BACKLIGHTING THE BLEAK Jules Gleeson on Anohni and the Johnsons “My Back Was a Bridge for You to Cross”

Ahnoni, 2023

The opening lines of Anohni’s track “Scapegoat” encapsulate the gloom and militancy that fill the singer’s fifth studio album, My Back Was a Bridge for You to Cross:

At first glance, this record addresses a moment of great struggle for the singer. A moment of both inward and global turmoil that resolves in anguish and even defeat. Yet when considered more closely, the album has a more hopeful, twofold intention: First, in face of the struggle any performer directly impacted by transphobia faces when addressing broader concerns, in a cultural context increasingly pressing them toward justification of their lives, Anohni offers no such justification. Second, and more personally, the album is a means of furthering her ecologist commitments through occult reflection (at least for those who choose to pursue her down a rabbit hole.)

While having found no shortage of accolades throughout her career, Anohni’s interaction with true stardom have always been awkward and faltering. While originally from Britain, Anohni seems to have limited interest for the country, despite her second album I Am a Bird Now winning the UK’s Mercury Music Prize in 2005, bringing her to pop prominence. At that point Anohni was genderqueer and still using her birth name publicly. It’s difficult to imagine such a triumph not being undercut by a minor scandal today, given the widespread transphobia in today’s British media (with anti-trans talking points once distributed by a certain type of feminist now a regular refrain of right-wing “anti-woke” commentators). In other words, rather than positioning her as a trailblazer for things to come, with hindsight, Anohni’s ascendency in her homeland was strangely out of time. Yet her highest moments of mainstream recognition in the US have proven still more troubling. Along with J. Ralph was nominated for an Oscar for her track “Manta Ray” from the 2016 film Racing Extinction, yet the Academy Awards organizers claimed to have cut her performance due to “time constraints”, while by her own account Anohni was never even asked to perform and found the experience “degrading.” [1]

So Anohni’s experiences with the highest possible mainstream exposure have repeatedly been of little use to her. Perhaps this plays some part in her turn toward the wearied and inwardly facing tracks of her latest release (which, while not embittered, certainly seem exhausted). Following her tremulous cover of Nina Simone’s unremitting “Be My Husband”, this latest album is a dedicated exercise in singing the blues. Also, as she explained in one interview, the record reflects her realization that the 1980s New Romantics who had originally inspired her to perform musically (especially Marc Almond) were heavily influenced by a transatlantic admiration for US soul singers of the 1960s. [2] But while the likes of her sometimes collaborator Boy George had stitched mournful vocals against a backdrop of lively drum-machine beats, Anohni’s rendition of this form veers downtempo, into unchecked bleakness. The mood of the album is identifiable from the track listing alone, with titles including “Why Am I Alive Now?,” “It’s My Fault,” “There Wasn’t Enough,” and simply “Can’t.” At first glance, the LP seems to signal a turn toward a more despairing register of introspection than Anohni’s audience has come to expect in recent years.

