Andrew Stefan Weiner on Cameron Rowland at Artists Space, New York Disgorgements: Art, Incompletion, and the Carceral State

The U.S. system of mass incarceration is so sprawling, massive, and seemingly irreparable that social scientists often refer to their own struggles to represent it as a totality, rendering it in terms of a negative sublime. One might expect artists to refrain from even trying to depict the carceral state, or do to so in familiar humanistic terms. Cameron Rowland’s recent exhibition “91020000” broke with these expectations by opening with a conceptual work bearing the seemingly benign title “Partnership” (all works 2016). To execute the piece, Rowland initiated an agreement between the long-running New York venue Artists Space and a division of the New York State Department of Corrections called Corcraft, which employs prisoners at well below minimum wage in the production of various goods, ranging from roadwork equipment to office furniture, with the stipulation that these products can only be sold to other state-run or not-for-profit entities.

Rowland’s “Partnership” essentially consisted of a license – its number referenced by the show’s title – given to Artists Space (as an eligible non-profit) to purchase Corcraft goods. While in one regard this maneuver positioned Artist Space as an accomplice of the prison-industrial complex, it simultaneously registered the gallery as the state would an inmate, with a government-issued numerical ID. Through the ambiguities of “partnership” – a term all too familiar to post-Fordist discourse – Rowland complexly aligned the institutions of art with those of the carceral state, and also with a neoliberal ideology in which various types of coercion are often cast as “collaboration.”

Cameron Rowland, "Attica Series Desk," 2016. [2]

Cameron Rowland, "Attica Series Desk," 2016. [2]

Economical, precise, and highly ambitious, this opening work concisely framed the rest of Rowland’s exhibition, which engaged an urgent set of highly over-determined sociopolitical problems. Viewers were presented with a spare, deliberate layout in which a small group of carefully chosen objects and documents aimed to connect aspects of mass incarceration with the long-term aftereffects of slavery, including the phenomenon of “re-enslavement” within convict lease programs during Reconstruction and after. [3] Such a venture was aptly timed, coming at a moment when criminal justice reform is finally appearing on the U.S. national agenda, partly due to the efforts of Black Lives Matter activists, and when Democratic primary campaigns have been punctuated by the renewal of debates over reparations. Given that prison populations have slowly begun to decline after decades of unchecked increases, present conditions would appear to hold out some prospect of change, however modest.

Part of Rowland’s intervention consisted of research, in the form of a distributed text that cited scholars, statistics, and case law to gauge the current dynamics of the U.S. prison system, outlining the dimensions of a crisis that extends far beyond the estimated 2.2 million people currently in U.S. prisons and jails to include the millions more who are subject to probation, parole, immigrant detention, and other forms of state control. This is not to mention the radial impact of these individuals’ lives, whether through broken families and depopulated communities, or the creation of a large class of disenfranchised, marginalized ex-convicts who are sentenced to a kind of “civil death.” [4] Other related issues have to do with the structural contradictions of mass incarceration, particularly those concerning its connections to neoliberal hegemony and to various modalities of racism.

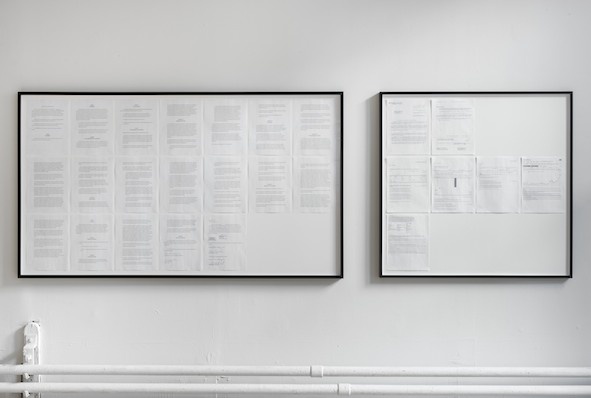

"Cameron Rowland: 91020000," Artists Space, New York, 2016, installation view

"Cameron Rowland: 91020000," Artists Space, New York, 2016, installation view

In contrast to activist artists who focus on effecting concrete policy changes through legally operative art (e.g., Laurie Jo Reynolds’s “Tamms Year Ten” project, which successfully helped to shutter Illinois’s state supermax prison), Rowland’s recent work develops a comparatively abstract, research-based approach that seeks to both analyze and alter the frames through which mass incarceration is perceived. Crucially, these frames are not only narrative or conceptual, but aesthetic. One key implication of this stance is that before we can reform or abolish the carceral state, we have to understand the ways it distorts its own perceptibility and intelligibility. Any effective intervention requires that we grasp the way these sensate biases determine public debate by predisposing a given public to certain kinds of action (or inaction).

