IF THE SHIRT FITS Fionn Meade on the OFF-Biennale Budapest

Slavs and Tatars, “Friendship of Nations,” 2025

In the weeks prior to the opening of this year’s iteration of OFF-Biennale, “Poems of Unrest,” Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and his Fidesz majority ruling party passed anti-gay legislation that outlaws any public expression perceived to be in support of LGBTQ communities or any related issue, thereby expanding their anti-LGBTQ legislation of 2021, which equated homosexuality with pedophilia. This new measure includes a ban on the upcoming Budapest Pride Parade and legalizes government use of facial recognition to levy fines equivalent to 500 euros on any parade or protest attendees supporting Pride or other assemblies, and further allows for arrests of any perceived organizers, rendering their actions punishable by up to a year in prison.

And yet, “Poems of Unrest” unexceptionally includes queer ecologies among the many themes to be found across its international range of more than 70 artists and 15 sites. Not difficult to spot, an opening-week project led by artist Rachel Fallon, Aprons of Power (2018–25), enacted female and queer visibility, with 20 local performers lifting hand-sewn and quilted aprons, each garment revealing on its underside a variation of “I AM PRESENT,” along with an open eye and a color of the Progress Pride flag. Always done in unison, the gesture was repeated on the steps of the National Museum, the Great Market Hall, and the Hungarian Radio building; the performers walked from station to station, and attendees met them at each.

The backdrop of growing political tension attests, in part, to why OFF-Biennale – formed as it was by a group of six experienced curators in the wake of Orbán’s 2014 reelection – set its intent to work without state funding or partnership with state-run initiatives. Decentering curatorial authorship, this year’s curatorial team expanded to 10 and continued its expressed and ongoing aim of rebuilding the foundations of the independent Hungarian art scene and a “culture of democracy through art.” [1] Pragmatic and utopian by equal measure, OFF underscores the precarity of artistic expression under Orbán while it also builds up a resilient network of small individual donations and corporate support, project-specific funding from ministries outside Hungary, and backing from a few key international trusts and foundations committed to art, democracy, and human rights – as with the Sigrid Rausing Trust and Between Bridges, two of this year’s funders.

As if on cue, a further piece of sweeping legislation was put to the Hungarian parliament during my visit; it essentially embodies Vladimir Putin’s “foreign agents” bundle of legislation, initially passed by the Russian Duma in 2012. If voted into law in Hungary, this would make all independent organizations and media with ties to support from outside the country liable to investigation, crippling fines, and enforced closure, even for support as small as five euros, rendering OFF’s sustainable model of independence a virtual impossibility.

Assuming he succeeds in passing the law in September, Orbán will have fully transitioned from his self-described slow-boil “cooked frog” illiberal methods of dismantling democracy, steadfastly enacted during his 15 years in power and lauded by Steve Bannon and Russell Vought as modelling “Trump before there was a Trump,” into an unabashed autocratic severity he now proudly touts as a Christian Nationalist Democracy based on the Christian family model. [2] It amounts to an authoritarian model the Hungarian political economist Bálint Magyar has termed the fulfillment of a post-communist “mafia state,” one that is now increasingly brazen and boldly tightening its grip in Budapest, and a model much-heralded within the White House and beyond. [3] As elections approach in 2026 and Orbán’s Fidesz party lags in the polls behind a popular new challenger from the opposition, it’s clear that a full slate of repressive tactics is now in place to stay in power.

Stepping up to but also deftly skirting what cultural theorist Achille Mbembe has termed the aesthetics of brutalism, wherein “the state of exception becomes the norm and the state of emergency, permanent … maximally used to multiply states of lawlessness and to dismantle forms of resistance,” “Poems of Unrest” chose to play its themes directly off the far right’s constant rhetoric of “security” and “protection” in developing its exhibition, performance, and program responses. [4] Taking place within a gathering storm of security measures and legislation that Fidesz justifies due to purported threats from LGBTQ, migrant, and foreign others, particularly resonant exhibition strategies included a widespread use of absurd humor and subversive language, a deeply felt focus on the impact of current wars and surveillance tactics, and an overall emphasis on collective resilience.

