DARK MIRROR Sasha Rossman on Vija Celmins at Fondation Beyeler, Basel

“Vija Celmins,” Fondation Beyeler, Basel, 2025

In the 1980s, art historian Svetlana Alpers dubbed Dutch art of the 17th century an “art of description” in her pioneering book of the same name. [1] Dutch images from this period, she argued, ought to be understood not as paintings and drawings of things themselves but rather in terms of processes of observing and describing. A work like Johannes Vermeer’s canonical View of Delft (1660–61), according to Alpers, is not so much a view of the city but a description of how the city might have been seen through the viewing instrument of the camera obscura, or as a collated set of pictures that appear on the eye’s retina. Works like Vermeer’s, or Dutch still lifes, are for Alpers thus an art primarily interested in processes of visual perception and recording. Vija Celmins has discussed her own work not only in terms of description but even more resolutely as redescription, or “that kind of double reality, where there’s an image, but the image is here in another form … interwoven with that surface.” [2]

The artist’s retrospective at the Fondation Beyeler begins chronologically, with paintings made in Los Angeles in the 1960s of quotidian objects such as lamps, glowing heaters, or hotplates in her studio. These lead to Celmins’s trademark drawings and later paintings of photographs depicting the ocean or desert, moon or deep space. Across the decades (the artist’s career spans six) and also media (aside from paintings and drawings, the show includes prints and sculptures), her work manifests an obsessive engagement with – as Alpers argued about Dutch art – observing and redescribing entities that are sometimes nearly impossible to see. Or rather, representing the mechanisms through which humans attempt to bring the unseeable, or overlooked, into view.

Celmins’s eye and hand attend to every nuance of her mostly photographic source material. In the beginning, her redescriptions took the form of graphite drawings or prints made from labor-intensive techniques like mezzotint or wood engraving, which represented the description already displayed by her source photographs as a dizzying array of details rendered in a new medium. These were examinations that materialized the process of looking as an act of making, a theme present in even her early studio still lifes of objects like lamps or heaters. Unlike the works of her West Coast pop contemporaries, who were also interested in the lives of consumer goods, Celmins’s still lifes are subdued and functional. These paintings do not deconstruct popular culture but rather reproduce the artist’s working conditions – light and warmth. In subsequent works, Celmins turned to photographs, often from magazines, whose surfaces she redescribed, as opposed to observing objects directly from life. The step to photography as a source provided a layer of distance, enabling her to dispense with obvious marks of individual authorship, such as biographical or gestural traces. By the 1970s, Celmins turned to microscopic details (of stones, for instance) and the interminable vastness of outer space and the sea, which seem devoid of compositional elements other than an overwhelming amount of exacting information.

