LUST, KINK, AND THE EMANCIPATORY POTENTIAL OF BDSM Roundtable between Michelle Handelman, Angelo Madsen Minax, and Sami Schalk, moderated by Jill H. Casid

Michelle Handelman, “Hustlers & Empires,” 2018, production still

Jill H. Casid: I want to start us off with our practice, since we’re coming together as artists and practitioners of one sort or another – whether that’s via film, installation, performance, collaboration, writing, or theory as a practice. To get into the space of pleasure with each other, let’s do a round in which each of you speak to the role of pleasure, lust, BDSM, kink, and how you understand that in your new or current work.

Sami Schalk: I recently started a new project studying pleasure spaces for multiply marginalized people. I’ve been interviewing the organizers of these spaces, and over the summer, attending some of the events and speaking to attendees. This research comes out of my work in pleasure activism outside of academic spaces and the desire to develop an understanding about why these spaces matter socially and politically. It’s been interesting to begin this work and talk to people who are organizing spaces for queer people of color or kinky disabled folks and how they’re sustaining these spaces with intention. Additionally, in my artistic work, I have been doing both collaborative and self-photography work that I’ve been calling pleasure art – art that creates and/or depicts pleasurable experiences.

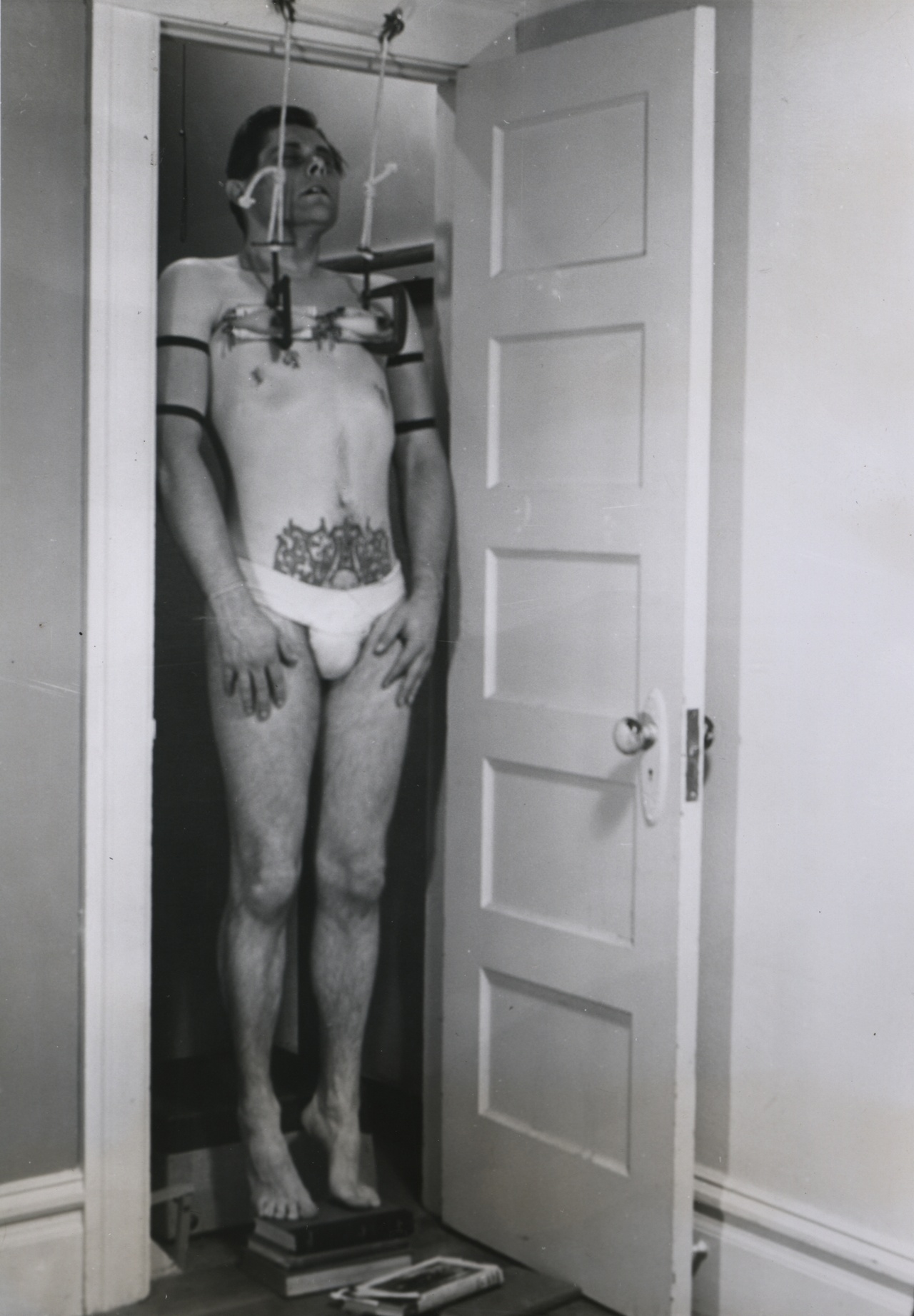

Angelo Madsen Minax: I come from a kind of mixed background in music, visual art, writing, and random projects. Right now I’m working on a film that’s also an exhibition about Fakir Musafar, who was a body modifier, amateur philosopher, a self-proclaimed shaman, photographer, and a performance artist who led an amazing life and was also a person of nonbinary gender identity. But he called it “between the cracks” and used extreme forms of body modification like tight lacing, corsetry, and casting, actually plaster casting to restrict and remold the body. He’s also one of the three people responsible for bringing body modification as we know it to the West – you know, this idea that you can go into a shop and get a piercing or a tattoo. But he was very opposed to the actual industry of piercing and tattooing because of his belief that this was a ritual practice done for magical reasons and with intention. So he built out a whole philosophy, where he borrowed from other cultures, like Sufi mysticism, a lot from Hindu philosophy and religion, the Christian saints, Pagan traditions, Indigenous American traditions – and he was able to cobble these together sometimes in deeply meaningful ways that transcended what they were and became something else altogether. And sometimes not – like, really culturally appropriative or reductive stuff.

