The Joke of Painting Alexander Alberro on David Hammons at L&M Arts, New York

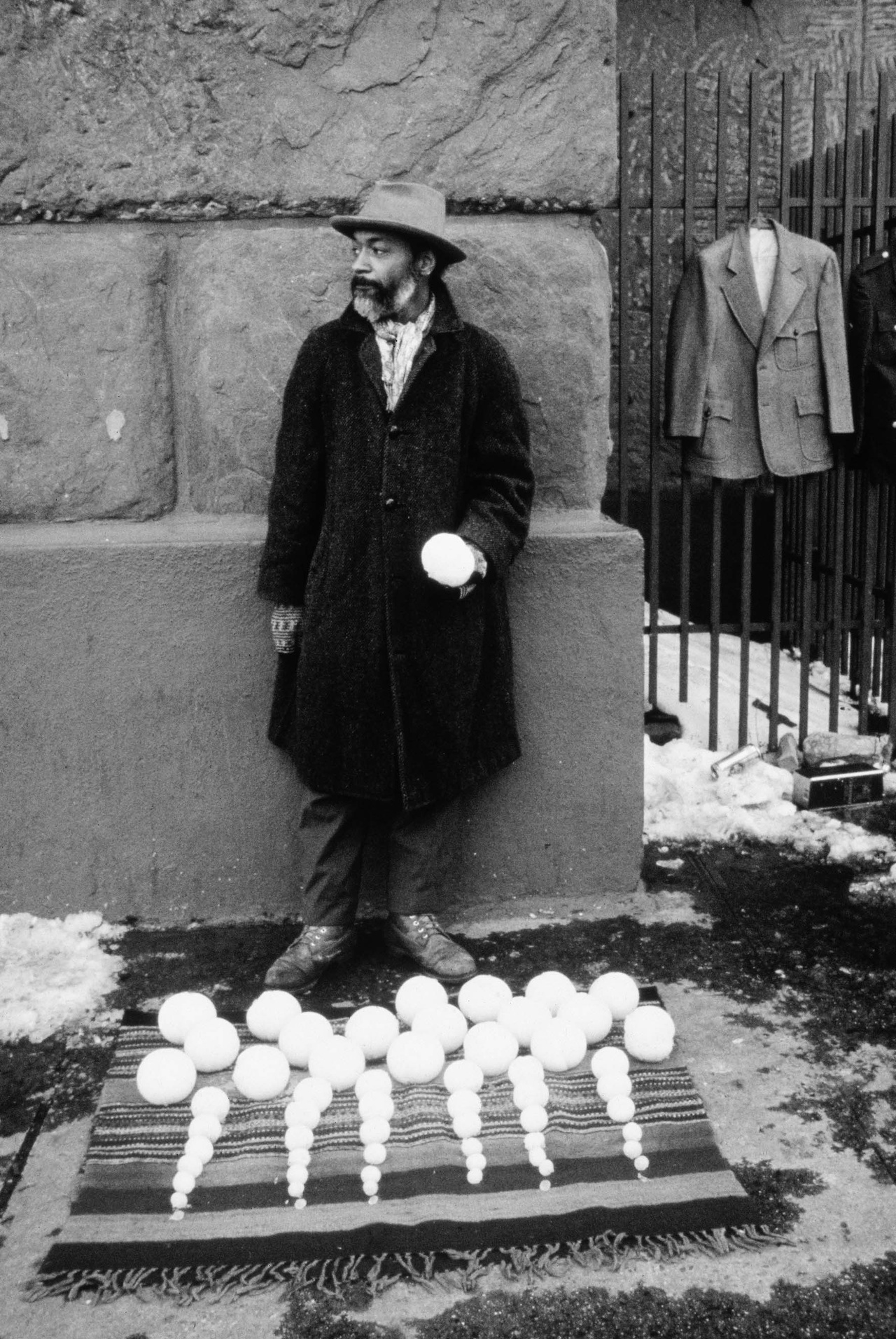

David Hammons, “Bliz-aard Ball Sale,” 1983

Art often functions in analogy to the joke. Its effect is produced by the solution of an initially unintelligible, incomprehensible or puzzling proposition. Like the joke too, much art articulates that which generally cannot be introduced into public speech, and brings to the surface that which is normally hidden.

