Cold Cold Chills Isabelle Graw, David Joselit, Jenny Nachtigall, and Caroline Busta on Jutta Koether`s "Tour de Madame"

Isabelle Graw next to Jutta Koether`s “Isabelle,” 2013, photo by Jakob Lehrecke

Isabelle Graw: 10 Minutes in Heaven

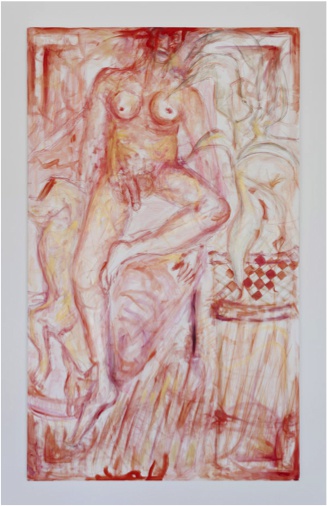

I’ve been asked to give a 10 minute statement about either Jutta´s work or her exhibition at Museum Brandhorst. Considering the time frame and considering the celebratory nature of this event – we are celebrating Jutta´s impressive show, her practice and her sixtieth birthday – I opted for a close reading of one work: a Gouache on paper (2013) titled „Isabelle.“ It´s a piece that I have a special relationship to because it carries my name. Its placement in the show already points to its exceptional status: it hangs high above two other paintings and thus seems to float above everything.

Jutta Koether, “Isabelle,” 2013

„Close reading“ here means that I will try to do justice not only to the material specificity of this work, but also to some of its social (and highly gendered) conditions that inform it, while its symbolism gets modified in turn. I aim to demonstrate that „Isabelle“ is an exemplary work insofar as it sheds light upon Jutta´s painting-procedure, a procedure that both acknoledges and revises a given (oedipal) symbolic order. And the process of titleing a painting is of course part of this painting-procedure.

Let´s start by looking more closely at „Isabelle“: It depicts a sturdy and subtly carnal-looking phallus, which is laid out horizontally, erected to the left. It is painted in a light shade of red: a color that we often find in Jutta´s paintings since the advent of her Poussin-series but the light red here gets permeated by occasional highlights of yellow and blue, which are placed within the painting like set effects.

Jutta Koether, “Hot Rod (after Poussin),” 2009

As far as its outershape is concerned, „Isabelle“ presents itself as a shaped canvas – a by now historical format used by artists like Frank Stella and Ellsworth Kelly in the sixties. These artists expanded the realm of the pictorial with relief-like object paintings. The shape of „Isabelle,“ by contrast, results from what looks like what I would call an „inner necessity“: the depicted phallus with its swollen testicles is presented with so much power, vitality, and reach that looks as though it is striving for even greater space within the picture frame. But while pushing toward a shaped canvas, it is also simulteneously held in check by a painted frame within the picture (we find this structure of a „picture within a picture“ quite often in Jutta´s paintings) This phallus is swelling dynamically toward its borders but it also gets contained and submitted to the laws of Jutta´s painting procedure. You could say that the phallus unfolds its drive on Jutta´s own terms.

But where does „Isabelle“ enter the picture? Why does this painting of an erected phallus carry my name, of all people? Are we to focus on the gap between the picture´s title and what it depicts – a device often used by Jutta and her (mostly male) colleagues from the 1980s that prevented any straigthforward meaning? Or are we to search for correspondences between the symbolic meaning of the phallus and the person whose name this work carries – Isabelle, the phallic woman?

Jutta Koether, “Tate BP Bacon Balthus PdF,” 2015

There is much to be said for the „gap“-theory: Note the tension between the translucent colors of this watery gouache and the phallocratic nature of its sujet. Consider further the history of the gouache: an artform long reserved for female amateurs. So against this backdrop, one could argue that the phallus presents itself here as a symbol of male power that allows for transparency and fragility which in turn relativizes its claims to dominance from within. Phallic power thus can be claimed by a woman, but it also gets modified in the process. We are reminded here of the historical feminist attempts to reclaim the phallus, from Mapplethorpe´s photograph of Louise Bourgeois holding her phallus-object to Linda Benglis famous artforum add.