Fakir Musafar, “Untitled (Self Portrait with C-Clamps),” ca. 1975

The core group of folks engaging in these practices in the 1970s started this group called Black Leather Wings, which was an offshoot of the Radical Faeries. The Faeries were not quite on board with all of the intense sex practices that these guys were doing. And so they developed this offshoot, wherein you could have the sort of Faerie sensibilities – the communal practice, the magic – and also have hard SM. Ganymede, a person I’m working with, describes it as this big process with the Fairies to break down the ways in which SM is actually a deep practice of loving each other and calls in those damages as opposed to sort of attempting to ignore damages. Of course, different projects you’re working on make you go in different directions with your ideas and what you’re thinking through. I feel like at this point, I’m not thinking about pleasure so much … I tend to come to these ideas a little bit more from the austere side than I do from the hedonistic, if that makes sense. I’m not so much interested in the pleasure of excess – not that that’s not pleasurable, but I think pleasure sometimes is reduced to fun and joy and consumption. And the thing about fun and joy is that they tend to be individual. Don’t get me wrong, joy is very collective, but with the erotic it can be egocentric, about me and my experience. And when you collectivize play or, dare I say, ritualize it, it becomes a collective goal – it’s a fantasy everyone is sharing. So, I think the way I’m thinking about pleasure right now is sort of a byproduct of that, but it is not the goal. You know, the goal is to have these deep, meaningful connections that are earth-shattering and that can transform our interiority. And if we experience pleasure in that process, dope.

SS: Madsen, when you were talking about pleasure being primarily associated with fun and joy, it made me think about adrienne maree brown’s book Pleasure Activism, where she describes pleasure as a deeply satisfying experience. That doesn’t necessarily mean these experiences are always fun or joyful; there can be expressions of rage and grief that can be deeply satisfying and pleasurable as well. There’s also satisfaction that connection can bring. This has been a way that I’ve tried to help people understand what I mean when I’m talking about pleasure, because so often when I interview people they go straight to sex, and I’m like, Well, yes, but there are also all these other kinds of pleasures that we can experience. And for me, in these communal spaces of a party or performance, there’s a lot of pleasure in the collective connections.

AMM: Totally. It is in those party spaces when that collective energy gets brought out. When people are playing behind closed doors or individually, it’s harder to understand what that energy looks like – when that collective mobilization starts to happen and the people are pinging off each other and energy is building. And so like jouissance … the only way I’ve ever heard it translated to English directly is as the word “pleasure.” But the translation is expanded upon, it becomes more like “ecstatic.”

JC: Not just intimate but also extimate (what Jacques Lacan named extimité, or the intimate exterior) – an ecstatic, but also potentially terrifying, opening into and onto precisely something that would be more than you, and even estranging from the way you understand who you are. I’m thinking here of Leo Bersani’s “Is the Rectum a Grave?” and that famous line, “There’s a big secret about sex: most people don’t like it.” In other words, why do people fear and, thus, regulate sex? And there’s a version of an answer which is that jouissance – far from a synonym for orgasm – gets us to the way that sex can be not self-confirming but self-shattering. Sami and Madsen, you’ve both underscored “intention.” So that seems like a key piece of what might distinguish particular kinds of pleasure practices: that intention distinguishes the pursuit of desire (wherever it might lead) and radical jouissance from casual fun – even as what starts out as casual might not stay there.

Michelle Handelman: I love thinking about how jouissance gets us to a state that can be self-shattering, or an obliteration that allows us to rearrange. This is exactly what I’m looking at with my new project DELIRIUM. I’ve been making moving image work for decades now, and ever since the beginning, desire and pleasure have been my activators. The erotic impulse brought me to my camera – a hedonistic urge to be swallowed up by submerging myself in the excess, then capturing it through my lens. Much of my early work was motivated by my desire to have sex with someone. Almost like art-making was a subterfuge to get us both naked! But now, dealing with my body breaking down due to age and overuse, I’ve been thinking about the difference between pleasure and desire, thinking about how pleasure is the narcotic and desire the stimulant. Pleasure can be this beautiful opiated state that allows a languorous embodiment that permeates every cell within your body. In a way, pleasure erases pain. Which is exactly what a narcotic does. Be it physical, social, or political pain. Desire is more like a stimulant, an agitation, a proposal. An interstitial state which can lead you to pleasure or the opposite, a hole waiting to be filled.

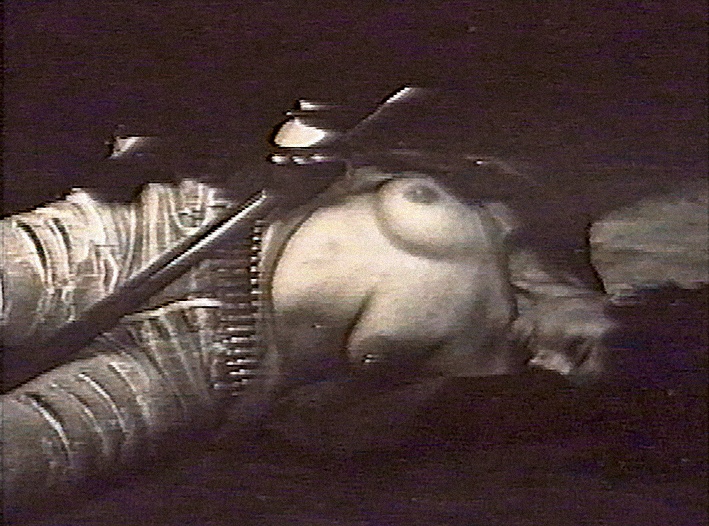

Michelle Handelman, “DELIRIUM,” 2023, production still

In my project Hustlers & Empires, there’s a character based on Marguerite Duras (played by Viva Ruiz) who’s on this surreal talk show, and one of the questions she’s asked is, “What’s more important, sex or desire?” She eventually says, “Desire … because you can have that all the time.” I loved that. So being the greedy pleasure pig that I am, I started to think about desire as something that you could have all the time. What does that look and sound like? And this led me to DELIRIUM, which at its core is about embodying, but also about getting rid of the body, and getting inside a constant state of desire and outside the cycle of capitalist production. Perhaps desire is in and of itself pleasure, as it lives through the imagination and has yet to be negated. Ultimately, I think about pleasure and desire not only as subjects for work, but as conditions for my work and conditions for living, really. And my relationship to making my work is completely sadomasochistic! Sometimes I’m the top. Sometimes my work is the top. But most of the time my work is the top and it’s fucking killing me! Making me submit to things that I didn’t think I was capable of. These relationships of power between the maker, the work, and the audience are a crucial part of the process for me.

