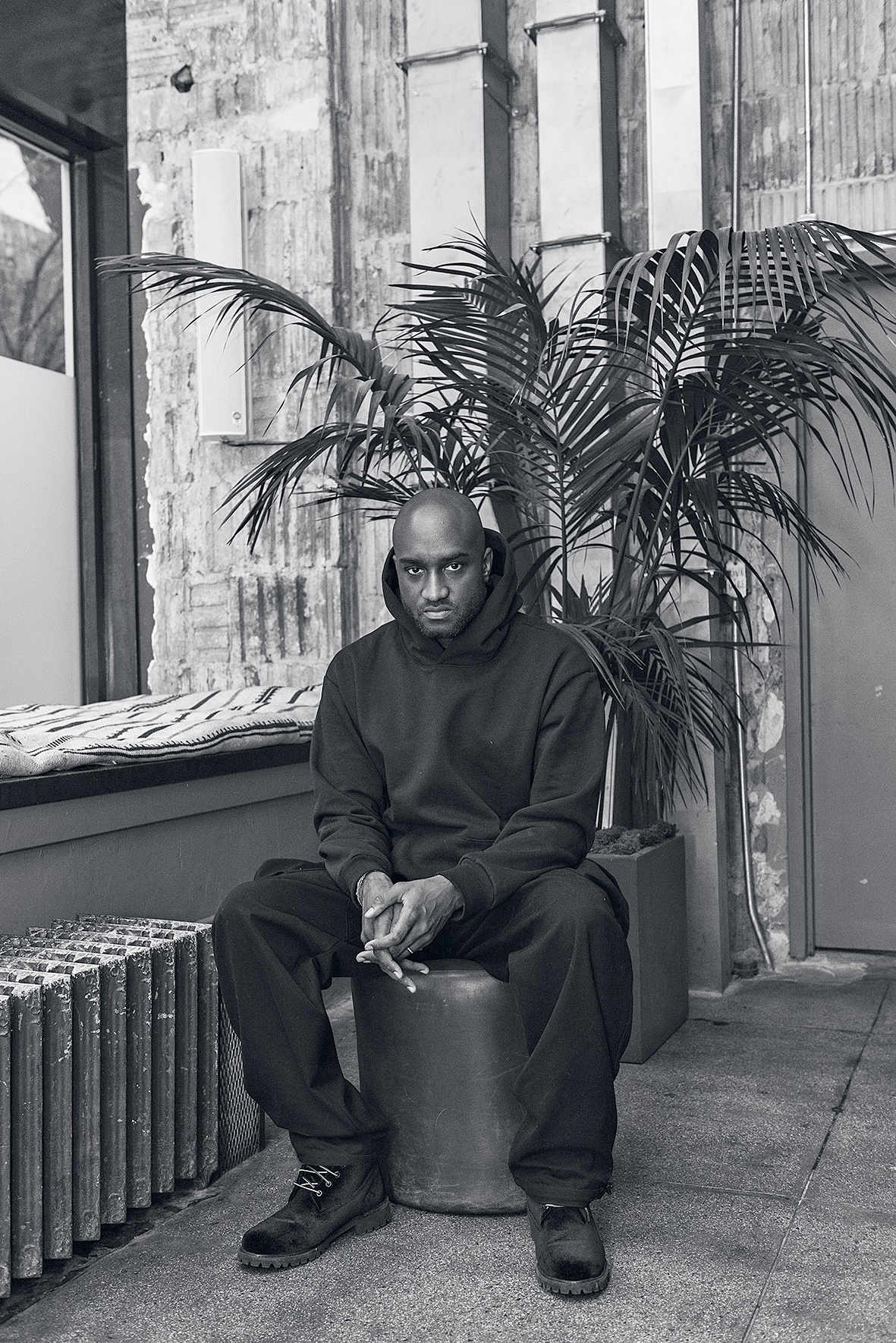

VIRGIL ABLOH (1980–2021) Eric Otieno Sumba

Virgil Abloh

It’s not every day that two notable Black men are seen sobbing into each other’s shoulders, as Virgil Abloh and Kanye West did at the finale of the former’s 2018 Paris Fashion Week show to the astonishment of hundreds of fashion people. Many will remember the Ghanaian American designer for that first of a handful of shows he presented as artistic director of Louis Vuitton’s menswear line and for his role as founder and CEO of Milan-based luxury streetwear label Off-White. The wind of change in a black T-shirt that Abloh represented at Louis Vuitton was cautiously well received by industry leaders, catapulting an already very well-known designer to levels of fame that many of his peers will never attain.

The general reception of Abloh’s work often straddled the line between fierce contestation and euphoric celebration. Yet, as the outpouring of grief upon the announcement of his death showed, it is his “immaterial” legacy – his kindness, generosity, and readiness to lift others – that shifted culture. Abloh understood his job, but, perhaps more importantly, he understood the assignment. He knew what was to be done, and he did it quietly, often late at night after what must have been arduously long days. For Abloh, sending encouraging DMs to up-and-coming creatives was seemingly on par with creative brainstorming sessions at Off-White or LV, because he knew what it meant to be seen and recognized: to have one’s vision and reverie be taken seriously enough and to be given a chance.

Behold the dreamers in tearful embrace! For the many onlookers who were captivated by the sight of two men brought to tears by sheer joy, and the hundreds of thousands more who watched countless clips of that moment online, the loaded seconds of West and Abloh’s embrace carried the weight of a voracious curiosity for insight into the lives of men with phenomenal creative outputs. There is something to be gleaned from Abloh’s atypical but incredibly successful career in that one fleeting moment. With the benefit of hindsight, the Abloh-West bromance partly explains the fuss that many made of Abloh while he was alive and that many are now catching up to after he succumbed to cardiac angiosarcoma, a rare form of cancer, at only 41.