This modification of phallic power is also reflected in the round male testicles in „Isabelle“. They are lushly painted and modeled in a way that evokes a central element of Jutta´s pictorial language: I am refering to the many round shapes or „knobs“ in her paintings since the 1980s that can morph into faces, breasts or Cézannian apples. Now if we agree that „Isabelle“ also consists of breast-like shapes what follows is that the „natural“ link between „phallus“ and „symbol of male power“ gets disrupted. The breast-like testicles thus raise the possibility of a woman having the phallus. What is more: Since the erected phallus in this picture floats like a partial object, disconnected from a body, it can potentially be claimed by other bodies as well. However, we are equally reminded that women can´t simply leave the oedipal system if they want to succeed in it. Note how the breast-like testicles remain part of an overarching phallus that appears visually quite attractive, vital, and desirable. The phallus here can also be read as an allegory for painting as being historically a mostly male territory that Jutta has often engaged with, as when taking up figures, poses, or compositions from canonic painters like Courbet, Lucian Freud, Poussin, or Francis Bacon. The phallus is clearly a place of abundance, but it is also a symbol of lack – at least according to Lacan. We can therefore perceive „Isabelle“ as an emblem of a sexual drive whose place is always outside of it. Its place is someone else (other) who happens to carry my name. It is the split nature of the drive that gets reenacted by this painting.

Jutta Koether, “Lucian David and Eli,” 2014

But next to these splits or gaps, specific social and biographical realities do enter this picture from 2013 via its title. For instance: I faced radical breaks to do with death and love in 2013 which possibly loosened (or strenghtened?) the grip of the name of the father in my life. This loosening resonates quite literally in „Isabelle´s“ washed out pictorial language. I was also in the midst of writing a book on painting which claimed expertise in a field mostly dominated by men which is something this painting does as well.

The exhibition history of „Isabelle“ is worth mentioning as well: It was first shown in the Alternative Space „Praxes“ in Berlin which points to the importance of friendship, cooperation, and discussion in Jutta´s practice. The provenance of this painting is equally relevant and somewhat inscribed into it: It is owned by Thomas Borgmann, a painting-connaisseur, dealer-collector, and long-time close friend of Jutta´s. It is via the mentioning of his ownership that his impact gets recorded. Social realities thus enter this work, but they also get modified and renegotiated by its painting-procedure. This work inscribes itself within an oedipal symbolic order, admits to its attraction and forces women, like Jutta and Isabelle, to assert their different positions in it while working on its modification.

Jutta Koether, “Pique-Nique (2),” 2017

David Joselit: Fallen Surface

What if the objective of criticism—of statements like the one I am making here--is not to attach a meaning to a work of art, as one places a label on the wall like a small discursive anchor (not unlike the little chains and hardware that lock Monika Baer’s recent monochromes to the gallery’s architecture). There is a reason that object labels are called “tombstones.” The art they accompany is meant to rest in peace. We like our works of art bound by their meanings. Such meanings sit beside the painting in labels meant to render it consumable and accessible--user-friendly--to the audiences that enter museums. It is believed that the public needs to feel comfortable about what they are seeing—they should not be made to confront the terror, uncertainty and precarity, that might be staring down from the walls, or accosting them from the floor. How many among us have seen museum visitors circumnavigate a gallery, first photographing a painting on their cell phone, then its accompanying label (or perhaps the label first!), before moving directly on to the beside it. From this perspective, the perfect act of looking completely evacuates the material artwork—a canvas becomes little more than a pretext for the next Instagram post. It is lost in its appropriation by a mobile phone operated by a mobile viewer. Or think of another function of writing vis-à-vis art. Serious scholarly research on art—which is being progressively attenuated in the American academy—is put in the service of marketing. Art historians now populate the research departments of major New York galleries. They write sophisticated art-historical briefs in the service of selling paintings. Their job is to give no more and no less than is necessary to move a luxury commodity. The prestige of knowledge (or at least the idea of it) carries over onto the prestige of art as a commodity. Or perhaps, we might wonder if the prestige of art--as something glamorously sheathed in the lamé evening gown of capital--lends some auxiliary legitimacy to art history. In any event, assigning a meaning is essential to making a sale. Placed within the two framing conditions I have mentioned—the tombstone label and the salesman’s brief—painting’s materiality is dispossessed, either as information, or as capital—which under current conditions are more or less the same thing. You can’t have capital without information, or information without capital, which is perhaps the reason why art, which is itself a highly prestigious precipitate of information and capital, has had such luck catching the eye of oligarchs.