Gypsy Criminals, “We protect,” 2025

Works throughout splayed open the political language of new legal exceptions, moral panics, and emergency measures increasingly synonymous with the far-right flag of security flashing across screens and election campaigns everywhere. A biting example included satirical paintings from the Budapest-based group Gypsy Criminals – self-described as two artists and a small dog – utilizing what they call “Romadada” in stitching together, inverting, and cutting up the Orbán regime’s legislative declarations to accompany cartoony paintings depicting a national superhero charged with protecting us from all threats domestic and foreign. Resembling the stocky physique of Viktor Orbán himself, the masked and caped hero recalled Mexican luchador combatants but also the balaclava-clad thug units of contracted state repression and far-right militias. Twisted from actual Fidesz materials, the absurd slogans include phrases translating to “WE PROTECT OUR DICTATOR FRIENDS FROM OUR DEMOCRATIC ALLIES” and “WE PROTECT HUNGARIAN CHILDREN FROM CRITICAL THINKING,” as well as “WE PROTECT UTILITY CUTS FROM REAL WAGE INCREASES.” With education and healthcare budgets gutted, hospitals broken, EU infrastructural grants and contracts pocketed by Orbán’s crony circle to the tune of hundreds of millions of euros, hyperinflation among the highest rates in the EU, and economic GDP per capita among the lowest, the wordings capture the impoverishing spirit and actual results of Orbán’s disastrous rule as the true race to the bottom it is. The artists’ name itself repurposes the long-standing Hungarian racist catchphrase “gypsy crime,” found in countless government policies, and incisively lampoons the absurdities of Fidesz rule by flipping the scapegoating term gypsy criminals into a loudspeaker of dismissive laughter. [5]

