ELEGIAC MUSINGS Amin Alsaden on Ali Cherri at the Swiss Institute, New York

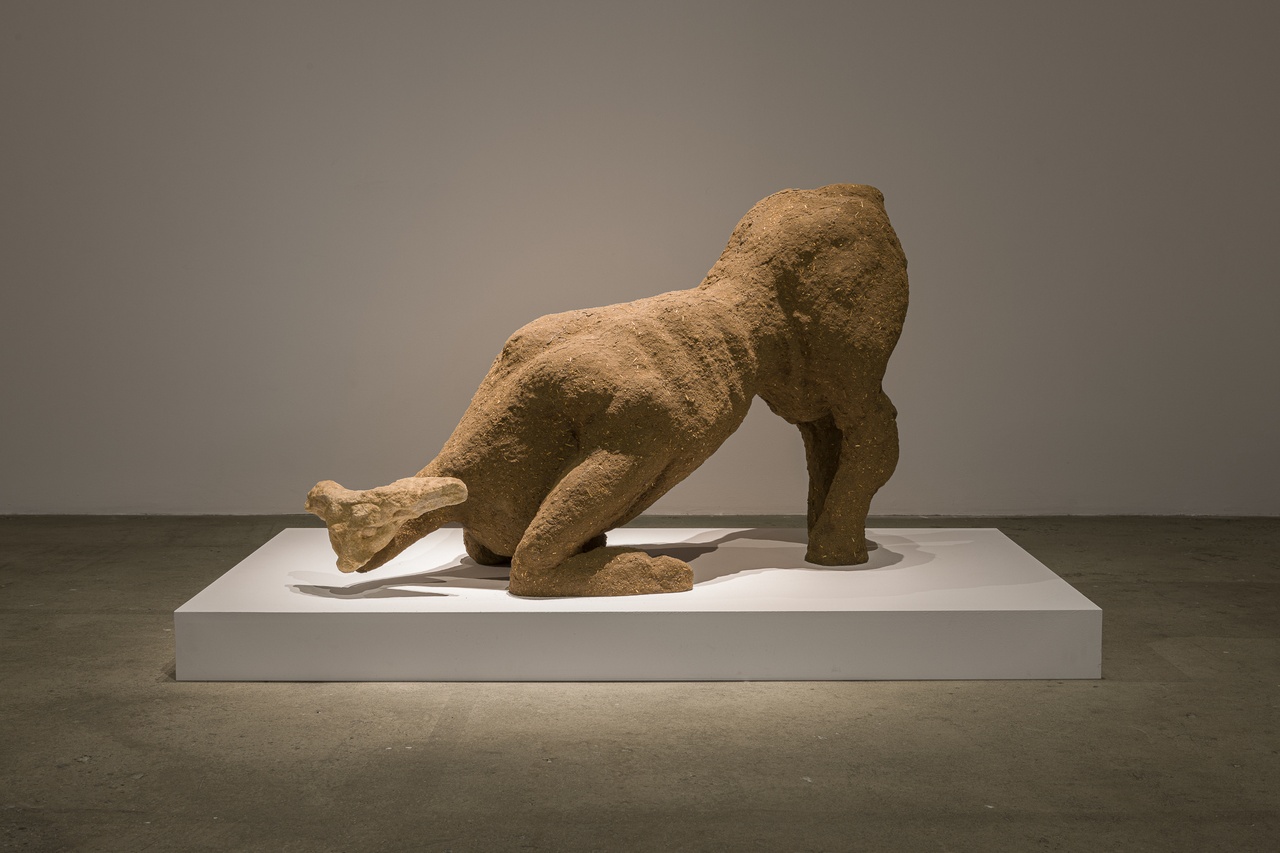

Ali Cherri, “Leaning Figure,” 2023

As though stumbling on a tragedy, the first encounter is unsettling. A gaunt giant leans forward, frozen in bewilderment. Perhaps because of its frontal silhouette, with a framed head and a kilt, apparently made from bricks, it comes across as a roughly fashioned samurai warrior or a Qin dynasty terra cotta soldier. But the ochre figure, made from a fragile material, stands in a rather humble pose, with both palms tenderly held against its chest. Aside from the overall form, clearly molded by hand, there are no distinguishing features. The only exception is a gentle wooden face, a transplanted sarcophagus mask from ancient Egypt.

