THE GRAY AREAS Ewa Borysiewicz on Aleksandra Waliszewska at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw

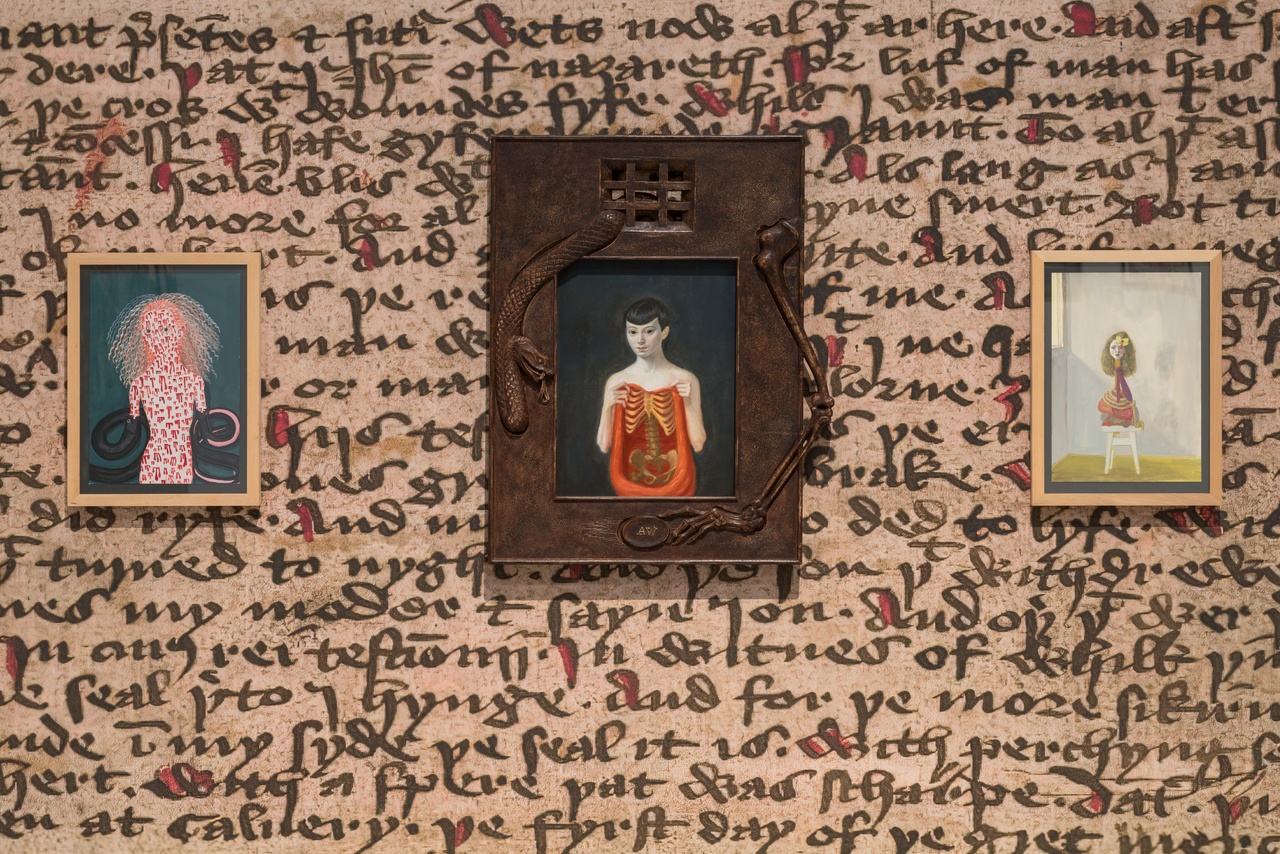

“The Dark Arts: Aleksandra Waliszewska and Symbolism from the East and North,” Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, 2022, installation view