Jutta Koether, “Universal Wealth,” 1987

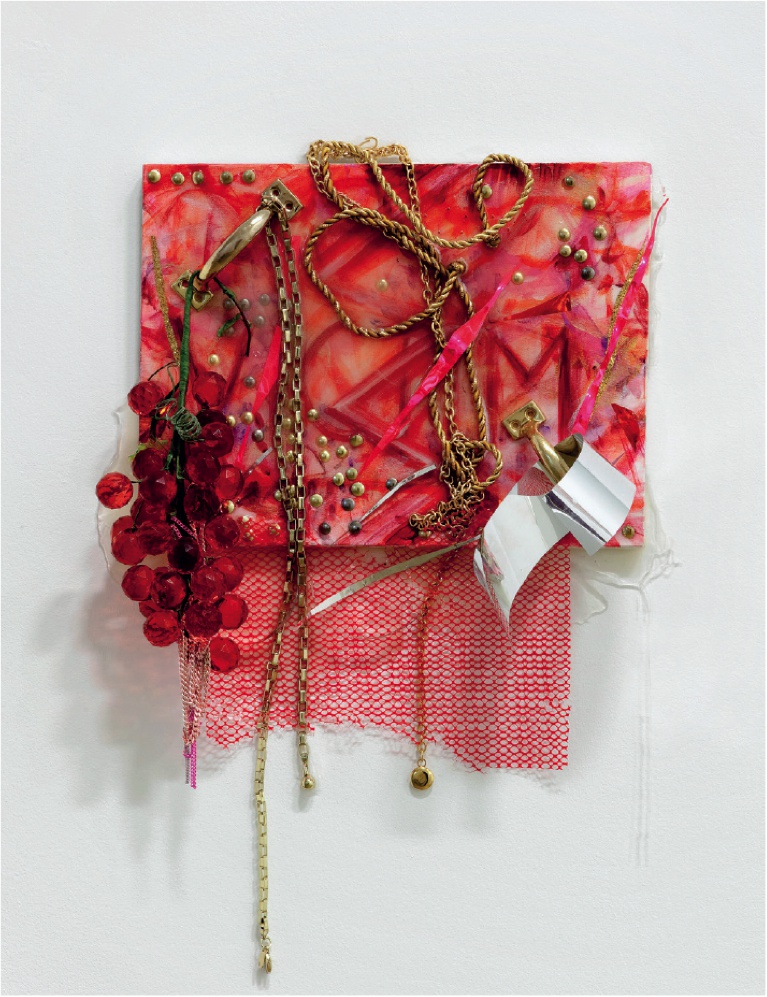

I would rather not, then, occupy my limited space here displaying my professional training by earnestly attaching a meaning to the work of Jutta Koether. But if I don’t, what remains to be said that the paintings have not already enunciated? Perhaps the how of criticism matters more than the what. How can one speak of painting in a way that does not anchor it to the museum wall or the auction block with one’s well intentioned assignments of meaning? In this regard, it is worth taking a hint from the title of Koether’s show: “Tour de Madame.” The bilingual double entendre of tour—tower in French and voyage in English—suggests a constitutive duality. On the one hand, the tower is absolutely locked in place, while going on tour is the epitome of mobility. Let’s consider how paintings go on the road—how they might rattle their chains. In a work like V of 2009, Koether sets surface free—a hanging bunch of red plastic grapes, some tangled chains, a bit of fat silver ribbon detach themselves from a slippery ground of liquid glass. Chains, tacks, and handles gesture toward the painting’s shackles but these are certainly inoperative. Gravity seems to have taken hold of them—everything seems to be slipping off under its force. The image invites grasping and yet it is fallen. Fallen, but not dead—not ready for a tombstone label. What might it mean to think of a surface that has slipped from our grip—that is “fallen” (with all its moral and physical connotations). Is Madame perhaps a fallen woman? This fallen surface, caught in the act of falling is very different from the other modernist metaphors we have on hand for thinking of surface--the drip and the flatbed. To me V looks like a gorgeous pound of flesh that has been lifted out by its handles. When the surface becomes a bedazzled slab of carnage--the living dead--a tombstone is not enough to immobilize it.

