THE SYMPTOM AS PERFORMANCE Emily Wells on Charcotian Psychiatry and Pathologies in Dance and Art

Loïe Fuller dancing, 1902

It must have been apparent to Jean-Martin Charcot, from the moment Augustine arrived in the hysteria ward at the Salpêtrière, that she would be his next medical celebrity. She is all symptom, or the idea of the symptom. She is a beautiful object of desire, a victim of misogyny, a Bartleby, a mascot, whatever you would like her to be. There isn’t even historical consensus about what she was called. In 19th-century materials, she is never called Augustine; she is either X.L., L., X., Gl., Louise, Louise Gl., Louise Gleiz., Louise Glaiz., or simply G. The first mention of “Augustine” I have found is in the second volume of the Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière (1877), a landmark publication of medical photography that sought to present photographs as pure signs of a depicted patient’s illness, clinical features divested of any interiority – it cannot be overemphasized that everything we might find beautiful or interesting in the images, all of the inflections of Augustine’s bodymind, exist despite the manner in which they were captured and recorded. The first edition includes no captions or case histories to describe the photographs, only section titles that categorize the patients as hysterics, epileptics, or other/miscellaneous. After the second volume of the photographs from the Salpêtrière was released, a reviewer from the British Medical Journal griped in 1879, We must say that we regret that a work of such great scientific interest should be to English readers rendered somewhat unsavoury reading by the introduction of long pages of the obscene ravings of delirious hysterical girls, and descriptions of events in their sexual history. ... [I]f described in the loose words of the patient when delirious and completely under the influence of a hystero-epileptic attack, such description may be interesting to the inquisitive student of diseased and degraded human nature, but is actually, in the words of the law-courts, “matter unfit for publication.”

My study of Augustine is often enveloped in wordless color and texture, a thick brain fog. Whether or not she was conscious, or had intent, or got to see her images, it is Augustine’s relationship to her own body and her own image that holds my captivation. I am skeptical of the purported cultural value in allowing oneself to be visually documented; when I observe the images taken of me in my modeling years, I see not feminist tools of resistance, but a woman ambushed by economic necessity into an unsavory state of self-corroboration. In those photos, I am cold, bereft, absent; aligned with the aesthetic of the time but also characteristically withholding, austere.