AMM: I love “desire as a way of life.” And I think it can occupy that space of the “God Hole” – that people have this need for something fuller, beyond oneself. But I think the danger of it is that it’s a byproduct of capitalism: we want what we want when we want it, how we want it. And how do we separate that? That default collapsing of desire as the need to consume whatever we want. It gets tricky there. And then there was something you said earlier, Michelle, about pleasure as a narcotic that erases pain. And one of the things I’m super interested in is thinking through the ways that integration is possible. Pain can never be erased. There’s no erasure for pain. But as we engage these activities we seek integration with the pain. And this itself is the pleasure. I think that’s where I’m moving with new work – just figuring out where that integration happens or how it happens or what its conditions are.

MH: I agree, pain can never be erased, yet I see the transformation of pain through pleasure as a form of respite. Ultimately, the integration has to happen because we all carry those layers of pain within us, but if you’re not ready to deal with it, pleasure can be a good drug.

AMM: Yeah, I think the narcotic is the choice to not integrate. Whereas going into the pain is the choice to integrate.

JC: There’s that intention again. Something else that stuck out for me is how we can understand BDSM and kink as ways to “do things with being undone,” practices that don’t just trigger or bring out the damage but do something with that damage. What you were saying, Madsen, prompts us to think about the practice of BDSM and kink as ways to shift our relationship to damage, including our own. Sami, I know that so much of your own collaborative visual and performance work, your work with adrienne maree brown on pleasure activism, and your research into pleasure practices and play in multiply marginalized communities are a way of working within the struggle against histories of trauma and damage and to do something else with the ways that to continue to be part of an activist struggle can be to just wear yourself out. You also have a collaborative practice in which you’re working with various photographers to share out your pleasure activism, but also taking the stage at some major events – twerking with Lizzo, dancing on stage with Janelle Monáe.

SS: Madsen, you’re suggesting there’s a relationship between desire and capitalism, and I think it might be useful to distinguish between a desire for a thing versus desire to do a thing or to be a thing, the latter two being aspects of desire that may not be as tied to capitalism, even though I feel like everything is in the end. With pleasure activism work there’s the idea that pleasure is an aspect of our aliveness; it’s the point of life; it’s a thing that we all have the capacity to do. But oppressive systems like capitalism make it harder for some of us than others to access pleasure because our pleasure is criminalized and policed and legislated in certain ways. My artistic work is very much about just being in my fat Black disabled femme body in public in ways that have historically been viewed as wrong or shameful. I think it took me getting to a place of having a little job security through tenure to feel like it was finally okay to do so openly.

Sami Schalk, photographed by Sam Waldron (Reverence Intimate Portraits)

I talk about this a little bit in my contribution to Pleasure Activism. For years, I thought if anybody found out that I was kinky, I was going to lose my job, that there was just no way that I was going to have a job in academia. But I love the photography work that I’ve done, particularly with Sam Waldron, who runs Reverence Intimate Portraits. We work as artistic partners, and we’ve done these kinky photoshoots with rope and leather to really put this aspect of my Black queer disabled life into the world in a way that is intimate but also an empowered claiming or reclamation. A lot of the work that I’m doing with the kinky pleasure spaces in particular is talking about how kink spaces have been really difficult for disabled people and people of color and potentially quite harmful. That’s one of the reasons that these spaces by and for multiply marginalized people are important. It’s really hard for some of us to safely have a kink practice in general, but then even within the kink world, within dungeon spaces and play parties, we’re still fetishized or at risk for other forms of exclusion and harm. So that research-based knowledge along with my own experiences informs some of the artistic work that I do, and it’s why I put images of me in rope and such into the world, to kind of claim that space for folks who feel like it’s not for them or hasn’t been safe for them before.

AMM: This is tangential, but I’ve been going down some hard Bob Flanigan holes. I love his resistance to simplifying everything to the experience of identity. In some ways, everything is about the doing and not the being. That really resonated with me, when everything feels about the being and not the doing right now. I feel like there’s a lot of pressure to self-identify, to create boundaries around what our experiences are and what we’re bringing to the table. It feels like there’s more emphasis on reading the being and less of an emphasis on reading the work. I really admire the practice of people where the work is the work, it is the doing.

MH: I think it’s really important what you are bringing up, Madsen, because the doing is actually what’s political – a refusal of containment. The doing is meant to be witnessed outside of hierarchies.

AMM: It’s like saying, I’m not gay, I just have butt sex with boys. You know what I mean?

MH: Yes, exactly. I think the doing is an important position because it provides space for people to stand on the same ground with clarity, without judgment. I think the strength of Bob Flanagan’s work is that it comes from a place of deep curiosity, of survival, of play. I’ve always appreciated the way Bob freed SM representation from its secret history and made it completely accessible. If you ever went to one of Bob’s performances, you know this. He would be standing there with his balls nailed to a piece of wood and just be chatting with you about the weather, or how your day was going. He had this ability to take something so forbidden in our culture, forbidden to the point where we don’t even have language to talk about it because we’ve never been taught how, nor even been allowed to talk about it, and move it to a space of the everyday. His approach was kind of quotidian, much different than Fakir’s, whose practice was deeply tied to history and spiritual rituals. And there’s something quite remarkable, quite powerful, about people who are doing remarkable things in an unremarkable way.

AMM: I think that the struggle is in understanding that the doing is boundaried by various access points. We’re trying to draw attention to those access points, not let them be continually rendered invisible while still allowing for the freedom of the doing and the freedom of jouissance – of the unnamed and the unknowable. And having access to that which is not named. But to understand our behaviors and our relationships with each other, we do need to be able to codify and name these things. Whatever enculturation prevents us from accessing certain things – the nature of oppression prevents this doing.

JC: I’m really curious about this insistence on the doing and particularly the way it gets us to a key aspect of the politics of BDSM, kink and pleasure or lust as political by way of confronting us with how doing undoes certain kinds of identitarian conscription. Related to this radical potential for undoing identitarian demands is the way doing defies aspects of language. But I’m hearing this echo of kink as not being academic. And I’m not sure I agree. When you were describing, Michelle, a desire that permeates everything, I felt like the books on my shelves were vibrating in a particular way. And for me, desire – not lack, but that electric crackle – vibrates as it motivates both the scenes of pedagogy and research. I don’t know whether that’s an SM relationship or not. But I think it’s certainly a kinky relationship that I have with what is described under the umbrella of the “academic”: asking impertinent questions, figuring out ways to make knowledge-making do things that it’s not supposed to do. Let’s consider how putting the practice of BDSM and/or kink into the center of our consideration of desire and pleasure does something to our consideration of how power works: the ways that it forms and deforms us, but also the ways that we can channel and work with damage and trauma and develop agency. Let’s speak then to the ways that you might understand BDSM and/or kink and/or pleasure as political in practice.