Jutta Koether, “V,” 2009

Koether has made an unbound surface, but one that does not display the interiority we often associate with abstract painting, as when we claim that Jackson Pollock is representing his unconscious with propulsive vectors of paint. Koether’s surface is in motion, but not dispossessed. It is self-possessed. I want to pause to reflect on the paradox of its behavior for a moment. The surface is in motion, it feels carnal and animate (this is one of the many effects of Koether’s attraction to the color red). And yet it does not invite us to find a meaning inside of it. The detachment of the surface—its mobility—enables a kind of animism without interiority--without there being a meaning behind the work for people like me to discover and for others to monetize. Perhaps this is why I’m so fascinated by Universal Wealth of 1987. Here, interiority is doubly banished from the grids of little paintings that line the transparent acrylic display case in their gridded formation. Each of these ordinary modest images is furnished with a text on its verso. Is this text a meaning that the artist has conveniently laminated to the painting, as though the tombstone label and the paint surface are fused into a chimera? No! These are not meanings, they are merely other textual images on other surfaces, which are alphabetic rather than mimetic. What’s more—these 86 paintings have arranged themselves around a void. They share an interior—a literal interiority of the vitrine—BUT IT IS EMPTY. Why, we might wonder, is this work called Universal Wealth. I can only speculate, but to me the swarming of these image-text dyads, each freed, and yet each caught in a whirlpool around a void gives us a definition of capital. These paintings are held together—but also held apart—by gravity. By the gravity of the spectacle upon which postindustrial capital depends. They are still-lives that won’t keep still. It is said that Isaac Newton discovered gravity by observing an apple fall. Jutta Koether rediscovered the apple (and gravity) in fallen surfaces.

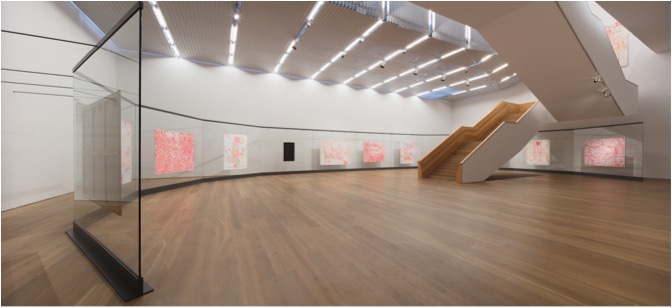

But what happens when surfaces go on tour? They enter into space, and they make of painting something very different from a commodity. It is a kind of articulate spatial punctuation which is explicit in Koether’s insertion of a second transparent glass architecture into the Brandhorst’s lower galleries. It is the Tour de Madame in both senses of the word.

“Jutta Koether: Tour de Madame,” Museum Brandhorst, Munich, 2018, installation view

Jenny Nachtigall: Notes on Painterly Loops

Arguably Jutta Koether’s practice has always been driven by a desirous relation to painting. At least this is what I’m going to proceed from in the next ten minutes. Although Koether has frequently drawn on a classical painterly canon, performing her mastery through it, the canon continuously figured as a means to an end – a means to a “Tour de Madame”. Tour de Madame, like so much in Koether’s practice, is a name, a concept, a proposition on painting as much as it is a proposition of painting: an act of painting, a gesture of intensification itself.

In other words, Tour de Madame as retrospective blurs the boundary between the territory of presenting painterly propositions in a museum and the territory of production, the studio. Because Koether’s understanding of form does not know aesthetic hierarchies, for her the museum context becomes one form – one bit of data or information – amongst many that is employed in her territory of production. She uses this information – as much as Cézanne’s Apples, Lucien Freud’s nude, the figure of the genius or the position of the female painter amongst others– as a means for her own ends.

