THE UNFINISHED BUSINESS OF SENTIMENTALITY Ana Teixeira Pinto on Tarik Kiswanson at carlier | gebauer, Berlin

“Tarik Kiswanson: The Reading Room,” carlier | gebauer, Berlin, 2023–24

Origin stories are a prominent and popular trope that recur in pop culture. Almost all superheroes have one – a traumatic backstory about ravaged worlds, murdered parents, or induced mutations. Some artists also have origin stories that exceed the typical CV. Joseph Beuys notoriously manufactured his messianic creation myth involving flight, a life-changing accident, and his miraculous rescue, which doubles as a form of redemption. Others, like Artemisia Gentileschi, had their own harrowing tales turned into a selling point.

In reviews and press releases dealing with Swedish Palestinian artist Tarik Kiswanson’s work, one origin story keeps recurring: when the artist’s twice exiled parents arrived at the immigration office in their new host country, their original family name al-Kiswani was changed to the Swedish-sounding Kiswanson. This origin story would – according to some reviewers [1] – enable the audience to gain an insight into the artist’s work by providing a key to decode the biographical elements that lurk in his articulation of sculptural mass and graphic line. Except that it does and doesn’t at the same time, because origin stories tend to afford access to the content of a work but not to its meaning.

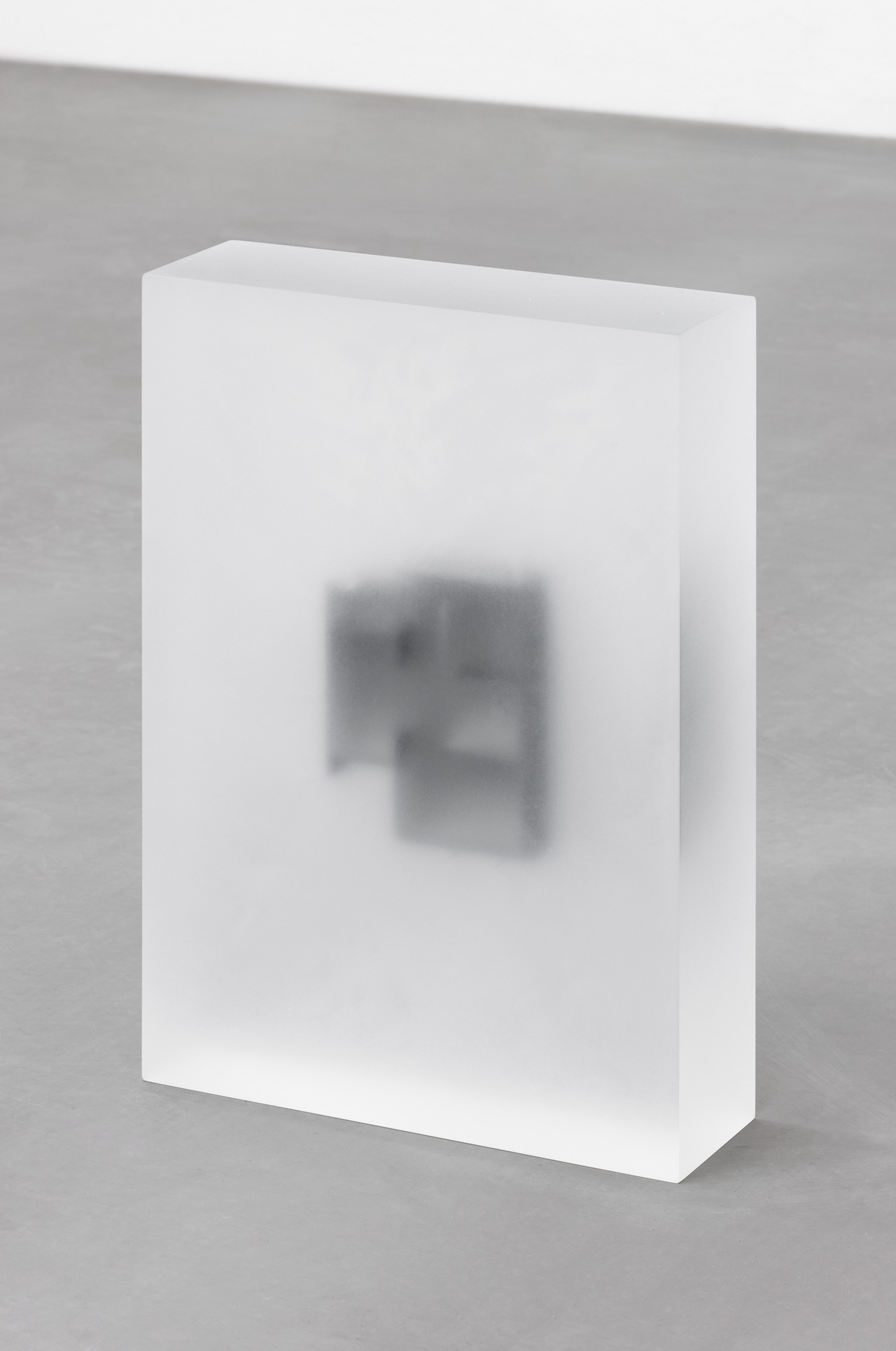

Tarik Kiswanson “Anamnesis,” 2023

One could construe Kiswanson’s work as a mode of cultural performance that creates the grounds for “appropriation and ownership in the alien place of non-ownership, that is, in the diaspora, the site of exile.” [2] For Anamnesis (2023), Kiswanson encased a metal model of a floor plan in a block of resin. It’s the floor plan of the apartment where the family lived, in a social housing complex that was demolished in the early 2000s, and the artist recruited the help of his three siblings to be able to reconstruct it. The fragility of recollections and the brittleness of childhood memories are solidified into an stainless steel plaque, embedded inside the resin block to create an object situated between transparency and opacity, whose promise of insight and intimacy remains unfulfilled, frustrating the viewer’s voyeurism – who doesn’t love a peek at the lives of others? – and whose meaning remains elusive even as it wears its content on its sleeve. The floor plan reappears in the embroidered canvases The Apartment (1972) and The Apartment (1995), both made in 2023, with red thread drawing tentative lines that seem to bleed onto the gallery floor. For the series of works What We Remembered (2012–ongoing), the artist reconstructed as sculptural shapes the pieces of furniture – like his grandfather’s filing cabinet – the family salvaged as they fled their home in Jerusalem, and which they kept throughout the years. Kiswanson thins out the solidity of the forms into grids that are as graphic as they are skeletal. The works’ brass strips were welded together by molten silver, which the artist extracted from family heirlooms. The act of sacrificing a beloved object to hold together a phantasmic field of recollections suggests a symbolic overdrive in which the role of the present is to mend the disjointedness of the past. It is perhaps noteworthy that a spoon – the object we use to feed babies and small children, with connotations of care and nurture – was among the objects the artist melted: the condition we call exile involves daily dealings with ghosts that demand their due, if not in the form of reparations or justice, then at least in the form of undivided attention.