SS: I think it’s just the association with deviance. You know, deviants are not supposed to be the people in front of the classroom, even though so many of us are. For me, in particular, I was concerned that people would assume, by knowing about kink in my life, that I’m inherently sexual in my class or more sexual as a person as a result of the way that I’m being perceived, in similar ways that I think queer people often were and are. Also, for me at least, as a Black, queer, disabled woman in the academy and in front of the classroom, there’s a way that I feel I need to be very much in a position of power, authority, and control in my professional life. And I have had concerns that people knowing that I’m a submissive bottom in my private life will take it the wrong way, with people conflating my personal and professional existences. Rather, I think most bottoms are very powerful people because they’re determining so much of what’s about to occur. So, I think those are the ways that stigma, power, and oppression shape the politics of being out about BDSM practices. But I also think practicing kink is politically powerful. Kink practices like negotiation and aftercare are valuable whether or not you’re a kinky person. Kink practices are empowering and help people to pay attention to power dynamics everywhere and to ask more questions about consent and desire.

Angelo Madsen Minax, “My Most Handsome Monster,” 2014, film still

I teach a disability and sexuality class where we read A Quick and Easy Guide to Sex and Disability, which mentions a little bit about toys and kink. But it also has this questionnaire that I have the students fill out and I say, “I don’t ever want to see this. This is for you to fill out on your own and then we’ll talk about what it was like to fill it out. But we don’t need to talk about anything that you actually wrote down.” So some of the questions in the book are about words that I like to use or hear (or not use and not hear) during intimacy, places that I want to be touched or not touched, things that I want to try, things that I might need help with or that are hard for me, and so on. Most of my students have never thought about any of these questions ever. And a lot of them tell me that they end up having conversations with friends or partners after doing this activity. In the context of the classroom, I don’t tell them that this is how kink works, but that the ability to negotiate is important. And negotiation as a norm, after care as a norm, as a standard expectation, is political. I think it’s empowering for the way that people not only go about their sex lives but their whole lives by having this expectation that people will ask for consent before they touch you in any capacity. Or that we’re going to have conversations about what works and doesn’t work for us without the assumption that what worked for this last person I was with probably works for you, too. That’s the kind of stuff that I now feel more comfortable being explicit about, because I think we can talk academically about Bob Flanigan, but to actually talk about negotiation practices in detail requires you to have experience with this negotiation practice in some way.

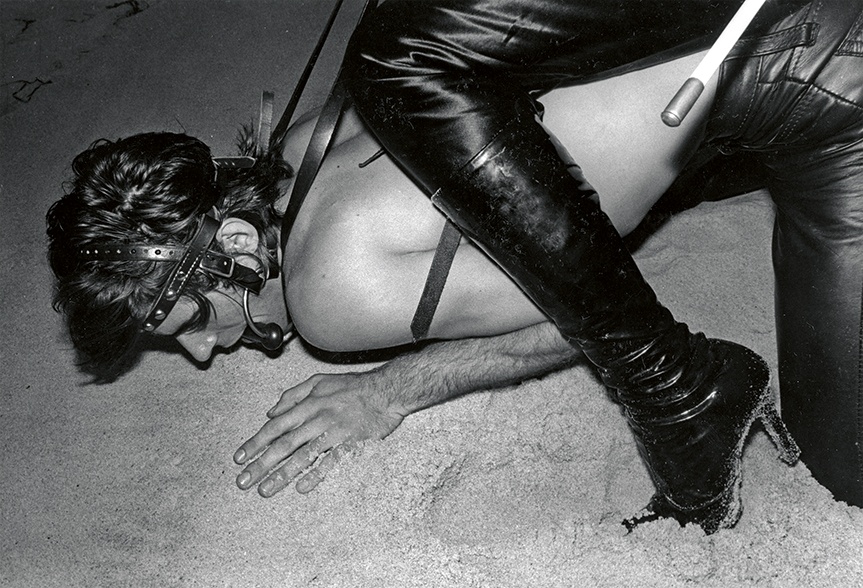

MH: Yes to negotiation! In 1992 when I started shooting BloodSisters, I came to it as someone who had been doing BDSM since the age of 13 but had never been part of a community. I grew up around my father’s massage parlor, so deviant sex was out in the open. I had been to sex clubs, but most of the play I engaged with was with myself, and occasional lovers, or strangers. As I started making BloodSisters, I found myself in a new milieu that was all about community, care, and activism, and one of the things that came up over and over again was the importance of negotiation. BDSM may be one of the few experiences where you have a say over what you will, and will not, have done to your body. Ms. SF Leather 1993, Queen Cougar, says in the film, “I now have the ability to choose what I will and will not have done to me. I didn’t have that before. In the past, shit just happened. Well now, shit rarely happens to me anymore.” Unless you’re part of the white male supremacy, you’re not going to have this choice. Your body is constantly policed, controlled, legislated. People who have very little agency in the rest of their lives become self-actualized through BDSM. For many, it’s the first time they understand their value as thinking, feeling human beings, and what it means to not only have agency but take agency, to speak it aloud. And once you experience that you have new tools at hand to build your world in a way that works for you, not your oppressor. This was very revelatory to me. I was versed in deviance, but not in the power of community and its potential for radical power shifting. It was at that point that I realized the fullness of BDSM’s revolutionary potential. That was why I made BloodSisters – to amplify these political voices and give the rest of the world the opportunity to learn what I had learned.