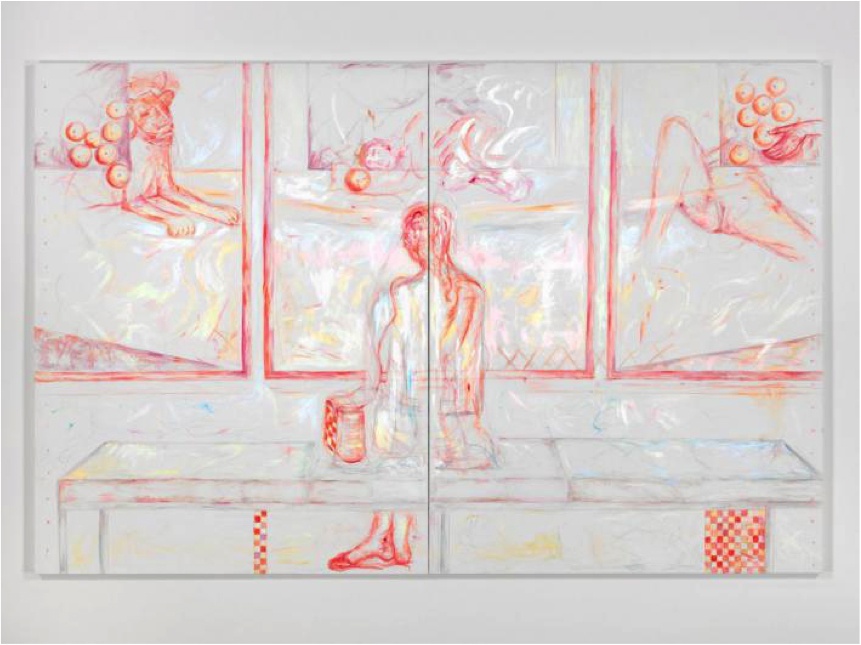

Jutta Koether, “Tour de Madame 1,” 2018

What I mean by that is that Koether’s painting could be understood as a mode of information processing. By nominalizing art historical knowledge and the forms in which it materializes – for instance the museum – as information to be processed, she creates her own kind of software (that is defined by an extreme porosity towards para-artistic inputs such as music, or text). Processed through this software art historical information gains another life: a new life in painting.

And the central piece of the exhibition, the Tour de Madame Cycle is exemplary for just that: for both painting as medium of processing art historical data and as software to generate Koether’s own info. So I’m going to focus on this work in my input. In this cycle Koether reformats anew motifs, movement and methods of her painterly position of the last 35 years. She, in other words, treats herself, or rather her painterly position, as art historical information – an information that needs processing as much as the info-unit that is the Brandhorst Museum (both are among the components that define the format of the retrospective).

Hence, the semi-circular glass pane that supports twelve new paintings mirrors the layout of Cy Twombly’s monumental Lepanto-Cycle (2001) in the museum’s top floor – aka Tour de Monsieur. When I first entered the museum’s basement the Tour de Madame Cycle as a gesture and proposition made me think of a comment by Lynda Benglis (an artist whose work is admittedly not necessarily related in practice but perhaps in attitude to Koether’s). Benglis comment is: “It’s all about territory…how big”? Benglis talked about her interest in media like video and about how it enabled gestures freed from material and spatial constraints: the gesture could be as large as possible. Her most notorious gesture of claiming a territory was of course the widely circulated 1974 Artforum ad in which, Benglis, naked, donned a supersized double-dildo (and as you know this was a case of too much information feeding back into the system: two of Artforum’s main editors left the magazine). Tour de Madame is a big gesture too, but is also in a different way about territory, about the material and discursive space of painting, and about how Koether occupies it. Unlike the Lepanto Cycle both the show as a whole and its central piece do not unfold as a (visual) narration but in loops: loops of different forms, gestures and methods across canvases, evading full closure.

The show becomes actually more loop-like or labyrinthine the more time you spend in it, the more you trace the circulation and metamorphosis of different forms and gestures from one room or one painting to the next – going back and forth and in circles. Kathy Acker once described the centre of André Masson’s Acéphale drawing – the colon – as a labyrinthine territory subject to change or fortune or chaos in which the measured self of reason and critical judgment loses its firm ground – is thrown back onto its body. For Acker the colon is an organ/machine/medium of a bodily kind of processing. One should add, though, that the colon could be read in discursive register alike: a colon in the grammatical sense is a punctuation mark that signals a proposition, an explanation. For me the Tour de Madame Cycle is both a kind of bodily processing – a processing of painterly bodies and of Koether’s bodies of painting – and a painterly proposition (a labyrinthine body-grammar-medium perhaps?).

What I mean by this short-circuit of the bodily and the discursive is for instance the fact that the processing of painterly bodies, the excessive formatting and re-formatting of Koether’s own painterly information– a re-appropriation of her own painterly position, if you will – is itself embedded in a kind of grammatical structure: the cycle’s first and last paintings function as a bracket (or indeed, as a loop).