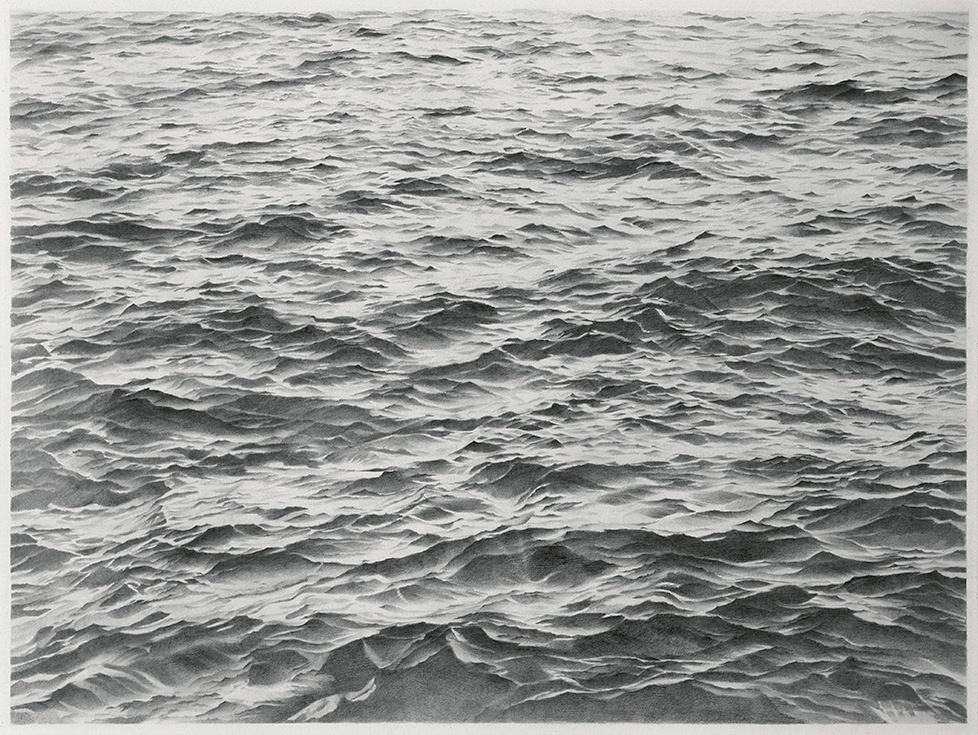

Vija Celmins, “Untitled (Big Sea #2),” 1969

Having dispensed with narrative, gesture, and frequently composition through the selection of her source material, the artist directs the viewer’s eye to scan the many details that she has redescribed so that they can be inspected and attended to in a different manner than how one usually assesses such images. The arbitrariness of the indexical trace transforms into a forest of deliberate marks, as in Untitled (Big Sea #2) (1969), where every nuance of each wave of the Pacific captured by Celmins in Venice Beach becomes a trace of the artist’s pencil. The attention devoted to each graphite smudge, which is synonymous with each subtle wave, compels the viewer to take in the image slowly, one bit at a time. As in a 17th-century Dutch painting, such as the View of Delft, these are images (or sometimes sculptures) that still a world in flux and present a picture not as a window onto the world but rather as a (heavily) mediated description.

In the 1974 drawing Untitled (Desert – Galaxy), Celmins presents two redescriptions side by side, juxtaposing a desert surface with an image of a distant galaxy. The desert is in a smaller rectangle. Its intricate surface was made by building a light acrylic ground and then adding an infinite number of shadows in the form of small graphite marks to define each tiny pebble. The larger rectangle of outer space next to it was made in the opposite manner: The white ground was covered in graphite, and the stars and planets were then made from eraser marks, so that they appear to emerge from the darkness as points of light. Modes of redescribing a photographic description are displayed here as inversions of one another but put to no ostensible purpose. There is no horizon to position the viewer, no intention, and no story, or allegory, to unravel. There is just a doubling, perhaps a twinning, of information created through sustained methods of addition and subtraction.

Much writing about the artist has dwelled on the role of temporality in her work: It takes Celmins a long time to make these intensely rendered objects, just as they challenge the viewer to spend a long time looking at them. The plethora of details can be nearly overwhelming; we cannot grasp them all at once, so our focus must probe every little star, wavelet, or face of a rock. Looking becomes a process of inspecting and thus remaking through our gaze that scans a surface of manually redescribed data. The artist’s hand is present, but the artist herself is distant and almost entirely removed as a subject, just as her redescriptions do not directly acknowledge the viewer even as they ask us to look at them. Celmins’s surfaces are quite indifferent to us in the same way that space, or the ocean, or the desert is indifferent to us: They steadfastly deny our importance and challenge us to deal with our irrelevance in the face of their vastness and a temporality that far exceeds our own, as some writing on her work has noted. [3] Understood in this way, these works are not simply about the time spent making them; they also articulate a subject-object relationship in which a kind of redemptive human individuality is undermined by redescription.

An early sculptural work perhaps hammers home this point in a different way than the images of natural phenomena do. Pencil (1966) is a deadpan redescription of a gray pencil enlarged to over a meter long. Made of wood but covered in canvas and then painted, the object is pointy but has no obvious point. Its conspicuous inertness, too large to pick up and use, indicates a derailing of the maker. We find ourselves in a maze of paradoxes: Agency and causality are negated while making is affirmed; large things become small, and small things become giant; the very far away is also very close-up; information is plentiful but entirely mute; the minimal is abundant; erasure signifies appearance; and the artist is present although absent – as in her Letter, (1968) which presents a trompe l’œil rendering of an envelope addressed to Celmins from her mother. We read the artist’s name, but the information reveals nothing other than another surface for the eyes to scan. The envelope’s fictitious but entirely convincing stamps are emblazoned with mushroom-cloud-like explosions rendered softly in delicately shaded graphite.