AMM: I’ve been practicing BDSM since I was 19 years old. And I was in a very intensive three-year-long, 24/7 D/s relationship with someone significantly older than me. There were a lot of dynamics troubling about it, but also a lot of things that just completely opened my life up in these really expansive ways that young people don’t often get. It’s rare to have an older person coming in, holding your hand, and telling you this is how you do this. And back then, I was still in a position of wanting to please and prioritizing other people’s pleasure over my own. And I think a lot of that is just basic female socialization stuff, that my counterpart should be taken care of. Then I had this huge breakthrough a couple of years ago at a fag party, because for them, often, everything is just about what they want. And it made me realize I only have to do exactly what I want. Some gay men fetishize certain sex acts with trans men that I don’t generally enjoy but will sometimes let slide because that’s what this person really wants. And I had this whole breakthrough crystallize, while fucking, that I actually can do only the things I want to do. Not even the things I like to do, but the things I want to do, right now with this person. It’s so entangled in the way culture shapes us, but the fact is that I’ve been doing this for 20 years and consider myself quite skilled at negotiation and this didn’t happen until entering this gay male cruising culture, specifically bearing witness to that, to how those encounters work, because there really is no negotiation. Well, that’s not true. There is negotiation, but it’s all done differently. It’s done without the language we would use in BDSM, especially in queer AFAB BDSM circles, where we’re talking about what we like, what we don’t like, and intentions and all that. The fags are just sort of, oh, you don’t like it when I touch you here, so I’ll just move my hand somewhere else. You know, it’s all trial and error in this very different way that allowed my brain to make the connection that, Oh, I say no now. And you just respect that.

SS: I think this is an example of those moments where being and doing are not separated. Your being, in the way that you were treated in the world, is shaping what you even know is possible to do. This is a reason why we say BDSM is a practice; it is a thing that you just get better at, that you have to learn. Because for many of us it requires such a deep unlearning of other things that we’ve been taught up until that point.

AMM: The thing that is most fucked about it, though, is that I had to enter this other space and bear witness, you know, looking like one of them. Like I had to hard pass to be able to kind of understand that in a different way. It’s a head fuck.

JC: On that experience of the head fuck. I seem to keep going to that place. I am also wondering in that scene that you set up for us, Madsen, of a coming together as a political assembly that’s anonymous, that’s not bounded by identity but would, rather, in the space of the shedding of identitarian demands to show up in a particular way, bring us together into a kind of commune or a collective of some really radical kind. And that made me want to ask about some of the ways in which we could understand BDSM and/or kink and/or lust and/or pleasure as political because it shifts the where, when, and how of the doing of politics. Sami was suggesting that the students come away from the classroom with a new sense of agency, but maybe every encounter becomes a space of a different kind of agency. And I know, Michelle, the work that you describe is so much about creating particular, or I would describe it as a particular stage set, or spaces for really opening up deviance, and even the capacity for deviance as a political space, or different states, like delirium, that one might think of as apolitical, you pose as a really important vehicle. BDSM and kink might be understood as political because of the shift of the where and when.

Michelle Handelman, “BloodSisters: Leather, Dykes and Sadomasochism,” 1995, film still

SS: This is just a tiny comment, but it makes me think about Mistress Velvet, a Black Domme who made all of her white male subs read Black feminist theory. When I read about that I was like, yes, chef’s kiss, I love that so much.

MH: There are so many aspects to BDSM that are political, legislated, actually. Let’s just start with the fact that BDSM play is illegal in many places around the world. To participate in BDSM is not only a social and religious transgression, it’s a political transgression, and the stakes can be really high. As Patrick Califia says in BloodSisters, “Our lives have been made political by our sexual orientation. So there’s no aspect of our sexuality that we don’t look at.” Patrick goes on to talk about his books being banned, and of course BloodSisters was censored, too. You also have BDSM discrimination within the queer community. Sami, you were talking about how you were afraid of coming out in the world of academia because you were afraid of losing your job. This is exactly why Gayle Rubin refused to appear in BloodSisters. I spent hours at her house shooting her archive, but she drew the line at appearing on-screen herself. She told me that when she started publishing her work on the men’s leather community she lost her job, lost friends, all of it. And clearly that negation of her life from people she had once trusted still affected her deeply. There is very real discrimination and oppression coming from the outside that most people are unaware of unless they’re part of the kink community. As Donna Shrout says in the film, “Everyone’s been tied to a bedpost at some point, but nobody wants to say SM, that this is something I do in my life.” Silence is another form of oppression, and of course we all know that many of these silencers, from academics to politicians to clergy, are closeted hypocrites! So yeah, just by saying you’re into BDSM, you’re standing up against history, religion, governments. From my experience, nothing scares people more than SM – it’s a potent cocktail of sex and pain that refuses the trappings of respectability.

AMM: Thinking about time and place, this is all directly connected to the Spanner case – where all these guys in the UK got arrested just for having kinky sex. It’s directly connected to satanic panic, directly connected to AIDS and fear of blood. And I partially feel that the way we’re seeing BDSM and kink culture come back into collective awareness is generational. The generation that grew up during AIDS was conditioned that queer sex would kill us. And the folks that were a little bit older than us were already doing all this inventiveness, like wearing gloves, figuring out alternative hot sex practices that weren’t penetration. There is a Reagan-era container around this that’s hard to separate from.

MH: Yes. But it’s both older and younger than the Reagan era. The Spanish Inquisition invoked false BDSM practice to persecute and torture women, and even now, after the Spanner case, the AIDS crisis, you have young queer folk, people in their 20s, who still don’t want a leather contingent at pride!

AMM: Totally. Even in my teaching. I have a former student from seven years ago who works with me now as a research assistant, and he was like, “What’s that film you showed us, that first video in class?” And I said, “I don’t know what you’re talking about.” He described it, and it was hard core. I was like, “I showed that to you?” He was like, “On the first day.” Wow, cool. I would never show that now. And part of it is that people don’t want to fucking see it. There is a weird prudishness around sexuality right now that has filtered into this. And this is getting me out in left field too - but it’s even related to the overuse of trigger warnings, especially around BDSM practices, which further stigmatize them. I’ve had issues like that come up in class where it gets reductive fast, and this is more complicated than just violence. And there’s this polarization thing happening. Obviously, we’re a very, very polarized world right now.

MH: It’s interesting to think about these contrasts – you, Sami, teaching students about BDSM practice and its tactics of care, next to Madsen saying how he can’t show certain work to students that was acceptable, even desired, ten years ago because his student body has shifted to fear instead of curiosity. In my teaching experience I see students asking for trigger warnings because they think it’s a form of care, but they actually miss the point that trigger warnings stifle their ability to actually learn care tactics. It denies someone the opportunity to think on their feet and wrestle with ideas, or images, that make them uncomfortable, so they can understand the disruption as something for which they need to rely on themselves to find a way through. This is one of the most important life skills to develop. Sex can be confusing and intense, BDSM is dangerous. That’s all true. But that’s only part of the story. BDSM offers one of the safest sexual experiences one can have precisely because of the care, the conversation, the community, and the unique safety net of negotiation and safe words. There’s just so much ignorance and fear out there. Maybe it’s a result of young people growing up on disaster porn and the 24-hour doomscrolling cycle that has them begging for a safe zone. “Care” and “safe space” seem to be the current buzzwords of academia and the art world, yet within this paradigm the uncomfortable thing is usually positioned as something one can opt out of, and that’s just not how life works.