Jutta Koether, “Tour de Madame 2,” 2018

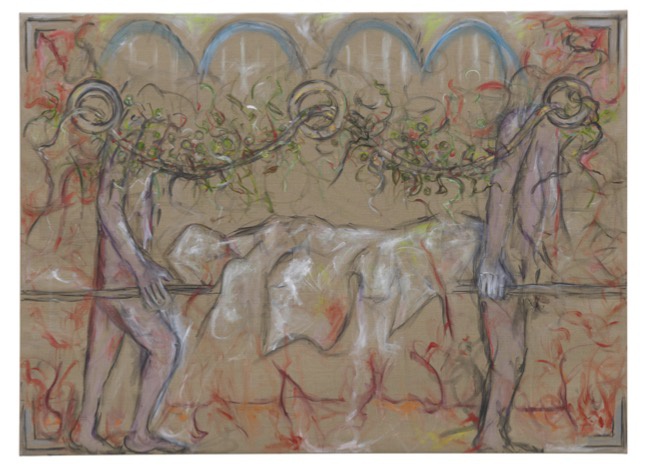

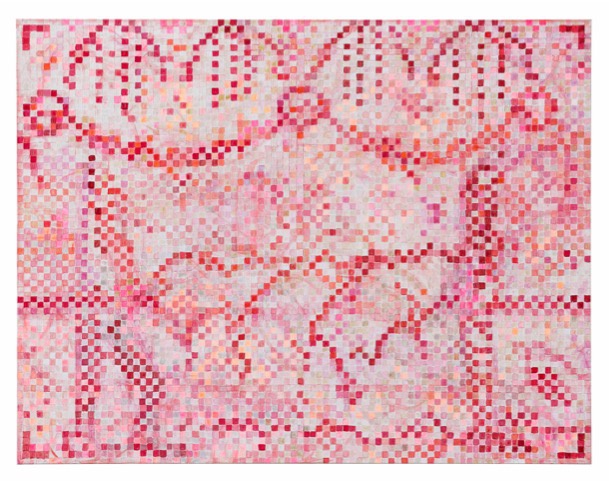

In the first painting of the cycle two rough sketch-like acéphalic figures carry a stretcher on which rests an amorphous bodily shape covered in a white cloth. Everything appears loose and unfinished on the laid bare canvas. The horizontal line of the stretcher extends beyond the frame (traversing the other images of the series). The image actually threatens to unravel were it not for the corners to assert a frame. And the laid bare canvas appears to devour the figures: headless already, arms and legs dissolve into lines and gestures. The figures merge into the ground – the canvas becomes the body, the figures just a mark/sign – a quote to be more precise taken from Nicolas Poussin’s Landscape with the Funeral of Phocion (1648) (another version of Koether’s self-portraits of painting perhaps: a self-portrait of an artificial kind of body that is more dead than death – and thus oddly alive). In the last painting the motif is re-formatted in Koether’s bruised grid shapes of different hues of red and pink and yellow highlights that here appear like pixels in a bad computer graphic. This loop from the first to the last image, to be sure, does no describe a progressive or regressive movement from dead painters (or dead painting) to lively pixels – or the other way around.

Although the set-up of the cycle itself caters to a digitally calibrated mode of perception and the format through which we consume images – the glass pane as a screen with a lot of open windows – the question of anachronism (that of painterly production in the face of the digital) is arguably not what’s at stake in Tour de Madame. Because the question of painterly progress is not – Koether’s Tour de Madame instead progresses painting, mobilizes it, make it move (through her own body but also ours). So, if I initially talked about Koether’s painting as a mode of information processing, I’d like to add, that one could also think of it as a kind of metabolism. Like the colon though – a figure of the bodily and the discursive – it is not either or but both at the same time.

