AGAINST AFFIRMATION Alice Blackhurst on Jesse Darling at Modern Art Oxford

“Jesse Darling: No Medals No Ribbons,” Modern Art Oxford, 2022, installation view

Painted in cheery bureaucratic yellow on the stairs leading to “No Medals No Ribbons,” Jesse Darling’s solo exhibition currently on view at Modern Art Oxford, are the words “Take care/Keep your distance.” A stark trace of the ongoing pandemic, this conflicting couplet of instructions feels an apt container for Darling’s dialectical and heterogeneous work. Darling’s art, drawing equally on found, everyday materials and high-register critical theory, both encourages spectators to come closer and, via layers of complex mediation, keeps them at arm’s length. If it wasn’t so conceptually and formally enrapturing, it might be a slightly maddening experience: a cat-and-mouse game torn between the desire to cultivate interdependency and the need to draw boundaries and self-protect.

The exhibition is a broad-ranging survey of the past decade or so of Darling’s art, which has included their group and solo work in Paris, Freiburg, Tate Britain, and the Venice Biennale. The title is, in the artist’s own defiant words, “a repudiation of the whole triumphant ‘retrospective’ thing,” which tends to reify the figure of the artist as commodity or lofty genius. [1] More covertly, it is also a reference to a distant relative of Darling’s, who, while a prisoner during the Second World War in Germany, made over 300 artificial legs for fellow injured inmates from whatever materials he could hide from guards, yet after the conflict, refused trophies and other forms of affirmation, preferring to draw a line under “what happened” and move on. [2] “Though I think a lot about history,” Darling has echoed, “I would rather forget my own.” [3]

Jesse Darling, “Gravity Road,” 2020

The exhibition’s non-chronological, zigzagging layout is informed by a resistance to the progress narratives of conventional career surveys; instead, it is an exploration of the more recursive and disjointed practice of artmaking – what scholar Alison Kafer, in connection with the labile temporality of disability, calls the queerer permutations of “crip time.” [4] Studded with mythological reference points, as well as bodily prostheses and waste materials from our overcrowded and overconsuming planet, the effect is like getting lost in Hansel and Gretel’s famous forest. Amidst this thicket of diverse media and motifs – making use of drawing, sculpture, video, and text, as Darling notably began their career as a writer – it is tempting to appoint the sculpture Gravity Road (2020), first exhibited at Kunstverein Freiburg in 2020 and modelled after a precursor to the modern roller coaster originating in 19th-century Pennsylvania, as the arguable centerpiece of “No Medals No Ribbons,” looming large in the exhibition’s first room. Tilted on its axis, and stripped of cars, the eerie steel sculpture resonates indeed as a somber meditation on the harsh processes of mining and extraction in industrial capitalist society and, more broadly, modernity’s tendency to collapse pleasure into moments of distraction and velocity. Yet on closer inspection, the viewer discovers miniature toy birds nestled at key junctures in Gravity Road’s curved steel architecture, as well as sandbags garlanded with hardy flowers such as daisies and chrysanthemums propping up the sculpture’s feet. These whimsical flourishes, in addition to offering a sense of the absurdity that freights larger-scale edifices, gesture to what Darling has called their “anti-macho,” or anti-monumental sculpture practice. [5] Privileging torqued and awkward shapes, and working with widely available, humble materials, this policy is eager to offset all narratives of the “large-scale” with minor details, flashes of levity, and moments of contingency that deviate from the straight path.

