TAKING GOD RIGHT UP YOUR ASS Bruce Hainley on “Nicolas Pages” by Guillaume Dustan

Guillaume Dustan in Tahiti, 1994

Guillaume Dustan took pride in his blow-job skills:

If I am one of the best cocksuckers in Paris, it’s because I know how to do it. I start off by letting the dick get hard by itself by offering no resistance around it, I deep throat it, and after I come back hard to work the whole shaft, I suck the head while at the same time placing my hand around the balls, pulling them downward without pinching, I swallow one and then the other and then both at the same time and then I just eat them, I chew them, almost biting without actually biting, and then I go back to work on the dick and usually it’s not long until the guy is crying out for his mother and exploding. [1]

Trespassing any supposed cordon sanitaire between “fiction” and “nonfiction,” Dustan wrote Nicolas Pages to operate, in part, as fag Kama Sutra and theoretical minaudière for any stray item or thought that he clocked, from grocery items (“Newman’s Own vinaigrette”) to philosophical digressions (“WHAT IS THE PURPOSE OF A NIGHTCLUB?”). Made up of (reworked?) diary entries, five articles for the gay glossy Têtu that an editor rejected, (drafts of?) novels within the novel – The Story of Rabbit and Little Bear and How I Became (Almost) Perfect – and a hilariously amazing glossary (“Act-Up: Anti-AIDS and pro–sick people activist movement […]”), the book misbehaves as street ethics and intellectual cum dump. By moving away from the “trap” of the ideological command to “write well,” Dustan deep throats it all to genre-explosion and to “writing life.” Tutelary spirit Marguerite Duras raises her glass approvingly (“Duras: Writing license”), since his methods entail nothing naïf or straightforwardly mimetic, in part because nothing about the actual is straightforward, or straight. “Nicolas is real,” yes, but also, as Dustan writes more than once after certain accounts, “actually that’s not [at all] how it happened”; he revises the actual to tell a tale, then swaps it for another tail, barebacking the real, really.

Let’s not too quickly lose track of the novel’s how-to energy: how to live, how to fuck, how to write a novel, how to revel in language and its histories, sense, and nonsense. Dustan privileges know-how to figure out what knowing in the zones of desire means and how it feels.

The only authorized technical discourse around sex seems to be that of the whore. It would be difficult indeed to deny that the whore is a professional. And to say professional implies professionalism, and therefore technical skill. But I haven’t whored myself out enough to be able to boast of this type of experience. I’ll just say like Madonna in one of Erotica’s remixes: I’m a love technician.

In his work as founding editor of Le Rayon Gay (for Éditions Balland), Dustan proposed a rowdy gay pride parade of writing, from translations of Gregg Araki’s and Bruce LaBruce’s film scripts to the The Leatherman’s Handbook. The love technician, sybarite and sometime size queen, looked to the pornstar and pornstar-as-writer (Aiden Shaw) to train the literary to take in as much as it can – a kind of rhetorical foot-fucking in keeping with the full range of Dustan’s sexual practices (some of which he filmed); he understood that porn – not merely something like a multi-billion-dollar NGO (now much of it complicatedly “privatized” on socials) – presents a cultural gay history that requires working-through, since it mirrors Hollywood and/or TikTok and/or global media’s daytime rapacities. Via the pharmacopornographic [2] was just one way Dustan declassified the literary, a ruthlessly democratic project that still weirdly allowed him to disdain the ugly, back up his judgments with legal acumen (before coming out as a writer and gay radical who balked at so much of the dogma in the first wave of AIDS, he worked as an administrative judge for years), and eventually turn to making films (a tag-teaming to expand writing’s capacities). “French bourgeois literature is so comprehensively based upon the aristocratic values of distinction*,” he argued, “that it has the greatest difficulty in creating a modern literature. Saint Marguerite pray for our sins.” He would probably gag at the premise that he put Jacques Derrida’s il n’y a pas de hors-texte to the test – no grapheme and shiver, no murmur, blankness, and silence that might not matter – and throw a copy of La vie matérielle across the room so it hit me smack in the face. He channeled the self to find its abolition.

This is the value of all the whole apparently narcissistic tendency in contemporary art: to take oneself as one’s subject is to also explode the stupid dichotomy between the artist and nonartist. To show that there are only people who work. On themselves. It’s obviously not a coincidence that this stuff is practiced by faggots and dykes and female feminists more than by Catholic heterosexual men. As Hegel said, the master does not need to work. He becomes stupid. It’s the slave who ultimately triumphs. Dialectical reversal.

