„Do Things Dream of Geometric Sheep?" Bruno Macaes on Absalon at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin

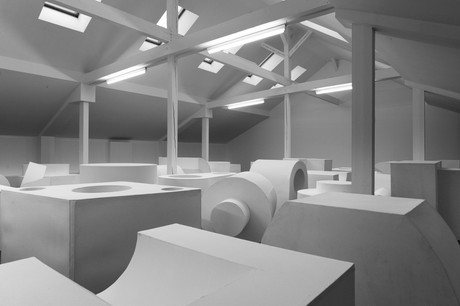

Absalon, Installationview, 2010, Foto: Uwe Walter, 2010

A famous economist once noted that in a modern economy no individual is important enough for his or her death to affect the stock market. One could make the same point still more forcefully. Do we understand our society better by investigating the life cycle of people or the life cycle of things? The life cycle of things seems more important, does it not? We get to determine what people do in relation to things and what they do. At this point one could protest that only human beings have secrets, a life of the mind, a view from within. But is this really true? Imagine a labyrinth of geometric volumes, arranged more or less randomly on the floor, each the result of different combinations of a much larger number of forms and shapes: Parallelepipeds, open and closed cylinders, cones, spheres. There is a sense of moving through a logical space of possibility, without knowing in advance which form will be realized in the volume in front of us. Looking becomes a dance of curiosity. One begins to entertain the fantastic thought that these pieces are slowly showing us all that they know already. Artists like Donald Judd have given us artworks which are deliberate attempts to shake our assumptions, developed over many encounters with sculptural and architectural shapes. The first impression we have of an object will be later denied from a different view of the same object, revealing that the initial assumption was an illusion, produced by the accumulated knowledge of previous visual experience. But one could also build artworks that explore the mystery of unrevealed shapes, that place the viewer before the interrogation of what is there and cannot yet be seen.

Absalon, „Disposition", 1990, Foto: Uwe Walter, 2010

The questions one asks when facing these works are questions suggested by the shapes of each particular piece, and then answered by these shapes. It may be a question whether a through hole in a geometric volume has an opening at one or both of its ends. The way to do this is to follow the contour of the volume to one end and then the other. The movement of consciousness between question and answer is strictly identical with this contour. One could perhaps imagine that an easy question takes the shape of short cylinder and a difficult conundrum would appear as an impossibly long shape. The interesting point, of course, is that these alternatives have no evident human meaning or importance and yet one is irresistibly led to consider them and to look for the answer. They do not show us those country estates of classical painting which made Balzac wonder, who lives there, what do those people look like, are they happy? Our curiosity has been brought down to the level of the physical object, perhaps even absorbed by the object.

The description above refers to an installation work created by the Israeli artist Absalon in 1990, part of the magnificent retrospective of his work being shown at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art. The curator Susanne Pfeffer wisely reserved this piece for the top floor of the exhibition in the attic of the building, where it feels like the culmination of a carefully pursued project. Absalon was just beginning to explore the possibility of building cells or containers for human habitation and the main question, when thinking about his work, is to determine the final meaning of this project. “Disposition” (1990) is already a container, a cover or case, albeit not one that we might use in order to humanize a commodity lost in the capitalist economy. On the contrary, Absalon wants to give human beings a cover, a container, a wrapper, on which, as in the case of a commodity, one may fully specify what is to be found inside. I feel that one could reconstruct the pieces being shown by recording the movements of the viewers walking around in the exhibition. The simplest of forms acquire such conviction or compulsion that the viewer feels all his movements have been choreographed in advance and in this respect it is possible to think of all his work as a habitation for the human mind, a collection of perceptual and practical machines telling us what to see, how to act, what to do. Value and meaning may be produced in the mind of the beholder, but what happens when we face works which are capable of directing human consciousness? I want to say that these works invert the normal relation between man and things. They do not exist within human consciousness as perceptual images. Rather, human consciousness may be said to be contained within the works. Here is why they have to be so stringent, so abstract and inevitably white or colorless, the image of a physical, objective world, before the human eye breaks down the colors in the light spectrum. They exist not in order to be seen, but in order to make us see. We know what this means from the experience of cinema, where the objects of perception have been determined in advance by a chemical imprint and its mechanical reproduction. In Disposition this relation is much more complex, since the objects we see are spread out on the floor and hence responsible for guiding our movements and determining what will be seen next.