SS: I mean, trigger warning requests are coming from my progressive students who are trying to make the world a better, safer place. I think some of the misperceptions of BDSM comes from the particular visibility of it in recent years, like Fifty Shades of Gray and kinky social media kinds of stuff. But to me these representations often seem not aware of actual BDSM practices or to be not a good representation of those practices because the negotiation, the aftercare, gets left out for the most salacious parts of it, which for me is just such a sliver of BDSM. I mean, yes, those parts are what we’re preparing for with negotiation, but I don’t know, I’m a type A person, the planning is part of the appeal for me. I’m like, Ooh, look at us making a plan together. I love a plan! And planning or negotiation requires you to say what you want. I think a lot of people don’t know what they want, and they assume that anything they experience that they didn’t like is inherently violent or abuse rather than a learning experience to figure out what you do and don’t want. Sometimes we have bad sex – not abusive sex or coerced sex, just plain old not great sex – and then we learn what we like more from those experiences. That’s part of figuring it out sometimes. But I think it’s a real challenge, because for many people, I didn’t like something becomes this other more harmful thing due to lack of negotiation skills. People either don’t know how to say what they want or what they don’t want or don’t know even what they want or don’t want in order to say no clearly.

Sami Schalk, photographed by Sam Waldron (Reverence Intimate Portraits)

AMM: Part of the “I didn’t like that” thing is that it’s not always that the person didn’t like it. It’s that it made them feel something or encounter something that was unexpected. Sometimes it’s as easy as I don’t like it, but oftentimes it’s an issue of where you go internally in response to that impetus. Like, this is a place I didn’t want to go. And it becomes such an interesting kind of relational dynamic in moments like that, because your brain is the one that went there. You know what I mean? How are you going to hold your own brain accountable? I think these things that we’re doing on a micro level, even language, like the nature of certain language or the nature of a tone or a smell or whatever. Those are more interesting things to think through than the ones that are more clearly about how an actual physical activity was uncomfortable. Those are where your interiority is actually doing most of that work. What does that leave you to sit with?

SS: And I think that’s part of it, right? Forcing us to sit with what happened internally and why and sometimes not being able to identify an exterior factor necessarily. That’s one of the things I really like about good BDSM dynamics that I’ve had; there have been moments where I’m like, What just happened in my brain? What flipped a switch? I’m gonna have to go think about that and come back to you because something went in the wrong direction, and I cannot tell you why in this moment. I just know I’m not in the right headspace anymore. Sometimes it takes me a minute to identify the thing and sometimes it takes much longer or requires conversation with my top or a friend to process. And for me, the kind of interior work that BDSM practices require of me creates such a deep sense of knowing oneself. And, again, here I think this translates into the larger world and that part of the political danger of it for folks who don’t want kink to exist: there is a self-assuredness and a knowing in encouraging us to really understand our deepest desires and to not assume that those desires translate for other folks. There are a lot of things that people are into in BDSM that I’m definitely not into, but I can see it brings them so much joy. I think there’s so much value in being able to think, Wow, that thing that I would never want is, to this person, just the very best thing. It’s a good reminder that pleasure is so different for all of our different lil’ brains.

MH: Yeah, it really is. It’s so important because it’s only when you’re open and thinking through all these things that you discover your limits. And when you discover your limits you have to question them. Where did these limits come from? Is this my limit, or my mother’s limit that she imposed on me? How do I unlearn them? There’s this saying I heard while making BloodSisters: “If you think you don’t have any limits, then you just haven’t found them.” We don’t have a lot of places where we come up against these things in such a deep way outside of BDSM. When you find that limit that you didn’t know existed, you’re presented with a choice: Do you push through? Do you stay where you are and not trespass? When does the trespass become a transgression? That negotiation process is different from the other BDSM negotiations we’re talking about. This is a negotiation with oneself. And then of course it becomes a negotiation with your entire history, your family, your ancestors, everything that has gone into the making of you. It’s a lot to handle, and some people just can’t handle it. It’s scary to find out who you are.

JC: I was just thinking as well about this being an especially roiling moment in which to understand kink or BDSM as a political pedagogy in the kind of radical sexual freedom that we’re not supposed to have: a freedom to do without being any particular socially demarcated categorizable, surveilable, containable, or governable subject. As I wrote about your work, Madsen, in an essay I called “Kink as Method,” the chains, clamps, and other contractions that bind may also reassemble not to repeat but perhaps even to break cycles of phobic violence by expanding how kink may make kin that doesn’t depend on binary kinds by taking us on the journey of radical coming and coming into otherwise being in relation. [1] And I was wondering if it’s worth speaking to this moment in which anti-trans legislation is happening at the same time as prohibitions on anti-racist teaching (and an outlawing of teaching critical race theory) and efforts to ban teaching sex and gender – beyond the cisheteroreproductive – to children. And I think often, Michelle, about your article “The Magical Buttplug and the Phantom Child” [2] in which you talk about the censorship of your four-channel video installation Dorian, A Cinematic Perfume at Arthouse in Austin, Texas in 2011, which was done in the name of the protection of the phantom child. That presumptively not Black, not nonbinary, not queer or trans child, that child to be protected, it was made very clear, is never us – those of us who are the danger we have been warned to avert. For those of us who are made to feel the exclusionary force of the implied bar flashing behind the beware of “this may hurt the sensibilities of the public” (that implicit barrier that tells us we are somehow not an integral part of what is imagined as the public), the X-rating system introduced in 1968 also lights the way. For many of us, rather than a block, the crossed geometries of the light lines that compose the triple-X illuminate the get-out of our get-away, offering wayfinding devices into the back rooms for more than surviving the unbearable. Frankly, you know, content warnings, trigger warnings – those were my wayfinding devices, ways to find my people. Follow that stanchion or rope to the marked off area, this is where I might figure out how to survive. So, in this really rough climate, let’s turn to the emancipatory potential of BDSM and kink, and to pleasure that’s not identical with the commodified of capitalism.