The work of the New York-based artist David Hammons has long traded in a sly sense of humor with a sharp polemical edge. From early sculptures and performance pieces such as “Spade in Chains” (1973), with its pun on racism and slavery, and “Pissed Off” (1981), which had him urinating on a Richard Serra sculpture, to more recent installations such as “Global Fax Machine” (2000), with machines spewing faxes from the ceiling, and “Which Mike Would You Like To Be Like?” (2003), featuring three microphones (i. e., three “mikes”) representing three Michaels: Jordan, Tyson and Jackson, tongue-in-cheek puns, word plays and jokes have been mobilized by Hammons to formulate ironic commentary on lived experience of urban life in the US and the operation of the contemporary art world.

Hammons’ recent suite of untitled assemblages at the L&M Arts gallery in Manhattan’s snooty Upper East Side operates along similar lines. This time the focus is on one of the central myths of modernist painting, which the assemblages at once restage and explode with the same kind of irreverent wit that has characterized the artist’s work. L&M Arts is a secondary-market gallery, with its primary source of income generated by the reselling artworks by painters of the New York School, the first made-in-the-USA artistic avant-garde. The American Art critic Jerry Salz reported four years ago that Hammons initially approached the L&M Arts “out of the blue” with an idea that the artist claimed “would perfectly fit the gallery’s history”. The result was a 2007 show of six vintage dress forms, each outfitted with a full-length fur coat. Two of the coats were of mink pelt, and the others were of fox, sable, wolf and chinchilla. Hammons and his wife Chie sullied the backs of all of these coats, turning them into paintings, and the paintings in turn into a reflection on the marketing of luxury objects.

For this year’s exhibition, his second at L&M Arts, Hammons draped ten or so big, abstract oil canvases composed in a luminous palette and all-over style with large sections of various grungy materials, including crumpled plastic garbage bags, an old and ragged terrycloth towel and industrial tarpaulins of the type that housepainters typically use to protect furniture and floors from stray drips of paint. Aggressively gouged, bitten or scorched holes here and there in the cheap plastic or tarps allow the spectator glimpses of the generic Abstract Expressionist compositions beneath. Some of the industrial or trash materials that shroud Hammons’ paintings are stitched together by hand, others seem to be sewn with a machine, and yet others have been glued or pressed onto the canvas, seemingly while the paint was still wet. The multiple folds and crinkles of the banal factory-made materials hung in layers over the compositions double as expressionistic gestures and produce a dramatic effect. In one instance, the tarp is missing, and a castoff, decrepit wooden wardrobe has been shoved up against the canvas instead, obscuring the splotches of lavender magentas, mint greens, pastel reds and turquoise blues. And two pieces on the gallery’s second floor consist of just the vandalized industrial elements – translucent plastic tarpaulins and opaque black garbage bags ripped, torn, and nailed to the wall through embedded grommets – with no “paintings” underneath.