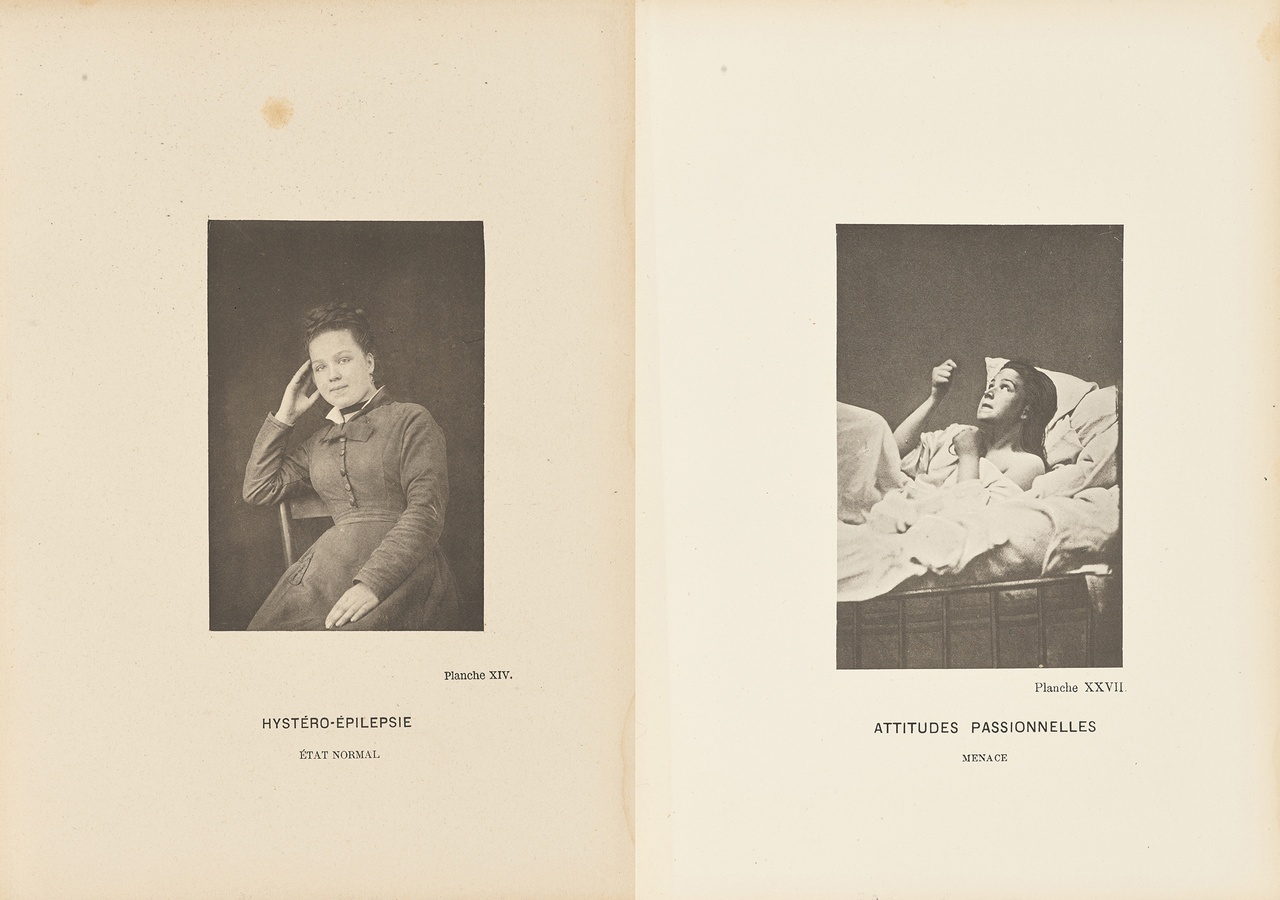

At the Salpêtrière, a hysteric’s symptoms were recognized only when they presented in visual form. In Augustine’s photographs – I have come to think of them as fundamentally hers – Augustine expresses one big emotion at a time. Joy. Confusion. Pain. Fear. The most neutral is the first photo, taken of her after her arrival, when she was about 14. “Normal State” features her sitting calmly, upright, in civilian clothes, comfortably posed in front of the camera, her gaze meeting it directly. Her cheekbones are high, her features symmetrical, and she is unashamed and wearing a slight smile. There is nothing of hysteria in the image. Though 18 pages of notes follow, covering 21 months of her life and many more dramatic gestures, tics, and grimaces – allegedly in correlation with corporeal pathologies – next to nothing can be learned about her life from the volumes documenting her symptoms. Nevertheless, Paul Regnard, who took the medical photographs, knew something about capturing a woman. Augustine is always perfectly lit, well framed, and you can tell she has color in her face. She is never swallowed up by the light of the camera and must have practiced holding the passionate poses for a great deal of time. Despite having been subjected to medical tests in which doctors “pulled her hair, tickled, punched, and pricked her; they examined the mucous membranes of her eyelids, nostrils, mouth, tongue, and vulva ... tested her hearing, vision, taste, and sense of smell,” in the photos, she always appears untouched, distant, possessed only by herself and the singular emotion overtaking her, labeled clearly under each photo. It is never apparent what the depicted medical symptom is, other than a feeling.

Paul-Marie-Léon Regnard, “Augustine Gleizes, Normal State” and “Augustine Gleizes, Menace,” 1878

Stéphane Mallarmé, who watched an astounding amount of ballet and theater despite finding most of it unbearably banal, attended the theater in search of an elusive idée, some invisible divine presence transcending whatever was happening on the stage, something free of representation and shallow spectacle. His poet’s eye, as he describes it in the prose poem “Un spectacle interrompu,” allows the poet to see more than what is visible, prioritizing intellectual or imaginative elements – insight rather than sight. It makes sense, then, that he was more moved by the abstract, theatrically lit dances of Loie Fuller than any romantic story ballet: “Here brought to Ballet is the atmosphere, or nothing,” [1] the “nothing” here being the elusive divine spirit of man, free from representation. Transcendent nothingness may have been Mallarmé’s object of admiration, but in her famous Serpentine Dance, Fuller was likely imitating hysterics. In her memoir, Fifteen Years of a Dancer’s Life (1908), she describes the takeoff of her career after performing the dance, which was based on a medical parody play, Quack, M.D. (1891), noting that “hypnotism at that moment was very much to the fore in New York.” The play features a scene of “hypnotic suggestion” from Dr. Quack: “I endeavoured to make myself as light as possible, in order to give the impression of a fluttering figure obedient to the doctor’s orders. He raised his arms. I raised mine. Under the influence of suggestion, entranced – so, at least, it looked – with my gaze held by his, I followed his every motion.” [2]

