BODY AS VOID Carlos Kong on Christopher Aque at Sweetwater, Berlin

“Christopher Aque: A void,” Sweetwater, Berlin, 2021, installation view

“The people in the street seem incredibly alive to me, incredibly in life; I envy them,” the French writer Hervé Guibert noted in his journal as he neared his untimely death from AIDS. [1] Guibert’s wandering gaze receives the aliveness of the urban passersby, an everyday vitality that his illness has foreclosed. His remark reveals how illness divides, separating those who can from those who cannot lay claim to intimacy, sociality, and public space because of bodily debility or the risk of infection. Decades later and amid another – albeit a very different – pandemic, Guibert’s observation resonates with Christopher Aque’s solo exhibition “A void” at Sweetwater, Berlin. Across photographs, a fountain-like sculpture, and a text written by the artist, Aque explores how prophylactic restrictions on distance and bodily contact reshape sexuality, desire, and the public realm from within the pandemic’s protracted present.

At the center of the exhibition is Double Negative (Swapping Spit) (2021), a two-part sculpture that operates as a fountain. Two black acrylic cubes sit within two shallow water-filled plexiglass basins, with water flowing between them via transparent tubing. A jagged off-white square of kiln-fired glass sits atop each black cube, an instance of Aque’s deft combination of handmade elements with industrial materials and technological process. The sculpture gestures formally to minimalism (Judd) and functionally to early conceptual systems, such as Hans Haacke’s Condensation Cube (1963–68), or his tubular Circulation (1969). Inside each black cube is a germicidal UV-C light that disinfects the water, neutralizing potential contaminants before it flows into the proximate sculpture. The work’s subtitle, “Swapping Spit,” makes explicit the sculpture’s analogy of sexual contact, whereas its title, “Double Negative,” points to sexual status and the surveillance of infection. Being “negative” is a designation that disciplines and moralizes in relation to biopolitical norms: beyond a desirable Covid-19 status in our pandemic present, it has long signified, in queer parlance since the AIDS crisis, the absence of HIV. Double Negative thus evokes the enduring sexual metaphors of infection as a form of pollution that requires sanitation – in circulation since the first outbreaks of syphilis – while visualizing how immunity is a new prerequisite identity for intimacy today. [2]

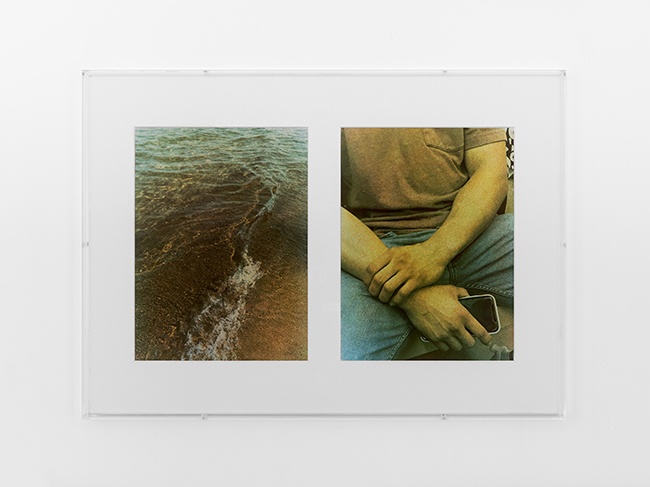

Six photographic diptychs, each titled either Ebb or Flow (all 2021), are framed in acrylic cases and hung around Aque’s central sculpture, referencing its bipartite structure and rectangular plexiglass basins. Each diptych depicts a voyeuristic snapshot of a male body in public space on one side and a close-up of a wave breaking on a shoreline on the other. During the lockdown, Aque turned his bathroom into a photographic darkroom, eventually developing the diptychs in his bathtub. Though the images were initially taken on handheld digital cameras, the artist printed the photographs using a gum bichromate technique. In this 19th-century photographic process, colors are individually exposed and laboriously layered on top of one another, condensing into an image. The diptychs’ washed-out cerulean and sepia tones give off a retro feel, throwing into relief the pandemic’s splitting of time into a distant “before” and a not-yet “after” while conjuring nostalgia for the less restricted (at least seemingly) pre-Covid moments of intimacy, spontaneity, and publicness.