Hammons’ compositions are as dependent on the history of abstract painting as they are on the Duchampian readymade, Dada collage and Arte Povera sculpture. The works integrate and turn these legacies, thereby corrupting the machine-made elements with abject refuse, and investing the painterly aspect with a renewed sense of aesthetic desublimation that the whole repertory of rips, scratches, gouging, and abrasions implies. The resulting assemblages recall the iconoclastic form of self-expression with trash materials that characterized the work of the mid-twentieth century informel painters such as Alberto Burri or Antoni Tàpies, though they conspicuously lack the existential, humanist-driven impulse of these European abstract artists. The large scale, garish colors, and thick, spontaneous-seeming brushstrokes of most of the paintings directly relate to the work of the New York School, and hence to the commercial “history” of L&M Arts. Hammons’ canvases, insofar as we can see them, restage Abstract Expressionism’s strange synthesis of formal rigor and idiosyncratic passion, as well as its play on figure-ground versus all-over compositions, and stained versus impastoed surfaces. That the apotheosis of this heroic art movement was prominently featured in the Museum of Modern Art’s blockbuster exhibition, “Abstract Expressionist New York”, during the run of Hammons’ show, was surely not lost on the artist. Nor was the fact that L&M Arts has been the site of no less than seven solo exhibitions of the work of the New York School painter Willem de Kooning. Indeed, it is the œuvre of the latter that Hammons’ abstract pictures resemble the most. The ludicrously vulgar colors and emotional high heat of the paintings are derived whole cloth from de Kooning. And as if that was not enough, the broad sweeps that dominate Hammons’ canvases were evidently produced with the help of the type of large brush de Kooning often employed to endow his expressionistic compositions with a virile swagger. But if the reference is de Kooning, it is not as much an homage to the intuitive and technically-gifted painter as an oblique revamp of Robert Rauschenberg’s outrageous 1953 gambit “Erased de Kooning Drawing”. Hammons’ riff, it seems, is more one of cancellation than of eulogy, an attack on the medium and style of de Kooning rather than an embrace.

The compositions at L&M Arts are as sculptural as they are painterly. With their draped membranes often touching the ground, the painterly objects establish a continuity between the surface of the wall and that of the floor. By linking the two axes in a position of obvious correspondence and parity, the artist erodes the boundaries of the classical categories of painting and sculpture altogether, and makes the work in its evident flow and self-determination directly respond to the beholder’s own bodily experience. Not only is the spectator discouraged from lifting the veils of trash that obscure the ostensibly pristine canvases beneath, but she must also be attentive not to trample on the sculptural elements of the compositions that flow into the space of the room.

Abstract art in the twentieth century was widely embraced as the shortest route to universal meaning and significance, a phenomenon that has waned but not entirely disappeared. Many of the abstract compositions of Wassily Kandinsky and Kasimir Malevich, for instance, or those of Dan Flavin, Agnes Martin, James Turrell, and, more recently, artists such as Olafur Eliasson and Paul Chan, claim (to a greater or lesser degree) a relevance and subject beyond representation, a meaning unspeakable otherwise, yet held in and made concrete by the organization of form and color (and increasingly sound). The emphasis is alternately on liberation, transcendence and foundational experience. The spectator, in turn, is assured that concentrated speculation on the interior, virtual space of the work will lead to a moment of sudden intuitive understanding. In order to maintain this belief when confronted with the testimony of her own eyes, the viewer often has to act as if there is much more there than there actually is; as if, to borrow from the classic tale, the emperor is decked out in exquisite new clothes. Hammons’ compositions offer little in the way of mythical experience. On the contrary, they represent a kind of fervid deathliness, one befitting an art surviving the death of art. The spectator, in her attempts to solve the riddle by peering through the tears and gapes in the tarpaulins or around the edges and margins of the compositions, cannot escape the reality that there is little of substance beneath the damaged facade. This is nowhere more apparent than in the two stunning assemblages on the second floor of L&M Arts, the last in the exhibition’s narrative order, that consist solely of double, canvas-size curtains of mutilated industrial plastic affixed to the gallery wall. Here the viewer is confronted with the bare truth of painting; the problem put forward by the bewildering objects is solved. The emperor is naked after all. Some will undoubtedly quibble that there is nothing new about this insight. The negation of interiority, of any solid, plotted depth, is as central to the history of modern art as is the passage from content and the division of signification to a phenomenology of the surface, from representation to presentation. But Hammons’ insistence is not on the work’s facticity. His recent assemblages go beyond a refusal of inner necessity and presentness. They even exceed the late-twentieth century notion of art as a field within what Daniel Buren once referred to as “critical limits”. For Hammons, art is a mischievous game beyond limits. It perverts the logic of forms of belief, conventions of knowledge, and ways of seeing, to make the repressed visible in a manner that only an excellent joke could accomplish.

Alexander Alberro is the Virginia Wright Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art History at Barnard College and Columbia University where he teaches modern and contemporary European, U.S., and Latin American art, as well as the history of photography.

Image credit: Dawoud Bey; Mnuchin Gallery, New York.