"The Dream of the Realists" Isabelle Graw on “Courbet. A Dream of Modern Art” at Kunsthalle Schirn, Frankfurt/Main.

Gustave Courbet, "Portrait de l´artiste, dit L´homme blessé", 1844?1854

The Courbet show in Frankfurt seeks to draw a different picture of Courbet, one going “beyond realism”. The exhibition’s curator, renowned art scholar Klaus Herding, states that this perhaps most radical 19th-century political painter, who went to prison for endorsing the destruction of the Vendôme Column, was “one of the greatest dreamers in history”. At first sight, this proposition made and explicated by means of a carefully choreographed exhibition itinerary is quite informative. For it seems to be a laudable approach to place emphasis not – as is so often done – on the socially engaged Courbet, the painter who not only depicted social misery in paintings such as the now lost “The Stone Breakers” (1849), but also made it vividly experienceable as a form of physical ‘domestication’. But doesn’t this proposition of a dreamy Courbet, despite the insights it gives, ultimately tone down his project to a kind of individual fantasy? When Courbet showed his solidarity with the Paris Commune in 1870, while at the same time holding the official post of an art commissioner, wasn’t more at stake than just dreaming of different conditions? Nonetheless, Herding has rightly discerned a hitherto hardly acknowledged “somnambulistic sensualism” in Courbet’s paintings, which he impressively underscores by referring to the numerous portraits of either sleeping or in other ways absorbed figures. However, particularly in regard to the motif of sleep, it must be added that the persons we see dozing in Courbet’s pictures are always women, for example, in “Sleeping Woman” (1849), “The Sleeping Embroiderer” (1853) or “The Young Girls on the Banks of the Seine (Summer)” (1856).

Gustave Courbet, "Les Demoiselles des bords de la Seine, été", 1856?1857

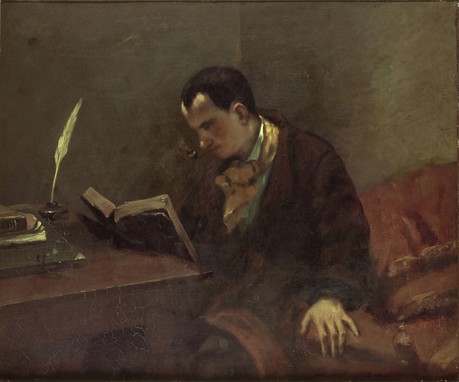

In my view, Courbet was less intent on depicting variations of being lost in dreams than on dealing with the consequences of the division of labour along gender lines. The sleeping women he portrayed, all members of the bourgeoisie, were simply excluded from the sphere of labour at the time. They could allow themselves the idleness he captured in these paintings, but they were condemned to inactivity. The numerous portraits of befriended male cultural producers, similarly contemplating, staring into space or immersed in reading (from the art critic Champfleury to the famous picture of reading Baudelaire), must also be interpreted less as signs of Courbet’s interest in idleness or introspection than as persons representing cognitive work. Courbet appears to have grasped the immaterial character of this intellectual work – consisting foremost in contemplation – avant la lettre, as it were. The fact that this immaterial labour created value is stressed by the specific materiality of his paintings – the putty-knife painting technique that Courbet applied made his pictures look crude in the eyes of his contemporaries, and even today, they partially appear as if they were daubed.