The tall figure, as suggested by the installation’s title, represents Gilgamesh, the titular character of the eponymous Mesopotamian epic – an odyssey that charts the king of Uruk’s futile pursuit to defeat mortality. The work captures a specific scene, when the protagonist grieves for the death of his companion Enkidu, portrayed in the poem as the archetypal primitive human being, closer to nature than to the cultured Gilgamesh. The distressed figure is positioned to regard a deceased Enkidu, whose body Ali Cherri conceived as a little mound of brown dirt, with erect horns. In the tale, the gods end Enkidu’s life as a punishment for the duo’s transgressions: the slaughtering of the Bull of Heaven and Humbaba, guardian of the Cedar Forest.

Ali Cherri, “The Dreamer,” 2023

Nearby, two smaller works can be seen: a miniature kneeling bull also made of earth, with a stone head from medieval France, and a small standing creature, with truncated legs, a tail, bent arms, and an antelope-like Vili mask from Kongo. Through the doorway to a small back room, the shadow of the last sculpture beckons, drawing viewers to The Dreamer (2023), another short figure with a body of a child whose arms dangle to its feet, and whose face is a rusted cast-iron horned mask from Mali. This figure stands directly on the floor, while Gilgamesh and Enkidu, and the two other sculptures, rest on shallow plinths – suggesting a fragmented stage (the plinths also call to mind museum displays, but the artist’s treatment of the artifacts questions institutional conventions). The works are illuminated theatrically too: occasional flickering lights bring attention back to the death scene, while the smaller figures are generally lit sideways.

In the epic, Enkidu was created out of a pinch of clay; upon his demise, Gilgamesh bemoans his friend’s reduction to the same substance. Each of Cherri’s sculptures is rendered in different tones of mud, with myriad textures. He gives bodies to orphaned archaeological fragments, usually faces or heads – and the invented forms can be more impressive than the antiquities that inspired them, some of which probably never had bodies to begin with. But the bodies are as whimsical, as awkward, and as uncomfortable in the world as the objects he acquires at auctions. They might be Cherri’s attempt to urge viewers to imagine the artifacts differently, to resist the prevalent tendency to value visual spectatorship above all other possible sensory, and even spiritual, modes of engagement. It is an act of creation, but also an act of care for spoils disturbed out of their repose, to be gazed upon without serious reflection on how entire societies have frequently been obliterated in senseless wars – or which simply vanished, leaving us with these memento mori.

