TOWARD CRITICISM AS AN ANECDOTAL SCIENCE “Pictures, Before and After: An Exhibition for Douglas Crimp” at Galerie Buchholz, Berlin

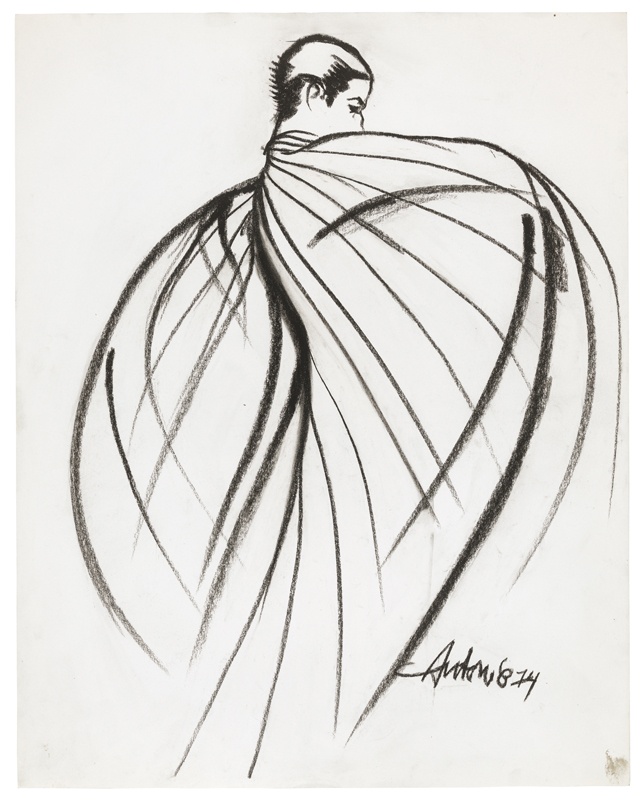

Antonio Lopez, „Charles James Ribbon Cape Drawing 1", 1974

Widely influential as an art historian, writer, and activist in his native New York and beyond, Douglas Crimp, on the occasion of his 70th birthday, was the subject of an exhibition and symposium this fall in Berlin. It would be easy to simply praise the effort, which indeed was at once sweeping – featuring work from the 1960s to the 1990s – and highly specific, including several rarely (if ever before) seen pieces that came into Crimp’s world via the scenes in which he has participated and that his writing deeply involves. How to address a career such as Crimp’s, which is predicated on the power of critique? Here, Philipp Ekardt considers the many channels across which Crimp has been active, focusing in particular on the risks and, in this case, necessity of the writer’s offering up of moments not just from his work, but from his life in the public forum.

