IN PRAISE OF SHADOWS Diana d’Arenberg on Raha Raissnia at Empty Gallery, Hong Kong

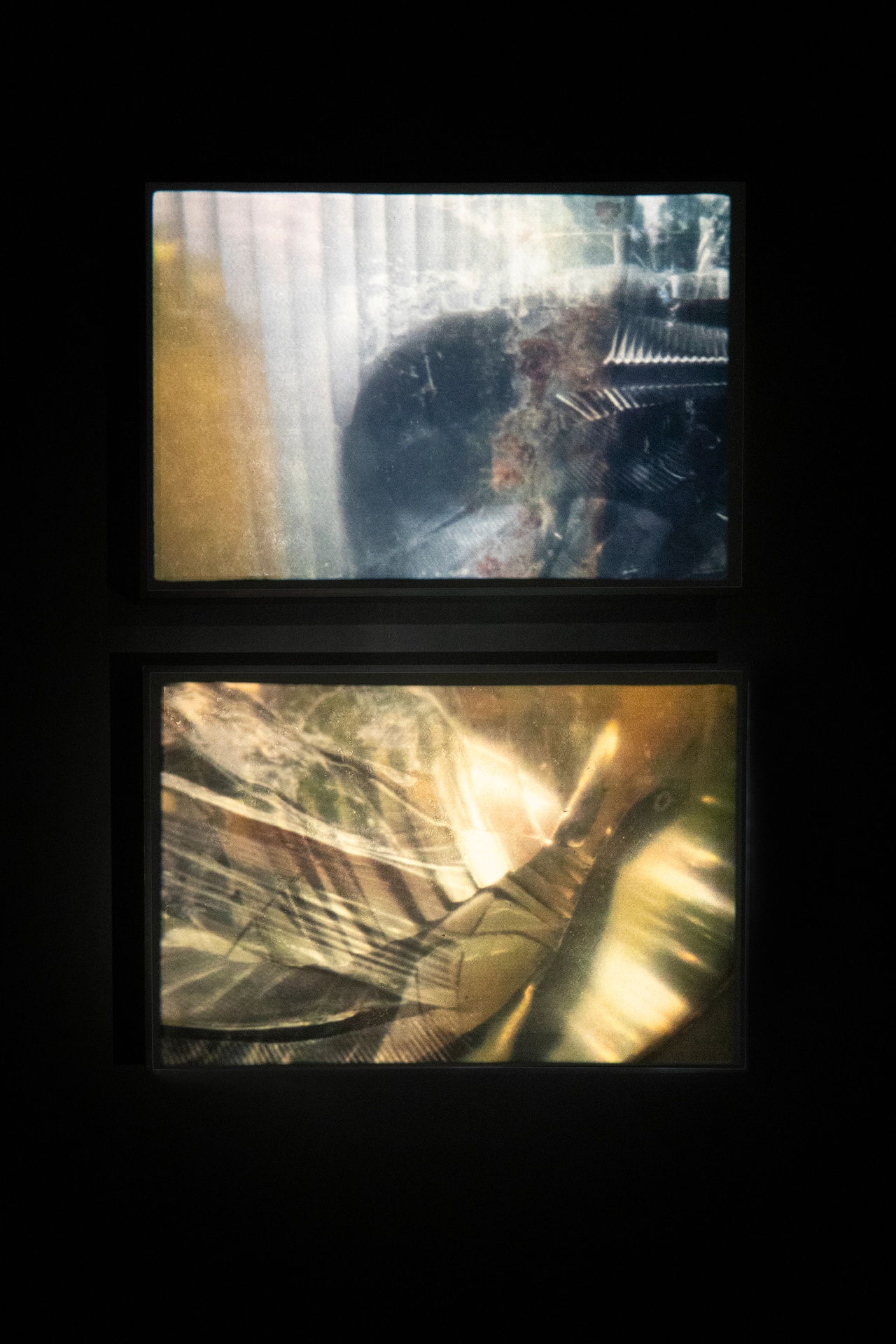

“Raha Raissnia: Nour,” Empty Gallery, Hong Kong, 2022-23, installation view

Iranian-born New York–based artist Raha Raissnia’s first solo exhibition in East Asia, staged at Empty Gallery in Hong Kong, sees visitors step into a theatrical pitch-black gallery space in a high-rise industrial building. Eyes and mind are deprived of visual clutter and distraction, left to focus instead on the softly lit artworks that take center stage in the gallery (the only illuminated objects in the entire space). Titled “نور ” – transliterated as Nour, meaning “light” in Farsi – the exhibition is as much an exploration of darkness as it is about light, and its potential to illuminate and create shadows. Leaving behind the visual white noise and auditory stimuli of the world outside, visitors enter a world of analogue and alchemy.

The exhibition consists of twelve works from 2022 and 2019, encompassing 35mm and 16mm film and installation, graphite and charcoal drawings on paper, and oil and acrylic paintings on canvas, all executed in moody dark tones. The chiaroscuro present in the works creates a tension between light and shadow, the visible and invisible, denseness and transparency. Images dissolve into and emerge out of light and shadow.

The centerpiece and titular work of the show, Nour (2022), a 16mm black-and-white film projected through a large semitransparent scrim cube suspended from the ceiling, greets visitors upon entry to the gallery space, the clicking sound of the film projector cutting through the silence. The work is both a two-dimensional film and a three-dimensional sculpture as the projection beams through space onto and through the floating cube and against the black gallery wall behind it. Raissnia’s interest in avant-garde filmmaking led her to an internship at Anthology Film Archives in New York for several years in the mid 1990s, and it carries through into her painting, drawing and film works today, all of which overlap and inform one another. The film projection – like the rest of her work in the exhibition – is created through a densely layered handmade process of cutting and collage, manipulating and layering preexisting photographic material. Time, space, and narrative