In Dance Pathologies (1998), cultural historian and performance theorist Felicia McCarren articulates early modern dances like Fuller’s as a response to the tradition of dance’s resemblance to hysteric poses. She writes, “Mallarmé’s dance texts on Loie Fuller record a shift away from the spectacular and toward the specular as Fuller’s dance offers its spectators not simply sight, but insight.” [3] On Fuller’s subsequent dances, which incorporated the theatrical lighting for which she came to be known, “Mallarmé describes [her] performing persona as facilitated by the ‘absolute gaze’ created by electric light, a gaze that can be identified with what Michel Foucault refers to as the ‘absolute gaze’ of the nineteenth-century physician newly armed with instruments.” [4] The dancer under the absolute gaze is hypnotized, electrified, but the distinction of Fuller, Mallarmé says, is that she is self-hypnotized; her electric lighting is of her own creation. Her “use of the clinical apparatus used to diagnose and treat hysteria,” McCarren says, “functions as a critique of Charcotian psychology, and reveals to what extent technological agency imposes a hierarchy of well and ill.” [5]

Loïe Fuller dancing with her veil, 1897

During my childhood spent in ballet, suffering from a rare, undiagnosed autoimmune disease, my illness was treated as a metaphor. I simply felt too much. To civilians – the word some of us used to refer to non-dancers – I was a young woman who spoke about her body as though it were her essential stake in the world, an entity capable of moods entirely separate from her own. I commiserated with the other dancers on our constant fatigue, on the endless ministrations of the body, our worries so out of sync with those of other young people. We were living at an accelerated pace in which each year counted for more than an ordinary fraction of life. But at some point, ballet became even more difficult. People described ballet as painful all the time, but I wondered if this was what it felt like for the other girls, if the simplest tendu sent searing pain through not only their pointed feet, but also their entire bodies. I wondered if they too had learned to angle their faces precisely during a grand jeté in such a way as to minimize any wincing. I assumed that this was what worthwhile endeavors felt like, that the ability to perform required suffering and sacrifice and ruin. Pain exists in the mind, and I knew I could be happy if I focused on a purely physical selfhood. For a while, no one noticed how much harder things were getting for me, because I could appear to keep up, suffering the consequences later, alone. I got thinner; I was complimented. My hair thinned; I cut it. I got shin splints; I developed a taste for stimulants.

A dance teacher once described his own retirement and the bodily sensation of no longer being able to dance familiar movements as a loss of muscular sanity. It was a term he might have read – though I doubt it – in an 1890 entry from the diary of Alice James (sister of William and Henry): “Owing to some physical weakness, excess of nervous susceptibility, the moral power passes, as it were for a moment, and refuses to maintain muscular sanity, worn out with the strain of its constabulary functions ... it used to seem to me that the only difference between me and the insane was that I had not only all the horrors and suffering of insanity but the duties of doctor, nurse, and straight-jacket imposed upon me, too.

In this same entry, Alice references a paper by her brother William, titled “The Hidden Self,” in which he writes that the hysteric “abandons part of her consciousness because she is too weak nervously to hold it all together.” William believed the theories emerging out of the Salpêtrière that the abandoned part of the hysteric’s consciousness “may solidify into a secondary or subconscious self.” [6] Alice seems to have believed in this conception of hysteria, too, but often, the way she describes the cognitive aspects of her condition feel more akin to the sluggish “brain fog” that so often accompanies chronic illness, including mine: “conscious and continuous cerebration is an impossible exercise and from just behind the eyes my head feels like a dense jungle into which no ray of light has ever penetrated.” Alice’s mother believed her to be suffering from “a genuine case of hysteria.” [7] As my symptoms continued to be interpreted as a lack of “nervous togetherness,” I began to wonder if I might be, too.

