THE WORLD COULD BE ANYTHING Matthew Cheale on Ridykeulous at Nottingham Contemporary

Charles Atlas, “Turning Portraits + Guest,” 2020/23

In Virginie Despentes’s foreword to Paul B. Preciado’s An Apartment on Uranus, the writer speaks of transformative, transitional space and identity and the ways in which they can open up to you, “where you can become something entirely different from what you had been allowed to imagine.” [1] These ideas of resisting closure, the straitjacketing effects of institutionalization, to remain in the process of ambiguous becoming, manifest themselves in numerous ways as the exhibition “Ridykes’ Cavern of Fine Inverted Wines and Deviant Videos” at Nottingham Contemporary seeks, as the press materials claim, to critically intervene in the age of “capitalist spectacle” that is so closely interested in what we do with our identities, our lives, and our bodies. The show appears both self-consciously aware of its attempts “to critique the art world” and anxious to deflect “the secondary positioning of LGBTQ+ art and artists as ‘alternative.’” [2]

Curated with ingenuity and imagination by Ridykeulous, a curatorial collective founded by Nicole Eisenman and A. L. Steiner (and joined here by honorary dyke Sam Roeck), in collaboration with Nottingham Contemporary’s chief curator Nicole Yip, “Ridykes’ Cavern of Fine Inverted Wines and Deviant Videos” features more than 30 artists engaging with what seem to be three main themes: humor, participation, and queerness. Conceived of in 2005, Eisenman and Steiner’s vision for the initiative was to shift the focus of art and the art world away from its alleged “heteronormativity” toward highlighting the strength, power, and humor of feminine, transgender, and nonbinary subjects, and ultimately, to curate exhibitions of international significance around queer and feminist art. The aim of queering – or frustrating, as Steiner has put it – the art world involves critically engaging with multifarious forms of contemporary art to explore the ways in which meaning, and identity, is (re)produced. [3] The works exhibited at Nottingham Contemporary are mostly made after 2010 and, given the emphasis on video installations, the show unfolds around a number of larger works displayed across several galleries.

Klara Lidén’s short, low-tech video work Warm Up: Hermitage State Theatre from 2014 seemed like the perfect early 21st century riposte to the State Hermitage’s professional ballet rehearsal. It is situated in an opulent domestic interior and, counter to the lithe and graceful movements of the ballerinas on display in the warm-up, the way Lidén’s body moves is awkward and rigid and humorously out of joint. She matches the dancers at first, pointing her right leg almost perfectly upwards and outwards, and then gradually she responds badly with her mishaps of performance, as if the film traps the artist in bodily dilemmas because the classic use of suspended time in live ballet not only creates a kind of physical tension but also brackets the codes of femininity as such. This futility of the body reflects the artist’s own failure to occupy any kind of conventional gender assignation. For Lidén, the inability to remain consistent with the other dancers in the film contrasts with the capacity to control the space in which her videos are displayed. In Warm Up, the artist has wrapped the ends of gallery benches with large bundles of recycled cardboard, allowing only one or two people to sit and view the work at a time. These provisional interventions into the gallery space are interesting as morphological analogues to her critique of gallery architecture and its institutions, and perhaps, the obstruction of gender within them.

