THE BEST PROPHET IS THE ASSASSIN Stephanie LaCava on Hit Men, Puppeteers, and Holy Forms of Parallel Play

Raphael, “The Sibyls,” c. 1514

Dispense with that arch tone. It’s a killer. Not the good kind. Hardest to swallow when its denial cries answers to questions that don’t have any. Or worse: questions that no one asked. Spy time. Ironic or sincere? All the three-character kinds of agency. CIA, KGB, MI6… FML, KMS. A myth that surveillance reigns. If you’re always detached in spirit, you’re insulated by a scene that isn’t even real.

A few nights ago, there was a talk in New York on Canal Street in the office space of an internet magazine. Real bodies filled the room, and the elevator malfunctioned not once, but twice, when more than four people were inside. On stage, to the right: poet and novelist Kaveh Akbar. To the left: critic and writer Anahid Nersessian. “Originality is overrated,” Nersessian said at some point, meaning it’s okay to nod back and know the past. This is different than the artist signaling she’s smart by someone offstage puppeteering contextualization.

It’s a true critic’s sensitivity that can tell the charlatan from the clown. Provenance is the stuff of research, not practice. Historic reference isn’t clever when knowledge is shallow and the endgame high-profile. Smash yourself with something great, this doesn’t mean you become great too. Nersessian asks for a return to savage critical insight, which is knowing the difference and which differences matter. On the other side, Akbar talks about how the best fiction doesn’t offer tidy moralization, or judgement even. Its pages are meant to show us, after all, as humans. Critics with X-ray eyes and hard opinions are twin flames to fiction writers who offer neither. The critic with a real take equals the novelist showing the world’s lack of one. On high alert, she is hypersensitive to both sibyls and saints.

Books like Kaveh Akbar’s Martyr! (2024), Fernanda Eberstadt’s Bite Your Friends (2024), and Robert Glück’s Margery Kempe (1994) fan out in the background. Martyr! gives way to Eberstadt’s collection of autobiographical stories spliced with Diogenes the Cynic, St. Macrina, Perpetua and Felicitas, Peter Hujar, Henry Darger, Abel Barbin, Michel Foucault, and Pier Paolo Pasolini. There is a through line of Eberstadt’s friendship with downtown performance artist and playwright Stephen Varble, an unconscious re-creation of the dynamic between her late mother Isabel and underground filmmaker Jack Smith.