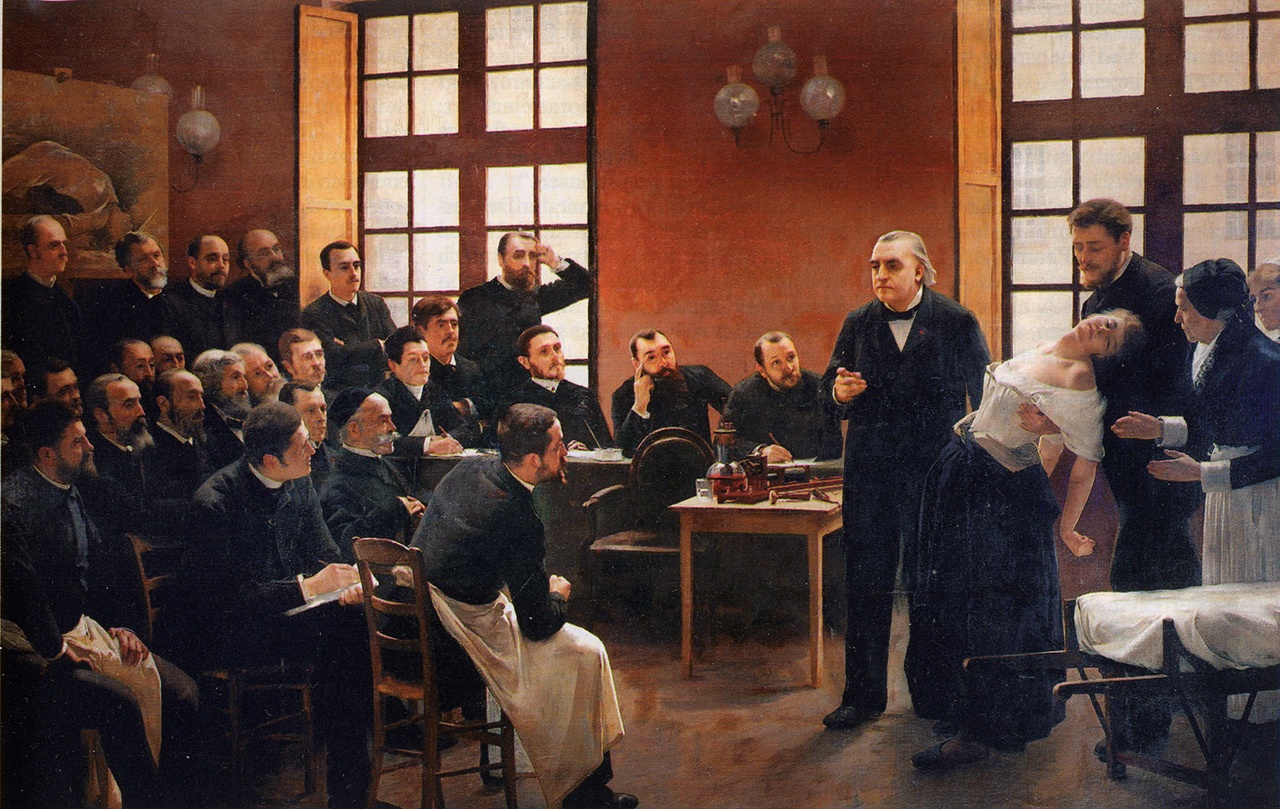

André Brouillet, “Une leçon du Dr. Charcot à la Salpétrière,” date unknown

Charcot was almost completely uninterested in his patients’ words, even when they were reenacting traumatic, often sexual episodes – Augustine’s visions included “rape, blood, more fires, terrors, and hatred of men”; scenes from novels she had read; and, according to Désiré-Magloire Bourneville, a neurologist working at the hospital, the hallucination that “when the men around her speak, flames emerge from their mouths.” [8] It is difficult to imagine, given the pointed nature of the hallucinations, but Charcot considered anything said during a hysteric attack to be “vocalization, not communication, a clinical feature that helped to differentiate hysteria from diseases it resembled, such as epilepsy.” During one of his lectures, he presented to his viewers a hysteric in the midst of an attack. She called out, “Mama, I’m scared,” after which, Charcot remarked to his audience, “You see how hysterics scream. One could say that is a lot of noise about nothing. Epilepsy is more serious and much more silent.” [9] But Augustine was a talkative girl. During another demonstration, Charcot induced a contraction of her tongue and larynx muscles, leaving her mute for six days.