In writing about “Pictures, Before and After: An Exhibition for Douglas Crimp,” held at Galerie Buchholz, and the parallel symposium at the Arsenal Institut für Film und Videokunst, one faces a genuine challenge. One has to fight the temptation of wanting to simply join the choir of voices, the orchestra of critical and artistic positions that were assembled on this occasion to document and – not to shy away from some gravitas at the beginning – to honor Douglas Crimp’s achievements on the occasion of his 70th birthday. The urge to simply partake in the celebration is strong. After all, Crimp curated what is arguably one of the most central art exhibitions of the second half of the 20th century – “Pictures,” held in 1977 at New York’s Artists Space, which formulated the problem of appropriation in art for the first time in the most concise sense of the term. He also served for more than a decade as an editor of one of the most influential journals for contemporary and modern art, theory, and criticism, namely, October.1 And he is rightly known for his political work as an activist in the battle against AIDS/HIV, and against the criminal disregard, in the United States, initially (and partly still) brought by governments and administrations to those afflicted by the disease. This resulted in one of that movement’s landmark publications – the 1988 anthology “AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism” and in one of the most pertinent recent pleas for an immediately political understanding of art, insisting, as Crimp famously does, that “art saves lives,” when he talks about artists’ contributions to the ACT UP movement.2 Thus, how not to simply celebrate Crimp, who, as it happens, is also a first-hand connoisseur of the underground (filmic) œuvres of Andy Warhol, Jack Smith, and Mario Montez; as well as a pioneering voice regarding the intersection of visual art and dance? Why not simply just say yes to almost everything he’s done in all of those fields? Because mere affirmation is, if not always false, certainly always boring, and the least criticism can do is to differentiate and try to analyze what’s good. Setting up the exhibition, Diedrich Diederichsen, Juliane Rebentisch, and Marc Siegel – who also organized the symposium – and their collaborators at the gallery, resorted to Crimp’s most recent work, taking chapters of his forthcoming memoir “Before Pictures,” which covers the decades of the 1960s and 1970s as a guiding structure. The show included proleptical movements into the fights of the 1980s and progressed by periodization, taking its cues more or less directly from the book. Passages from each chapter and the short time-periods to which they referred served as starting points for the different sections. These cues were concretely present in the gallery as wall text, brief excerpts that replaced the full-length chapters with (sometimes juxtapositions of) a few paragraphs that defined the thematic spectrum of what was on view. Take, for example, the chapter “Way Out on A Nut,” in which Crimp recounts the story of his (professional) beginnings in New York City: The official narrative is that upon arriving from Tulane University he joined the Guggenheim Museum where he worked as a curatorial assistant on the realization of Daniel Buren’s “Peinture-Sculpture” contribution to the 1971 Guggenheim International exhibition; a work that, in an art historic scandal, was removed before the show even opened. The memoir – and with it the wall text – now furnished an additional piece of information: that Crimp’s first New York job was actually as an assistant to Charles James, the United States’ foremost, and perhaps only couturier, the inventor of the clover dress, whose clients included everybody from Lee Radziwill to Gloria Swanson, and whom Crimp was (unsuccessfully) supposed to assist in organizing his notes toward a memoir. In the show, such biographical constellations spawned an intriguing assembly of objects and images. Two oil pastels of Charles James’s Ribbon Capes, executed by the iconic fashion illustrator Antonio Lopez, were placed on the wall. In two adjacent vitrines, an installation view of Buren’s work in situ was combined with samples of the fabric of which the piece consisted; these samples were Buren’s catalogue contribution, whose execution Crimp had overseen. The rest of the vitrine was taken up by photographs of the Houston home of the collectors de Menil, built by Philip Johnson, its interior designed by James. A catalogue from James’s 1982 show at the Brooklyn Museum, including reproductions of those Antonio works on paper that hung on the wall, completed the ensemble. In addition to biographical and historical coincidence, the items on display communicated with each other on the level of form and media. Antonio captured James’s capes as elegantly bulging expanses of slashed textile, visually structured with gracefully curving sets of stripes. At Buchholz, that impression stood against the steep vertical drop of Buren’s trademark stripes. The medium of textile here connected the worlds of fashion and its illustration on the one hand, and the realm of proto-conceptual art on the other hand, where it had replaced the canvas. Facing such interconnections, it was as if coming across a collection of materials toward a better art history. Where are the articles, lectures, and shows that explore exactly such trans-material, trans-medial, trans-social trajectories? While that feeling persists, analysis kicks in and one wonders about the validity of such interconnections beyond this particular occasion, on which they are justified and stunning. Is there a common denominator here, beyond that one-work biography? Another case in point was a section in the exhibition that cut across two rooms. Congregating roughly around an excerpt from the chapter “Action Around the Edges,” already published in an earlier version in the exhibition catalogue for “Mixed Use Manhattan” (a show that Crimp cocurated with Lynne Cooke for the Reina Sofía, Madrid), are a number of filmic and photographic works, including documentary and artistic practices, that explore the urban territory of Lower Manhattan. This section looked back at Joan Jonas’s 1973 16 mm film “Songdelay,” shot with wide-angle and telephoto lenses on the roofs of Manhattan, collapsing the space between the inner city and trans-Hudson Jersey into a flat picture. It included two dry and pared down nighttime shots of deserted streets by Peter Hujar; Gordon-Matta-Clark’s 1975 Super 8 film “Day’s End,” which showed one of his characteristic incisions into a warehouse on the downtown piers; and a series of pictures by Alvin Baltrop, who also documented the piers, but in their function as New York’s famous queer cruising grounds, in a combination of derelict architecture and men of many races and ages having sex.

„Pictures, Before and After – An Exhibition for Douglas Crimp”, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin, 2014, installation view