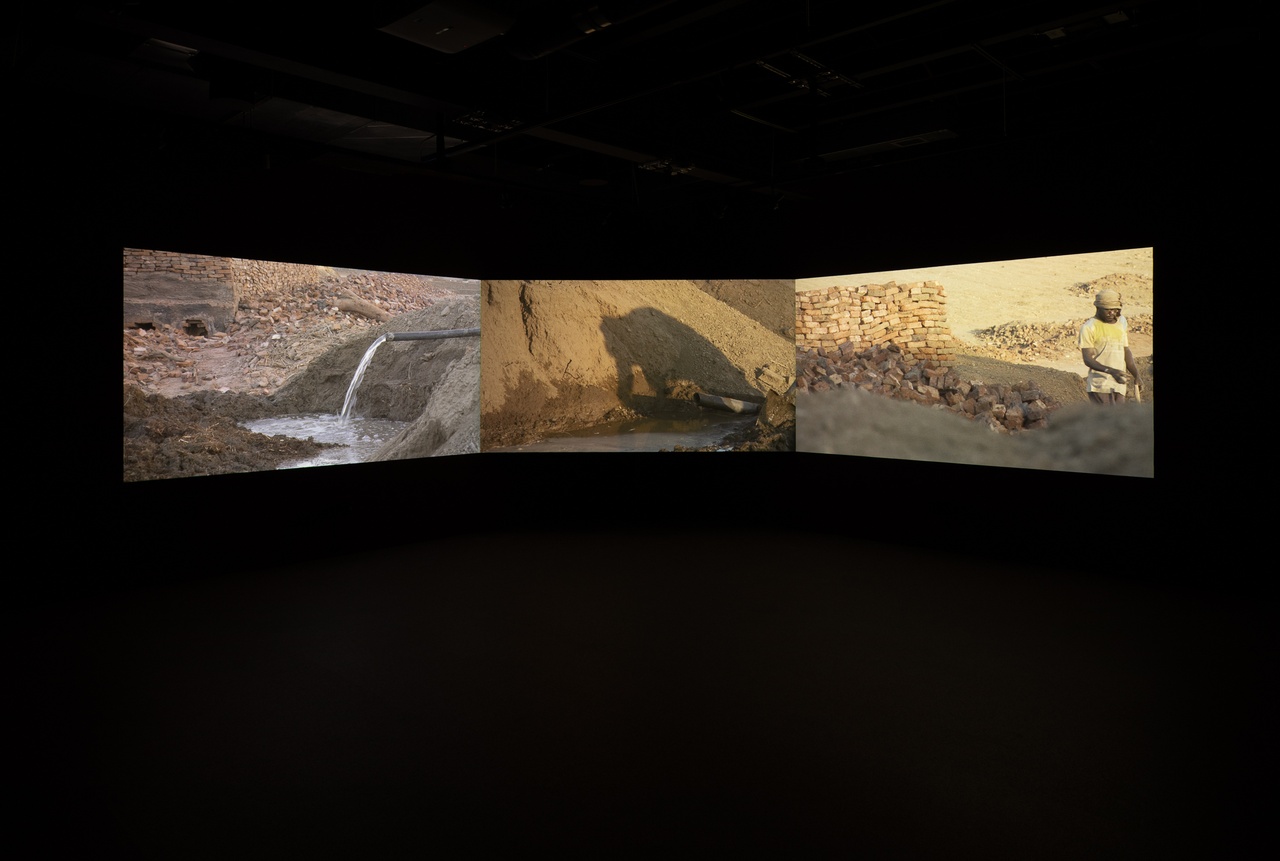

The theme of creation continues on the second floor, where Cherri’s three-channel video Of Men and Gods and Mud (2022) is displayed. In some shots, workers mired in a muddy landscape in northern Sudan shape handmade bricks with such dexterity that one can picture how the sculptures in the level below could have been made, emerging out of the land too. Though it was filmed in the vicinity of the controversial Merowe Dam, the largest in Africa, the work focuses on the brickmakers, and the narrators reflect on how cultures throughout history have repeated the same story, of humanity’s genesis out of mud – ultimately anchoring the commentary in the story of Gilgamesh.

Ali Cherri, “Of Men and Mud,” 2022

The camera pans across a field of drying adobe bricks, which carries an uncanny resemblance to Manhattan’s familiar rectangular grid. But there is a humility to mud, that mixture of earth and water, that seems antithetical to New York. Indeed, it felt perverse to step into this exhibition from the busy streets of the world’s wealthiest city, the de facto capital of US empire, and the paradigmatic metropolis of congestion, excess, and spectacle. It is both fitting and ironic that Cherri’s first American solo exhibition takes place in this city of distractions, so far removed from mud, and from a more intimate bond with soil. This sharp contrast only amplifies the series of dialectical pairings underlying the exhibition, such as the terrestrial and celestial, the human and divine, the archaic and contemporary, the museological and quotidian, the sophisticated and elementary.

The contradictions also conjure – despite the emphasis on the soothing quality of mud in the exhibition’s title – the violence lurking underneath. I am thinking of the mayhem typically involved in extracting resources, and excavating artifacts, from the ground; the savagery of consumer capitalism, commodifying everything into objects with a price tag, including art; the brutality of museums reluctant to acknowledge their colonial roots and voracious appetite for pilfered material culture, or of an art world that determines, with tactfully managed biases, what stories are prioritized, or suppressed; the horrors of displacement, of people and objects alike, uprooted from our native habitats, to be perpetually alienated in foreign lands; and even the barbarity of the epic of Gilgamesh itself, rightly celebrated as the earliest long poem, but often at the expense of tolerating wanton cruelty masquerading as heroism.

