DOOM LOOP Peter L’Official on Paul Pfeiffer at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), Los Angeles

Paul Pfeiffer, “Vitruvian Figure,” 2008

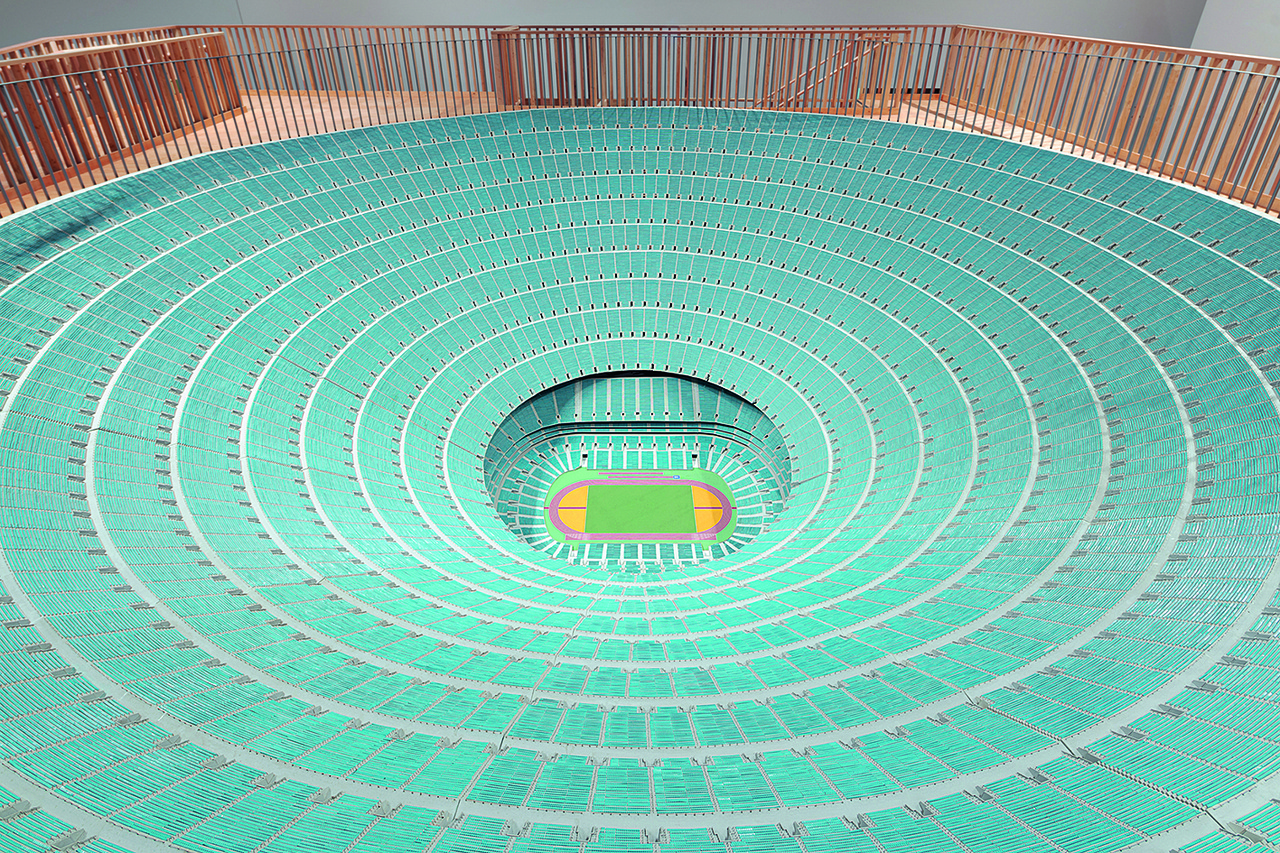

In 2008, for the Biennale of Sydney, Paul Pfeiffer commissioned Bligh Voller Nield, the architects of the 80,000-seat main stadium for the 2000 Sydney Olympics, to design an extension that could seat an audience of one million. The artist then contracted fabricators in Manila – Pfeiffer was born in Hawaii and spent his teenage years in the Philippines – to manufacture the million-seat architectural model, with each chair, concourse, and stair handcrafted, and the seating painted a breezy aquamarine. Titled Vitruvian Figure (2008), Pfeiffer’s monumental sculpture not only references Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, where the human body – circumscribed by a circle and a square – begets a system of proportion, but it also actively engages the spectator’s body within its own three-dimensional circumscription. To arrive at a point from which the enormity of Pfeiffer’s maximalist miniature could be comprehended, the viewer climbed a ramped scaffolding arrayed in a square around the circular stadium structure in order to achieve an elevated view of the field of play below. The placidity of the light-blue paint of the seating hardly mitigates the vertigo induced by the plunging perspective and the relentless regularity enforced by the stadium’s sight lines. Both journey and destination echo the processionals and pilgrimages that are ritual for religious devotees and those for whom fandom defines their congregation and certain sporting arenas their cathedral.