What emerged here was a cohabitation of otherwise only remotely connectable social, aesthetic, and artistic practices, just as in the case of Buren, James, and Lopez. There may have been many more observers who registered such coexistence of protagonists and places at the time. But Crimp seems to be one of the few who refused self-policing and began to put that coexistence into his writing and curating. Such gestures may account for the power of what’s on view here. A few paragraphs into “Action Around the Edges,” Crimp explains that his 1974 “move from the Village to Tribeca came about as a result of my decision to get serious about being an art critic, to replace the gay scene with the art scene […] I’d come to feel myself adrift, not accomplishing enough, not spending enough time with the crowd to which I ‘rightly’ belonged.” An attempt that, he explains, “was destined to fail.”3 What Crimp here so nonchalantly declares is that to be a failure is to experience success. It is the refusal to give in to that silent imperative that, in order to accomplish what’s valid, one thing must make room for another; that belonging to the “right” crowd entails leaving the ostensibly wrong one. The same holds true for what can be considered “valid” subject matter for serious criticism. In pretending to fail to trade the “gay crowd” for the “art crowd” Crimp refuses the directive of such an exchange; he also rejects the assumption that these are commensurate exchangeables. Validation and recognition cannot be derived from disciplinary authority if the latter builds on the logic of the sacrifice and purification. Discussing, at the symposium, the early films of Andy Warhol (the subject of one of Crimp’s studies), Diedrich Diederichsen succinctly decoded that book’s title “Our Kind of Movie” as referring to the “early symptoms of a genre.” In the absence of an exterior formal determination, these films were defined as belonging together through the shared preference of a certain social group, and in this constellation something like a common descriptor began to emerge. This, Diederichsen underlined, corresponds to the “political power of the proto-” in Crimp’s work.4 The insistence on the proto-, on that which is nascent, not yet valorized, may never be, seems to contribute to the transversal productivity that is to be witnessed here. It is also what sets Crimp’s work apart from that of some of his peers and colleagues who busily developed postmodernism through criticizing the grand narratives of modernism, while in this agonistic mode of critique, implicitly resurrected the principle of criticism-as-struggle. Crimp, by contrast, simply left, or took things elsewhere; or, as he confesses, he might have failed, but in leaving, failed productively. Does his work give us a theory of how to do that? Not to this writer’s knowledge. And are the suggested trajectories and interconnections always convincing? Not necessarily. For instance, one room in the exhibition, deriving from the chapter “Agon,” pulled together references to George Balanchine; Crimp’s colleague and friend Craig Owens who introduced him to ballet; a vitrine dedicated to Fassbinder; and all this was prefaced with a short and beautiful passage describing how Crimp, when pulling out his copy of Derrida’s “Of Grammatology,” comes across a note for which seats to buy at the ballet, as recommended by Owens. How the ur-text of deconstruction can have a more than ornamental value in this juxtaposition of dance, Neuer Deutscher Film, two gay critics and a gay director, is unclear, even if one takes into account that Owens was one of the first authors to champion poststructuralism in the field of the arts. But one such occasional non sequitur doesn’t discredit the project. As far as can be told at this point, the way in which the history of this type of work will be written, including the manuscript for this memoir, will rely centrally on the form of the anecdote; an often falsely disregarded genre. Not only is Crimp a masterful teller of anecdotes,5 it is also the anecdote that best captures the interweave of biography and work, of everyday encounters with moments in the arts, the very incidental structure that seems one of the crucial factors behind how Crimp works and thinks; and a factor on which the exhibition consequently capitalized. Fully realizing the incidental nature of the anecdotal, the co-incidences Crimp recounts are far from trivial. In its original Greek meaning, the term anecdote referred to a not-yet public event, to something that has occurred in the shadow of the grand narratives, so to speak, and still awaits telling.6 The anecdote, then, is the ideal mode of articulating that “proto-” Diederichsen mentioned: an emergent, contingent quality in something that could, from the vantage point of disciplinary discourse, be mistaken for mere happenstance. It is the form for speaking about that which attracts out of interest, rather than by legitimacy; for telling future counter-histories. Such as the ones we find in Crimp’s life and work. Philipp Ekardt

“Pictures, Before and After: An Exhibition for Douglas Crimp,” Galerie Buchholz, Berlin, August 28–October 31, 2014.

Notes

| [1] | journal – to speak pro domo – without whose example, it is safe to say, the initial years of Texte zur Kunst would have played out differently. |

| [2] | Crimp’s article “How to Have Promiscuity in an Epidemic, included in “AIDS. Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism,” also offered one of the most articulate and sustained condemnations of the false moralizing treatment that those afflicted had to endure; in the light of the recent debates concerning PREP-medications, such as Truvada, its arguments are perhaps worth revisiting. |

| [3] | Douglas Crimp, “Action around the Edges,” in: Mixed Use, Manhattan. Photography and Related Practices, 1970s to the Present, ed. by Lynne Cooke/Douglas Crimp, with Kristin Poor, Madrid/Cambridge, Mass./ London 2010, pp. 83–129 (84). |

| [4] | This assessment relates back to a previous collaboration between Crimp and an extended group, among them the exhibition’s and symposium’s organizers, which explored the concept “cross gender – cross genre.” The corresponding catchphrase on the level of identity politics, also issued by members of that group, or rather: the corresponding rejection of a false demand to “identify” would have been to explore that what was, or is “queer before gay,” see: Golden Years. Materialien und Positionen zu queerer Subkultur und Avantgarde zwischen 1959 und 1975, ed. by Diedrich Diederichsen/Christine Frisinghelli/Christoph Gurk/Matthias Haase/Juliane Rebentisch/Martin Saar/Ruth Sonderegger, Vienna 2006. |

| [5] | For those present at the symposium and for future readers of the memoirs, the name Ellsworth Kelly will, thanks to a Crimpian anecdote that shall not be retold at this point, forever be associated with the term shrimping … |

| [6] | The theory of anecdotal speech here only alluded to will profit enormously from the work that is currently being done by Dirck Linck in the context of his research on Hubert Fichte. I am very grateful to Dirck for sharing with me the manuscript for his lecture “Klatsch und Anekdote,” held at the Free University Berlin in May 2013. |