Cherri does not explicitly address any of these issues. In fact, neither the video installation, without the aid of external contextualization, nor the sculptural works, devoid of accompanying explanations, reveal much on their own. There was deafening silence in the main space, and arguably in the video as well – the captivating lyricism alone does not make the haunting paradoxes intelligible. It is also not difficult to discern that the artist’s vision is not fully realized: he conceived of the sculptures as one installation, but the floorplan is too small and disjointed to achieve the cohesive dramaturgical presentation he appears to have desired. For me, however, this ambitious exhibition still manages to foreground a crucial aspect of our contemporary reality, namely our fraught connection to land.

“Ali Cherri: Humble and quiet and soothing as mud,” Swiss Insitute, New York, 2023, installation view

I see mud here as the very substance of land, which is critical to underscore, especially at a moment in history when most people barely pay any attention to the ground on which we collectively stand. The numerous crises confronting the world today, such as climate change, economic collapse, political polarization, armed conflicts, and mass migrations, along with the appalling injustices they bring about, often revolve around the right to the land: how land is controlled, how its riches are being used, by whom, and to what ends. Equally, dominion over a territory commonly governs what narratives can be told about the land, and the sanctioned rhetoric may contribute to further exploitation – whereas censored discourses may fuel resistance, and possibly revolution. Governments worldwide are as invested in obscuring these facts as they are in maintaining their grip over inequitable access to land. This is quite evident in Manhattan itself, the traditional territories of the Lenape and Wappinger people, forcibly dislocated by a settler colonialism that eliminated dissent, and disrupted centuries, if not millennia, of indigenous reciprocity with the land.

While the words “land” or “soil” carry nationalistic connotations for some, I prefer to center non-Western perspectives, seeing humans as custodians engaged in a balanced relationship with land, and as extensions of its soil. Creation out of mud may evoke ancient creeds, but it is undeniable that we all return to the land eventually, as though merging with a body we only momentarily escaped. Personally, mud brings back memories of all the mud graves – the coarse contours and textures of which are analogous to Cherri’s sculptures – that I saw growing up in Iraq, in the terrains straddling the rivers Tigris and Euphrates, where the epic of Gilgamesh was recorded on mud tablets. This is also the land where the oldest human civilizations emerged, constructing the first complex cities out of mud, and waging the earliest wars of mass-annihilation.

The thinly-veiled guises of violence in this exhibition are not entirely surprising – psychoanalysts contend that aggression is integral to humanity’s propensity toward self-destruction, its death drive. The exhibition centers death as well, and there are morbid undertones throughout, not just in the Gilgamesh and Enkidu scene – from those inanimate bodies reminiscent of mummified museum displays, to modernity’s greed-driven systems, accelerating an impending doom for which we even have a name, the Anthropocene. Cherri seems to anticipate our end as a species taking the world down with it, while reminding us of our humble, indeed abject, beginnings. His work embodies a primordial message, even if this exhibition’s ruminations can be at times as viscous, and as opaque, as mud itself.

The term ṭīn, or ṭīnā, stands for “mud” in Arabic, but it also refers to someone’s constitution or nature. It is as though Cherri is conveying that the way humanity deals with mud, or land more broadly, says everything there is to know about humanity itself. Insofar as Enkidu symbolizes a nature corrupted – and even decimated – by humanity, I see his death here as an allegory for our dying planet. And Gilgamesh is all of us, humanity in its hubris, contemplating our reckless crimes against the environment, which we have turned to waste. The exhibition’s elegiac musings, therefore, lament our own present tragedy, itself of epic proportions.

“Ali Cherri: Humble and quiet and soothing as mud,” Swiss Institute, New York, September 13, 2023–January 7, 2024.

Amin Alsaden is a curator, educator, and scholar whose work focuses on transnational solidarities and exchanges across cultural boundaries. His research explores the history and theory of modern and contemporary art and architecture globally, with specific expertise in the Arab-Muslim world and its diasporas.

Image credit: Courtesy of the Swiss Institute, New York