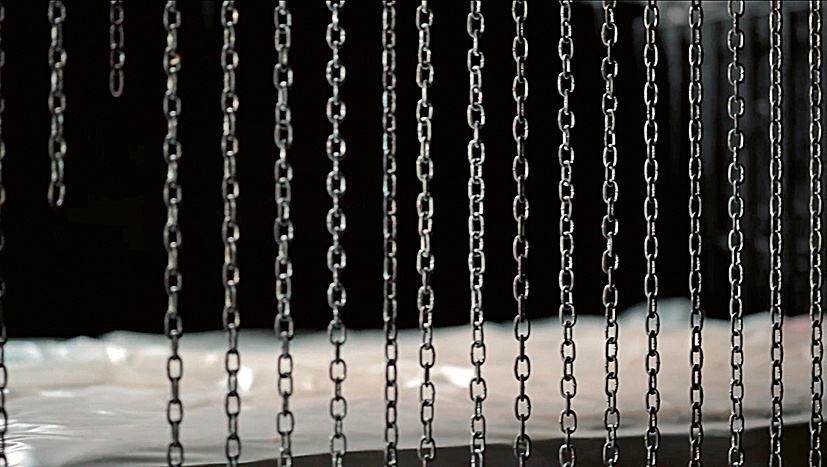

Angelo Madsen Minax, “Rehearsals Toward and Erotic Approach,” 2022, video still

SS: Earlier we were talking about safe spaces, and it made me think of one of the organizers of a queer dance party who I interviewed who said they don’t use the term “safe space” anymore because they realize they just can’t guarantee it. So they started calling it “brave space.” I appreciated that because a lot of the organizers I’ve interviewed talked about how when we’re creating these spaces for multiply marginalized people, we are creating spaces for traumatized people who bring their trauma into this space and who are going to react to things that they don’t even realize they’re reacting to. There’s a really high standard for safety and care when we’re doing these multiply marginalized community events. In talking to event attendees, many explained how the event they were at was one of the few spaces that they feel to be as free as possible because there is no white gaze, for example, in some of these spaces. So, I’ve been thinking about these spaces as giving us glimpses into liberatory futures that allow us to say, Look, you can’t tell me that I can’t have a really empowering sexual experience that involves pain, because I’ve experienced it. You can’t tell me that we can’t make an accessible kink space, because I’ve experienced that. At least once. And so for me, these spaces are creating moments that seed a belief in the possibilities of freedom. Maybe in this current world we can’t do this all the time, because it took so much work to make it happen in this one moment, but it opens up our political and social imaginations to say, I have seen, I have experienced, and therefore I believe it can be created again or created more often. For a lot of the organizers, the desire to create these spaces came out of negative experiences in other spaces and wanting to create something different. So these kink spaces intentionally created around multiple and marginalized communities are giving us these really magical, powerful, unique sexual experiences that help us understand that what the world says is possible or what the limits are, are just not the limits.

JC: I love the formulation of “as free as possible,” but also that opening of the aperture onto liberatory futures. Once you’ve got the actual experiential taste of what can happen, you have that in you; you carry that along as a refutation, a no or not necessarily so to counter the message that the world somehow has to always be that oppressive other version.

SS: And I think even beyond these specific multiply marginalized spaces, Madsen, what you were talking about before, with that experience of realizing you’re allowed to behave this different way, move in this different way, and negotiate in this different way, where if you say no it is heard, that also opens the possibility of thinking, Well, I now will not tolerate another experience in which people don’t just take my no, because I know that that is a way things can happen. These spaces and experiences can just shift our standards and our expectations of ourselves and of the way that other people behave toward us.

AMM: And there really is something to the standard being so high for those in the multiple margins. It’s like the fewer the margins, the more room you have to do these things and figure them out as you go – there’s less potential for harm than in other spaces where potentially the people playing are still really working a lot out. The more shit we’re dealing with, the higher the standard is set, which has a direct effect on longevity. It’s like the exact reason the Inferno parties in New York can go on for years. Because there are fewer margins, which equates to fewer demands being put on people, and the Inferno parties are great. They really clearly lay out their politics right off the bat. Then other spaces that are being created have a three-year lifespan because it’s just fucking exhausting work.

JC: Michelle, when I did the intro for the new Kino Lorber release of BloodSisters, I found myself responding to rewatching by saying that the film participates in an erotics of truth-telling that puts us into the scene of “using our bodies as everyday incubators for active pursuit of radical pleasures, using radical pleasures as the spur for living experiments in anti-capitalist, anti-respectability, and anti-gentrification politics in the everyday – showing us how BDSM is also the medium for ritual, for community care, for mutual aid practices that bind the sexual and the economic.” But I also feel there’s something really exciting in your new project, DELIRIUM, that might speak to this question of the emancipatory potential of BDSM and kink or just desire.

MH: I just keep coming back to this access to forbidden knowledge, and how once you’ve decided you’re going to find out what’s behind the closed door, you’ve emancipated yourself from something. It’s not like you’re totally free, but there’s this crossing of thresholds. And every time you cross a threshold you shed something, and the shedding process is what’s emancipatory. But the unlearning and the shedding can only happen when you’re present and aware. People can’t make you walk through the door. They may push you through the doorway, and you might find yourself standing on the other side of it, but that still doesn’t mean you went through it, that you actually crossed a threshold. It may be a collective moment or something completely solitary, but still you have to make the choice to open up your eyes and see who and where you are.

Jimmy DeSana, “Untitled” (The Dungeon series), 1978–79

AMM: When you go deep with yourself, you’re cultivating an internal landscape, figuring out your interiority. I think there’s something in that that allows you to have these revelations in your waking life. You don’t have to be in a state of fucking to necessarily arrive at the I get to only do what I want realization. There’s a way that knowledge becomes embodied. And lots of us, we have knowledge. We know that oppression is real and dictates how we move through the world, but then there is a tweak that happens, and you understand it in an embodied way that your consciousness actually shifts, and your physicality re-forms around that consciousness to interpret that shift. And as a result of exploring those shadowy places in my life, I have more access to that potential for shift. I can now have those shifts all the time. I feel like I’m constantly having moments of understanding something completely anew about my own racism or my own fatphobia or my own pleasure-giving. Like the capacity to cultivate that skill set, because throughout your life, it is still possible to continue having revelations about the world you occupy. And in some ways, those revelations when shared communally are literally awesome.

MH: Exactly. They’re paradigm-shifting. Once you walk through that door, once you’ve crossed the line, you can’t go back.