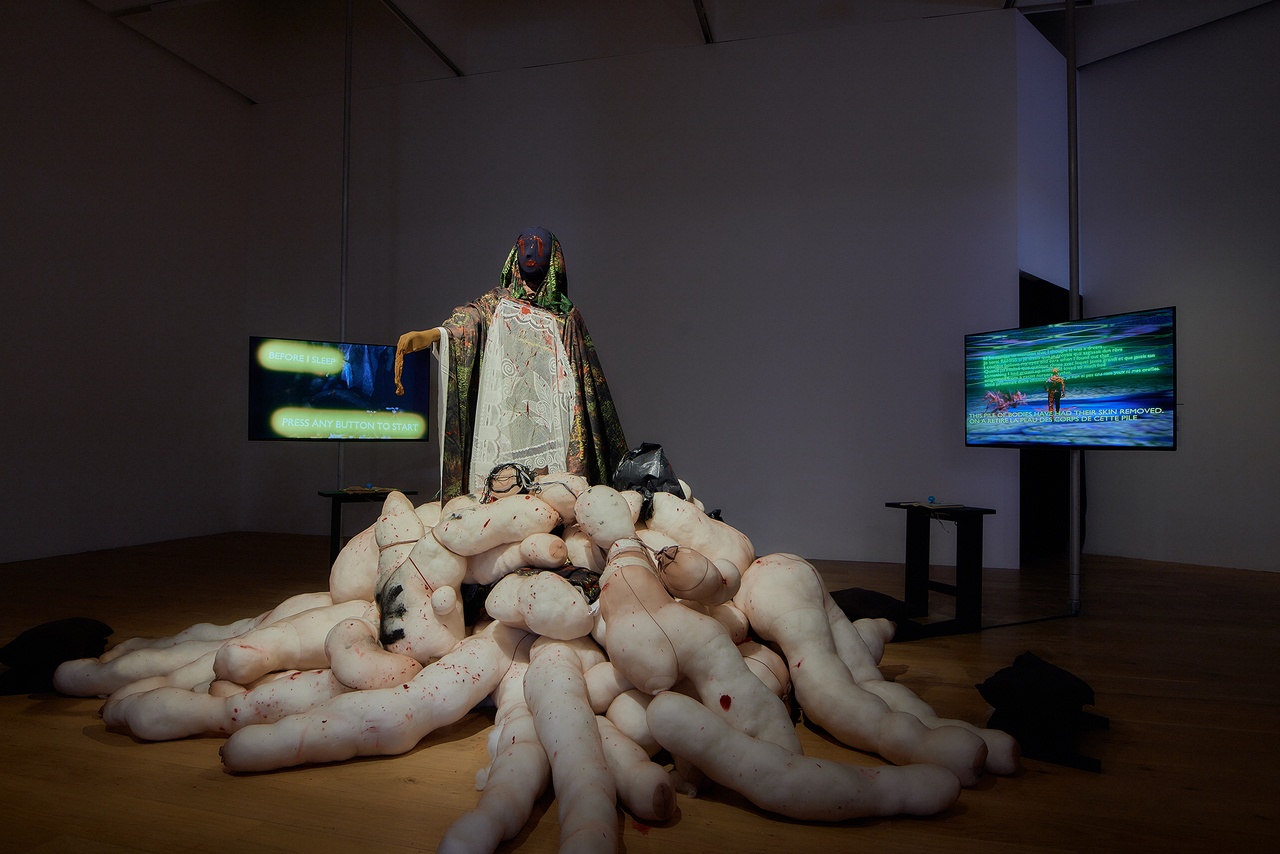

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, “Before There Were None,” 2023

Charles Atlas, another of the more established artists in this exhibition, is represented by the installation Turning Portraits + Guest, which immerses the viewer in a visually dramatic and disorientating atmosphere. Music plays without pause. Repeated sounds and images produce the appearance of another kind of being in the world, one which is performed rather than innate. (You lose your bearings and get wrapped up in the psychedelic abstraction of bodies, provocative outfits, and demure poses.) In a further twist, two of the artist’s previous works, the poignantly intimate Teach (1992/98) – a memorializing of Atlas’s friendship with the nightlife luminary Leigh Bowery – and Turning Portraits (2020), live-edited video portraits filmed during performances of Turning (with [Anohni] and the Johnsons) are combined into a five-channel video. As in much of Atlas’s work, the revelation of the subject in Turning Portraits + Guest is ambiguous: what is uncovered or revealed is also layered and delayed with montaged imagery and digital effects. While it was clearly articulated by the exhibition label that many of the participants in this work were transgender, their identities are rendered all the more elusive. Similarly, the performative aspects of identity are explored by My Barbarian, the all-singing, all-dancing, all-acting performance troupe consisting of Malik Gaines, Jade Gordon, and Alexandro Segade. The appropriation of a host of theatrical tropes for the purposes of performance art is central to their practice. Arranged across the gallery space like props or bodies on a stage are a collection of works comprising two abstractly figural masks made out of papier-mâché newspaper hung on the walls, a sculptural “standalabra” evoking Greek theater, a custom-made curtain, and a video projection titled Maskworkers. The latter showed members of My Barbarian lounging informally on a platform, wearing an ensemble of elegant, colorful masks and periodically parodying movements related to the masked performance of their work Broke People’s Baroque Peoples’ Theater (2012). The masks open up a dissonance between presence and absence: the performers’ physiognomy is hidden behind the masks and not the same as the one being performed, which itself demonstrates the groundless ambiguity of identity. This is toyed with further by virtue of the papier-mâché and “standalabra” that substitute the bodies of the performers. Other works rely on the spectator’s direct participation, raising questions of what it means to be located in a particular place and the material effects of human influence. In Before There Were None (2023) Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley’s sculptures take on the appearance of an ominous specter standing atop a pile of swollen fleshy forms that were made to look like limbs, unnerving if flimsy when shorn from the context of Agatha Christie’s 1939 novel And Then There Were None – a reference claimed by the artist (Christie originally published the book with a racist title, and the plot unfolds around the death, one-by-one, of its ten characters). Brathwaite-Shirley’s work also involves video game elements, offering joysticks to be played with and pixelated graphics on screens, which demonstrate the artist’s ongoing research into the early history of gaming as an art form and how, using this technology, we can seek to archive trans Black experience to reimagine those that have been oppressed by society. Though designed to incorporate the increasing overlap between digital and physical realities, these interactive details often felt jarring, dampening rather than exaggerating the haunting sculptural forms that surround the viewer.