Absalon, ”Cellule No.5", 1991, Foto: dreusch.loman, 2010

In „Cellule" (1991), created a year later, Absalon offers us a most remarkable variation on the same idea. The five cells are slightly larger than human scale and the interiors may suggest the possibility of being inhabited. More important, however, is the way he has made these interiors visible. He uses neon tubes to lit them, but in their structure they are closed, fully solid volumes, replicating on the outside the same geometric shapes we find in the interior furnishings. What allows the viewer to look inside is an opening obtained by carefully excising one piece from the wall, a square or a half circle, which is then left on the floor next to the cell. The effect is to turn the opening into something like an eye, creating the space for vision and rendering our own eyes powerless by comparison. These are perhaps less sculptures than an ambiguous form of installation, where the space of the viewer is also the internal space of the artwork. All the emphasis is placed on this internal space rather than the space of the room in which they stand. The effect is disquieting because Absalon has in fact created a material equivalent of the human eye: one could close the piece and make the visible world disappear as surely as by closing our own eyes. We always see what has been made visible. There we stand, before these immense, artificial eyes, with the growing feeling that what we are doing is neither original nor important, that human vision is the faint echo of a more fundamental process. The viewer, even if he has paid for his admission ticket, is after all the superstructure.

Absalon, ”Cellule No.5", 1991, Foto: dreusch.loman, 2010

To see is always an imitation of the more fundamental act of making visible, something happening in the material world of objects and not the world of human consciousness. By 1993, at the end of a tragically short life, Absalon had produced an extraordinarily coherent body of work. This exhibition makes that very clear. On our way down from the games of Disposition we are able to follow the repetition in motifs and ideas which seemingly had always preoccupied the artist. In the portable homes exhibited in the main hall there is perhaps a moral theory in disguise ”(Cellule) Prototypes“, 1992). Absalon spent some time in Villa Lipchitz, built by Le Corbusier, and the influence is surely visible in these minimal cells. Before everything else, they are a program for life and maybe even an attempt to make life scientific, to raise the chaotic elements of human life to the status of physical laws or, as he once put it, to make life more exact, more precise. Which way and what concept of life do they offer? While the cells have been built so as to dictate his actions and behavior while living in them, this discipline was no longer social or political. Absalon would have escaped into a different world: the very fact that this discipline is given by a physical object means that to a considerable degree one can understand, elaborate and act on it as a thing in itself, without direct reference to other human beings and certainly without human intervention. But, of course, these objects were produced by a human being for his own use. They are a law he gives himself, a law as inflexible as the walls of the cells. Habitation stand for bathos, the absorption of human consciousness by the objects it creates. Thus, the fact that the bookcase in each of these houses cannot hold more then fifteen books at a time will have a direct and immediate influence on the way its occupant lives and maybe even the way he thinks. Does he have to take up a limited number of ideas at a time, just as the bookcase can only hold a limited number of volumes? Perhaps. Be that as it may, the goal is less the modernist rationalization of space or the functional flight from ornament than the inflexible discipline of the object.

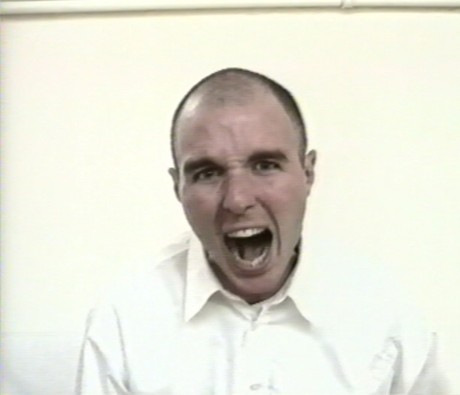

Absalon, „Bruits", 1993, Filmstill, courtesy Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie

In this inflexibility there is of course an escape from other forms of discipline, those imposed by cultural, social, and political forces, and therefore a way of making it possible to be as free within society as one would be outside it. You must change your life, Absalon liked to repeat. He certainly had in mind something more radical than a new choice or new values. In fact, he always insisted that his work was meant to resist any tendency towards utopia. He wanted to close the gap between thought and reality. “I am attempting to create an infallible system, which in a certain sense is a total prison.” _1 Each of these homes was meant to develop and realize different aesthetic and practical possibilities. By multiplying these possibilities, Absalon was indulging his taste for experimentation and adventure. At bottom, however, we always find the unmistakable appeal to a higher power, a power beyond human authority. Let us find necessity in things, not in the caprices of men.

“Absalon”, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, November 28, 2010 – March 6, 2011

Notes:

1_ Absalon, CREDAC, Ivry-sur-Seine (France), 1990