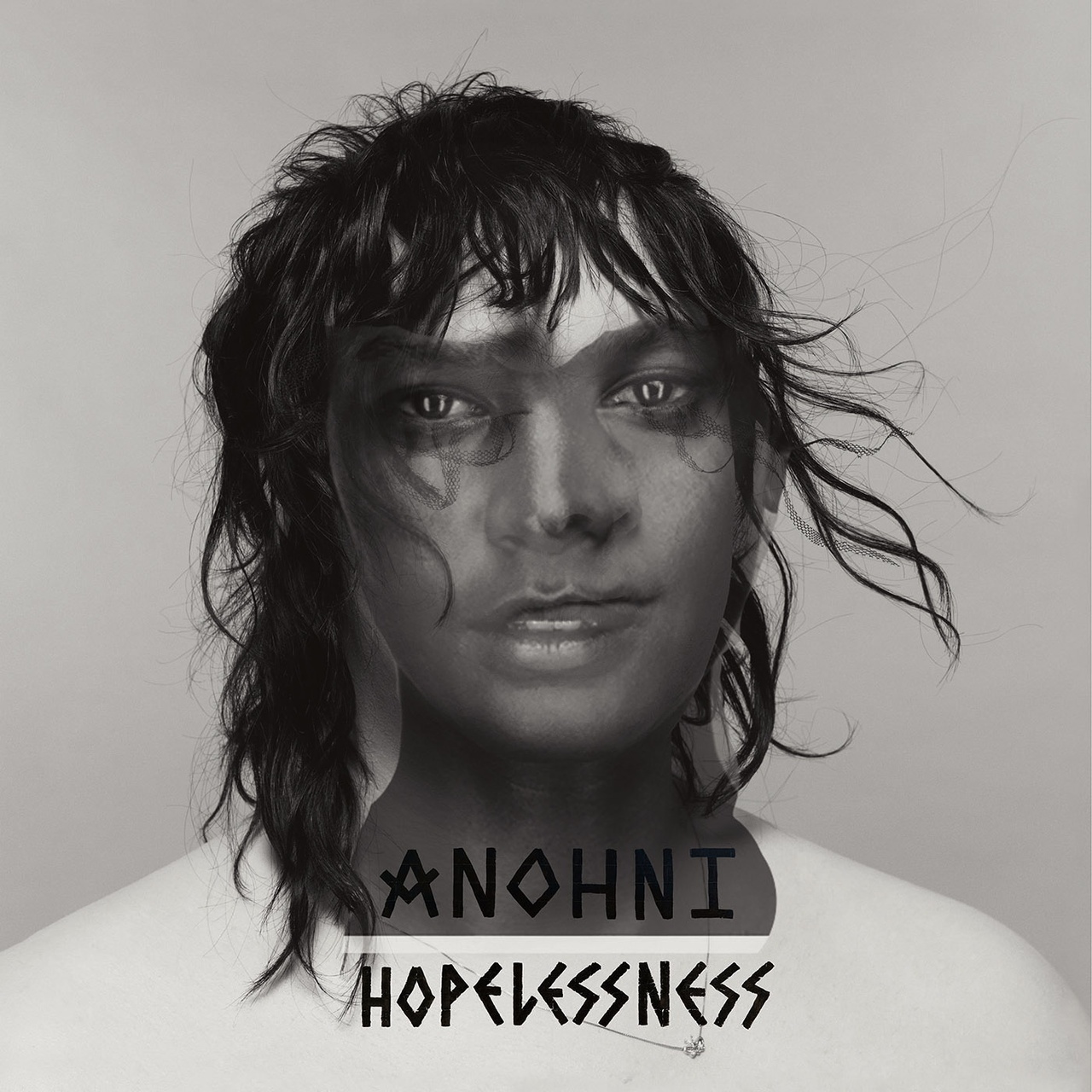

Previous releases from Anohni had been more overtly militant. The second single from 2016’s Hopelessness was titled “Drone Bomb Me,” and the protest single “R.N.C. 2020,” with an accompanying essay, pressed home her refusal to be digested as an overwrought torch singer. [3]

Does Anohni’s new album serve as a reversal of this hardened, politicized stance? I think not. A deeper meaning is found in the record’s accompanying cover and promotional texts posted by Anohni to her social media accounts. The album was composed with the canonical soul guitarist Jimmy Hogarth, contrasting with her previous track record of solo writing. Many tracks captured the first occasion she’d sung their written lyrics through, adding to the sparse and immediate sense that pervades it. My Back Was a Bridge for You to Cross is also the first album released under both her current name and with “the Johnsons,” her previous album Hopelessness having used only the mononym.

Yet while a stylistic departure, this album is also an act of return: it both burrows deeper into the influences that originally inspired Anohni to perform and provides an esoteric subtext directing attentive followers toward her career’s origins. Long before she was even using the name, the New York City underground was the original home of Anohni. Having arrived there as one the metropolis’s innumerable art students, she became a mainstay in both its drag and esoteric circles. More than a decade before her Mercury Prize, Anohni had established herself as a siren of countercultural happenings, performing her original works to dedicated audiences. She’d also collaborated with Lou Reed extensively across the 2000s. Reed’s canonical rock’n’roll status had been accompanied with longstanding accusations that he’d treated trans women simply as his silenced “muses” (appearing only second hand, and easily discarded). By contrast, in recording for a performance hosted by US tech giant AOL, Reed introduces Anohni in apparent awe at her delivery. At one point, Anohni asks if her headphones look “queer,” with Reed’s usual gruffness melting to open indulgence, reassuring her they actually make her head look smaller.

