Powerlessness as a fount of sexual pleasure was featured prominently in a recent show at the Brooklyn Museum. The first museum retrospective of Jimmy DeSana’s work prominently staged scenes of sexual submission against the backdrop of contemporary philosophical discourses and real-life practices. In all instances, objecthood was exhibited as a state to lust for, as Christian Liclair lays bare in his historical contextualization of “Jimmy DeSana: Submission.” Against the background of this issue’s focus on “Ohnmacht,” Liclair unveils the (con)sensual negotiations of power imbalances during SM as an exercise in questioning dichotomies between powerful and powerless, in order to loosen the restraints of the body’s normative organization and its premeditated capacities for pleasure.

Jimmy DeSana’s photographic work has often been characterized as an exploration of the human body’s objecthood. For Elisabeth Sussman, the artist’s continuous body-object investigations turn people into still lifes. Travis Jeppesen identifies a fluffy comfort, at least for gay audiences, in DeSana’s evocation of becoming-object. And for Jill H. Casid, his late work even positions the viewer as an “object among objects in not the abyss but the immanence of an object world that poses the questions of being.” “Jimmy DeSana: Submission,” the late artist’s recent retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum, even parades objecthood in its catchy title, given that one understands the act of surrendering or yielding to a form of superior authority – the willful denial of autonomy – as a form of objectification. But instead of construing the abdication of bodily sovereignty as something undesirable, the exhibition highlights the pleasures that becoming an object can entail – the residual power that might lie in alleged scenes of powerlessness, in giving in to someone or something else in order to become undone. Ambitious and thoroughly researched, curator Drew Sawyer’s survey of DeSana’s lifework recognizes those aspects throughout his artistic oeuvre, from his senior thesis “101 Nudes” at Georgia State University to his participation in mail art networks, his sexually explicit works, and, finally, his surreal compositions in lurid, vividly illuminated colors. But nowhere does the pleasure of being-object, of unraveling subjectivity, become more apparent than in the mise-en-scènes of sexual submission, which DeSana realized shortly after moving to New York in 1973, eventually – and fittingly – living not far away from Times Square, then the city’s seedy, flourishing red-light district.

Evoking a similar indecency, red light emanates out of a smaller side gallery of the show’s central room, enticing visitors to enter and look at 24 of the 29 photographs that made up DeSana’s self-published book Submission, from 1979. Both the plates in the book and the photographs on the wall mostly show nude, solitary individuals in often exaggerated poses, and they are always named after an object prominently featured in the shot – but never after the sitter. Toilet (1977–78), for example, shows a man squatting in a toilet bowl wearing nothing but a black leather mask. The same disguise is used on a bare-chested woman in Jockstrap (1977–78), though it is also accessorized by the photo’s titular undergarment, initially invented to protect the genitals during contact sport but used here to fasten a dildo as an extension of the nose. And for Masking Tape (1977–78), DeSana swathed a man’s body in painter’s tape, leaving only his feet, hands, nipples, nostrils, and penis exposed and unprotected.

As one can plainly see, these scenes are reminiscent of what might be subsumed under the acronym SM, an umbrella term characterizing a variety of erotic practices between consenting partners that act out a temporary exchange of unequal power relations. To incorporate such elements or scenes was certainly not uncommon for (gay) artists in New York during the 1970s, as has been demonstrated in recent years by exhibitions of Alvin Baltrop, Nancy Grossman, and, of course, Robert Mapplethorpe – who famously staged SM scenes in his X Portfolio, which was first shown at Robert Miller Gallery in 1979. But also beyond New York’s burgeoning (and not rarely scandalous) downtown art scene of the 1970s, the practice of eroticized power imbalances was an increasingly visible force to be reckoned with. Coinciding with the rampant rise of sex-related businesses in the United States and the proliferation of commercial pornography since the late 1960s, SM became a central issue, or the manifestation of a larger problem, not only for contemporary feminists, psychoanalysts, and the media but also for philosophers, who ennobled the pain-enduring, submissive masochist as a potent figure for radically reconsidering psychoanalytical mechanisms of (sexual) subjectification and subjecthood. By incorporating ephemera as well as books and interviews from this time, Sawyer’s show differs from the previously mentioned retrospectives devoted to artists who were (at least partially) bound up with SM and invites visitors to contextualize (sexual) submission in relation to DeSana’s medium as well as within contemporaneous artistic and philosophical discourses. But it highlights, too, that powerlessness in this context was first and foremost erotic, which means that it was a set of practices geared toward the creation or intensification of “real” corporeal pleasures.

