CONTEMPORARY SUBJECTS OF HISTORY Julia Gelshorn on “Gerhard Richter: Painting after the Subject of History” by Benjamin H. D. Buchloh

Gerhard Richter, “Blumenstrauß,” 2009

Art history revisits itself – not only in Gerhard Richter’s oeuvre, which now spans more than half a century, but also in how this oeuvre is revisited in a long-anticipated, comprehensive study by Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, which is based on more than 20 years of essays. These are now compiled for the first time, partly revised and reframed by additional chapters. Painting after the Subject of History starts at the origins of Richter’s career under the Communist regime of the German Democratic Republic and ends with Richter’s latest “documents of barbarism” in the acclaimed Birkenau cycle from 2014. It also includes further essays on the grisaille paintings, the revival of traditional genres, the ongoing photography project of the Atlas, the different series of abstract paintings, the glass panels, the window in the Cologne Cathedral (2007), and Richter’s drawings. It is well known that Buchloh has accompanied Richter’s complex production through what turned out to be a constant negotiation between two at times antagonistic positions.

Buchloh has always taken up the challenge of understanding Richter’s seemingly conservative turns as provocations of the author’s own ideological dogmas. Precisely because of the contradictory nature of the various phases of Richter’s work, Buchloh considers him “the exemplary painter of the ‘dialectic of enlightenment,’ Theodor W. Adorno and Max Horkheimer’s key philosophical text of the post-World War II period” (xxv). Like all of his writings, his dialectical understanding of the much-discussed heterogeneity of Richter’s oeuvre in the context of the totalitarian regimes of Stalinist Socialism in the GDR, on the one side, and of the all-encompassing consumer culture of the West, on the other, has been shaped by critical theory. Yet what is new in Painting after the Subject of History is its historical synopsis, which now intertwines the life’s work of Richter with that of Buchloh. The retrospective view enables Buchloh to identify historical “work phases” and “key works” in what Richter has strategically presented as a constant and seemingly random proliferation of contradictory concepts. [1]

Thus the “divided subject” Gerhard Richter, which has been at the center of Buchloh’s studies from the very beginning, now becomes even more tangible via the prehistory of his early work: by juxtaposing Richter’s first Socialist Realist paintings with the almost abstract monotype series Elbe (1957), Buchloh identifies, already before the official career of Richter, all sorts of “dialectical inversions.” [2] In the chapters that follow, those dialectical inversions between deskilling and reskilling, between referential and semiotic uses of photography, between regressive and progressive modes of painting, between rational and irrational concepts of abstraction, and between affirmative sentimentality and critical subversion are historicized as artistic expressions of historical repression and denial and as a simultaneous mnemonic approach of the “subject” Richter to his historical “subjects.” Gerhard Richter: Painting after the Subject of History therefore ambiguously refers to two (im)possibilities of the subject: the depicted but unrepresentable subject matter and the idea of subjectivity, invalidated as much by the apparatus of German fascism as by the postwar culture industry. As Harmon Siegel has shown in his review in Artforum, the subtitle of this book also alludes to different meanings of “after”: painting “in the aftermath” of subjectivity and subject matter but, at the same time, painting still “chasing after” the subject in images “after” photography and in the ongoing search for memory images malgré tout. [3]

Research on Richter by other authors is largely absent from Buchloh’s footnotes, except for references to a very few early articles. It appears sometimes indirectly, when Buchloh summarizes or mentions the broad debates on particular groups of works. And for those familiar with the field, this research literature also appears indirectly in that it is part of the historical background against which Buchloh revisits, and in part revises, his own positions. He responds not only to developments in Richter’s oeuvre but also – tacitly – to the art-critical positions that have developed in relation to it in the meantime. It is Buchloh’s revision of his then-contemporary readings of Richter, which now have already become historical, that is so fundamental to this book. Contrary to his historical readings that developed close in time to the artist’s production, his current readings are now based on knowledge of Richter’s oeuvre as a whole.