The first image we encounter in the catalogue accompanying “The Dark Arts: Aleksandra Waliszewska and Symbolism from the East and North,” Waliszewska’s monographic show at Warsaw’s Museum of Modern Art, is a snapshot of the artist’s studio. It is crammed with art books: tomes on medieval masters of illumination, monographs of Renaissance portrait artists, volumes on Romantic landscape painting, as well as books full of cryptic symbolist and surreal imagery. “I think I tend to absorb art rather than analyze it in a discursive way. […] I don’t like reading about art, I just enjoy looking at it. I think it’s an issue of today’s artists, that they tend to read more about art than experience it visually,” [1] Waliszewska says. Her ocular appetite knows no bounds: it allows the artist to fuse diverse imagery, independently of genre, chronology, or register. With her attentive gaze, Waliszewska takes in this mass of representation and weaves it into a captivating, intricate iconographic system of her own. But by purely concentrating on the visual aspect of her sources, she often risks dismissing the context and ideological fabric of the works she admires so much.

Waliszewska’s focus on visuality and her reluctance to provide explanations of her work – expressed in the few interviews she’s given – is reflected in the curatorial method applied by Alison M. Gingeras and Natalia Sielewicz. In constructing the show, the curators have given priority to association and visual correspondence, rather than to a historical, linear order. In consequence, “The Dark Arts” works both as a survey providing a visual genealogy of a particular creative vision, and as an exercise in speculative art history. From the many references that Waliszewska utilizes, Gingeras and Sielewicz chose Symbolism from Eastern and Northern Europe as the starting point for the show. Certainly, the Symbolist path is one of many that can be followed to investigate and contextualize Waliszewska’s oeuvre, and the decision by the curators results in a reorientation of the usual, Western-centric narration (concentrated on the late 19th-century developments in Belgium and France) covering this movement in the arts, and a chance to present its lesser known varieties.

“The Dark Arts: Aleksandra Waliszewska and Symbolism from the East and North,” Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, 2022, installation view

Owing to her masterful use of beauty and the macabre, the artist enjoys a mass following on social media. As mentioned, the show’s focus point is visuality and its fluid logic, thus the text throughout the show is limited to the bare minimum (Waliszewska herself does not title her works). The artist’s works, as well as the historical loans, do not follow a rigid temporal order and their presentation in the exhibition space tries to mirror the absorption and filtering method that can describe Waliszewska’s work. Overall, the exhibition itself does not offer the viewer straightforward guidance or a single narrative to follow. For example, rather than a chronological arrangement of the artworks, running from 1997 to 2022, the presentation has been structured into five interlocking sections, displayed in the museum’s vast exhibition pavilion. Each focuses on one thread of Waliszewska’s dense web of references and delivers a proposal for the interpretation of her work.

The chapters offer some unexpected encounters. Take, for instance, “Mortality, Disease & Mourning,” juxtaposing Waliszewska’s portrait of a lamenting metalhead crawling through a desolate landscape with Andrzej Wróblewski’s Three Tombstones (1956) and Witold Wojtkiewicz’s All Souls’ Day (undated), the latter depicting a mysterious night celebration around a cross. On the adjacent wall, Antanas Žmuidzinavičius’s mesmerizing portrayal of a lamenting man (Grief, 1906) neighbors a marvelous plaster sculpture by Bolesław Biegas (Powerful God, 1901), portraying a bony, hollow-eyed character embraced by a swooning figure. Next to it, a blowup of a work by Waliszewska – of a pale white-haired boy holding a scythe and riding a skeletal horse, serves as background for the two. The contrast between the large-scale copy of the contemporary piece and the historical originals adds a further layer to the show, encouraging viewers to reflect on the circulation of images in the age of digital reproduction.

Aleksandra Waliszewska, “Unititled,” 2020

The centrally located chapter, “Catmania & Animalia,” is reserved for the artist’s inner circle. The artist’s family – great-grandmother Kazimiera Dębska, grandmother Anna Dębska, and mother Joanna Waliszewska, all artists themselves – is represented here with their work. The sculptures of young animals by Anna Dębska are particularly striking: the Lambs (1960s–70s), Little Bison (1950s–70s) and Young Lynx (1960s–70s) are all cast in bronze – a material often reserved for depictions of grandeur. Here, they carry a sense of tenderness and the sculptor’s attention toward her subjects, perfectly capturing the mix of curiosity and insecurity – sensations so present in every youngling’s mind. Another personal highlight in this chapter is a captivating, rarely exhibited tapestry by Wanda Bibrowicz, St. Francis’ Sermon to the Birds and Fish (1914), depicting the saint surrounded by pelicans, penguins, terns, and seagulls.