Jesse Darling, “Gravity Road (detail),” 2020

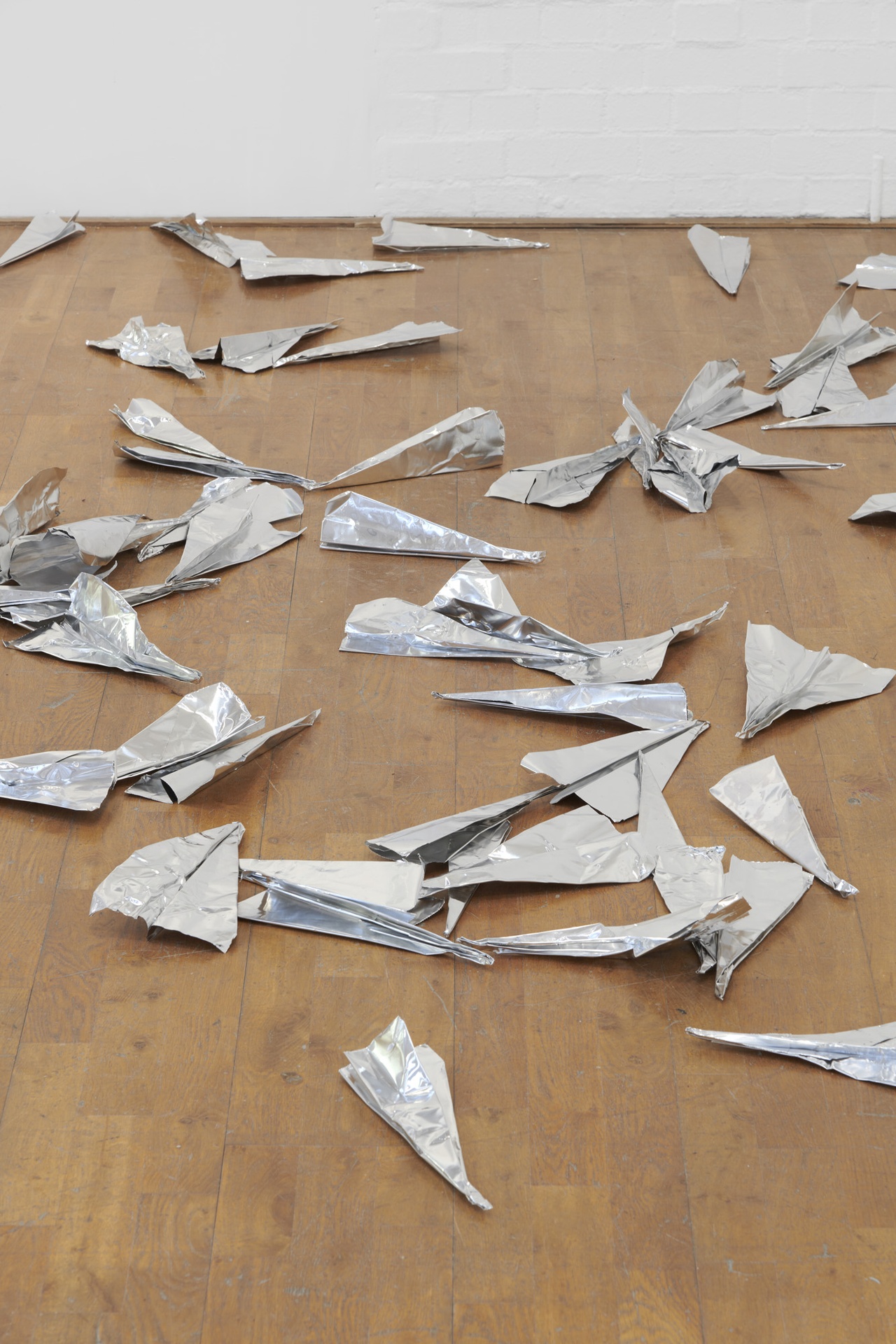

Despite the richness of its resonances and motifs, there is a strong pull in “No Medals No Ribbons” toward groundedness and stasis, of both the involuntary and elected kind. Strewn underneath Gravity Road are a glittering array of planes made of folded aluminum foil – a riff on the more commonplace and recognizable paper model, and an ironic comment on the global flight bans in 2020, when the piece was made. Works such as Collapsed Cane (2017) and Crawling Cane (2017) counter the assumed privilege of everyday mobility more directly, and tender the motifs of impairment and paralysis forefront within Darling’s art. Eschewing typical framing devices, Darling displays these works – which resemble twisted mobility canes, sprawled and splayed on the floor at Modern Art Oxford – as if someone left them there unwittingly. Their placement prompts reflection on the less-able bodies that are trampled over on a daily basis within neoliberal society’s race toward survival and success. There is also dignity in their prone status: a refusal to be linear; a refusal to conform to expectations that the disabled subject under neoliberalism “pull their socks up” and “stand on their own feet.” In Darling’s work more widely, the goal is not necessarily to “keep standing,” but to remain enmeshed and horizontal, where the more compelling intricacies and connections are.

