HOW SOON IS THEN?, ANDREW STEFAN WEINER ON “THIS WILL HAVE BEEN” AT THE INSTITUTE OF CONTEMPORARY ART, BOSTON

Donald Moffett, "Call the White House", 1990, Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery

Can we really speak of the 1980s as history? In some sense it seems as if the 80s never stopped, given their seemingly inexhaustible power over young taste-makers, many of whom “remember” the era better than elders who actually lived through it. The uncanny temporality of “the 80s” troubles the tidy categories of decades and generations that much art discourse relies on. So how might it be possible to historicize the art of that moment? This question was thoughtfully and incisively addressed by the recent exhibition “This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s”, curated by Helen Molesworth, the first retrospective on the subject to tour major US museums.[1] Taking as its credo Roland Barthes’ account of photography’s proleptic power – its ability to anticipate future pasts – the show examined how the art of the 80s registered the effects, temporal and otherwise, of new technologies, transformations in political economy, and the AIDS crisis. At its most ambitious, “This Will Have Been” aspired to mimic its subject by initiating relays between aesthetics, affect, and activism, asking viewers to judge the present against former aspirations and desires.

If Molesworth sought to re-periodize the 80s by extending the decade from 1979 to 1992 (the years spanned by the work in the exhibition), her larger aim was to introduce new categorizations. Rather than rehash tired postmodernist formulas like the opposition between appropriation and Neo-Expressionist painting, she organized her survey around four “problem-ideas”: endings, democracy, gender, and desire.[2] These groupings set up provocative juxtapositions of seemingly dissimilar practices – like the acerbic restraint of Rosemarie Trockel against the Dionysian No Wave of Mike Kelley – enabling the show to pursue an ambitious argument about the legacy of the social movements of the 1960s and 70s. Molesworth placed feminism at the center of this history, tracing a dense network linking art, politics, and theory. Feminist art was not exiled to its own separate-but-equal gallery, as so often happens. Rather, it ran through the entire show as both content and concept, with feminism defined in relation to the politics of identity within a mass-mediated public sphere. Given the show’s thematic, non-chronological layout, viewers were asked to grasp feminism as happening everywhere and all the time, an important correction to the strange exclusion of the 1980s from recent surveys of feminist art.[3] From this perspective, the work of Martha Rosler and Jenny Holzer could be seen as bridging the gaps between the video underground, the Pictures scene, ACT UP, and the use of gender and race as “readymades” by artists such as Jimmie Durham. Even more radically, Molesworth claimed that artists like Deborah Bright and Isaac Julien helped make the queer and postcolonial theory of the 1990s possible by producing forms for which concepts did not yet exist.[4]

Deborah Bright, "Dream Girls", 1989-90, Courtesy of the artist

While “This Will Have Been” was in many ways a curatorial tour de force, presenting a fresh, broad, and impassioned account of its subject, one of Molesworth’s greatest successes was letting the art stage its own argument. In some places this meant showing works that problematized the hegemonic recuperation of resistant forms, such as Tony Tasset’s “Button Progression” (1986); in others it entailed provocative juxtapositions, like hanging Robert Mapplethorpe’s photos of nude black men across the gallery from similar images made by the Nigerian-born Rotimi Fani-Kayode. While this pairing acknowledged the racialized fetishism of Mapplethorpe’s portraits, it also marked a sharp contrast between the American’s neoclassicism and Fani-Kayode’s less notorious but far more compelling hybrid of traditional Yoruba iconography with quasi-Surrealist erotic abstraction. Against the melancholic epochalism of Rosalind Krauss’s “post-medium condition”, Molesworth showed works that carefully explored contingent forms of intermediality: Jennifer Bolande’s “White House Drawings” (1982), in which magazine photos of the Reagan White House were repeatedly copied by both hand and camera; or Eugenio Dittborn’s “Airmail Paintings” (1984–ongoing), which located a genuine political urgency in seemingly exhausted forms drawn from mail art and photo-conceptualism.

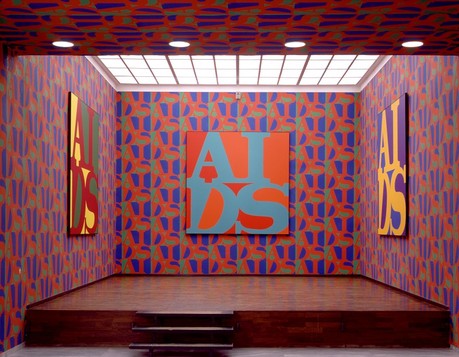

General Idea, "AIDS Wallpaper", 1989, Courtesy of AA Bronson

One emerged from the show feeling both stimulated and moved, if also perplexed by some of its oversights. The largest of these was geographical, with the selection of artists displaying a heavy bias towards the North Atlantic. The vast majority of those shown were American (most based in New York), with Europe represented primarily by blue-chip German painters. Except for a cluster of Latin American artists, the rest of the globe was largely omitted. While such a bias doubtless reflected the profound, long-lasting effect of Cold War geopolitics, which restricted contact between the First, Second, and Third Worlds, Molesworth should have pushed harder to rewrite this history. Her argument would have been broadened by examining less familiar examples of art, desire, and politics – such as the charged modes of performance developed in pre-Tiananmen China by members of the ’85 Movement. The show also could have examined links between socially engaged Western artists and their Soviet bloc counterparts by including works like Allan Sekula’s photo-documentation of the Solidarity movement in Poland. While Molesworth gestured toward Latin America, showing artists like Doris Salcedo and Alfredo Jaar, she missed a chance to explore the less well-known, more transversal models developed by the Border Art Workshop or the Cuban collective Grupo Provisional.

Jeff Koons, "Rabbit", 1986, Collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago

Such selections would have enabled the exhibition to more radically reframe the 80s as an era when other non-synchronous, transnational postmodernisms emerged. Against the dominant art-historical opposition between “critical” (Sherrie Levine) and “symptomatic” (Jeff Koons) postmodernisms, we need a model that accounts for the unevenness of global development – for example, the fact that much neoliberal policy was first tested in Latin America during the 1970s. A more global perspective also could have checked a subtle but still troubling tendency in “This Will Have Been”: nostalgia for the 80s as the last moment when downtown New York seemed like the center of the art world, if not the whole world. At times this bias interfered with the show’s otherwise commendable efforts to track the ascendancy of neoliberalism, whether in debates over tax cuts and so-called “entitlements” or in the culture wars and the AIDS crisis. Practices like those shown by Molesworth, given their sensitivity to mediation, could help us better understand the role of the aesthetic in the privatization of the public sphere – a process that is still ongoing, and which likely informs our sense that the 80s have yet to pass. Like the two clocks in Félix González-Torres’s “Untitled (Perfect Lovers)” (1987-90), which start out synchronized but gradually end up telling different times, the work included in “This Will Have Been” gestures toward a different historical horizon, remaining always a step ahead and yet somehow also just about to happen.

"This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s", Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, November 15, 2012–March 3, 2013

[1] One recent precedent is the 2007 survey “The 80s: A Topology”, co-curated by Ulrich Loocke and Sandra Guimarães for the Serralves Museum in Porto, Portugal.

[2] For more on these thematics, and on the concept of the “problem-idea,” see Helen Molesworth, “This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s,” in: same (ed.), This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s, Chicago 2012, pp. 14–46.

[3] Molesworth criticizes the exclusion of the 1980s in “WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution” and “Global Feminisms” (both 2007); Molesworth, 15.

[4] Molesworth, p. 16.