A.K. Burns, “What Is Perverse is Liquid (NS 0000),” 2023

Some of the most beguiling and eerie works were those riffing on and deeply engaged with ideas of political transformation and protest. Filmed mostly in Puerto Rico, Beatriz Santiago Muñoz’s installation is one of the longest video works exhibited. Like Brathwaite-Shirley’s work, it takes its cue from a piece of literature: Oriana (2022) references Les Guérillères, a 1969 novel by Monique Wittig about a band of feminist militants, their escape from a long legacy of patriarchy, and of survival and invention following a violent war of the sexes. In an adjacent gallery space, A.K. Burns presents What Is Perverse Is Liquid (NS 0000), the final instalment of a cycle of video installations on ecological fragility called Negative Space (2015–2023), each concerned with a distinct physical system. For What Is Perverse Is Liquid (NS 0000), which focuses on water, the artist has fashioned a display device-cum-sculpture in the middle of the room: a semicircular piece of Perspex becomes a rippling pool of water when mirroring the projected imagery of a wetland marsh on the adjacent wall panel, and sandbags have been arranged like a defensive barrier to emphasize liquid leakage. On the surrounding screens, performers – “acting agents,” as Burns calls them – navigate their environments and develop relationships with both each other and what surrounds them. Burns has described Negative Space as a sci-fi epic, but the metaphorical seepage of the sandbags and visual portholes might be better understood as allowing meaning to flow freely. As Burns once said, “I want you to feel a sensation of being seduced and drawn into a world you do not understand.” [4]

If the show raises possibilities for representational justice and queer visibility, then perhaps the most pressing one is whether any material and structural change is to be expected as a result. As Luce deLire recently warned in relation to the renewed focus on exhibiting trans identities, “it remains to be seen how sustainable these interventions will be.” [5] Taken altogether, “Ridykes’ Cavern of Fine Inverted Wines and Deviant Videos” offers an ambitious if inevitably multifarious model of what future exhibitions can look like within heteropatriarchal culture, proposing curatorial modes of going about this via the ways we receive and respond to works of art, and a sort of guerrilla tactics. Like Preciado’s ability “to think elsewhere, in the interstices, to want to live on Uranus,” [6] Ridykeulous asks you to join them in their bizarro world of humor and transformation: “The world could be anything. Just lick whatever toad is left, you’ll see.” [7]

“Ridykeulous: Ridykes’ Cavern of Fine Inverted Wines and Deviant Videos,” Nottingham Contemporary, September 23, 2023–January 7, 2024.

Matthew Cheale is a London-based writer, editor, and art historian.

Image credit: Courtesy of Nottingham Contemporary, photos Adrian Vitelleschi Cook

Notes

| [1] | Paul B. Preciado, An Apartment on Uranus, trans. Charlotte Mandell (London: Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2021), 19. |

| [2] | “Ridykes’ Cavern of Fine Inverted Wines and Deviant Videos,” press release, Nottingham Contemporary. |

| [3] | In 2016, A. L. Steiner’s artist statement proclaims “to dismantle homo economicus in a post-semantic omnicidal world.” See “A. L. Steiner,”. |

| [4] | A.K. Burns quoted in Louisa Elderton, “A.K. Burns: Julia Stoschek Foundation Düsseldorf,” Reviews, Artforum 58, no. 7 (March 2020). |

| [5] | Luce deLire: “Beyond Representational Justice,” Texte zur Kunst 129 (March 2023), www.textezurkunst.de/en/129/luce-delire-beyond-representational-justice. |

| [6] | Preciado, An Apartment on Uranus, 17. Italics in original. |

| [7] | Ridykeulous, “Ridykeulous on the New World Disorder,” Slant, Artforum, January 28, 2017. |