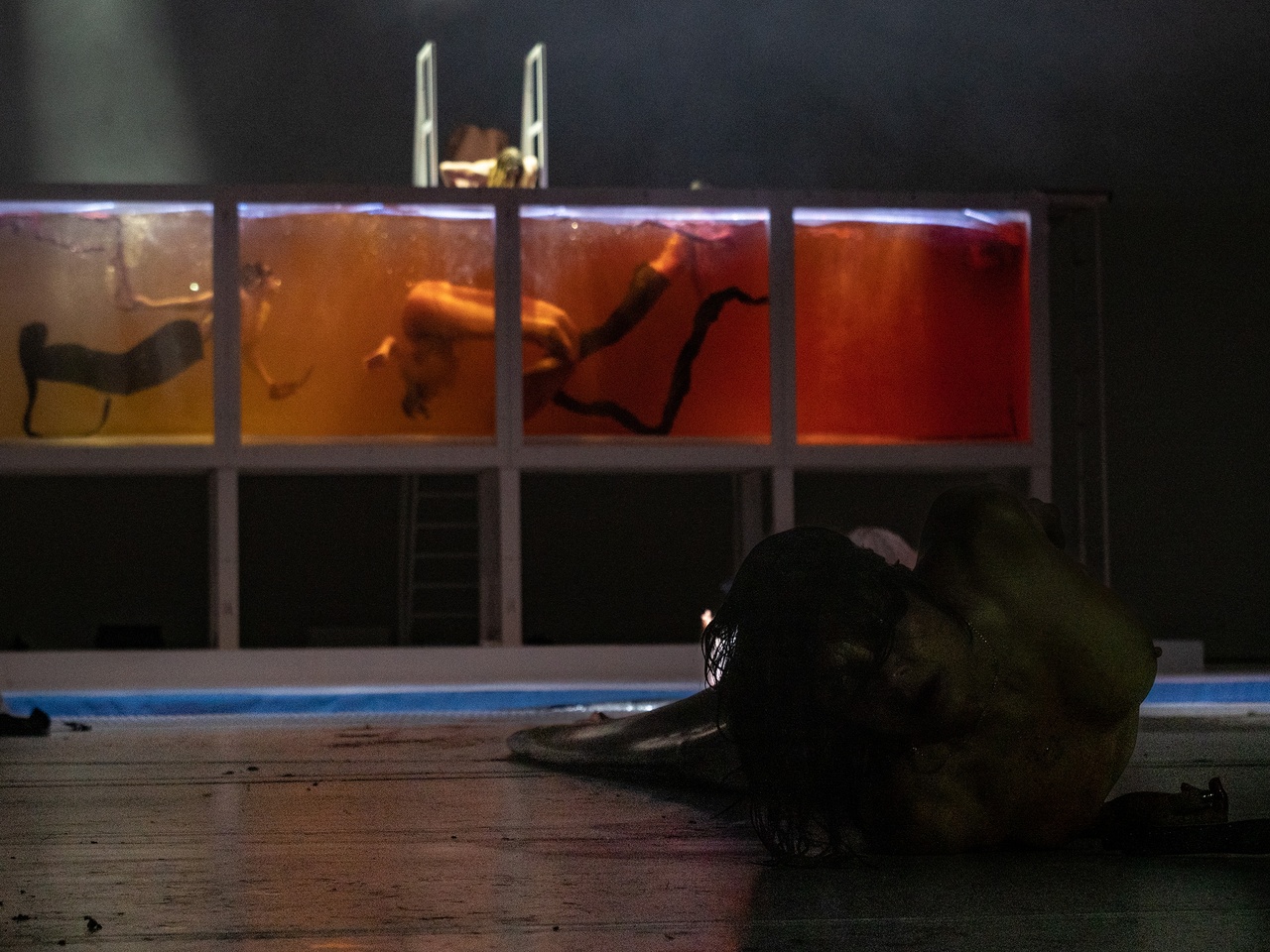

“Florentina Holzinger: Ophelia’s Got Talent,” Volksbühne am Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz, Berlin, 2023, stage photo