JC: I’m reminded of the line in the writings of Jimmy DeSana that says: “Once you cross the line, the line becomes you.” We’ve described a provocative tension between BDSM, kink, the pursuit of desire wherever it may lead as the possibility of leaving yourself or even certain kinds of identity categories and entering a space of doing, and somehow, at the same time, ways of consolidating aspects of a self that you didn’t know you had or could have. And that feels like a really important dynamic to keep in play.

SS: I just want to say something about the fact that within kink communities we talk about things as play because I think as adults we don’t play, and sex is a kind of adult play. I think that language is intentional and useful.

JC: Seems like a key aspect even of the last question of emancipation – how a practice of emancipation might be in play, if play entails shedding some of that adult constriction and opening up the zone of experimentation as a way to engage with not knowing, as a way to practice curiosity.

AMM: It’s very rare that we as adults actually go into a situation where we know nothing about what’s happening or what’s going to happen. We don’t put ourselves in those situations. So we lose that flexibility and that way of interacting with the unknown or the unlearned. There’s a certain type of growth that gets rigid and hardened, and the play keeps its malleable.

MH: I don’t think that it only has to do with age, though. I think it has to do with technology. There are no more surprises because now everything can be researched in advance. Before going to a dinner, a party, a film, everyone looks up everything: What should I wear? Who’s going to be there? What do they do for a living? What’s the safest route? GPS has taken away our ability to “get lost” and discover delicious, dangerous unknowns. And the algorithms just reinforce what we already know. There’s no room for play, no challenge of working your way through something because we know where we’re going at all times. And if we get lost, we just pull out our phones! I think aging is part of it, but I think technology might be a bigger part of that equation. Particularly because younger people know that their every move, their every word, is being surveilled. There’s this insane fear of saying or doing the wrong thing, of being canceled. It’s a new form of identity panic. No one can just be themselves. I’d like to come back to what Madsen was saying about desire and its relationship to capitalism. My question to everyone is: Where does desire live? Is it possible to experience desire outside of capitalism? Is it possible for us to do anything outside of capitalism?

AMM: I mean, it goes back to what Sami said about the potential for imagination. We can’t imagine it.

JC: Yes and no. One of the things that I was really interested in while rewatching BloodSisters was the emphasis on collectivity, the ways that we can rework and repurpose our bodies. That does feel like it’s shifting at least a version of capitalism that would insist on extraction, insist on productivity, insist on reproductivity, insist on a disciplined worker body. If we understand BDSM and kink as not the gear but the collective, then it’s not entirely just about an experience you can buy. I’m not willing to let go of the possibility that BDSM and kink and collective practices of pleasure could be a rehearsal for or micro-enactments that may rend an aperture in racial and carceral capitalism.

MH: Yeah. I mean, pleasure in and of itself can be a powerful denial of capital structure because it takes you outside the cycle of production.

AMM: In the sense that it resists labor and a tangible type of existence. It’s not an object or material. I think about it like, What’s shaping or determining the images that I’m drawing into my mind as part of my erotic landscape, my internal erotic landscape? How are those images pre-packaged for me by what I’ve been fed? And I mean, those movements to redefine that have been going on for ages. You know, post-porn. But still this persists.

JC: Yes, still it persists. Feels like a not bad way to end. Though I took the “this” that still persists a little differently: I was imagining our lust eating away at the insides of capitalism.

Michelle Handelman is a New York–based visual artist, filmmaker, and writer whose work resides in the dark and uncomfortable spaces of excess and nothingness. Coming up through the years of the AIDS crisis and Culture Wars, she has built a vast body of work confronting the things we collectively fear and deny: death, sex, chaos. Her exhibitions include solo shows at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, MSU Broad Art Museum, Performa Biennial, and at signs and symbols and Participant Inc, both in New York. She is a Guggenheim Fellow, recipient of a Creative Capital award, and is known for her work with drag legend Flawless Sabrina and collaborations with industrial music pioneer Monte Cazazza. Her award-winning film BloodSisters: Leather, Dykes and Sadomasochism (1995) is recognized as a landmark in queer history.

Angelo Madsen Minax is a multidisciplinary artist, filmmaker, and educator. His projects consider how human relationships are woven through personal and collective histories, cultures, and kinships, with specific attention given to subcultural experience, phenomenology, and the politics of desire. Madsen’s works have been shown at, for instance, the Berlinale, Sundance Film Festival, Toronto International Film Festival, New York Film Festival, Tribeca Film Festival, and dozens of LGBT and experimental film festivals around the world. He has participated in residencies at the Headlands Center for the Arts, Skowhegan School of Painting & Sculpture, Yaddo, MacDowell, Pioneer Works, Bemis Center for Contemporary Art, the Core Program at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and others.

Sami Schalk is an associate professor of gender and women’s studies at the University of Wisconsin – Madison. Her interdisciplinary research focuses on disability, race, and gender in contemporary US literature and culture. Schalk is the author of Bodyminds Reimagined: (Dis)ability, Race, and Gender in Black Women’s Speculative Fiction (Duke University Press, 2018) and Black Disability Politics (Duke University Press, 2022). Her artistic work as a pleasure activist has been exhibited at the Ford Foundation Gallery and will be featured in the forthcoming collection Disability Intimacy: Essays on Love, Care, and Desire , edited by Alice Wong.

Jill H. Casid is an artist-theorist and historian and holds the position of professor of visual studies with a cross-appointment in the departments of art history and gender and women’s studies at the University of Wisconsin – Madison. Casid pursues a research practice across writing, photography, and film that is dedicated to queer, crip, trans*feminist, and decolonial interventions. Casid exhibits their artwork nationally and internationally, including in recent exhibitions at the Ford Foundation Gallery and signs and symbols in New York, as well as steirischer herbst 23, and “documenta fifteen.” Casid is the author of Sowing Empire: Landscape and Colonization (University of Minnesota Press, 2005) and Scenes of Projection (University of Minnesota Press, 2015). Their work on forging solidarities and kinship across our throwaway world includes two recent films, Untitled (Melancholy as Medium) and Untitled (Throw Out). Their current projects concern the question of doing things with being undone in the Necrocene.

Image credits: 1. Courtesy of Michelle Handelman; 2. Courtesy of Angelo Madsen Minax; 3. Courtesy of Michelle Handelman; 4. © Sam Waldron with Reverence Intimate Portraits; 5. Courtesy of Angelo Madsen Minax; 6. Courtesy of Michelle Handelman / BloodSisters Archive; 7. © Sam Waldron with Reverence Intimate Portraits; 8. Courtesy of Angelo Madsen Minax; 9. © Jimmy DeSana Trust, courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W