While Charcot sought to identify an organic biological illness causing the hysterics’ symptoms, Bourneville was more inclined toward considering the psychological context of the patients. He paid attention to the consistency of trauma in the histories of the women of the Salpêtrière years before Sigmund Freud developed methods to force them to relive it, repeatedly, in the hope that something useful might emerge. Bourneville justified including a great deal of information about each patient’s life, “so that our readers can clearly appreciate [...] the different phases of the delirium phase of the attack.” It was Bourneville’s idea to photograph the hysteria patients in Charcot’s ward, to allow them to speak through, or be lost in, the language of images.

Why do I retain attachment to such a famously problematic word, hysteria, when it invites metaphor and messy historical analogy? According to literature and culture scholar Rachel Mesch, the contemporary feminist answer to the question of hysteria can be summarized through two broad directions: the first considers the hysteria diagnosis to have been a medical silencing of women who challenged the social organization of society. The second takes a psychoanalytic perspective, seeing hysteria as a form of female resistance. In everyday use, hysteria still means “uncontrolled or dramatic emotional display,” but in the Lacanian psychoanalysis clinic, the hysteric holds revolutionary potential. It was Jacques Lacan who, in his four discourses, set up the hysteric’s discourse as that which can overturn fixity and uncover new lines of inquiry. In a Lacanian clinic, a diagnosis of hysteric is far from an affront: as the psychoanalyst Anouchka Grose puts it, “Dissatisfaction is the motor for desire, and desire drives existence. Hysterics specialise at using dissatisfaction to keep desire spinning, acting against atrophy and ossification. Far from trying to get them to stop fussing and get back in line, one might encourage them to take their questioning further, to use it in their lives and work, and to even attempt to enjoy it.” [10] If, as Lacan said, the only distinction between humans and animals is that we are afraid of our shit, the hysteric, unafraid of paradox or truth or shit, can be seen as a seeker, someone who uses her discomforts and dissatisfactions as means to interrogate the Other. The hysteric’s dissatisfaction keeps desire spinning – a preferable interpretation to the body-as-contradiction being problematized.