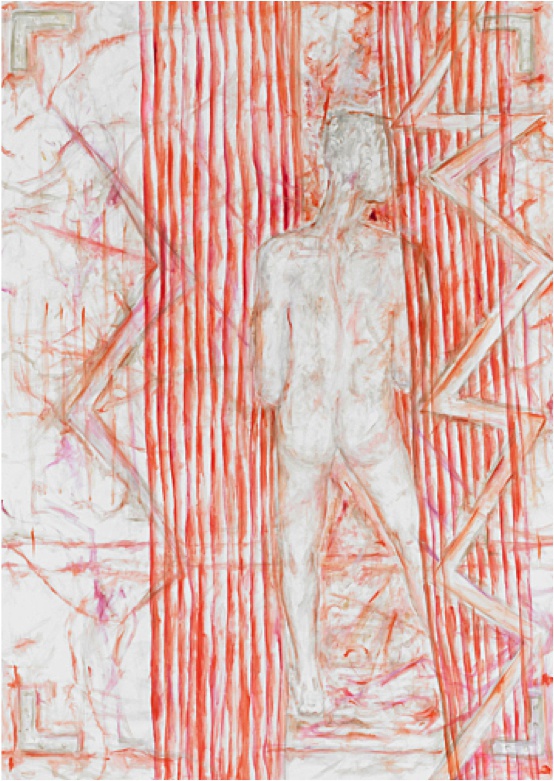

Jutta Koether, “Berliner Schlüssel (extra 1),” 2011

Caroline Busta

We can talk about what painting does within a recognized painting discourse, but I'm interested in thinking about Jutta Koether's paintings and her practice over all, as they relate to our larger mediascape. To be clear, I'm not interested in how Koether's production functions within a contemporary mass media scope; how many likes it gets, etc. But how the terms of her work read in the context of the attention economy; or—in a time when Koether's work is as likely to be viewed IRL in a physical space as it is to be encountered on screen.

This is to say, how do the terms of her work actually register to the screen-oriented viewer, the viewer whose instinct upon arriving at "Tour de Madame" is to immediately re-mediate what they see? Well, for those of cradling your phones right now, my feeling is that Koether's work may have special resonance for you... Why? Because in a strong sense, these paintings are not so much objects but in their own right, screens. And the way in which they ask one to engage is fundamentally social.

But what do I mean by this?

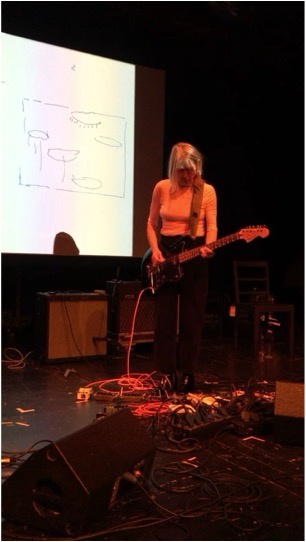

For Koether, painting is a kind of live portal — or as Michael Sanchez writes in his essay for the exhibition's catalogue, a space of "transmission and reception" through which she makes "contact" with her network and the wider world. From Koether's "Inside Job," (where viewers would schedule appointments with her one-on-one, at her apartment to see her painting giving her live feedback) /// to her numerous collaborations with other artists such as, for example, Kim Gordon as you saw last night, or John Miller, Tony Conrad, Steven Parrino, as well as collective artist avatars where her own identity/authorship contributes to a collective body: for instance Reena Spaulings or past projects such as Lee Williams, Grand Openings.

And then there are the late afternoon / early evening "viewing sessions" she will sometimes arrange so that one can experience her paintings in the changing light.

Jutta Koether, “Berliner Schlüssel #1,” 2010

In all of these instances, there is a sense that painting, for Koether is an active interface, one that she uses to access certain spaces and networks but also one that has protected her from the often alienating or unsustainable conditions of cultural production today. In a way, it's as if Koether has, with painting as medium, made her own social platform—the canvas (and its transitive regions) a space to be filled with her network's content. In this scenario, Koether is a receiver of information, of data, of codes. But unlike big stack social media (Instagram, Facebook, etc), the filter, here, is human; it's her.

Koether can be seen as a master gatekeeper, a door-woman filtering who gets in and what can enter her stream, and who and what cannot. Koether enforces a local of her own design. Enforces an inside. In a time of total transparency, total exposure, Koether creates a "club in the shadows."

To gain entrance, one must not only have the key but must also know how to operate it.

The object alone is not enough. It is always, for Koether, object plus gesture. To take the Berliner Schlüssel (the Berlin Key), which is a recurring motif— or could we even call it a 'meme'?— in Koether's work, the action of unlocking requires both the special object and the social knowledge of how to use it. In this way— and we see this also with, say, the synth elements Koether uses in her music collaborations—technology is never separate and inorganic, but a shared interface between artist's mind, human body, and physical world.