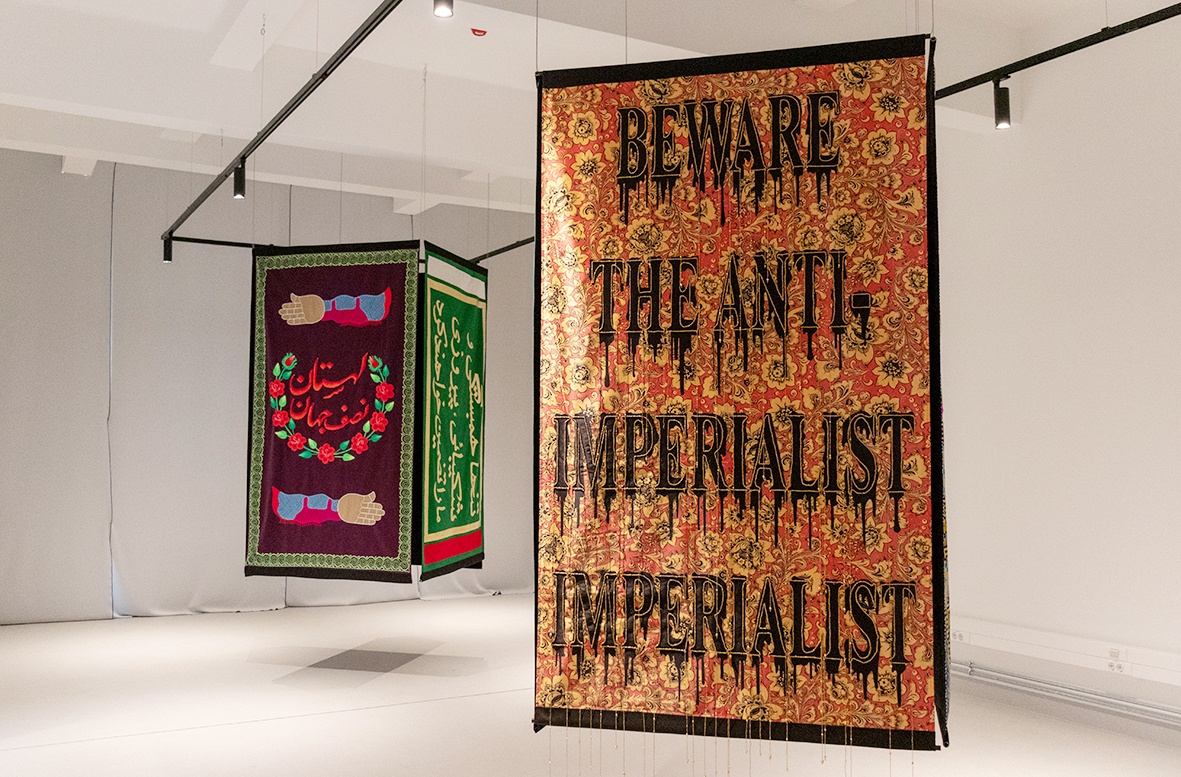

Larry Achiampong’s Detention series (2016–25) likewise deployed warped phrasing – by turns haunting and comic – via repetition across the familiar chalkboard surfaces of old-school punishment meant to make rote and internal moral rectitude and anticipatory obedience. Untethered here, Achiampong hijacks the format to launch poetic ruptures, as chalked repetitions like “THE DEEPER WE’RE BURIED THE TALLER WE’LL GROW” and “LIKE RICH MOFOS JIZZING TESLAS INTO SPACE,” or “NOW WE’RE ALL TRAPPED INSIDE A CARTOON” rewire the caustic condition of social media and online message boards into inane foreboding. A nearby installation from art collective Slavs and Tatars, Friendship of Nations (Banners) (2011), circulates a series of textile works that collapse and recombine sayings from the Iranian Revolution of 1979 and the Polish Solidarność movement of the 1980s, including the farcical union phrase “HELP THE MILITIA – BEAT YOURSELF UP!” deployed to mock life under martial law in early ’80s Poland, while another banner read “BEWARE THE ANTI-IMPERIALIST IMPERIALIST,” a mashup of partisan cliché combined to show how such freighted terms are weaponized in today’s populist climate.

Katarina Ševic, “News from Home, roof tiles,” 2025

In News from Home, roof tiles (2025), Katarina Šević takes the raw material of newspapers reporting on the ongoing protest movement in her native Serbia – including publications from Germany, Serbia, and Hungary across the political spectrum – and pulps them into papier-mâché. Using a traditional method for clay brickmaking, Šević shapes the tiles to the contour of her upper thigh, constructing a low-slung sculptural overhang that offers no shelter, and only the occasional catch-phrases – “amoral” for example – spat out from the flow of processed reporting. More overt agitprop tactics continue in Dorottya Szonja Koltay’s installation Releasing Burdens (2025), as comically fashioned construction hard hats, black-and-yellow caution tape, and the off-limits vibe of police barricades and demarcation lines are made into props. These occasion loosely scripted performances in the gallery, and in the street, where the audience can join performers in taking advantage of a shaggy carpeted “UNLOADING” dock to lay down their burdens, or hoist “don’t carry it” poles with oversized red hand extensions. They can also learn cathartic songs and dances that flip the coercive signals of “do not enter” into a joyful participation, a detour around the trappings of security that reminded equally of Ulrike Ottinger and Mike Kelly.

Dorottya Szonja Koltay, “Releasing Burdens,” 2025

Elsewhere, a Second World War–era air-raid bunker in the city center billeted an affecting group of moving image works that included Open Group’s installation Repeat After Me (2024). Centered on displaced Ukrainian civilians giving testimony of having survived Russian attacks, the specific sounds of war – from sirens, drones, planes, and artillery explosions – are demonstrated after each recounting so that the audience can also learn by heart and repeat the sounds via a setup of standing mics. Recorded in camps, hotels, dormitories, and temporary shelters across Europe and beyond, these refugee accounts echo like harrowing warnings to the present and future. A mood of aftermath, repeat incursions, militarized occupations, and the spread of systemic surveillance inflected presentations across other venues, including the matter-of-fact tone of Forensic Architecture’s video “No Traces of Life”: Israel’s Ecocide in Gaza (2023–24), tracing through satellite and aerial imagery the Israeli military forces’ targeting and crushing destruction of orchards, collective farms, and greenhouses throughout Gaza since October 2023 – bombed, bulldozed, and replaced with earthworks to buffer and reinforce new military outposts. The resulting map shows Israeli forces enacting infrastructural food scarcity and establishing mined zones where orchards once stood, a landscape of siege and genocidal conditioning that will last long into the future. Oleksiy Radynski’s Chornobyl 22 (2023), meanwhile, speaks to a different never-ending disaster zone, as Radynski interviews the team of workers protecting the site of the 1986 nuclear fallout during its occupation by Russian military forces at the outbreak of war in Ukraine in 2022. As the team is forced to play host to an occupying regiment over three weeks, the threat of another large-scale contamination stirs specters of Soviet-era control of Ukraine, even as Radynski’s approach accents furtive moments of humor and small acts of resistance recounted by the workers, narrating their ordeals within the relatively bucolic containment zone that surrounds Chornobyl.