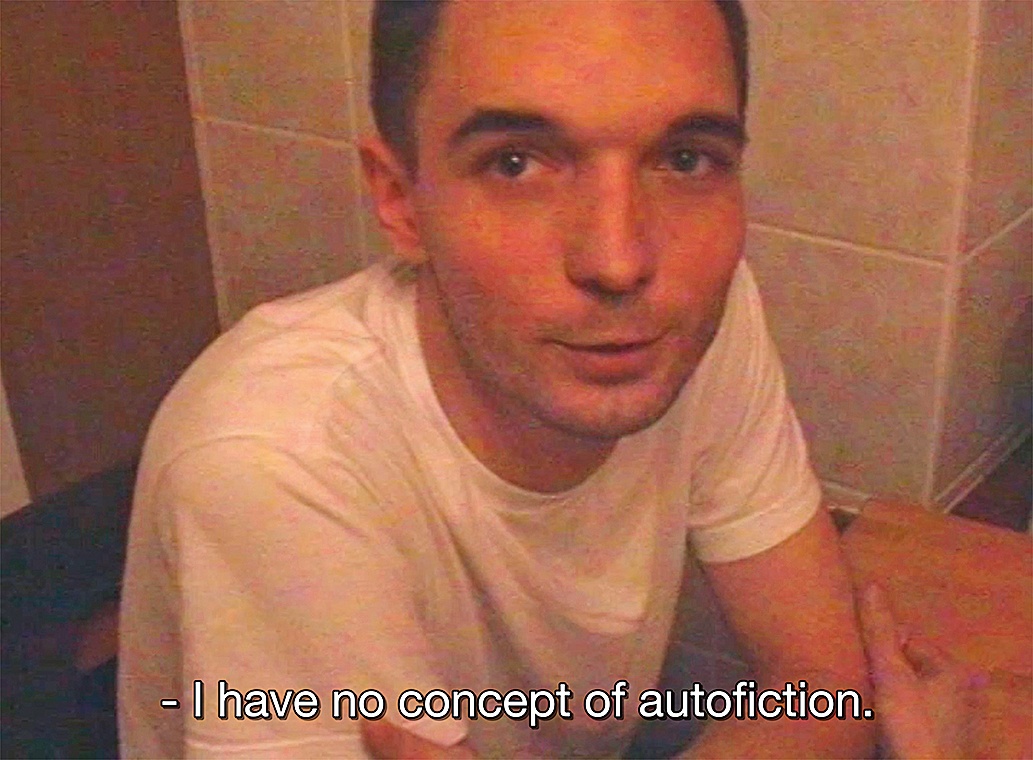

Guillaume Dustan, “Nous (love no end),” 2000, video still

In Nicolas Pages there are many pages and there’s more than one Nicolas – Nicolas Pages as distinguished from Nicolas Milon – so Dustan, to clarify, must write out “Nicolas Pages” again and again, crush-like. Nicolas Pages is a young Swiss writer, “a blonde with blue eyes,” his first novel, Je mange un oeuf, “the most important book since […] American Psycho,” Dustan confesses. Pages as in the pages things are written on, pages that come to make up a book, pages read that assemble to be Nicolas Pages, “novel” as booty call and joyride. Dustan is figuring something out about desire, how men come together in various ways and how to write such coming: to negotiate what it meant to be an HIV+ fag at the end of the last millennium, before everything changed by going online, time and distance abolished.

We have the right to state the obvious when the obvious is not obvious to everyone. And even more so when the obvious is not popular, when if we have the misfortune of being born in say, Afghanistan, having this kind of desire means having a good chance of ending up crushed under a wall.

I started to think that the late 1990s might be the last moment when fags actually read books. Didn’t bookish use to be a euphemism (not a totally bad one) for faggy? Didn’t an interest in art and/or dance and/or reading use to signify (especially when the various “hankie codes” of queer desire might be beyond one’s ken) or at least drop some hairpins about one’s availability or curiosity, even if (especially if) not known by the one dropping them? When one’s thirst signified before one understood how to express it. (Shrug emoji) Culture – top to bottom, bottom and top – not merely as a way to see oneself simply reflected or reiterated or reified but to excite one’s difference, to slip into another life, another language, another vocabulary, inflection, another way of being, another way of living, defamiliarly, defamilially. All action, almost anonymously, all bodiliness, no personhood except as actions perform or become it. No automatic “likes.” Interpellating one’s sense of self into and being interpellated by cultural texts that seemingly had no inkling of or space for you, that perhaps even scared you.