Although it exposes widespread structures of discrimination, the exhibition is also not without playful recognition of the byzantine, kitsch signifiers that amass in contemporary bureaucratic and domestic life. Liberty Torch 1 (2016), a work combining references to tarot and US iconography, makes use of several Hitachi Magic Wand vibrators. During my own visit, one hummed comically in the background, perhaps as a sonic reminder to “work the trap,” or take pleasure where it can be found. Darling’s use of plastic throughout “No Medals No Ribbons” is shot through with similar ambivalence. On the one hand, plastic’s crassly banal, prosaic status – illustrated by the use of plastic shopping bags from TK Maxx, the UK supermarket Morrisons, and Best Buy in combination with steel poles, so such receptacles become charged and totem-like – indicates desires to subvert the lofty registers of “fine art” and to be legible outside strictly artworld circles. On the other, the defilement of plastic within Darling’s oeuvre – and its resistance to destruction – marshals a disquieting ecological statement on the indestructibility of humanmade fibers and their infinite afterlives on the earth. The series Embarrassed Billboards (2016–22) further presents two huge advertising signs with their backs to the spectator, exhausted from having to promote and sell their wares all day, their illuminated displays turned to face the wall. Encountering the work, one is reminded both of the relentless “on”-ness of consumer culture, where even after hours the lights are never dimmed, and the age-old conundrum of the artist figure, torn between, in the psychoanalyst D. W. Winnicott’s words, “the tension between the desire to communicate and the desire to hide.” [6]

Jesse Darling, “Virgin Variations,” 2019

In numerous media interviews – in which they prove a persuasive critic of their own practice – Darling has expressed reservations about the alluring traps of gender identification as a way of situating artworks. This skepticism also animates Virgin Variations (2019), a large, seductive block of wooden cabinets in the vanitas tradition of a Wunderkammer. The piece is an anti-monument of sorts to late capitalist molds of contemporary womanhood. Stationed in the final room of the exhibition, it displays quotidian trinkets and images conjuring ideas of ritual and mythmaking from mass-manufactured goods. Slotted with stickers, frayed doilies, cocktail umbrellas, torn-out photographs of Marilyn Monroe, cheap lingerie, empty wine bottles, bags for sanitary towels and fake roses, the piece tumults with what Paul B. Preciado has indexed as the codes of white heterosexual femininity and recalls the collagist practice typically indulged in by teenage girls of decorating the inside of school lockers. [7] The voyeuristic, almost queasily transparent nature of the cabinets – the intimate ephemera within them obscenely open to the viewer’s gaze – exposes how relentlessly “in public” those encased in the artificial gender of a “girl” have to live, but not without tenderness, or furtive hope that this position might incrementally be dismantled. It speaks to Darling’s wider question in their practice of how art might foster a political aesthetics of vulnerability without succumbing to the easy thrills of biography, or straightforward confession. The structure, like Gravity Road, tilts at a slight angle. The skewed nature of its exposure is precisely what invites engagement and attention. It, too, Darling seems to suggest, might fall.

“Jesse Darling: No Medals No Ribbons,” Modern Art Oxford, March 5–May 1, 2022.

Alice Blackhurst is a writer and art critic currently teaching French literature and film at St John’s College, Oxford.

Image credit: Photos Ben Westoby

Notes

| [1] | “Jesse Darling In Conversation with Curator Amy Budd,” Modern Art Oxford , February 2022. |

| [2] | Ibid. |

| [3] | Ibid. |

| [4] | Alison Kafer, Feminist, Queer, Crip (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013). |

| [5] | Saelan Twerdy, “‘Speaking from a Wound’: Jesse Darling on Faith, Crisis, and Refusal,” Momus, January 9, 2018. |

| [6] | D.W. Winnicott, Playing and Reality (London: Tavistock Editions, 1971). |

| [7] | Paul B. Preciado, Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era (New York: Feminist Press, 2013), 120. |