At the Geffen Contemporary at MOCA in Los Angeles, where Pfeiffer’s first US retrospective is housed, even the impressively scaled Vitruvian Figure seems dwarfed by the vast hangar-like space of the museum. Pfeiffer’s work plays well both within and against its temporary home: a city whose most famous industry is mass entertainment is a natural host for an artist interested in the spectacle of sport and the theater of celebrity – each often a quasi-religion in its own right – and how publics and identities are formed in and around these image-based reflections of culture and society. Vitruvian Figure adroitly captures the play between such notions, as well as their psychological and historical weight as felt by spectators and mediated by technology, and it invests our experience of the work with a sense of disruption and unease. Encountering a work like Vitruvian Figure throws our capacity to imagine time and the navigation of space out of human scale; we must negotiate both the scaffolded structure and the final, vertiginous view from above in an attempt to grasp its enormity, and even then we fail, because Pfeiffer’s stadium sculpture has grander ambitions. The structure gives literal form to the scenes at a World Cup final or at the Olympics; that is, we are confronted not merely with a space for the 80,000–100,000 spectators who would be seated at such an event but also with a built environment that could potentially contain some of the millions watching at home, not to mention those who will watch that event henceforth, on repeat, on multiple platforms, forever. Pfeiffer both imagines and realizes all of those publics in one grand gesture.

“Paul Pfeiffer: Prologue to the Story of the Birth of Freedom,” MOCA, Los Angeles, 2023–24

It is that visual echo, however – the loop – that holds special allure for Pfeiffer, undoubtedly because we, who have become constant spectators of our own lives and the lives of others, are fascinated with the loop as well. “It’s like a visual addiction,” as Pfeiffer described his attraction to video loops in a 2003 conversation with the artist John Baldessari, “something pleasurable that’s hard to resist. The eye gravitates toward incessant repetition, as if it wants to lose itself in it. For me, the temporality of the loop implies a kind of escape, as well as a kind of imprisonment. It’s seductive, so you follow. And then you find you’re locked in.” [1] These tendencies – which might also describe a contemporary society in thrall to the algorithm and the endless scroll as much as to the loop – are reflected in a work like Pfeiffer’s 2000 video, John 3:16, coincidentally the first work one sees upon walking into his exhibition. This piece is a revelation – pun intended – for it not only draws referential power from a Christian Bible verse often seen on placards at sports arenas in the 1970s and 1980s, but more importantly for Pfeiffer’s work, it also reveals the tactility with which Pfeiffer wields his editing tools as a sculptor would handle their chisel. Pfeiffer’s silent video – which depicts a heliocentric universe where a basketball is edited from the footage of multiple games to be centered in frame while players’ hands revolve around it – plays on a miniature LCD screen that emerges awkwardly from the gallery wall on a metal armature, a favorite installation tactic of his that invites the viewer into a more intimate relationship with the image. Pfeiffer’s video work is characterized by perfectly imperfect removals and erasures that gradually reveal invisible structures, or subtler bodies heretofore obscured, while at the same time lending the altered image a mystical, suggestive quality. Pfeiffer’s retrospective enables us to see the sculptural elements of his work, which demand that the viewer approach his miniature screens for further discovery, and also the manner in which Pfeiffer constructs the loop as a kind of sculpture-in-process: as arrested physical movement both frozen in time and removed from time’s normal course, an interval suggesting the infinite but degrading at its own rate, as would any physical object.

Pfeiffer’s work seems altogether prescient: the loop has become a language, a mode in which we speak to each other through the medium of the internet, through social media. We dream, at times, in GIFs; we laugh with them, at them, and through them; and we explain our moods with them, crying, laughing, dismissing, and questioning by way of such brief loops of film, television, and other moving images, often well distanced from their original context. We communicate with such images, and so much so that we are constantly scanning what we watch in the moment for perfect fragments to sample so that we might create new forms and phrases via meme. We think in the loop. And we live for the highlight, which exists for the fan on countless platforms and can be summoned via handheld computer with limitless replay. We can stay in that moment forever, should we choose to do so. It remains a question, however, as Pfeiffer noted in his conversation with Baldessari, whether we are imprisoned in that moment, too.