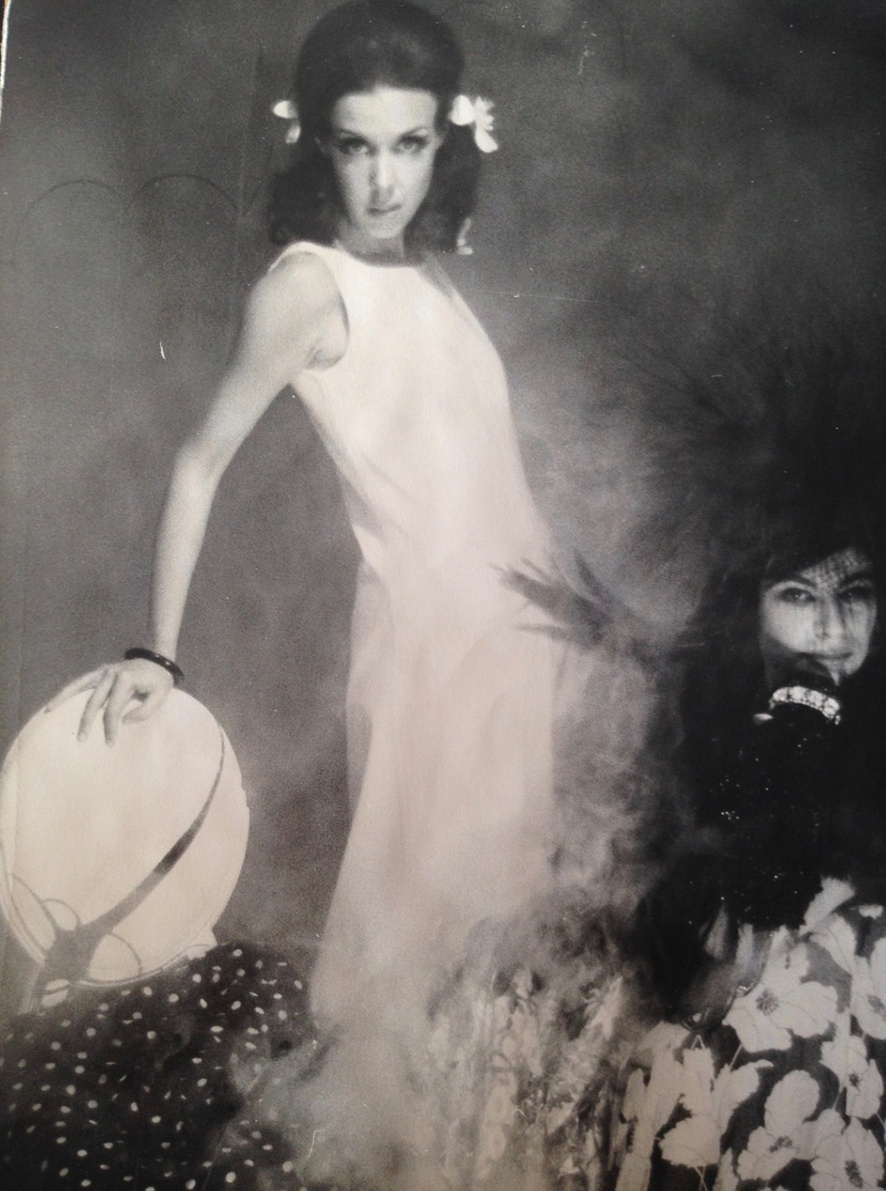

It was Isabel Eberstadt’s Balenciaga dress that Mario Montez wears in Smith’s 1968 film No President, which she also produced. The feature film dances between documentary footage of 1940 electoral candidate Wendell Willkie and a story shot in Smith’s own Greene Street apartment. There are liberal Republicans alongside pirates. No President, like Bite Your Friends and Margery Kempe, deliver real-time anecdotes alongside historic tales. This allows for doubled down complexity, equal parts in both mismatched and mirror images. There’s nothing gratuitous about such pairings with the canonical, no seeking to secure one’s own credibility.

Mario Montez and Isabel Eberstadt on the set of Jack Smith’s film “No President,” 1968

Parallel play only works when it seeks to show the through line of messy humanity. It distracts respective parties from their singular hang-ups. Always, the saint is our sibyl; the modern sibyl our last saint. Pasolini continues to resurface because he is the telegenic poster boy of confusing ideals.

A few nights ago, the Oscars happened in Los Angeles, on the other side of the country. “I’ve managed to write about the movies for a lifetime without ever writing about the Academy Awards. That’s a great source of pride,” Pauline Kael wrote in 1998.

The morning after, armchair Kaels are buzzing, misquoting hot takes on Jonathan Glazer’s best international feature film acceptance speech for The Zone of Interest (2023). Someone’s already tried to claim the Academy tried to censor said clip by refusing to upload it. A counterclaim is posted that may or may not be dubious. Among all the frenzied misinterpretations, equal attention seems to be paid to Jennifer Lawrence wearing vintage Givenchy Haute Couture. It’s the same Josephine-style dress Kate Moss wore on a 1996 runway. The white velvet shamrocks are unnecessary good luck, because all the dies have already been cast. Later that night, another starlet shows up in resurrected finery: Sydney Sweeney in the very white Marilyn Monroe–esque Marc Bouwer that Angelina Jolie wore twenty years ago. All of this is discussed in the same streams as Glazer’s speech. Even the greatest sibyl couldn’t offer a nowadays algorithm to emulate the logic of choosing which old thing wins over another.

There’s a line in Margery Kempe that seems to encapsulate this moment. It’s worth noting that the book tells the story of an English Christian mystic – one of Jesus’s lovers who failed to become a saint, in parallel with Glück’s own real-time romantic obsession: “The best prophet is the assassin.”

Not long ago, Hollywood’s own Quentin Tarantino announced that his tenth film will be his last.

Stephanie LaCava is a novelist and critic. Her first novel, The Superrationals, was published by Semiotext(e) in 2020, while her second, I Fear My Pain Interests You, came out from Verso in 2022. She lives in New York City.

Image credit: 1. Public Domain; 2. Courtesy of Fernanda Eberstadt