About midway through Ophelia’s Got Talent, Inga Busch asks Florentina Holzinger if she has ever played Ophelia. “Not really,” answers Holzinger, deadpan. “It’s such a great role for auditions!” responds Busch enthusiastically. She proceeds to recite from act 4, scene 7 of Hamlet, where Gertrude describes Ophelia’s drowning to Laertes, indulging the way in which this purple passage interweaves femininity, water, beauty, and death. [1] Ophelia herself does not, of course, appear in this scene in Shakespeare’s text, but Holzinger performs Busch’s recitation. As Busch describes the wildflowers in Ophelia’s “fantastic garlands” and how “there is a willow grows askant the brook,” Holzinger clambers sportingly up a vertical staging ladder. At “an envious sliver broke,” Holzinger, in complete control, lets herself fall, thudding inelegantly down the rungs. Aghast, Busch proceeds to coach her on how to land more gracefully “in the weeping brook,” an impressive multi-laned swimming pool embedded in the main stage of the Volksbühne Berlin, in which other performers are swimming lengths and floating. In response, Holzinger throws herself over the water, belly flopping into the pool and splashing about exuberantly. Feigning frustration with Holzinger’s failure to conform to the script of Ophelia’s “mermaid-like” yet in the end “muddy” death, Busch instructs, “No, no, Florentina, don’t fight it so much,” observing with amazement, “She is hartnäckig” (I will return to this phrase). Busch tries to reposition Holzinger’s body to resemble “that famous oil painting” – no doubt a reference to the pre-Raphaelite John Everett Millais’s Ophelia (1851–52) – while encouraging her to sex it up and project a more positive attitude: “I want to see your breasts. Lie still. Be happy.” With Holzinger finally floating on her back, impassive and wide-eyed, Busch concludes: “She is beautiful.”

Ophelia’s Got Talent stridently rehearses the practice of feminist criticism that Elaine Showalter, already in 1985 (the year before Holzinger was born), described as telling Ophelia’s story: not by finding her “true” voice but by examining the history of her representation. As Showalter memorably demonstrated, the iconography of Ophelia binds together “female insanity and female sexuality” in ways that perniciously “infiltrate reality.” [2] Ophelia’s Got Talent gives the lie to any notion that this bond has been undone. At the same time that the performance asks, impatiently, “How now, Ophelia – again?!” – it commits, albeit in a dramatically different form, to Showalter’s project. Holzinger and an ensemble of twelve women performers – Busch, Melody Alia, Saioa Alvarez Ruiz, Renée Copraij, Sophie Duncan, Fibi Eyewalker, Paige A. Flash, Annina Machaz, Xana Novais, Netti Nüganen, Urška Preis, Zora Schemm – stage a spoof TV talent show connecting the iconography of Ophelia to a broader field of cultural production. What does it take to perform the role of Ophelia today? What kind of feminist practice would bother to do so? And what talents are required to achieve Ophelia’s icon-like recognition? In trying to answer these questions, Ophelia’s Got Talent offers bracing viewing.

“She is hartnäckig,” says Busch, tongue-in-cheek. Translated in the surtitles for Ophelia’s Got Talent as “obstinate,” I propose to translate hartnäckig with the obsolete term that is in fact coupled with the figure of Ophelia throughout Hamlet: importunate. This term captures the anachronism, frustration, and persistence of the feminist training practiced in Ophelia’s Got Talent.

In Hamlet, Ophelia is presented as both importuned and importunate. In act 1, scene 3, speaking of Hamlet, she tells her father, Polonius:

“Florentina Holzinger: Ophelia’s Got Talent,” Volksbühne am Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz, Berlin, 2023, stage photo

An incident following the May 14, 2023 performance, in a “discussion” with the public hosted by the Berliner Festspiele, gets to the crux of the matter. A white-haired gentleman in the front row poses the first question. Fixated on a scene in which Novais pierces her cheek with a fishhook and paces vigorously around the stage while holding herself, having hooked herself, like a fish, he asks (I paraphrase): Was it real? With a weary smile, Holzinger confirms that the whole performance is “real with a grain of salt” – we are in a theater, after all. But if it is real, he persists, then why would a young woman do such a thing freiwillig, of her own free will? Novais, with good humor, interjects to say that such acts are part of her artistic work, a practice of freedom. But the insinuation is already in the air: he does not believe that a woman could possibly do violence to herself if she were of sound body and mind. Get thee to a nunnery. Importunate feminism names this historical condition in which we are mired, in which – despite the obstinate and admirable efforts of feminist critical practice – these questions are pointedly directed at women performers. And importunate feminism names the incredulous yet enthusiastic persistence of Holzinger and co.’s performance in Ophelia’s Got Talent, which responds, again and again, to such intractable importunities. I admire Holzinger and her collaborators’ tenacity – and frankly I am grateful that they take such obvious pleasure in it.