The center of the room, between portraits of (dressed) underground royalty such as Debbie Harry, Kathy Acker, and Laurie Anderson to one side and the alluringly shimmering side gallery to the other, is occupied by several display cases filled with manuscripts, books, and journals from the late 1970s and early 1980s. A selection of these and other more recent publications are also featured in a reading corner at the end of the exhibition; among them, for instance, the “Schizo-Culture” issue of Sylvère Lotringer’s journal Semiotext(e), from 1978, which gathers an illustrious group of artists and writers such as Michel Foucault, Kathy Acker, Ulrike Meinhof, and Jack Smith, as well as DeSana. In it, DeSana’s photograph Masking Tape illustrates an essay by Guy Hocquenghem, who urges his gay readers to cultivate alternative modes of belonging and kinship instead of succumbing to sexual normativity and respectability politics, an assimilation in which even “sado-masochism itself is no longer more than a vestiary fashion for the proper queen.”

Three years later, masochism would play a pivotal role in Semiotext(e)’s “Polysexuality” issue, which is also presented in one of the display cases but unfortunately not on the shelf of the exhibition’s reading corner, although it is key to understanding the philosophical discussions valorizing SM that might have influenced DeSana’s artistic practice. Guest-edited by François Peraldi and graced by a leather-clad biker on its cover, this anthology’s contributors seek ways of subverting binarisms and the “biological opposition of sexes” by advocating for other modes of corporeal pleasures. It also features “November 28, 1947: How Do You Make Yourself a Body without Organs?,” a translated chapter from Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s book A Thousand Plateaus, which had just been published in French the previous year. In it, they portray the masochistic body as one epitome of their quest “to propose a new concept of desire,” instead of approaching the masochist’s submission as symptomatic of an unconscious association of physical pain with pleasure resulting from arrested infantile development, as Freudian psychoanalysis has been preaching for many decades. For Deleuze und Guattari, the masochist finds new ways of connecting with others beyond the body’s traditional genital orientation associated with the Oedipal triangle and instead “uses suffering as a way of constituting a body without organs,” which is occupied only by intensities that pass through: the body becomes nothing more than a pure event. Quite similar, then, is Peraldi’s definition of polysexuality as an infinitively diversified sexuality that “desubjectifies” the body and expands its capacities for corporeal pleasure from the so-called sexual organs. Here, Peraldi surely references Foucault’s anti-identitarian demand to make use of every part of the body as a sexual object, which Foucault saw actualized in the manifold erotic practices associated with SM, which use the body as a “place for the production of extraordinarily polymorphous pleasures, detached from the valorizations of sex and particularly the male sex.” The concept of pleasure is important for Foucault because, unlike earlier psychoanalytical notions of desire, it is not attached to the subject. Experiencing pleasure is, according to him, “ultimately […] nothing other than an event, an event that happens, that happens, I would say, outside the subject, or at the limit of the subject, or between two subjects.”

While Foucault was anything but a merely passive observer and philosopher of kinky encounters himself – he was, reportedly, a patron at New York’s infamous men-only sex club the Mineshaft – Peraldi’s anthology deliberately included more hands-on, so to speak, approaches to the topic of sexual submission as well. Under the title “Coprophagy and Urinology,” “Polysexuality” features an essay by the New York pro-domme Terence Sellers, which would later become part of her book The Correct Sadist (1983), displayed nearby, which was a sort of SM etiquette manual as told in the voice of Sellers’s alter ego, Angel Stern. It is salient that Sellers takes a central role in the Brooklyn Museum’s retrospective of DeSana; on a wall opposite the table display of The Correct Sadist, Sawyer mounted a video of a 15-minute interview between Lotringer and the professional dominatrix next to a series of photographs labeled Dungeon Series (1978–79), which the curator attributed not just to DeSana but to Sellers as well. The ten images from the series (more were shown at the simultaneous exhibition “Jimmy DeSana: The Dungeon Series, 1978–79” at PPOW in Manhattan) capture clients of Sellers in often demeaning postures. One untitled photograph centers a naked man, hooded and handcuffed to a tree in the woods, with wooden clothespins hanging, in the front, from his nipples and stretching his skin toward the sides of the picture. Sellers’s arms enter the image from the left; she is wearing shiny black leather gloves and, presumably, clipping more of those misappropriated household items onto his body for tortuous intent. In another picture in the series, Sellers’s leather-gloved arms penetrate the photograph from the upper left, holding a razor blade in the right hand while the other is grabbing a man’s penis and scrotum, which are studded with droplets of blood. And while this scene most certainly looks painful to visitors of the exhibitions, the dripping of a different bodily fluid leaking from the tip of the man’s penis is indicative of the pleasure he is evidently gaining from this perforation of his skin.