Unsurprisingly, the demands the past makes of the present are difficult if not impossible to fulfil. Also unsurprisingly, Kiswanson often ventures into sites where meaning does not properly “line up.” Another work in the exhibition, a video piece titled The Reading Room (2020), shows a six-year-old’s unavailing attempts to read passages from books found in Edward Said’s personal library, housed at the Edward W. Said Reading Room at Columbia University, where the famous scholar once taught. The child stutters, speaking in a halting way, struggling to pronounce the syllables. Stuttering is a disorder of fluency, but one can also stammer when under duress or emotional distress. Kiswanson parallelizes the stuttering with the limits of a discursive framework by staging the child’s struggle to vocalize what Said read and wrote.

“Tarik Kiswanson: The Reading Room,” carlier | gebauer, Berlin, 2023–24

Edward Said was the most influential spokesperson for the Palestinian cause at a time when simply using the term “Palestine” was considered a political provocation. Kiswanson is an artist of Palestinian origin at a time when his very identity is considered a problem by many political actors in the Western world. No wonder there is an “unfinished business of sentimentality” [3] in the artist’s work, a tension between the need to clutch onto family memories and significant heirlooms and a nonplussed character, punctuated by disconnect and withdrawal from life. When personal biography is overdetermined by collective history, how can you tell belongings from unbelonging?

Often feminized, hence degraded, sentimentality has been recurrently conflated with excessive pathos or cheap emotionalism, but, as Laurent Berlant argues, sentimentality

is not just the mawkish, nostalgic, and simpleminded mode with which it’s conventionally associated, where people identify with wounds of saturated longing and suffering, and it’s not just a synonym for a theatre of empathy: it is a mode of relationality in which people take emotions to express something authentic about themselves that they think the world should welcome and respect; a mode constituted by affective and emotional intelligibility and a kind of generosity, recognition, and solidarity among strangers. [4]

From this perspective we could say that “the sentimental” names the space in which social reality finds symbolic fulfilment, a promise of recognition or a form of acceptance that can assure the stability of affect and identity. This might not be legible as political according to a Western idiom but is the very condition for political communities to emerge. To return to where I began, whereas the content of Kiswanson’s work can be tied to the Swedification of the family’s name, the artist is not simply telling us his story but trying to articulate a grammar of affinity, to make emotions intelligible in a way “the world should welcome and respect.” The difficulty of rightly framing the promise of reconciliation, of reciprocity, is perhaps the reason why Kiswanson’s work frequently feels like a metric of mourning. How some stories of exile, but not others, put pressure on empathy is how I would read the meaning of a work that often touches on despondency, without becoming a discourse on disenchantment but quite the opposite.

“Tarik Kiswanson: The Reading Room,” carlier | gebauer, Berlin, November 25, 2023–February 16, 2024.

Ana Teixeira Pinto is a writer and cultural theorist based in Berlin.

Image credit: Courtesy of the artist and carlier | gebauer, photos © Andrea Rossetti

Notes

| [1] | See, for instance: Cathrin Meyer, “For Tarik Kiswanson, Identity Is a Careful Balancing Act,” Frieze 237 (September 2023). |

| [2] | Pnina Werbner and Mattia Fumanti, “The Aesthetics of Diaspora: Ownership and Appropriation,” Ethnos 78, no. 2 (2013): 149–74, 149. |

| [3] | I am borrowing the expression “unfinished business of sentimentality” from affect theorist Lauren Berlant; see her book The Female Complaint: The Unfinished Business of Sentimentality in American Culture (Raleigh NC: Duke University Press, 2008). |

| [4] | Laurent Berlant, “Depressive Realism: An Interview with Earl McCabe,” in “Realism,” themed issue, Hypocrite Reader 5 (June 2011). |