THE MESSENGER IS THE MEDIUM Pamela M. Lee on Jack Whitten at the Museum of Modern Art, New York

“Jack Whitten: The Messenger,” Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2025

The title of the revelatory Jack Whitten retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, “The Messenger,” begs the question: What, ultimately, is the message being delivered here, the code deployed? [1] What larger imperatives underwrite a career marked by relentless experimentation in abstraction and an abiding commitment to the interests of Blackness? Organized by Michelle Kuo, MoMA’s chief curator at large, the exhibition follows Whitten’s development from the 1960s to his passing, and from Alabama to New York to Crete, where his family summered annually. Viewers broadly familiar with his work will be struck by the artist’s exacting technique across media including painting, sculpture, drawing, and mosaic work. “The Messenger” more than satisfies MoMA’s track record of rigorous monographic surveys, making an unimpeachable case for Whitten’s contribution to postwar painting.

But it would be a mistake to reduce the show’s achievements to a gesture of canon-building, imperative as that is. Indeed, the exhibition is emblematic of what Kobena Mercer calls “discrepant abstraction,” work that does “not neatly fit into the institutional narrative of abstract art as a monolithic quest for ‘purity.’” [2] As Whitten was an abstract painter emerging at a time when the Black Arts Movement championed figuration, his seeming outlier status no doubt deserves the expansive treatment it is given here. Still, we should take seriously the dynamic between message and messenger in the exhibition’s title, even while seeking to avoid reproducing age-old conventions dividing “form” and “content” or “medium” and “message” – that is, the formal dimensions of abstraction versus Whitten’s experience of the Jim Crow South. Whitten’s art, rather, might be considered a sustained chronicle of Black techne, in which the knowledge suggested by the term mediates and alchemizes a range of sources – photography, abstraction, jazz, New York urbanism, African carving traditions, minimalism, textiles, and ancient Greek art. “The Messenger” is as much about technology and Blackness as it is a meticulously staged paean to an artist due greater recognition.

Jack Whitten, “Birmingham,” 1964

Dedicated to Whitten’s work during the 1960s, the introductory gallery showcases the artist’s then-emerging dialogue with abstraction and media. Surprisingly, the exhibition’s inaugural work dates not from this period but from 1994. Black Monolith II (Homage to Ralph Ellison The Invisible Man), taken from the eponymous series that appears later in the show, appears relatively modest. A mosaic of hundreds of hand-cut acrylic tiles presents a fragmentary outline of the titular figure, free of any identifying details. A barely visible razor blade lies at its center, suggesting the knife’s-edge stakes at play in processes of racial formation. Ellison’s 1952 novel referenced in the title thematizes questions of visibility and invisibility as a subterranean politics for Black subjects, for whom notions of “fugitivity” – a key word in Black Studies – are paramount. “The Messenger” follows suit.

Indeed, Black Monolith II stands as a message from the future in relation to earlier works. Birmingham (1964) is an intimately scaled collage consisting of a blackened painted foil support, punched through from behind to reveal a degraded newspaper photograph of a Civil Rights demonstration erupting into state-sponsored violence. The Head series (1964–66) consists of ghostly white images made by scraping acrylic paint onto a black plane. Whitten layered canvases with paint before pressing a fine mesh on top of them, surfacing some of the medium; he would then scrape and drag this excess paint across the mesh, resulting in shadowy traces that recall blurred photographs. The title of one work refers to victims of racial terror, but the decidedly nonfigurative quality of the paintings resists the ways in which the visual field might traditionally capture their representations. Confronting these histories without literalizing them, Whitten implicitly reckoned here with photographic reproducibility and the relatively new medium of acrylic paint, technologies that would go on to preoccupy him for decades.

The next galleries underscore this experimental orientation. Whitten stopped using paint brushes in 1970, abandoned figuration, and subsequently described his work using the rhetorical framework of a laboratory. Critical to this shift was “the Developer,” a rake-like instrument that he pulled across canvases layered thickly with acrylic. Kuo gives the tool a prominent place in the exhibition, registering its catalytic impact for Whitten’s painting while also flagging the intermedial dimensions of his art. Minimalist in its construction, this 40-pound object demanded extraordinary precision to drag it across the paint in one continuous sweep. The effects produced are in abundant evidence, in paintings that evoke the sense of an image in transmission, such as Mirsinaki Blue (1974). By naming the tool “the Developer,” Whitten thematized the mechanical dimensions of his enterprise in a way that metaphorically chimes with the reproductive logic of photography.