It was with such aims that “91020000” sought to make the secretive economy of prison labor more intelligible. Rowland took advantage of the Corcraft partnership to create a series of sculptural installations from objects that the state effectively commissions for itself. Among the products-turned-artworks were the self-descriptive pieces “Attica Series Desk” and “Leveler (Extension) Rings for Manhole Openings,” along with “New York State Unified Court System,” a set of empty benches arranged as if in anticipation of some forthcoming verdict. Refraining from any conspicuous mediation of these objects, Rowland pre-emptively eliminated the opposition between the forced labor of the prisoner and the ostensibly free or redemptive labor of the artist. Freed from the demand to signify as technically refined art, the objects were marked by an emptiness that allowed them to assume a spectral character, conjuring coerced labor and the haunting of the liberal democratic state by its carceral double. Rowland further constrained the expected function of these works by keeping them off the market. Rather, in an arrangement that both blocks speculation and cancels the artist’s potential profit, the pieces for this show were made available only for lease at cost, with this price directly indexing the exploitation of prisoners’ labor, along with the savings this incurs for the state.

The remaining pieces in the show extended the prison analogy to address the persistence of the slave economy in American society after slavery’s abolition, focusing on select practices of the insurance industry. In a suite of three works, each titled “Insurance,” Rowland installed a number of large lashing bars of the kind that are used to secure cargo on container ships. He also obtained certificates from Lloyd’s Register, the still-operative British organization established in 1760 to help underwriters assess the risk of insuring ocean voyages, including many that facilitated slave trade. Whereas these works do not directly censure Lloyd’s or demonstrate concrete links between past and present, Rowland’s more trenchant piece “Disgorgement” does, making explicit that the American insurer Aetna (founded a decade before U.S. law forbade the ownership of slaves) issued insurance policies for human property. This practice – which expressly excluded death or damage inflicted by the slave owner – generated capital by objectifying human life, handling it as goods. As Rowland shows with Aetna, a robust present-day company, the residual value of slavery still exists within the fabric of corporate America, a point that is seldom made within mainstream discussion. Moreover, the implications of this stance resonate within the institution of art, as in the case of recent research demonstrating a correlation between slavery and the 18th-century discourse of aesthetics. [5]

Cameron Rowland, "Disgorgement" (detail), 2016 [6]

Cameron Rowland, "Disgorgement" (detail), 2016 [6]

To make “Disgorgement,” Rowland worked with Artists Space to purchase 90 shares of Aetna stock, placing the assets into a non-profit trust. He then stipulated that this account will exist indefinitely, terminating only in the event that federal slavery reparations are paid – in which case the shares will be sold and the profits paid into the federal fund. Although on first inspection the piece seems to manifest the clinical dispassion of much institutional critique, its effects are considerably more ambivalent. As noted in the work’s detailed description, Congressional support for reparations is currently non-existent. The likely fate of the piece is thus not to effect the remediation it calls for, but rather to exist in a state of perpetual unfulfillment. Incapable of realizing its potential as a promesse de bonheur, art figures here instead as an incomplete restitution.

Such a compromised horizon indicates a decisive tension in the aesthetico-political orientation of Rowland’s exhibition. Generally speaking, “91020000” adopts a position that is largely consistent with recent progressive consensus, seeming to support reparations and prison reform while denouncing the sort of racialized criminal justice that has earned the name “new Jim Crow.” [7] Yet even as this narrative has a potent affective charge, it courts objections to which it is largely unable to respond. One thinks here of the ongoing debate regarding reparations, in which some have argued that such a policy would homogenize class differences among African-Americans while failing to call for a more radical coalition-based challenge to neoliberalism. [8] Other counter-arguments might turn on the fact that Latinos, poor whites, and women make up an increasingly large part of U.S. prison populations; or that prison laborers are less representative of the carceral state than unemployed prisoners, who are literally captive consumers for various enterprises. [9] Rowland’s work is strongest where it begins to register these problems at the level of its form, whether in the multivalent complexity of “Disgorgement” or in the contradictory status of the Corcraft appropriations, which make few demands aesthetically yet many conceptually, remaining at once inert and highly charged. In such instances, it is possible to grasp how research, art, and politics can complement, antagonize, and transform each other, and how such encounters might form the basis of future interventions.

"Cameron Rowland: 91020000," Artists Space, New York, January 17 - March 13, 2016.