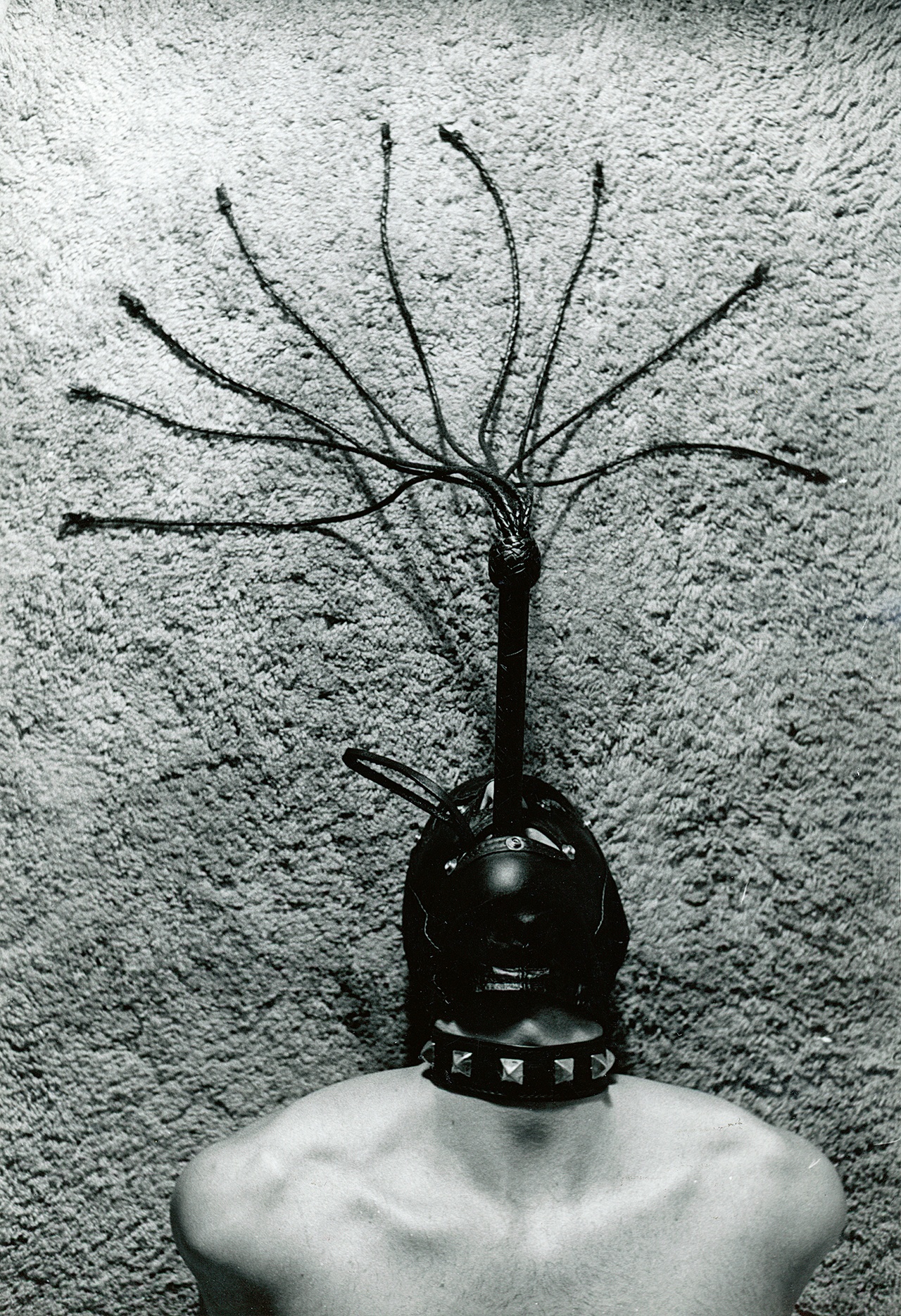

These photographs, as we learn from the wall text, were likely supposed to illustrate Sellers’s publication Correct Sadist. It seems fitting, then, given that the book seemingly ranges between documentary and fictionalized accounts, that the images Sawyer selected from DeSana’s and Sellers’s cooperation oscillate between diligent compositions – like the photograph of a multi-tailed whip whose coriaceous handle rises out of the mouth of an anonymous human figure while the whip’s nine braided thongs are arranged in a half circle to resemble rays of a rising sun against the background of a fluffy carpeted floor – and images that, not least due to their abrupt cropping, are reminiscent of snapshots and thus evoke a documentary, voyeuristic aesthetic.