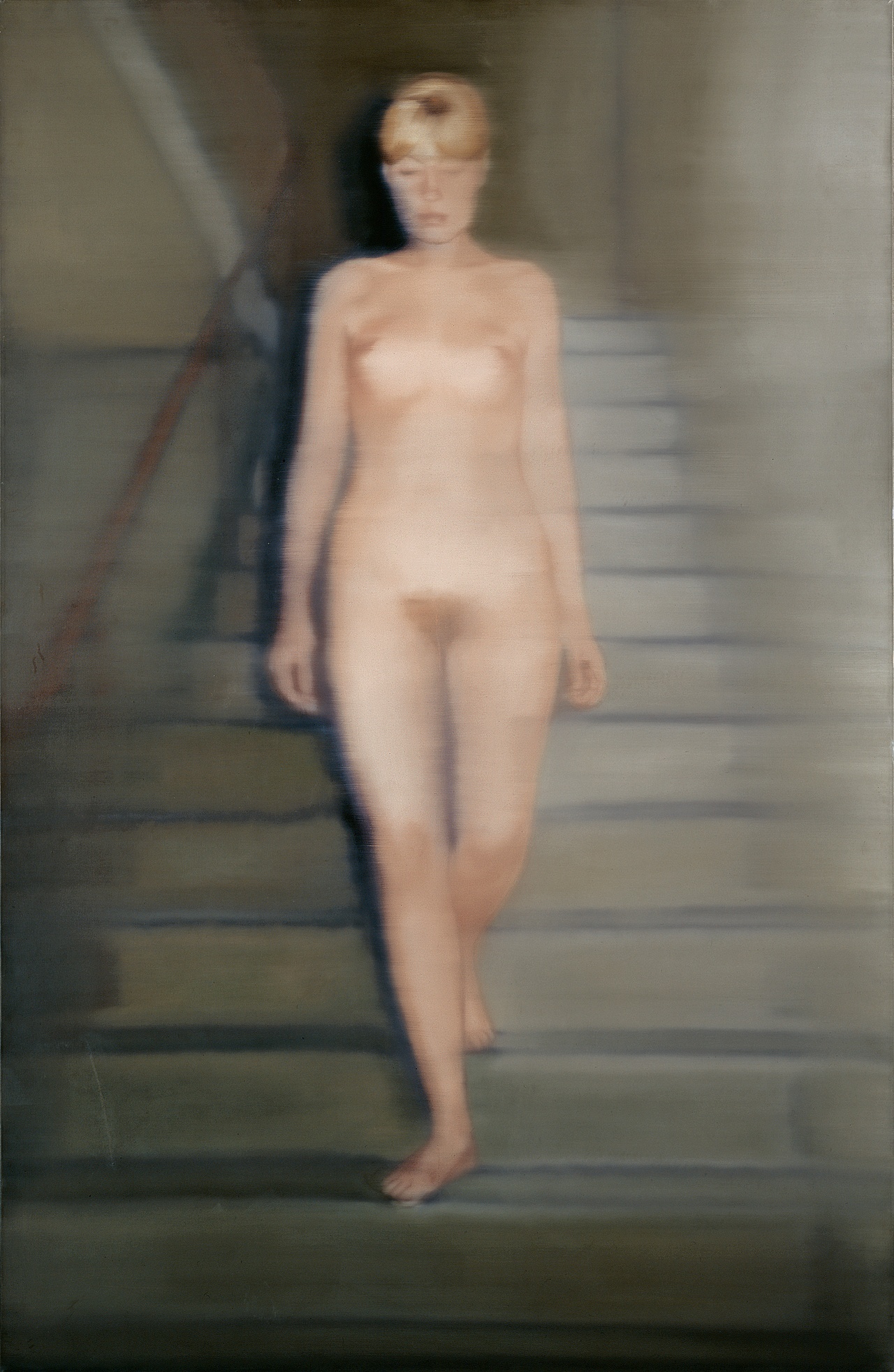

Gerhard Richter, “Ema (Akt auf einer Treppe),” 1966

Thus, for example, in the analysis of Richter’s Ema (Akt auf einer Treppe) (1966), the “reactionary elegic quality” that Buchloh analyzed in 1993 as “practically untenable ambivalence” between the historical avant-garde (through the title’s reference to Marcel Duchamp), the spectacularized nude painting of the neo-avant-garde (in turning away from Yves Klein and from Pop), and the neoclassicism of the “specifically German, National Socialist and Socialist realisms” is now defined to be the starting point of a “second phase” of Richter’s work. [4] While in 1993 Buchloh had concluded that the classical genre could not be revived, he now admits that with Ema, “the artist reclaims a vastly different historical horizon for the individual and collective scope of painterly commemoration: the horizon of the history of painting as much as the horizon of a reemerging presence of desire and erotic mimesis after mourning” (129). This reevaluation of Ema as the integration of “a new mnemonic dimension” that transfers the project of mourning painting’s impossibilities “to a larger psychological, epistemological, and aesthetic framework” (129) is only possible (and necessary) against the background of the whole group of provokingly conservative family pictures Richter produced since 1993. This group of paintings is discussed in the following chapter, which opens with a motto by Carl Einstein. He locates Pablo Picasso’s search for truth and plenitude precisely in the “tensions between simultaneous opposites, refusing to obey the dogmatic demands of a singular style” (131). Bearing in mind Buchloh’s earlier radical condemnation of the regressive return around 1920 of male avant-garde artists (such as Picasso) to reactionary and authoritarian realisms, his affirmative Einstein quotation – and, hence, his cautious rehabilitation of Picasso’s neoclassicism after Cubism – comes as a surprise. [5] This being said, it makes sense in the context of Buchloh’s reframing of a similar retour à l’ordre in Richter’s work: Buchloh now reads Richter’s almost shockingly intimate group of family portraits as critical resistance. He argues that in the exceptional use of a seemingly obsolete genre, the artist turned away from contemporary forms of deskilling, which had become repetitive and spectacularized, thus enabling a new form of “countermemory.” It must not pass unnoticed that in the process of this argumentation, Buchloh radically undermines, and quite consciously so, the set of criteria advocated in his own previous criticism.