Christopher Aque, “Ebb,” 2021

The Ebb and Flow diptychs offer contrary positions regarding the fraught status of proximity and distance amid the pandemic and its aftermath. Upon first pass, the images affirm the post-lockdown return of bodily intimacy in spaces of social assembly. “Life resumed in a rush of bodies clipping past, the ebb and flow of shared space,” writes Aque in his exhibition text, describing a post-vaccination outing in public where he encountered the aliveness of the men in the street who populate his homosocial photographs. [3] The emergence of the photographs from a bathtub – a space that holds the body – triangulates a carnal encounter between Aque’s gaze, the viewer, and the photographed body. This affective network of queer desire is underscored by its ebb and flow of fluid and heat exchanges, across bathwater, the photographs’ chemical developers, and the waves and sweating bodies (two runners and a swimmer) captured by the camera. In the photographs of the waves, liquidity becomes existential, eliciting “the oceanic feeling” that Freud characterized as “the sense of being one with the external world.” [4] The post-quarantine onrush of unconfined intimacy in the diptychs invokes this “limitless, unbounded – as it were, ‘oceanic’” feeling, which nevertheless, as Freud maintains in an unexpected resonance with the necropolitical present, offers “no assurance of personal immortality.” [5]

If the diptychs uphold the bodily intensity of a life resumed, they simultaneously point to intimacy’s ambivalences and impossibilities. Aque utilized the UV-C light to develop the photographs; “the vitality of the snapshot” is thus contingent on the symbolic decontamination of the imaged bodies. [6] The germicidal light source stages the body’s fortification and withdrawal: scientists have proved the efficacy of UV-C light in deactivating airborne coronavirus, yet the light is also hazardous to skin and eyes. The photographs’ aura of bodily contact is doubly distanced, mediated not only via the UV-C light’s prophylactic disinfection but also through the technology of Aque’s camera and what it registers. In the voyeuristic shots, half of the men have their iPhones present, cuing the displacement of sex and sociality onto dating apps and social media. Half, moreover, are headless, reduced to anonymous torsos, and all are alone. There is an implicit cynicism in Aque’s romance of embodied encounters, one that nonetheless reflects the ongoing constrictions of supposedly “shared space.” The post-pandemic body never fully appears but remains a void, a figure at twice remove whose intimacy is reliant on the invisible borders of immunity and technology.

Aque’s brief exhibition text grounds the context of the exhibition in the pandemic and narrates his process of photographic production. The text has an overdetermining effect on the show’s nuances, dictating an interpretive context over the photographs’ and sculpture’s varied aesthetic references and their open-ended and poetic stance toward contemporary body politics. It is hard to overlook the ruse of sincerity in the text: “I didn’t get on the subway again for fourteen months,” writes Aque, after leaving his last in-person workday, with a bag of toilet paper rolls and masks in hand. “The small joys of artisanal cheese or Amazon packages being delivered alternatingly punctuated the wail of ambulances rushing down Nostrand Avenue,” the artist nonchalantly recalls. The distance thematized in the exhibition – of bodily desire under shifting bio- and technopolitical regimes – is also the work’s distance from the disparaging conditions of racial, gender, and class inequality that offered survival and comfort for some and social and physical death for others. One is left wondering: What about the duress of the subway-riding precariat and Amazon deliverers whose labor was deemed “essential” in the pandemic because of its disposability? Can Aque’s post-pandemic flânerie in “shared space” in any way bear on the radical transformation of New York’s urban space in the pandemic’s crucial overlap with the collective grief and hope of the Black Lives Matter protests? And where is the misery of Trump’s America? In spite of Aque’s subtle portrayals of distance and intimacy, a deeper consideration of the body’s entanglement in the pandemic’s social and structural devastation is left a void.

“Christopher Aque: A void,” Sweetwater, Berlin, September 15–November 6, 2021.

Notes

| [1] | Hervé Guibert, The Mausoleum of Lovers: Journals 1976–1991, trans. Nathanaël (New York: Nightboat Books, 2014), 506. |

| [2] | On the sexual metaphor of illness as pollution, see Susan Sontag, AIDS and Its Metaphors (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1988), 17. |

| [3] | Quoted from the exhibition text. |

| [4] | Sigmund Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents, in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol. 21, 1927–1931 (London: Hogarth Press, 1961), 65. |

| [5] | Ibid., 65. |

| [6] | On “the vitality of the snapshot,” see Moyra Davey, “Notes on Photography and Accident,” in Index Cards (London: Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2020), 37. |