Holzinger’s provocative combination of dance-theater, body art, stunting, and freakshow spectacle runs roughshod through the theatrical and art historical representation of women, launching often indiscriminate, humorous, and deeply moving critiques of the dependence of conventional “high” aesthetic forms and artistic practices on violence and misogyny. But instead of criticizing or condemning art for aestheticizing the violence it conceals, Holzinger doubles down. Ophelia’s Got Talent makes the violence that goes into art explicit. The performance is relentless in the face of recalcitrant misogyny, barbed but with humor, careful without moralizing. Ophelia’s talents are presented in scenes of breathtaking discipline and dexterity – aerial pole dance and acrobatics, sword swallowing, synchronized swimming, and whole-ensemble tap- clap- and high-kick dancing, the force of which shakes the theater – as well as in personal narrative accounts of trauma, sexual violence, and institutional violence, in the patient performance of a gynecological exam, a self-piercing, and a tattooing, all played by Holzinger’s diverse and differently abled cast – all of whom, I should at least mention, perform more or less naked the entire time.

Holzinger’s work has occasioned large trigger-warnings on theater programs. The Volksbühne warns of self-harm, blood, needles, stroboscopic light, and “the explicit representation or description of physical or sexualized violence,” recommending a minimum age of 18 years for attendees (despite the fact that children as young as six perform in it, rehearsing a role as historically trite as Ophelia’s – “the future”). Some of this framing is necessary. Yet what Ophelia’s Got Talent is about has less to do with the authenticity of its most graphic scenes and more with how these, too, belong to the iconography of Ophelia, which has become part and parcel of what Holzinger, playing herself, refers to in a monologue as a culture of “therapeutic rape.” [6] Holzinger lists Millais, the pre-Raphaelites, French Symbolism, European Art Nouveau, Rimbaud, Homer, and Ovid as just some of this culture’s artistic preconditions. She then recounts how, when she was about ten years old, she stopped eating and started drinking excessive amounts of water to disguise her anorexia. She was subsequently hospitalized in Vienna and force-fed through a nasogastric tube. What would it look like and how would it feel to perform these importunities on one’s own terms, as a kind of talent?

The entire cast puts this technique to use in an arresting final scene reminiscent of the fountain in the central panel of Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights (1490–1500). All 13 performers assemble in symmetry in and around the swimming pool. With various kinds of hoses, they spray water in luminous crisscrossing arcs while adopting an array of bent-over and unbecomingly inclined postures. Novais and Eyewalker, leaning gently against each other at the center of this touching fountain, thread clear nasogastric tubing through their nostrils, down their throats, and out of their mouths so that the streams of water arcing over their bodies pass through them, penetrate them. The arcs turn red. These waters are muddy, baited. Is this a beautiful scene of violence, a violent scene of beauty? The absence of an unequivocal answer is the importunity of Holzinger’s aesthetic.

Florentina Holzinger, Ophelia’s Got Talent, Volksbühne am Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz, Berlin, premiered on September 15, 2022 and selected by Berliner Festspiele for the Theatertreffen 2023, performed May 13 and 14, 2023 at the Volksbühne.

Caroline Lillian Schopp is an assistant professor of modern and contemporary art at Johns Hopkins University. Her first book, In-Action: Viennese Actionism and the Passivities of Performance Art, is under contract with the University of Chicago Press. Currently, she is working on a project devoted to feminist objections to Duchamp and Picasso in the art history of the 1960s and 1970s.

Image credit: Photos © Nicole Marianna Wytyczak

Notes

| [1] | Holzinger and Busch speak in German in this scene; I loosely translate it here, not following the English surtitles projected above the stage. To translate Busch’s German recitation of Shakespeare, I cite Hamlet, rev. ed., Ann Thompson and Neil Taylor, Arden Shakespeare, 3rd ser. (London: Bloomsbury, 2020). See MIT Shakespeare for an earlier edition online. |

| [2] | Elaine Showalter, “Representing Ophelia: Women, Madness, and the Responsibilities of Feminist Criticism,” in Shakespeare and the Question of Theory, ed. Patricia Parker and Geoffrey H. Hartman (New York: Routledge, 1985), 79, 86, respectively. |

| [3] | Busch is likely using Holger M. Klein’s translation: “Sie ist hartnäckig, ja ganz von Sinnen / man kann nicht anders, als ihren Zustand bedauern” (Stuttgart: Reclam, 1985). |

| [4] | Schlegel’s translation, first published in 1798, is available online through Projekt Gutenberg. |

| [5] | See Showalter, “Representing Ophelia,” especially 85–87. |

| [6] | See Jemma Tosh, The Body and Consent in Psychology, Psychiatry, and Medicine: A Therapeutic Rape Culture (London: Routledge, 2019). |