Dustan aimed for the mutant, believed in the mutant, and Nicolas Pages sublimes as a mutant text. “Man is mutant: language mutates, tools / are becoming more and more powerful / man dreams himself up.” With every “tech” available – drugs to house beats – “he” fucks himself up, l’éducation sentimentale.

Homosexuality is in structural terms a pédégogie; a faggot further education; from N, I learned about Le Renu, about store-bought crème caramel, house loops; from P, tequila-champagne, and getting high on poppers; from E, Madécassol cream; from ;;;;. The multiplicity of lovers multiplies the knowledge of things, of their mutations: of technology in general and of accompanying technology in particular (Batman- or Bond-style): drugs, sex gadgets, cell phones, faxes, chewing gum, car, plane – soon techno-genetics will really transform us into bionic mutants (athletes are already transformed by anabolic steroids, artists by psychotropic drugs), that plus genetic eugenics: we’ll be like gods and we’ll be able to make babies using two ovules or two sperm cells, or make little clones.

Nicolas Pages is a relentless text, sex toy to be enjoyed, manifesto to be argued with. I was going to complain (what or where is anything like it in fag or queer culture now – able to zip-zap from RuPaul to Duras, from Wonderbread and Ecstasy: The Life and Times of Joey Stefano to Michel Foucault, something worth being both excited and pissed off by, excited because pissed off), but I care only that people take it like a hit of Ecstasy or a bump of whatever, dealer’s choice, to demand more, demand smarter, and write with Dustan’s spirit, his no-fucks-given flair. Telling tales, abandoning narrative, snapping back into focus, delivering a transcription of his dead grandmother’s “red notebook” or a definition from a 1906 slang dictionary, because one can, because thinking is an embodied pleasure:

To be buzzed, to be boozy. The first degree of drunkenness. The other degrees are: elevated, on, primed, oiled, on the lash, tender, gay, muddled, blotto, lit, hoisted, screwed, tipsy. To be on the ran-tan, on the re-raw, to be decked out. To be tight, lapping the gutter, in a fog, up a pole, loaded, ploughed, full, stuffed, round, lushy, beery. To be sewed up, top heavy, canned, stewed, out for the count, to be drunk as ten men, etc. Dictionnaire d’argot et des principales locutions populaires, by Jean La Rue, preceded by Une Histoire de l’argot, by Clement Casciani, Paris, Librairie E. Flammarion, 1906.

In Dustan’s loaded pursuit of life and its materials, he shot for a text vibe that was “after Harlequin with big dildos, bareback Barbara Cartland,” not just wanly to “create change” but, given what he saw around him, to articulate destruction. Super-high on hash and alcohol, he seethes that he wants “to destroy the social order.” Our judge’s “legitimate self-defense” would be the world he and so many others have been made to endure and survive.

Constance Debré, Wayne Koestenbaum, and Paul B. Preciado are some of the few who grab the experimental baton of all Dustan expected writing-life to be. Testo Junkie, that ferocious keening for Dustan, begins with Preciado learning from a mutual friend that Dustan had just died:

You rotted for two days in the same position in which you had fallen. It’s better like that. No one came to bother you. They left you alone with your body, the time necessary for abandoning in peace all that misery. [3]

The very same day, Preciado takes his first dose of Testogel to “write this book … to avenge your death.” [4]

Dustan wrote his book, for all its rage and passion, also to affirm the quiet moments and soft possibilities of things gently erotic: “I get up, I take a sniff of Nicolas’s pants then slip them on … I’m in his smell.”

Guillaume Dustan, Nicolas Pages, Los Angeles, Semiotext(e), 2023, 424 pages.

Bruce Hainley edited Gary Indiana’s Vile Days: The Village Voice Art Columns, 1985–1988 (Semiotext(e), 2018) and is the author of, most recently, Really, No Biggie.

Image credit: Courtesy of the Estate of Guillaume Dustan

Notes

| [1] | Unless otherwise noted, this and all other quotations are taken from Guillaume Dustan, Nicolas Pages, trans. James Horton and Peter Valente (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2023). Formatting appears as in the original. |

| [2] | See Paul B. Preciado, Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era, trans. Bruce Berdesen (New York: Feminist Press, 2013). |

| [3] | Ibid., 15. |

| [4] | Ibid., 16. |