Andrew Stefan Weiner is Assistant Professor of Art Theory and Criticism at the New York University.

Notes

| [1] | "Cameron Rowland: 91020000," Artists Space, New York, 2016, installation view. This photo and all following: Adam Reich, courtesy of the artist and Essex Street. |

| [2] | Full caption as stipulated by artist: "Attica Series Desk, 2016. Steel, powder coating, laminated particleboard, distributed by Corcraft 60 × 71.5 × 28.75 inches. Rental at Cost. The Attica Series Desk is manufactured by prisoners in Attica Correctional Facility. Prisoners seized control of the D-Yard in Attica from September 9th to 13th 1971. Following the inmates’ immediate demands for amnesty, the first in their list of practical proposals was to extend the enforcement of “the New York State minimum wage law to prison industries.” Inmates working in New York State prisons are currently paid $0.10 to $1.14 an hour. Inmates in Attica produce furniture for government offices throughout the state. This component of government administration depends on inmate labor. |

| [3] | In an essay framing the exhibition, Rowland cites Douglas Blackmon’s study “Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II” (New York, NY: Anchor Books, 2009). |

| [4] | For a critical synopsis of these issues, see Marie Gottschalk, “Caught: The Prison State and the Lockdown of American Politics” (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014), 1-23. |

| [5] | See Simon Gikandi, “Slavery and the Culture of Taste “(Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014). |

| [6] | Full caption as stipulated by artist: "Disgorgement," 2016. Reparations Purpose Trust, Aetna Shares. Aetna, amongst other insurance companies, issued slave insurance policies, which combined property and life insurance. These policies were taken out by slave masters on the lives of slaves, and provided partial payments for damage to the slave and full payment for the death of the slave. Death or damage inflicted by the master could not be claimed. The profits incurred by these policies are still intact within Aetna. In 1989 Congressman John Conyers of Michigan first introduced Congressional Bill H.R. 40, which would "Establish the Commission to Study Reparation Proposals for African Americans to examine slavery and discrimination in the colonies and the United States from 1619 to the present and recommend appropriate remedies." The bill would convene a research commission, that would, among other responsibilities, make a recommendation as to whether a formal apology for slavery is owed, whether reparations are owed, what form reparations would then take and who would receive them. Conyers has reintroduced the bill to every session of congress since then. This bill acquired 48 cosponsors in 1999-2000. Currently it has no cosponsors. In 2000 the state of California passed the bill SB 2199, which required all insurance companies conducting business in the state of California to publish documentation of slave insurance policies that they or their parent companies had issued previously. In 2002 a lawyer named Deadria Farmer-Paellmann filed the first corporate reparations class-action lawsuit seeking disgorgement from 17 contemporary financial institutions including Aetna, Inc., which had profited from slavery. Farmer-Paellmann pursued property law claims on the basis that these institutions had been enriched unjustly by slaves who were neither compensated nor agreed to be uncompensated. Farmer-Paellman called for these profits and gains to be disgorged from these institutions to descendants of slaves. The Reparations Purpose Trust forms a conditionality between the time of deferral and continued corporate growth. The general purpose of this trust is “to acquire and administer shares in Aetna, Inc. and to hold such shares until the effective date of any official action by any branch of the United States government to make financial reparations for slavery, including but not limited to the enactment and subsequent adoption of any recommendations pursuant to H.R. 40 – Commission to Study Reparation Proposals for African-Americans Act.” As a purpose trust registered in the state of Delaware this trust can last indefinitely and has no named beneficiaries. The initial holdings of Reparations Purpose Trust consists of 90 Aetna shares. In the event that federal financial reparations are paid, the trust will terminate and its shares will be liquidated and granted to the federal agency charged with distributions as a corporate addendum to these payments. The grantor of the Reparations Purpose Trust is Artists Space, its trustee is Michael M. Gordon, and its enforcer is Cameron Rowland. The Reparations Purpose Trust gains tax-exemption from its grantor’s nonprofit status. |

| [7] | I refer here to Michelle Alexander’s recent study “The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness” (New York, NY: The New Press, 2012). |

| [8] | See Cedric Johnson, “An Open Letter to Ta-Nehisi Coates and the Liberals Who Love Him,” published online at https://www.jacobinmag.com/2016/02/ta-nehisi-coates-case-for-reparations-bernie-sanders-racism/ |

| [9] | See James Forman Jr., “Racial Critiques of Mass Incarceration: Beyond the New Jim Crow,” NYU Law Review, April 2012; and Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2007). |