The Berliner Schüssel as a meme in Koether's work, is particularly interesting for another reason though: as the [door-unlocking] gif illustrated, it requires the user to pass the key through the door, and to then relock the door behind them as they extract the key. Thresholds are guarded in Koether's sphere. This mechanism makes sense in the context of 90s Cologne of course, where the intimacy of that scene created a kind of nuclear discursive pressure. But it makes just as much if not more sense now, in a time of forced transparency — or worse: such extreme alienation that one voluntarily surrenders TMI, the most intimate information to an anonymous mass... and they -- we! -- tend to do this compulsively out of inner need.

This is to say that capitalism, within a neoliberal dispositif, mines interiority, leaving subjects flat, uncomplicated, and all the better as a surface of transmission. A quote from Byung-Chul Han, "Psychopolitics" 2017: "Digital control society makes intensive use of freedom. [...] Secrets, foreignness and otherness represent impediments to unbounded communication. In the name of transparency, they are to be eliminated. Communication goes faster when it is smoothed out — that is, when thresholds, walls, and gaps are removed. This also means stripping people of interiority, which blocks and slows down communication." Koether's selective reception and transmission, her insistence on an inside and an outside, and painting as a kind of screen too but one that creates a rupture, a gap, within a world of digital screens, feels deeply relevant as a statement that physical painting can make right now.

There are two more things I want to briefly say here:

1. Is how, given the above, Koether's paintings not only act as interface, but also as a kind of proxy or corporate shell. Indeed her own paintings tend to function as aggregators. And you can see here a construction that Koether uses not infrequently: where a painted subject is looking at other paintings. And further to this, we repeatedly see in Koether's work not so much painted self-portraits of Koether but Koether as a painting. But the aggregation effect is also present in her collectively created works. Through an approach to painting as proxy, Koether maintains her artistic position (does not lose herself) even when entering into artistic collaborations. For example, take this work from 2004 (you're seeing both sides here), which marks the beginning of Reena Spaulings the artist. Invited to participate in a group show at PS1 in New York, Koether negotiated with the curator, Bob Nickas, to allow "Reena Spaulings" (at the time an unknown artist) to take her slot. I'm not sure if Nickas was aware, but viewers would not have know that Reena was in fact a collective, and that this work, organized by Koether, would contain works by several artists -- including contributions by John Kelsey, Josephine Pryde, Josh Smith, and Emily Sundblad, none of whom were officially in the show. As such, this piece functioned both as a platform for Koether's community and also as a vehicle, a platform on wheels, a Trojan Horse for smuggling her community through the institution's own gate system.

Kim Gordon performing at Cold Chills, Museum Brandhorst, Munich, 2018

Under the sign of 'painting' Koether could leverage her own cultural standing to open up a space for collective activity, presenting an object whose sign value was incoherent, a sign value that could not be easily communicated; that was full of secrets and otherness. In this work, Koether used the sing of "painting" as a shell— a shell for generating a shadow space where the "outside" could exist "inside" (the institution, in this case) without that "inside" stripping away personal interiority.

OK and last point -- and here I'm offering a collective voice as it was actually something that my partner observed in Koether's work: the way that she approaches the canvas seems to have somehow anticipated the way many people actually do use social media now: identifying and repeating certain gestures that we find to be memetic and valuable, making images about -- and for -- our friends, making images that stand in for our own presence, mediagenic images that are meant to take up space in the public sphere, to become beacons for identifying our tribe out in the world wide web, even as we...meanwhile, slip out and back down into the club in the shadows, back into the private sphere.

Isabelle Graw teaches art history and art theory at the Hochschule für bildende Künste in Frankfurt /M. (Städelschule). Her most recent publication is entitled: “The Love of Painting: Genealogy of a Success Medium” (Berlin 2017).

David Joselit is Distinguished Professor of Art History at The Graduate Center, CUNY. His most recent book is After Art (Princeton University Press, 2017).

Jenny Nachtigall lives in Berlin and is a lecturer in the Department of Philosophy and Aesthetic Theory at the Academy of Fine Arts, Munich.

Caroline Busta is an author und publisher of https://newmodels.io.