INFORMERS Daniel Keller on Peter Fend at Barbara Weiss and Oracle, Berlin

“What’s your CIA code name?” That’s the first question Peter Fend asked me when we first met. “I didn’t think I had one...,” I replied. “Mine is _______,” he said, dead serious. Who knows if that’s true or if he’s ever even engaged with the CIA. But then again, given Fend’s profile – well enough established to have shown in Documenta in the ’90s and collaborated with the likes of Richard Prince as early as the late ’70s and yet still a somewhat liminal figure – who am I to assume he wouldn’t be taken seriously by the intelligence community as a potential subversive.

Peter Fend is indeed a man filled with insurrectionary, dangerous ideas – schemes so grandiose they would topple governments, dismantle international treaties, and completely transform the global energy infrastructure were they to ever be enacted. Luckily for the powers that be, Fend is also an utter failure. Yes, he’s an extremely accomplished artist, with a forty-some-year long CV that would impress anyone – the consummate veteran scenester, frequently finding himself in intimate proximity to power and fame, but without much to show for it besides insight and entertaining anecdotes – and a self-declared failure none the less.

"Peter Fend: to be built," Oracle, Berlin, 2015. installation view

"Peter Fend: to be built," Oracle, Berlin, 2015. installation view

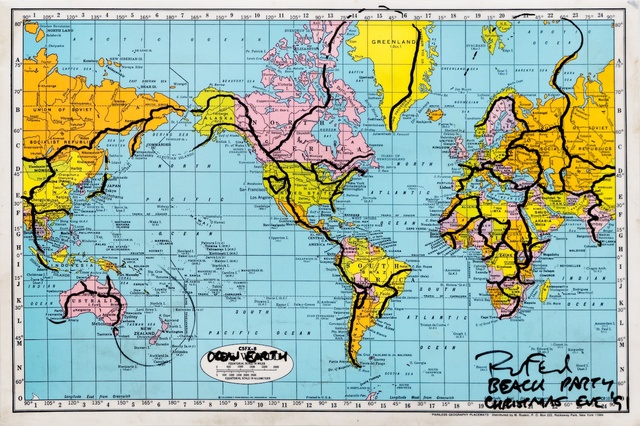

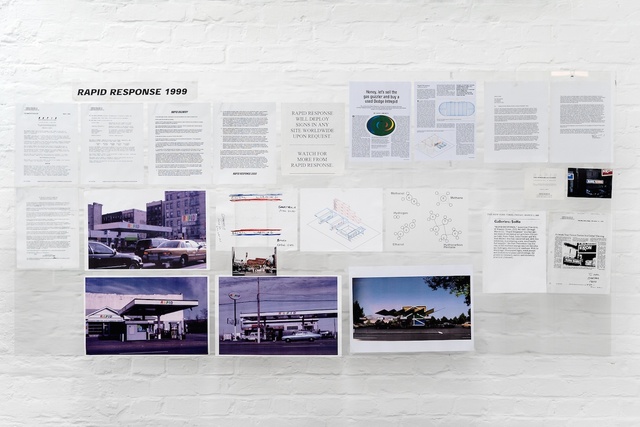

The art Fend showed this fall in “to be built” (a joint exhibition at Galerie Barbara Weiss and the Oracle project space, both in Berlin) presented an assortment of works on paper, prints on fabric, signs of Plexiglas and neon – all made between 1979 and 2000. Effectively, this display condensed the (variously expat) American artist’s expansive blend of radical utopianism and paranoid bitterness into a digestible mini-retrospective that looked backwards as much as it did towards a hazy future. For those who know Fend’s work, this was his standard playlist on shuffle. Most prominently, this included his trademark annotated maps, which aim, for example, to redefine national borders according to shared drainage basins, or, say, to overturn electrical company monopolies with the mass adoption of a cryptic alternative energy source referred to only as “SEA GAS.” Another details a series of megastructures, rendered in squiggly red marker, originating on Delancey Street in lower Manhattan and stretching across the East River through Brooklyn and into Jamaica Bay, proposing what would no doubt be the most costly and controversial US public works project in history, displacing hundreds of thousands of famously angry New Yorkers in the process. That being said, the works are beautiful – as images and as ideas. It is true of Fend that, no matter the subject’s complexity (politically, technically, economically), he always maintains an aesthetic unity, which in turn gives his art strong visual agency. A seminal example is his “RAPID Methane Gas Station” (2000), installed, for this show, at Oracle: a pristinely fabricated gas pump standing in the middle of the gallery, its corporate aesthetic is immediately legible to a younger generation of artists who have gravitated toward similar visual strategies. Yet the difference is, with Fend, that this sculpture is not a sly joke about cynically generating hot air or “energy” by circulation of an art object through networks and the market – he actually tried and failed to make a methane gas station corporation.