“Paul Pfeiffer: Prologue to the Story of the Birth of Freedom,” MOCA, Los Angeles, 2023–24

Prologue to the Story of the Birth of Freedom (2000), a two-channel piece that inspired the title of Pfeiffer’s retrospective, displays in a very particular sense what might be called the arresting nature of art. On one monitor, the film producer and director Cecil B. DeMille emerges from a curtain onstage to introduce his most famous film, The Ten Commandments (1956), only to quickly disappear; on the other, DeMille approaches a microphone stand but never quite begins speaking, the loop in both channels arresting his motion, frustrating it (and us), delaying completion of the act, highlighting the theatricality of an announcement that is never announced. But the title – of the artwork and of Pfeiffer’s exhibition – invites a literary analysis as well. The notion of delay is central to this phrasing: freedom is promised, yet we are only given its prologue, which precedes one version of freedom’s birth – not its flourishing, or its bounties shared. Freedom is quite clearly, in the timeline of Pfeiffer’s title, not yet here.

Pfeiffer’s parents were both classically trained church musicians, and his father was among the first US ethnomusicologists to study Philippine Indigenous music. Both his father and mother served separate terms as directors of the School of Music and Fine Arts at Silliman University, a Presbyterian school in Dumaguete, the Philippines. It is of no surprise that Pfeiffer, a child of academics and of two lands directly affected by the settler colonial interests of the United States – Hawaii and the Philippines – is interested in the notion of freedom, its promise or deferment.

One way that we might understand freedom, scholar Stephanie Smallwood explains, is as “a keyword with a genealogy and range of meanings that extend far beyond the history and geographical boundaries of the United States, even as it names values that are at the core of U.S. national history and identity.” [2] What Smallwood makes clear in her “keyword essay” from Keywords for American Cultural Studies is that “the duality of freedom and various unfreedoms is best understood not as a paradox awaiting resolution by the teleological unfolding of the United States’ ever-more-perfect and self-correcting expression of its destiny.” “Rather,” she notes, “it should be seen as evidence that the possessive individualist freedom enshrined in U.S. modernity depends on and requires the unfreedom of some category of fellow humans.” [3] That is, the “arc of the moral universe is long,” as Martin Luther King Jr. once optimistically noted, but it may not always bend toward justice – or freedom, for that matter. Pfeiffer’s dynamic disruptions of time enable us to see this. In both literal and metaphorical miniature, Pfeiffer’s titular work dramatizes how freedom is felt – or not – by those who are promised freedom but never see it, those whose lands were never ceded, whose treaties have historically been disregarded, whose freedom papers were torn apart or burned, or whose promise of 40 acres and a mule was never realized. Pfeiffer’s two-channel video comically enacts what it feels like – to use what are perhaps apt sports metaphors – to have the goalposts shift or the finish line move, as soon as the dream seems within reach. This is the loop in which many of us live. And it may be not merely a bug but a feature of freedom’s project.

“Paul Pfeiffer: Prologue to the Story of the Birth of Freedom,” Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), Los Angeles, November 12, 2023–June 16, 2024.

Peter L’Official is an associate professor of literature and director of the American and Indigenous Studies Program at Bard College. He is the author of Urban Legends: The South Bronx in Representation and Ruin (Harvard University Press, 2020), and his writing has appeared in Artforum, Architectural Record, the Atlantic, the New Yorker, and other publications. He is an editor at the European Review of Books, and he is at work on his next book on the intersections between literature, architecture, and Blackness in the United States.

Images credit: 1. © Paul Pfeiffer, courtesy of Paul Pfeiffer, Paula Cooper Gallery, carlier | gebauer, Perrotin and Thomas Dane Gallery, photo Christian Capurro; 2. + 3. Courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), photos Zak Kelley

Notes

| [1] | “Paul Pfeiffer and John Baldessari in Conversation,” in Paul Pfeiffer, exh. cat., ed. Paul Pfeiffer, Dominic Molon, and Jane Farver (Chicago: Museum of Contemporary Art; Cambridge, MA: MIT List Visual Arts Center, 2003), 34. |

| [2] | Stephanie Smallwood, “Freedom,” in Keywords for American Cultural Studies, 2nd ed., ed. Bruce Burgett and Glenn Hendler (New York: NYU Press, 2014), 111. |

| [3] | Ibid., 115. |