Of course, Whitten’s technical preoccupations were also in tacit dialogue with Black artist contemporaries who were pursuing their own distinct agendas. [3] If mainstream art history has long marginalized abstraction by these artists, it has, with notable exceptions, also failed to address their contributions to narratives of art and technology. (The legacies of Afrofuturism in music, performance, and film provide an important counterpoint to such art historical tendencies within Black Studies.) For his part, Whitten’s engagement with the material science of acrylic paint, which was patented in the 1920s and reformulated by Leonard Bocour in 1945, might be misrecognized as a Greenbergian exercise in medium specificity. But Whitten’s obsessive retooling of acrylic’s plastic possibilities, in order to introduce new formal procedures with decisive implications for questions of race, visibility, and invisibility, ran counter to such essentialism.

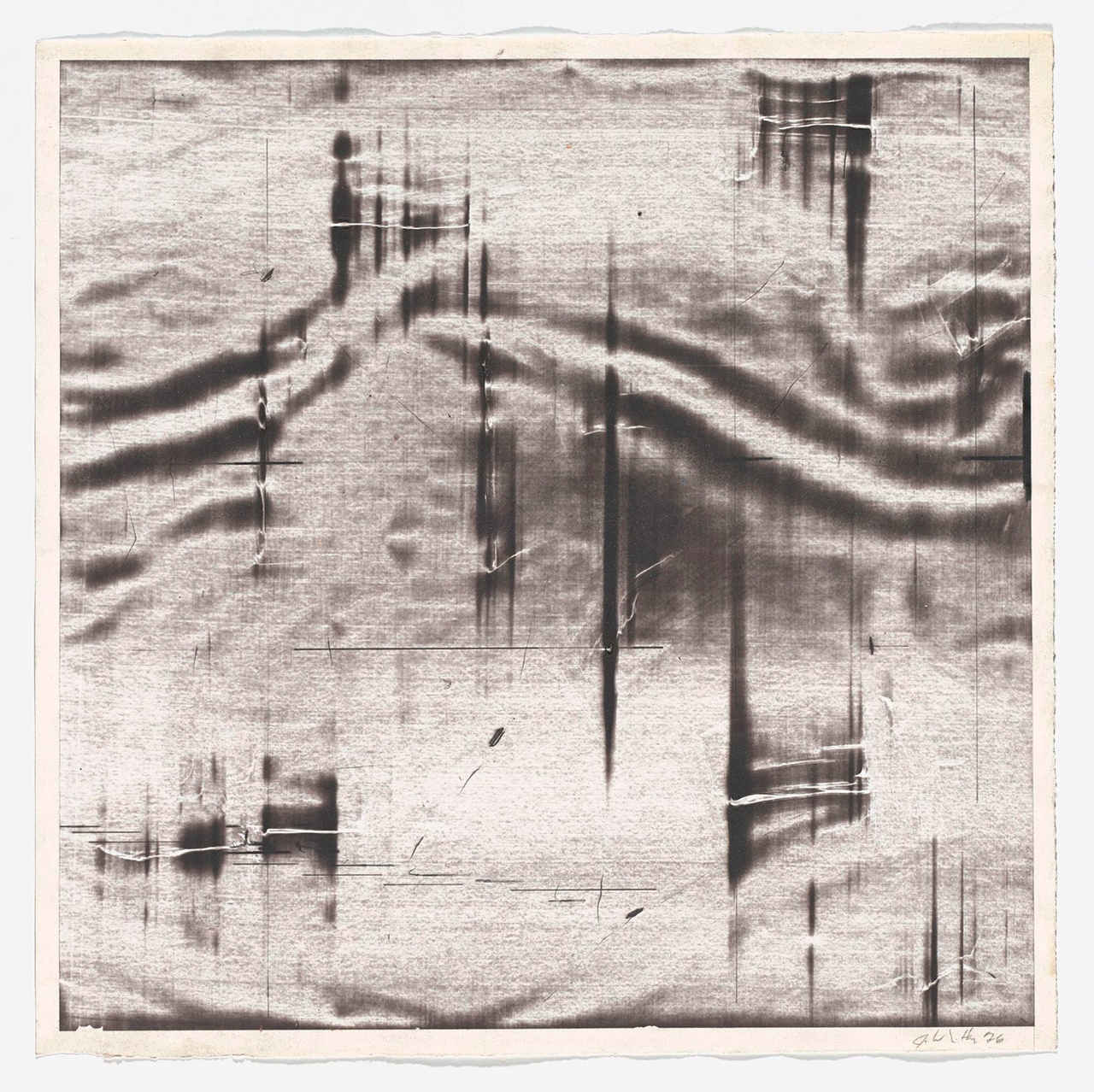

Jack Whitten, “Liquid Space I,” 1976

This inventiveness was on full display in the mid-1970s, when Whitten all but abandoned color for a few years. The Greek Alphabet series and related experiments with Xerox copier toner (Whitten was an artist-in-residence at Xerox’s headquarters in Rochester, New York) are among his most startling achievements, in spite or perhaps because of their limited palette. Sigma IV (1977–78) is as exacting in its geometry and rigor as it is destabilizing in its impact: It may seem to register as an immediate gestalt, but closer inspection troubles any sense-certainty about Whitten’s process, application of media, or compositional choices. Indeed, the work’s vibrational intensity renders it difficult to take in after a few minutes; here, black and white do not easily parse. (For Whitten, such formal experiments inflected questions of racial formation – the effective dissolution of dualities of black and white.) Meanwhile, Liquid Space I (1976) is a remarkably complex abstract drawing in which the paper substrate is manipulated in such a way as to confuse relations of figure and ground, and no less designations of medium. Its simultaneously aqueous, spectral, and holographic quality recalls his earlier Head series in its uncanny, near-photographic appearance.