are splintered as Raissnia samples, reassembles, loops, superimposes, and cuts up film drawn from a personal archive of images – some found, other photographs taken by the artist. The process is transformational, resulting in a hypnotic, kinetic visual language, a moving abstract painting indebted to silent cinema and experimental film. Bursting with flickering light and shadow in a continuous three-minute loop – with no discernible beginning or end – Nour taps into the subconscious, allowing the imagination to take over. Using a process that calls to mind William S. Burroughs’s cut-ups, where text and image fragments are pieced together in order to expand language and human consciousness, Raissnia’s film projections and paintings reveal a disrupted, blurred, and fragmented reality, suffused with a Tarkovskian nostalgia.

“Raha Raissnia: Nour,” Empty Gallery, Hong Kong, 2022-23, installation view

A child when the 1978–79 revolution broke out in Iran, Raissnia cites expeditions with her father to photograph protests against the Shah as an influence on her work. The artist returned to Tehran as an adult to photograph places she had once visited and has on occasion used her father’s negatives in her work. The personal extends into the universal as the artist reprocesses memory, history, narratives, and perception, and calls into question the veracity of photography.

Photography “passes for incontrovertible proof that a given thing happened,” Susan Sontag writes in her seminal collection of essays On Photography (1977). But in Raissnia’s work, photography doesn’t confirm reality or experience – rather, it makes it more ambiguous. Instead of revealing any particular truth, her images obfuscate. The manipulation, distortion, and layering of photographed images subverts the intention of a photograph. This ambiguity suggests how photography is employed as a utilitarian tool – in politics, culture, and in the creation of our own narratives – where the image can be reframed, edited, recontextualized. The images she uses may correspond to a particular time and place, but by manipulating them, Raissnia engages with questions over the nature of memory, truth, and representation, as well as film’s or a photograph’s ability to accurately document subjects or to objectively represent historical or private moments.