Gustave Courbet, "Portrait de Charles Baudelaire", 1848

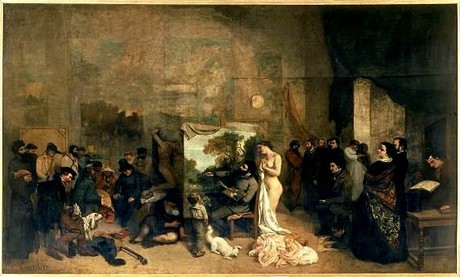

Hence, the problem with the show in Frankfurt is not that it shifts the emphasis away from the realistic to the “sur-realistic” (Herding) Courbet. Instead, the problem is that it posits this perspective as an absolute, as if Coubet had been an escapist dreamer, thus pushing his reference to society to the background. The realism that Courbet had advocated in his manifesto from 1855, by the way, had little in common with the concept of realism that has experienced a strange renaissance in today’s art world – most recently at the last BerlinBiennale, for instance. When in today’s art world talk is of realism, it usually has to do with complaining about art’s alleged distance to reality that needs to be overcome by once and for all indulging in a reality grasped as “authentic”. Apart from the fact that the fine arts have in truth long arrived at the centre of the prevailing conditions, especially since the present-day artist now embodies the prototype of the much-invoked entrepreneurial self, what Courbet’s understanding of realism instead aimed at was to reflect on structures of social inequality, including his own position as an artist within these structures. In his well-known studio painting (“The Painter’s Studio”, 1855), Courbet drew himself as the perhaps most questionable figure of the “allegorie réelle” (Courbet), exploiting misery for his own creativity and living off of rich patrons.

Gustave Courbet, "L´Atelier du peintre, allégorie réelle déterminant une phase de sept années de ma vie artistique", 1855

Yet what always remains open with Courbet is whether he grotesquely exaggerated the given conditions, which were also the conditions under which he lived, or whether he documented them in an empathetic way. Particularly the poses he struck in the long series of self-portraits should therefore not be taken too directly. It is true that he often painted himself with half-closed eyes. However, this come-to-bed look, which can be found in “Self-Portrait with Pipe” (1849), for example, stands less for the introspection of the depicted figure than for the ambivalence one encounters in all of Courbet’s works. In his self-portraits – especially apparent in the extremely theatrical “The Wounded Man” (1844-1854) – Courbet strikes typical romantic poses, but he claims them for himself only to the extent to which he exaggerates and ridicules them. This self-ironic moment in Courbet is lost in Herding’s insistence on introspection and immersion. This also applies to the interpretation of “The Meeting, or Bonjour, Monsieur Courbet” (1854), a picture that is fortunately included in the Frankfurt show. It was said to have been popularly, and tellingly, called “Fortune Saluting the Genius” at the time. Here, Courbet rendered the meeting between his patron, Alfred Bruyas, his servant and himself as if it had taken place on a brightly lit stage, in the form of an experimental set-up. In contrast to his pictures held in earth and brown tones, the painting is bathed in bright light and appears almost graphically painted. The artist meets his patron as a free, energetic and independent vagabond, while the patron (and his servant) appear comparatively humble and seem to have tipped their hats first. The power of this painting lies in its potential to reflect the market.

Gustave Courbet, "La Rencontre ou Bonjour, Monsieur Coiurbet", 1854

Courbet addresses the free artist’s new independence of the private collector, especially since it is a commissioned work, so as to assert symbolic independence based on this dependency. The painting has little to do with a “daydream in the state of being wide-awake” (Herding), for the actually existing conditions of dependency are quite clearly inscribed in it. Even in the case of Courbet’s famous “A Burial at Ornans” (1850), which confronted the Parisian citizens with their carefully suppressed provincial background, Herding, in his catalogue text, wants to prove that the depicted actors – the residents of the small town of Ornans – are somnambular. They do appear somewhat rigid and absent, yet the somnambular impression of the actors alone would never have caused such a stir. According to T.J. Clark, the painting caused an affront for the reason that it blurred the border between bourgeois and paysan, because it was both grotesque and serious, and because it displayed the mode of painting typical of Courbet, which was deemed crude. Moreover, Clark showed the way in which Courbet actually calculated to be reputed as a bad painter, when, in “The Peasants of Flagey Returning from the Fair” (1850-55), he positioned an ugly pig in the middle of the picture, sniffing around in muddy earth tones. Against this background, the dreamy atmosphere of his paintings proves to be a minor aspect, yet one which, in Frankfurt, has been declared a main characteristic. Such a shift in focus comes at the cost of more complex interpretations that do better justice to what is at stake in Courbet’s art. Yet it must be acknowledged as an achievement of this show that it brings to the fore a hitherto disregarded side of Courbet’s art, and it does so in the form of a programmatic theme exhibition, which one rarely encounters nowadays.

(Translation: Karl Hofmann)

First published on January 14, 2011 in "Tageszeitung"

“Courbet. A Dream of Modern Art” at Kunsthalle Schirn, Frankfurt/Main. October 15 - January 30, 2011