Thus, the figures in the Dungeon Series seem to be objectified and powerless in two ways: they are subjected not only to Sellers’s power as a dominatrix but also to the camera’s gaze and are therefore, by extension, exposed to the intrusive eyes of an art audience. However, this simple opposition between subject and object, active and passive, powerful and powerless misconstrues the residual agency of the submissive, which, paradoxically, lies exactly in its abdication. Take Sellers’s own account: years later, she mentioned that she called DeSana whenever a client of hers was open to being photographed and that these sessions “were subject to whatever that slave’s interest might be, and those particular needs would determine the material of the shoot for the evening.” Hence, this aspect of interdependency and cooperation of the photoshoot correlates with the interaction of a SM scene: even if it seems like one person has no agency and is subjected to exposure, the scene is actually the result of a previous agreement on individual preferences, limits, and bodily capabilities that is based on mutual respect and consent. What unfolds is an ambivalent scenario that is at the same time regulated and open, staged but with real material consequences: be they bodily perforations or ejaculations.

In an intimate article written for The Advocate in 1979, P. Califia, an active sadomasochist and one of the founders of the lesbian SM advocacy group Samois (whose anthology on SM titled Coming to Power is rightfully included in the exhibition’s library), emphasizes the impermanence of the roles of dominant or submissive, which are not acted out to gain any sort of ideological and social leverage or because of any sense of (natural) entitlement but solely in the context and for the sake of momentary gratification generated in synergy with other bodies, body parts, or inanimate objects. The images in the show attest to the fact that bodies can be organized differently in processes that are creative and communal, thereby revealing the fundamentally historical contingency and relationality of their constitution. As a transgression of bodily integrity and sexual self-sufficiency, SM causes what Foucault has described as an “anarchizing of the body, in which hierarchies, localizations and designations, organicity if you like, is becoming undone. […] It’s the body made entirely malleable by pleasure: something that opens itself, tightens, palpitates, beats, gapes.”

Califia, however, reviewing The Correct Sadist upon its 1983 publication, criticizes Sellers’s obsession with “correct” SM: “No matter how serious a scene is,” Califia explains from personal experiences, “I never lose my awareness that I’m dressed up in funny clothes, saying absurd things […]. It’s wiser to laugh at yourself and let them laugh, too – then stomp across the room and wallop them.” DeSana, having stopped collaborating with Sellers to pursue his own publication, seems to be leaning into said absurdity. As previously mentioned, the images from the Submission series depart from the earlier snapshot aesthetic to foreground bizarre bodily configurations under dramatic lighting. In Refrigerator (1977–78), for instance, we find a woman dressed in lingerie, hands and ankles in bondage, crouching inside an opened refrigerator while two eggs are placed between her upper leg and abdomen. The dramatic staging of the photographs included in the red-lit room invite us ultimately to consider the mediatedness inherent in all photography. At the same time, the posing and staginess of the Submission series productively correspond to what the art historian Richard Meyer once called the “intrinsic theatricality” at the heart of SM, which manifests in the premeditation that precedes it, the temporal imitation of roles that goes along with its performance, and, certainly, the proclivity to particular costumes – or “funny clothes,” as Califia would have it. The tension between staged and real, in photography as well as in SM, is further highlighted by the lighting concept that Sawyer chose to set Submission apart. Although the steady red light significantly distorts the way the photographs are perceived, it is explained as a homage to the “File 13” show organized by Sur Rodney in 1978, which featured DeSana among others and used red lights to recall the safelight used in a photographer’s darkroom. But, needless to say, one is reminded of another sort of darkroom here as well, in which the atmosphere of twilight and secrecy evoked by red light is desired for real-life encounters.

However, the previously mentioned aspect of transgression, of getting to feel one’s own body differently, is also, somehow, mirrored in the way the monochrome lighting engages the viewers, subjecting them, unwittingly, to corporeal affectations whose material consequences they have no control over but that can be felt when leaving the seclusion of the Submission room. Based on neural adaptations in the brain that, interestingly enough, function similarly to color balance adjustments in photography, one’s vision is haunted by short-lived green afterimages that gleam over one’s perception of the exhibition before fading out. Perhaps unintentionally, this effect further serves to highlight human situatedness in relational and interpersonal terms, as it permeates the exhibition: Submission imagines an empowered subject in the twilight between powerful and powerless, a subject that is never fully settled or simply present as a sovereign self but that instead emphasizes the fluffy comfort and profound beauty of becoming an object among objects in an object world.

“Jimmy DeSana: Submission,” Brooklyn Museum, New York, November 11, 2022–April 16, 2023.

Christian Liclair is an art historian and critic as well as the editor-in-chief of TEXTE ZUR KUNST.

Image credit: 1. © Brooklyn Museum; 2 + 3. Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, © Estate of Jimmy DeSana, photo Allen Phillips

Notes