But the main heroine of this section is Waliszewska’s cat, Mitusia, frequently inhabiting in the artist’s idyllic landscapes. Mitusia, like many of Waliszewska’s creations, is a puzzling, almost mythical creature. At times, the pet’s sensitive side is on display: contemplating nature, playing the flute, or chasing butterflies. Yet, in another scene, she is shown devouring the organs of her human caretaker. Waliszewska flawlessly deploys ambivalence: the motives and objectives of the protagonists of her works are never clear. This is most visible in the exhibition chapters on “The Figure of the Upiór,” dedicated to a class of Slavic wraiths walking along the line bordering the world of the living and realm of the dead, and “Matriarchy, Madonnas, Mermaids & Maidens,” dominated by female figures, frequently caught in the course of mysterious and mystic activities, and “Enchanted Landscapes: Forest & Swamp,” featuring in-between, liminal spaces where death and life meet. Here again, Waliszewska’s depictions of lustful wraiths, sinister hybrids, and haunting auto-portraits are accompanied by works from very different registers, ones that have already been dignified by art history. Magical landscapes by Mikalojus Čiurlionis (Fairy Tale (Fairy Tale of a Castle), 1909), hang next to Emīlija Gruzīte’s Fantastic Landscape (1910), a composition in blue, depicting a dreamy mountain view that also features giant anthropomorphic figures. On the opposite wall hang Waliszewska’s portraits of malignant kelpies, emerging from a somber background, their eyes on the prey.

Marian Wawrzeniecki, “Holy Entrance to the Slavic Mystery Place,” 1920

“Dark Arts” is a show full of wonders. The historical works selected by the curators are a precious and gratifying sight. Yet, some of them –such as the doll-like depictions of women by Stefan Żechowski (Balbina on the Heath, 1936), Bolesław Biegas’s sensual allegories (Ritual Dance, 1927), or Marian Wawrzeniecki’s Slavic reveries (Holy Entrance to the Slavic Mystery Place, 1920) – remain problematic when presented without comment. It is hard, almost impossible, to solely appreciate their visual layer in the context of the recently rediscovered right-wing fascination with “Slavic pride,” or the vicious attacks on women’s rights orchestrated by Poland’s ultra-Catholic government (the near-total ban on abortion announced in 2020 being one of the most fateful examples), as they might be seen as reinforcing a misogynistic attitude toward the female body. A beautiful life-sized wooden sculpture of a young woman by Bogdan Ziętek (Monkey, date unknown) is a case in point. The aesthetical allure of the carefully carved and wonderfully polychromed figure, dressed in underwear and sitting in an impossible pose on the white museal pedestal, is unquestionable. Synchronously, the piece accommodates an ominous, darker sense: it embodies the reifying power of the male gaze, reducing its woman subject to an obedient fantasy.

This is the ambiguity of pure visuality at work. Waliszewska’s reinterpretations of certain art historical tropes and motifs may be read as an opposite example of a misogynistic worldview which many of the Symbolist artists shared. Indeed, her works are full of representations of domineering females, vengeful vamps, and triumphant dames. But even though the artist restores the agency of her female protagonists, she “distances herself from the heavy political burden of ‘the F word’” [2] . Nonetheless, art is always political and never without consequences – it either reinforces the status quo or challenges it. Refusing to acknowledge this mechanism means that the restoration of women’s agency present in Waliszewska’s work may be temporary – effortlessly appropriated and, ultimately, taken away.

“The Dark Arts: Aleksandra Waliszewska and Symbolism from the East and North,” Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, June 3–October 2, 2022.

Ewa Borysiewicz is a freelance art writer and curator based in Warsaw.

Image credit: Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, photos Daniel Chrobak

Notes

| [1] | Alison M. Gingeras, Natalia Sielewicz, eds., The Dark Arts: Aleksandra Waliszewska and Symbolism (Warsaw: Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, forthcoming), 26. The quotation and page number are taken from the Polish edition of this same catalogue (2022). Quotation translated into English by the author. |

| [2] | Ibid., 26. |