As well as immersing herself with those responsible for the canon of 20th-century counterculture, Anohni charmed prominent occult practitioners. Her early work was promoted through the then lively “neofolk” scene: David Tibet – creative mainstay of gnostic Christian act Current 93 – signed Anohni to his Durto label in the late 1990s and released her band’s self-titled first album. Their follow-up EP I Fell in Love with a Dead Boy featured a cover of Current 93’s “Soft Black Stars” (heavy vibrato a marked contrast to the original’s delivery as a cursed sing-song nursery rhyme). [4]

By this point, Anohni’s career was spent ably straddling the divide of willfully trashy gay culture and esoteric performance art. She’d founded the Blacklips Performance Cult, a theatre troupe blending drag and occult forms to stage over 100 one-off performances they always referred to as “plays.” [5] The troupe became a fixture at the Pyramid Club, the East Village’s avant-garde drag venue, and performed each Monday evening, becoming something of a clearinghouse for fresh talent throughout the 1990s.

While later winning mainstream success, Anohni never attempted to deny her underground past. After the Pyramid Club was permanently closed during Covid, the 2020s served as a juncture for Anohni to return to that moment in several forms. Anohni’s earlier fixture at the Pyramid was documented in a coffee-table book of archive photos compiled by Marti Wilkerson titled Blacklips: Her Life and Her Many, Many Deaths (Lou Reed credited as Anohni’s “back-up singer”).

So what role does My Back Was a Bridge for You to Cross play in Anohni’s persistent interest in public transformations? How does it follow from the “many deaths” of the Blacklips Cult? The album’s cover is a close-up on the face of legendary Stonewall Riots veteran Marsha P. Johnson. While musically informed by 1960s soul musicians, visually, the cover art returns us to that decade’s political street struggles. In recent years, invoking Johnson’s personal involvement in the street struggles against the police, and her later work as a community figurehead, has become a matter of course for US queer activists. Depictions of both Johnson and her erstwhile friend Sylvia Rivera have tended toward saintly. But more particularly, Johnson has always served as an emblematic figure for Anohni’s career. A post on Anohni’s Instagram recalled a chance meeting the two had fleetingly enjoyed only a few weeks before Johnson’s death in 1992, and Anohni had been creatively immersed in the community-wide grief that followed Johnson’s passing, staging the 1996 show The Birth of Anne Frank/The Ascension of Marsha P. Johnson. The event attracted luminaries of the radical drag scene and Stonewall veterans alike. In this sense, Anohni had tethered her career to Johnson’s memory years before she named her band after the civil rights pioneer.

This visual choice of her latest album’s cover art directs Anohni’s audience toward her career’s point of departure in New York City (and specifically the urgent need that existed at the time for defiant remembrance of earlier gay struggles). But through that point of focus, the framing of the shot serves another purpose: establishing a two-point visual reference with her previous album, Hopelessness. That album’s cover similarly zooms in on a face and shoulders, with several photo superimpositions making that photo’s features seem either in frantic motion or perhaps partially shrouded in shadow. Those features seem ambiguous (or ambivalent) along lines of sex or ethnicity. Next to the clear and defiantly joyous frontal of Marsha Johnson, we see a clear counterpoint: distortion and clarity, chaos and resolution. Why have these two contrasting photos of photos been set up to follow on from each other?

Anohni’s original self-release label was named Rebis Music, a reference to the alchemical symbol of a two-faced figure embodying the principle of the double-thing (“rebis” is drawn from the Latin res bina: dual or double matter). In alchemical traditions, moments of opposition follow into unification. Stages of putrefaction (rot) and purification (cleansing) were believed to first separate and then congeal opposing qualities. This allows for a new meaning to be drawn between what had previously been juxtaposed, a process marked by something appearing twice (which the alchemists often referred to as a “hermaphroditic” moment). To become divine was to be doubled. In that sense My Back Was a Bridge for You to Cross and its predecessor are linked: a contradictory repetition, or doubled substance. Clutter, tidiness. Harsh electronics and faltering guitars. Denunciations of imperialism and inward-facing laments. Rejection of imperialism and acceptance of culpability.