Do not ask your childrento strive for extraordinary lives. [1]

Virgil Abloh was born on September 30, 1980, in Rockford, Illinois, to Nee and Eunice Abloh, Ghanaian immigrants. He earned a bachelor of science in civil engineering at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 2002. As a child of West African parents, the teenage Virgil Abloh felt that becoming an engineer was probably the least he could do to honor their sacrifices in migrating across the Atlantic from Ghana to the US. Abloh was pursuing a master’s degree in architecture at the Illinois Institute of Technology when he gravitated toward fashion, finally putting to work some of the skills his mother, who worked as a seamstress, taught him. Powered by the design concepts he studied at school and by Chicago’s budding street culture, Abloh began designing T-shirts and contributing to the popular streetwear blog The Brilliance.

In 2007, Kanye West met Abloh while Abloh was working at a Chicago screen-printing shop, Custom Kings, and West hired Abloh as his creative assistant for the merchandising and graphics for his Graduation album. The two also worked on West’s first sneaker collaboration with Louis Vuitton in 2009, and Abloh became the creative director of West’s creative agency, Donda, in 2010. Before interning together at Fendi in 2009 – where, according to LV CEO Michael Burke, they were “disruptive in the best way” – West had taken a few friends, Abloh included, to Paris Fashion Week, hoping to find an industry that shared in their excitement for the multiple new directions fashion could potentially take. The experience was sobering; as Abloh put it, “We were a generation that was interested in fashion and weren’t supposed to be there. We saw this as our chance to participate and make current culture. In a lot of ways, it felt like we were bringing more excitement than the industry was.” [3]

We did education for doing,not stretching, pushing, challenging, hoping,until we had no choice. [4]

Abloh launched his first brand in 2012. The New York City–based Pyrex Vision took deadstock from designers such as Ralph Lauren and transformed the items into a new brand by making minor adjustments or screen printing slogans on them, an overt minimalism that Abloh carried on to many of his collaborations with brands such as Rimowa, IKEA, and Nike. This short-lived undertaking, only twelve months, can be considered a precursor to Off-White, the Milan-based brand Abloh launched in 2013 that helped establish his name in the fashion industry and well beyond it. For instance, under Off-White, officially a fashion brand, he released his Grey Area furniture line in 2016.

Less than a decade after his first visit to Paris Fashion Week, Abloh was appointed artistic director of the menswear collections at Louis Vuitton in 2018. He joined the ranks of Marc Jacobs, who had previously been the creative director at LV, and Kim Jones, Abloh’s friend, mentor, and former style director of LV’s ready-to-wear menswear. Only a year into the role, Abloh learned of his cancer diagnosis and made the decision to keep it private. Coincidentally, that same year, the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago honored Abloh with a mid-career retrospective designed by Rem Koolhaas’s research studio.

The retrospective compiled a comprehensive overview of most of the tangible creative output that Virgil Abloh is celebrated for. Yet, beyond the material things that Abloh created, there is a strong belated case to be made for his immaterial contributions to culture, however defined. While some were influenced by working with Abloh and the entities he founded or worked with, others were influenced by knowing that there was somebody like Abloh – a dark-skinned, young African American – in the plotting sessions of an international luxury label, despite the ambivalent relationship many have with fashion as a material status symbol, and although many would never be able to afford anything Abloh branded or signed off on.

As artistic director at LV, Abloh made work that transcended explicit sales propositions and, in some cases, departed from them altogether. His last campaigns at Louis Vuitton were elaborately collaborative yet self-contained works. They were seemingly designed to dilute their immediate purpose, which is to sell a nebulous idea of luxury while creating demand for things that nobody really needs. Several shows, including the Men’s Fall-Winter 2021 collection, had to be presented online due to the pandemic. Never afraid to alienate LV’s traditional clientele, Abloh left his fingerprint all over the resulting 15-minute presentation, a visually rich manifesto that stands singularly as an episode of his forceful output at LV. Its storytelling is urgent and its thrust decisive. It gets straight to the point. The slightly crowded set and the intentionally capricious movements of the models mirror Abloh’s synergistic and multidirectional vision. Not the kind of designer to let clothes speak for themselves, Abloh delivered a plethora of aesthetic, aural, and visual references that spanned poetry, music, architecture, choreography, and fashion. If Abloh had ever set out to provide us with a glimpse of the essence of his creative process, his last couple of shows succinctly captured what he wanted to say. In Abloh’s own words: “In my mind, I haven’t done any work yet. I’ve just made a case for why my point of view is valid.”

Eric Otieno Sumba is a writer. He is one of the contributors to African Artists: From 1882 to Now (Phaidon, 2021) and is a contributing editor at griotmag.

Image credit: Courtesy of Carpenters Workshop Gallery, photo: Griffin Lipson

Notes

| [1] | From William Martin, “Make the Ordinary Come Alive,” in The Parent’s Tao Te Ching: Ancient Advice for Modern Parents (Cambridge, MA: Da Capo, 1999). |

| [2] | From Anja Saleh, Soon, The Future of Memory (Münster: Edition Assemblage, 2021), 34. |

| [3] | Diane Solway, “Virgil Abloh and His Army of Disruptors: How He Became the King of Social Media Superinfluencers,” W Magazine, April 20, 2017, https://www.wmagazine.com/story/virgil-abloh-off-white-kanye-west-raf-simons. |

| [4] | Adjoa Wiredu, “Generation Can Do,” in On Reflection: Moments, Flight, and Nothing New (London: Jacaranda, 2020), 74. |