Vija Celmins, “To Fix the Image in Memory I–XI,” 1977–82

One sociohistorical context that provides a direct parallel to Celmins’s career – and her images of the night sky specifically – is the Cold War space race, with its attempts to master and colonize on an interplanetary and even intergalactic scale. In the late 1960s, alongside her images of bomb testing, such as Bikini (1968), Celmins began to make drawings of photographs of the moon’s surface taken by Luna 9 and other Soviet probes and, later, of images by NASA. The technological development at the time engendered not only photographs of far-off galaxies or lunar surfaces but also the creation of a specific type of doubling that can be put into dialogue with Celmins’s redescription, particularly during her prolonged engagement with space images: the creation of digital twins. The digital twin is a virtual model that mirrors a physical entity based on a feedback loop that funnels data into a simulation. This double, in turn, operates as a means of producing knowledge not firsthand through direct observation but through observation of the digital twin’s representation of this data. NASA has claimed that the first digital twinning technology was set up in the context of the 1970 Apollo 13 mission, in which a feedback loop connected live images from outer space to a simulation on earth to assess risk and to develop potential solutions. In the world of the digital twin, causality is dispensed with since data presents itself purely as fungible information to be optimized.

Celmins’s redescriptions, meanwhile, are more recalcitrant. Like digital twins designed to predict meteorology, they are also preoccupied with weather (clouds, falling snow). Yet the artist’s redescriptive twins counter any kind of productive operationality. Her doubles are decidedly anti-productive, unlike the Dutch art of description that, similar to digital twins, tended to celebrate data synthesis in the service of capital. Celmins’s works are noncausal, but they do not feign to deny intent. It took the artist five years to finish To Fix the Image in Memory I–IX (1977–82), which consists of nine rocks and their doubles: bronze casts of the rocks painted to look exactly like the originals. Inspection leads only to undirected fascination, or frustration.

There is something decidedly non-ironic in this practice. If there is a political critique to be deciphered, it expresses itself obliquely. Perhaps this is why Celmins’s work appears to have been barely received in the German-speaking world. Her last exhibition in Switzerland took place nearly 30 years ago. In Germany, Hamburg’s Kunsthalle exhibited her alongside Gerhard Richter in 2023, but Celmins’s works have by no means been as widely embraced as Richter’s as a practice of redescription. The majority of loans at the Beyeler come from the United States, where MoMA and other major museums own numerous pieces. Although Celmins’s works offer no typically American “happy end,” they employ popular postwar cultural touchstones related to vast spaces: deserts, oceans, and galaxies and their attendant postwar fictions of never-ending growth, optimization, and self-realization. Do these tropes and her earnest, indirect mode of address make Celmins’s practice less palatable to a non-US audience? While earnest, her objects are, however, also deceptively sneaky. Like a spider’s web, another of her favorite motifs, her work catches its prey (the viewer) unaware. Drawn in by the power of verisimilitude, we find ourselves trapped by the realization that Celmins’s remarkable redescriptions offer a surface, or mirror, in which we, if not the artist, are deeply lost.

“Vija Celmins,” Fondation Beyeler, Basel, June 15–September 21, 2025.

Sasha Rossman is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Bern’s Institute for Art History.

Image credits: all courtesy © Vija Celmins, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Notes

| [1] | Svetlana Alpers, The Art of Describing: Dutch Art of the 17th Century (University of Chicago, 1983). |

| [2] | Vija Celmins quoted in James Lingwood, “The Impossible Image,” in Vija Celmins, exh. cat., ed. Theodora Vischer and James Lingwood (Hatje Cantz; Fondation Beyeler, 2025), 16. |

| [3] | For example, Max Kozloff, “Vija Celmins,” Artforum 12, no. 7 (March 1974): 52–53. |