While a more subdued and contemplative work than its predecessor, Anohni’s latest album demonstrates that grand statements do not appear at odds with personal angst or openly working through traumatic breaks. With this in mind, the album serves less as a work of miserabilism and more the completion of a public act of alchemy: the toxin of mainstream breakthrough transmuted into a continued call for struggle. Rather than a star, Anohni would prefer to turn back into a bird.

This point has been pushed through with Anohni’s accompanying press interviews, which have provided an unflinching critique of Western society. As well as denouncing their warfare and widespread phobia, she charges the world’s political regimes with sacrificing ecological concerns due to the fixation on domination found in the cultural norms of Abrahamic religions. These father-worshiping creeds have suppressed any space for a female divine form. This has resulted in a masculinist cultural chauvinism — now responsible for rendering the planet uninhabitable for humanity. Instead of accepting that they are simply mute “victims” of consumerism, Anohni urges listeners to acknowledge that they’re full participants in the ecosystem’s destruction. Although this may seem a political message staged at the grandest level of historical and cultural abstraction, it follows years of Anohni supporting more specific ecological struggles – such as the land claims of Indigenous Martu people to resource-rich territories commandeered by local mining companies in 2015. [6]

While not explicitly advocating for an esoteric turn in response to these dire ecocidal circumstances, or promoting any one older form of faith and ritual practice, Anohni has still laced around her music a more profound meaning through the calculated procession and packaging of her recent releases. Together, Hopelessness and My Back are a working of opposing repetition, a purposeful reversal that offers us a completed struggle against society as it stands. While explicitly declaring that a scapegoat is all she can be, tacitly, the surrounding materials to these dirges show how each of us might become all kinds of things, across a lifetime (or a career).

Through this paratext directing attentive fans toward the origins of her career, My Back Was a Bridge for You to Cross serves as a two-fold work: at first glance, it is a mournful, strident and sometimes despairing set of reflections upon personal turmoil and loosely pictured political struggles. But upon another view, the album is a full-throated celebration of the underground origin of her career, and a continuation of the overt support for militant systemic change that she has locked into in recent years. Anohni hopes to show the world how grief and revolt are possible at once, how moments of ruination and apparent despair might still fuel the will for a world to change.

Anohni and the Johnsons, My Back Was a Bridge for You to Cross, Secretly Canadian, 2023

Jules Gleeson is a writer from London who lives in Berlin. Her essays, reviews, and interviews are widely published. She has performed stand-up comedy and given philosophical lectures internationally, at communist and queer events. Jules edited the anthology Transgender Marxism (Pluto Press, 2021) with Elle O’Rourke and is now writing a book on intersex liberation and the 1990s.

Image credit: 1. Photo Anohni with Nomi Ruiz, © Rebis-Music; all images courtesy of Pitch Perfect

Notes

| [1] | Anohni, “Why I Am Not Attending the Academy Awards,” Pitchfork, February 25, 2016. |

| [2] | Chris Dart, “Anohni is Paying Tribute to Her Influences’ Influences,” CBC Arts, Q With Tom Power, August 14, 2023. |

| [3] | Anohni, “Anohni on Her New Track R.N.C. 2020: ‘It's me, screaming in the past, for the present,’” Guardian, September 3, 2020. |

| [4] | “[Anohni] and the Johnsons: ‘Soft Black Stars,’” YouTube video uploaded by Mark Nevsky, 4:41. |

| [5] | Tricia Romano, “Blacklips Performance Cult: The Gothic Drag Theater Troupe Where Anohni Got Her Start,” Red Bull Music Academy, May 16, 2016. |

| [6] | Paul Daley, “[Anohni] Hegarty, the Martu and the Mine: Land Custodians Fight Corporate Might,” Guardian, June 19, 2015. |