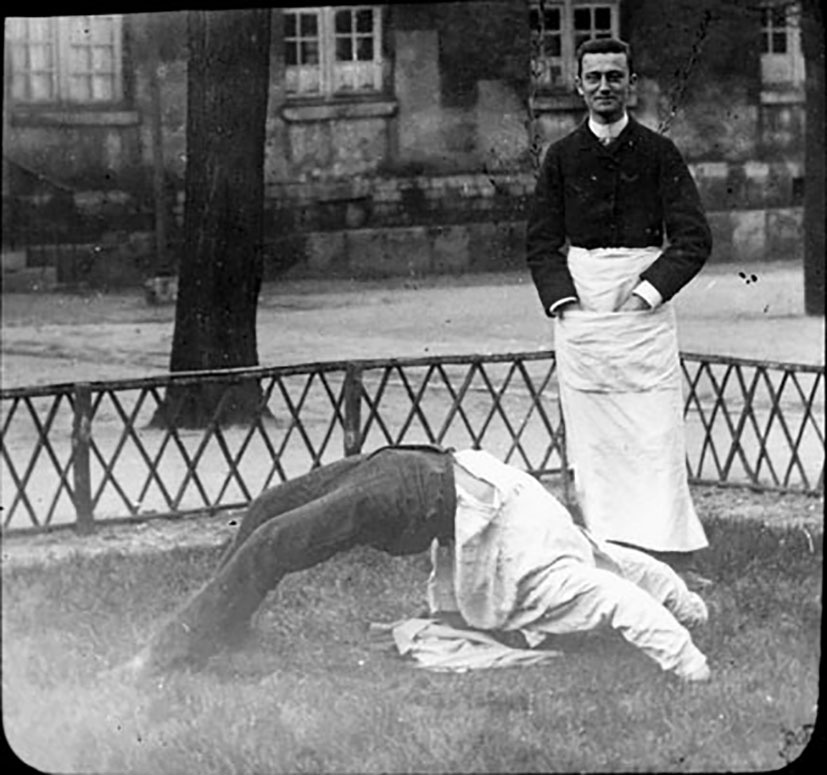

Albert Londe, “Attaque d'hystérie chez homme,” 1885

One need not endorse Freud’s theory of hysteria as unconscious ideas or desire that manifests itself in symptoms in order to use it toward an idea’s shape. After reading Freud enthusiastically, the artist Louise Bourgeois entered analysis in 1952, at the age of 40. She was experiencing a cluster of symptoms (insomnia, depression, fits of anger, agoraphobia, dizziness, sore throats, nausea) and dichotomous digestive issues, many consistent with those previously attributed to hysteria. The emotional turmoil she experienced after the death of her father (“literally cannot live or function / without the protection of a father,” reads a diary entry from 1952) encouraged her to seek treatment. Bourgeois’s work invites psychoanalytic narrative as an entry point, returning again and again to a common family drama: Louise’s father was unfaithful to her invalid mother by sleeping with Louise’s governess, and Louise’s mother tacitly used her daughter to keep an eye on the affair. The story could have been adapted from any number of the case studies in Freud’s and Josef Breuer’s Studies in Hysteria (1895). Bourgeois wrote, “Since the fears of the past were connected with the functions of the body, they reappear through the body. For me, sculpture is the body. My body is my sculpture.” [11] Much of her work seems to replicate Freud’s structure of symptom formation, though Arch of Hysteria (1993) maintains the most explicit dialogue: a hanging figure of a male body cast in bronze is bent backward in a maneuver reminiscent of the arc-de-cercle, a famed pose of the hysteria patients at the Salpêtrière in which the body is arched upward, locked in spasm, with weight only on the head and feet. In neither the case of the patients nor in Bourgeois’s symbolic body is it clear if the body is in pain or pleasure, if it is expressing illness or jouissance – or, if illness, whether it is caused by or reflects the mind. In both cases, the body is frozen, exposed, defenseless, suspended in time.

Emily Wells is a writer living in Los Angeles. A Matter of Appearance, her debut memoir, was published by Seven Stories Press in 2023.

Image credits: 1. public domain, photo Frederick Glasier; 2. public domain, Getty Museum Collection; 3. public domain; 4. public domain, Bibliothèque interuniversitaire de Santé; 5. public domain, Bibliothèque de Toulouse

This essay is an adaptation from A Matter of Appearance, courtesy of Seven Stories Press, 2023.

Notes

| [1] | “Here brought to Ballet is the atmosphere, or nothing”: Stéphane Mallarmé, Oeuvres complètes (Paris: Pléiade, 1945), 313; quoted and translated in Felicia McCarren, Dance Pathologies: Performance, Poetics, Medicine (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1998), 117. |

| [2] | Loie Fuller, Fifteen Years of a Dancer’s Life: With Some Account of Her Distinguished Friends *(London: H. Jenkins Limited, 1913), 31. Originally published in French as *Quinze ans de ma vie (Paris: Félix Juven, 1908). |

| [3] | McCarren, Dance Pathologies, 25. |

| [4] | Ibid., 157. |

| [5] | Ibid., 25. |

| [6] | William James, “The Hidden Self” [1890], Wikisource, n.d., en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Hidden_Self. |

| [7] | Alice James, The Diary of Alice James, ed. Leon Edel (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1964), 148–50. |

| [8] | Georges Didi-Huberman, Invention of Hysteria: Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière, trans. Alisa Hartz (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003), 137. |

| [9] | Asti Hustvedt, Medical Muses: Hysteria in Nineteenth-Century Paris (New York: Norton, 2011), 188–89. |

| [10] | Anouchka Grose, introduction to Hysteria Today, ed. Anouchka Grose (Abingdon: Routledge, 2018), xv–xxxi, here xxx. |

| [11] | Louise Bourgeois, quoted in “Self-expression Is Sacred and Fatal,” in Louise Bourgeois: Designing by Free Fall by Christiane Meyer-Thoss (Zurich: Ink Press, 2016), 228. |