Peter Fend, "RAPID Methane Gas Station," 2000

Peter Fend, "RAPID Methane Gas Station," 2000

However, it is precisely that which makes Fend’s work so compelling as an art practice that also ensures its continual inability to ever be actualized as the architecture Fend intends it to be. An art audience hungry for classic outsider avant-garde attitude and exceedingly tolerant of ambiguity can eat up Fend’s word stacks – as long as they’re approached as absurdist concrete poetry. But once it becomes clear that Fend is actually, probably, trying to persuade the viewer to write a letter to their congressman about constructing a municipal artificial feather salt basin recycling system, “serious” people’s eyes begin to glaze over. The conceptual link between Fend’s visionary earthworks and the pipe dreams of Silicon Valley visionaries is undeniable. But I’m quite sure that where Peter Thiel would employ a professional graphic designer and run a few cost-benefit analyses before asking anyone to take his fantasy of floating megapolises seriously, the earthworks in Fend’s “to be built” are definitely never going to be built. The assorted maps, diagrams, text, and sculpture in this show, as in previous shows, are trapped in a state of permanent potentiality and a long way from persuading anyone in a position of power of much of anything.

With Fend, a lot of the content washes over you, but the distilled position is crystal clear. In fact, if he weren’t so persistent and earnest about the whole thing, one could almost read what Fend does as an epic troll on the impotence of eco-art and institutional critique. But if he takes his ideas so seriously, why does he not treat them with the care and respect (and necessary compromises) that would allow their actual development? It is as if the negative energy of surefire rejection feeds some internal combustion engine – one propelled by the extreme energy imbalance between Fend’s comically grandiose, utilitarian schemes and their hand-scrawled and frequently embittered presentation. And you have the sense that if any of his projects were to be actually tested on a workable scale and failed, this would utterly shatter his fragile but arguably comfortable position of the perpetually rejected soothsayer, far too wise for his time but always proved right in “the end.” But what thinking artist couldn’t empathize with this frustration? Fend has continually positioned himself for bitter defeat and rejection throughout his near half-century of production by stubbornly refusing to leave an abusive relationship with an art world that is at best utterly insufficient in clout or capital to implement any of his radical proposals and ultimately indifferent to the content and intents of his work.

Occasionally, I too find myself frustrated by the limitations of the artist’s position; the inability to really effect change. I daydream about quitting art and becoming a terrorist, each attack a meticulously planned spectacle with undeniably precise efficacy. Occupy the NYSE Data Center, set the Frieze tent on fire, shoot up a Christie’s Day Sale, etc. My guess, even if Peter Fend’s CIA code name is _______, is that scrawled in red marker on the bottom of his top secret file are the words “ARTIST, HARMLESS.”

“Peter Fend: to be built,” Galerie Barbara Weiss and Oracle, Berlin, November 12–December 19, 2015.

Daniel Keller is an artist from Detroit. He is currently based in Berlin. Twitter: @DnlKlr

Notes

| [1] | Peter Fend, "Beach Party World Map," 1991 |