Whitten continued his media experimentation in order to avoid illustrating Blackness, instead materializing its myriad forms as shifting visual propositions. Kuo punctuates the exhibition with the artist’s lesser-known sculptural works, including objects that reference African carving traditions, modernist sculpture, and personal effects. The rest of the Black Monolith series is presented in one of the show’s last galleries, as a pantheon to towering figures of Black politics and culture that concedes little to representation in the sense of portraiture. Whitten’s use of mosaic in his final years owes a debt to both his painstaking innovations in acrylic (each tile is hand-cut) and his decades-long engagement with ancient art. And yet, not only: Here, references to the computer also enter the scene, only for Whitten to torque its communicative possibilities. Apps for Obama (2011) deploys the tiles as if to draw connections between these fragmentary units, as ancient carriers of visual information, and the pixels and bits of the emergent digital age.

In “Technology and Ethos” (1970), Amiri Baraka wrote of the ethical, political, and creative possibilities of technology for Black people: “Nothing has to look or function the way it does.” [4] Baraka’s association with the Black Arts Movement puts him at a distance from Whitten, but his words still resonate powerfully in the context of “The Messenger.” A communicational directive drives Whitten’s coalescence of media, materiality, technology, and history, but to what end? Refuting both the easily graspable image and the idea that technology is supposed to function in a particular way, he registers processes of transmission as representative of abstraction’s endless plastic possibilities.

“Jack Whitten: The Messenger,” Museum of Modern Art, New York, March 23–August 2, 2025.

Pamela M. Lee is Carnegie Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art in the Department of the History of Art at Yale University.

Image credits: 1. photo Jonathan Dorado; 2. courtesy the Jack Whitten Estate and Hauser & Wirth, photo John Berens; 3. © The Museum of Modern Art, New York, photo Peter Butler

Notes

| [1] | It is in part named for Whitten’s tribute to the jazz trailblazer Art Blakey as a “messenger.” |

| [2] | Kobena Mercer, introduction to Discrepant Abstraction, ed. Kobena Mercer (Institute of International Visual Arts; MIT Press, 2006), 8. |

| [3] | Ed Clark elaborated his “push-broom” approach to abstraction in the late 1950s; Fred Eversley, Tom Lloyd, and Charles Gaines brought engineering and computer expertise to their work in the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s. |

| [4] | Imamu Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones), “Technology and Ethos,” in Raise, Race, Rays, Raze: Essays Since 1965 (Random House, 1971), 54. |