Photography here is not used for the purpose of bearing witness, but rather to tap into an inner world. In Nour, geometric and architectural shapes and apparitions in striking contrast of light and shadow are blurred, cropped, and scratched. There is something nostalgic and comforting about getting lost in the flickering projection. It calls to mind the enveloping hushed darkness of an old movie theatre with the clicking of the projector. At the same time, the lines of steel and concrete cutting through abstract compositions recall the futuristic urban dystopia of Fritz Lang’s German expressionist sci-fi film Metropolis (1927). They disappear and reappear, fluttering across the cube and the wall like fragments from a dream or memory, as though the artist is attempting to capture the ephemeral. Memories too can be smudged, their edges and details blurred, or manipulated by others.

Displayed beneath spotlights in an adjacent room, are seven large, monochrome paintings and three graphite, charcoal, and ink works on paper. All are densely layered and composed of photographic image transfers that are drawn from the artist’s personal archive. A topography of texture reveals itself across the shimmering metallic and densely black-painted surface as Raissnia draws and paints across the canvas, adding layers, smudging paint, scraping it off. Her bifurcated graphite compositions – smaller-scale studies for larger paintings – lack the luminosity and depth of her paintings but are similarly drawn, redrawn, erased, layered, scratched, scribbled, with indentation and erasure marks visible on the paper.

“Raha Raissnia: Nour,” Empty Gallery, Hong Kong, 2022-23, installation view

While Raissnia brings together different practices and media, her works intersect in the use of photography as source imagery, and in an architectonic thread that runs through the exhibition. But the paintings and drawings also draw on the cinematic, with multiple spatial and temporal planes crammed onto a single surface. Past, present, and future merge, and boundaries between mediums bleed into one another. Geometric and architectural fragments, spectral figures and forms materialize and disintegrate into darkness and stillness, occupying a liminal space between abstraction and figuration.

There is something magical yet unsettling about Raissnia’s oeuvre – the artist as a creator not just of works but of worlds. Fragments of cities and landscapes – conjuring the images of war and ruin we are bombarded with daily in the news cycle, as well as archaeological sites that have succumbed to time and decay – appear in an atmospheric collage in the compositions. They float untethered, joining other shapes in a geometric maze, or dissolve into amorphous masses of black or reflective paint. From chaos, a geometric order emerges. Scraps of a decorative semicircular arch can be made out in the visual collage of the golden-hued Tympanum (2022), while Doric (2022) offers foggy glimpses of overlapping vertical and horizontal columns and staircases, tenebrous and concealed under striated brushstrokes. Mycenaean Dream (2022) – a painting which fuses details from a preexisting smaller drawing and image transfer of the same name (2019) – features a figure, taken from a photograph of a stone sculpture of Zeus, arms outstretched, floating in the center of the canvas panel, surrounded by a circuit board of interconnecting patterns in a clash of the ancient, modern, and futuristic.

In the confusing collage landscapes of shapes and forms, it is almost impossible to make sense of exactly what we are looking at. The process of erasure, redrawing, collaging, and layering that is central to Raissnia’s practice interferes with our ability to decode the works and derive a concrete, linear meaning from them. But cities and landscapes are palimpsests of history and narratives, with the past erased, manipulated, and rewritten through war, violence, and various political regimes. Raissnia’s work rightly challenges notions of narrative and identity as static and allows for a multiplicity of perceptions. The act of looking is active as we excavate through the layers of paint, graphite, and film, immersed in a world that forges the imagination from light and shadow, destruction and reconstruction.

“Raha Raissnia: نور ” at Empty Gallery, Hong Kong, December 10, 2022–February 18, 2023.

Diana d’Arenberg is a Hong Kong–based art writer and musician with rock band The Strixx. She has worked with international galleries, art fairs, and biennials, as well as international publications, including Harper’s Bazaar, South China Morning Post (Hong Kong), LEAP (China), Vogue, The Art Newspaper, Ocula, and Christie’s.

Image credit: Courtesy of Empty Gallery, photos Michael Yu