What makes this transformation of essays into chapters so valuable is exactly the fact that this book is not just a selection of Buchloh’s “best of,” nor is it a belated assembly of dispersed articles: on the contrary, it is the documentation of a historical interaction of artistic production and art-critical reception in a self-reflexive process. [6] Buchloh thereby impressively demonstrates the extent to which the art-critical position is subject to the same mechanisms of ideological domination and oppression that he brings to bear on the analysis of the artist’s oeuvre:

If I venerated Bertolt Brecht and John Heartfield as the heroes of a radical progressive Weimar culture and as the rare exemplary figures of German antifascism, Richter could only consider them as the historically corrupted members of a ruling cultural elite, the bête noirs of an opportunistic assimilation of a former radical left culture to post-World War II Stalinist state socialism. (xvii)

Buchloh thus clearly reveals his own historical situatedness as well as the “duality” of the “shared and yet also utterly different sociohistorical formations” of artist and critic:

While we are separated by a decade of generational difference, we were both fundamentally defined by one of the most formative conditions, namely having been born in fascist Germany, and having grown up in the two mutually exclusive yet also deeply intertwined postfascist successor states of a communist East and a capitalist West. (xvi)

The art critic could not be more explicit about the fact that, for him, writing “after the subject of history,” just as much as painting, necessarily means understanding oneself as a subject of history. Buchloh has shaped this history of Richter’s oeuvre over the years. His book is the claim not only to historicize this position itself but also to reflect self-critically on the historicity of his position and the one of the artist. Therein lies its quality.

Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, Gerhard Richter: Painting after the Subject of History, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2022, 696 pages.

Julia Gelshorn is a professor of modern and contemporary art history at the Université de Fribourg, Switzerland. She has published on modern and contemporary art with a focus on strategies of appropriation and repetition, on artists’ writings and interviews, on new realisms, and on French art and theories of grace in the 18th century. She is currently leading the SNSF project “Real Abstractions. Reconsidering Realism’s Role for the Present.”

Image credit: © Gerhard Richter 2023

Notes

| [1] | Here, Buchloh follows a tendency that has manifested itself for some time in Richter research. See Julia Gelshorn, “The Reception of History and the History of Reception. On the Contemporaneity of Gerhard Richter,” trans. Claudia Heide, Art in Translation 4, no. 2 (2012): 185–210. However, Buchloh is less interested in the “life” of the artist than in the social determination of form in Richter’s work in its various “phases.” |

| [2] | On the “divided subject,” see Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, “Gerhard Richter: Painting after the Subject of History” (PhD diss., City University of New York, 1994), xi–xii. It is significant that Buchloh reuses the title of his earlier dissertation – ultimately, he presents his study as the completion of his own examination of an artist’s life’s work. |

| [3] | Harmon Siegel, “Quondam Theory,” review of “Gerhard Richter: Painting after the Subject of History,” by Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, Artforum 61, no. 6 (February 2023). Here, I am alluding to Georges Didi-Huberman, Images malgré tout (Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 2003), a study on four photographs that had secretly been taken in August 1944 by a prisoner at Auschwitz and that the author discusses “in spite of all” prohibition of images of the Holocaust. The study had actually triggered Richter’s work on the Birkenau cycle. |

| [4] | Benjamin Buchloh, “Ema (1966) oder ein Akt in der Neo-Avantgarde,” in Gerhard Richter, vol. 2, Textband, ed. Angelika Thill, exh. cat. (Ostfildern-Ruit: Cantz, 1993), 19–27. |

| [5] | See Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, “Figures of Authority, Ciphers of Regression: Notes on the Return of Representation,” October, no. 16 (Spring 1981): 39–69. |

| [6] | For an earlier discussion of this dynamic, see Gelshorn, “The Reception of History and the History of Reception,” 185–210. |