Open Group, “Repeat After Me,” 2024

With Tytus Szabelski-Różniak’s photograph As Above, so Below (2025), the spread of a silent militarized presence is indexed by a large antenna from Elon Musk’s Starlink satellite network rising up behind a picturesque farmstead barn in the Polish countryside. And, in Kateryna Aliinyk’s allegorical oil painting Death on a Summer Afternoon (2024), her native region of the Donbas in Ukraine is reimagined as slowly emerging from the toxic mix and blighted conditions left behind, surreal plant life grasping on to scorched earth – contaminated groundwater, unexploded mines, and scattered remains underfoot – new noxious growth sowing itself in the sun.

And yet many of the most resonant works on view gestured toward futurity through moments of cooperative resolve. Robert Gabris’s video and sculpture installation Asylum – a Poem of Unrest (2024–25), from which the exhibition edition takes its overall title, envisions a fantastical human-insect collective with newly incubated protective exoskeletons. Ornate costumes made of cut paper, textile, and delicate drawing bring in elements of Gabris’s own background as Roma and queer to invent a sort of future indigeneity and emergent hybridity, as an accompanying poem irreverently calls for new forms of creative asylum. Togetherness and readying as a group traded places with the many documentary and performative works on view. One such image surfaces indelibly in Róza El-Hassan’s free-standing sculpture How to Proceed / Human Collective (2017); combining bits and scraps of milled lumber, a roughly carved and minimally painted group of humans and animals emerge in rough-hewn outline, appearing to hesitate on the precipice of setting out, gathering strength for the uncertain path to come.

Róza El Hassan, “How to Proceed/ Human Collective,” 2017

The work stayed with me while attending a protest in front of the Hungarian Parliament against the foreign agents legislation – the new bill bears the Orwellian title “On the Transparency of Public Life.” El-Hassan’s collective hovered in mind as I stood in the midst of a bevy of signs among the ten thousand protesters that made perfectly clear just how Orbán and his so-called Hungarian Model is understood locally to stem from following Moscow’s lead. Not lost on the crowd is the ironic twist of how the mafia state has migrated west from Putin’s 25-year reign to Orbán and onward to Trump’s MAGA movement, now scaled up American-style to celebrate a motley global consortium of competitive authoritarians and plutocratic grifters, increasingly on the take everywhere.

As extolled by a vibrant and salutary installation in Bura Gallery – a biennale venue devoted to contemporary Roma artistic production – the crucial turn needed is one away from atomization and its nihilistic fatalism and withdrawn wait-and-see individualism – for this is de facto anticipatory obedience – but also a simultaneous turn away from neatly personalized artist branding, tailored and formalized identity constructions, and the glut of artist-as-storyteller and provider of individual mythologies and cosmologies careful to avoid any real world political ties. Indeed, the unruly arms of Aliz Farkas’s sculptural garments reach many-tentacled outward from singular torsos, including the knitted Stretch as far as your blanket can reach and stitched up If the Shirt Fits (both 2025). Such gestures can invite each of us to step fully back into the fray, constellating in play and out of necessity beyond isolation, in opposition and with non-conformity, in mutation and toward solidarity, and always, in willing coalition and growing unrest. If the shirt of resistance fits, it’s past time to put it on.

“Poems of Unrest,” OFF-Biennale Budapest, June 8–15, 2025.

Fionn Meade is a writer and curator living in New York.

Image credits: © OFF-Biennale Budapest Archive; photos 1.- 2. Flóra Dobos: 3. - 6. Dávid Bíró

Notes

| [1] | OFF-Biennale Budapest’s organizational statement of intent can be found under What Is Off? on their website. |

| [2] | Orbán outlines “demography, migration, and gender” as the primary targets to scapegoat and demonize within his “Christian family model” political project, often equating his targets to those of Great Replacement race theory widely espoused by white nationalists within the MAGA movement. See David Edgar, “Cooked Frog,” review of Tainted Democracy: Viktor Orbán and the Subversion of Hungary, by Zsuzsanna Szelényi, The London Review of Books 46, no. 5 (March 2024): 31. |

| [3] | For an outline of Magyar’s analysis of the Hungarian mafia state and its origins in Valdimir Putin’s regime, see Masha Gessen, The Future is History: How Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia (Riverhead Books, 2017), 386–87. |

| [4] | Achille Mbembe, Brutalism (Duke University Press, 2024), xv. |

| [5] | “Hungary is now one of the poorest countries, and possibly the poorest, in the European Union. Industrial production is falling year-over-year. Productivity is close to the lowest in the region. Unemployment is creeping upward. Despite the ruling party’s talk about traditional values, the population is shrinking.” Anne Applebaum, “The Hungarian Model,” The Atlantic, May 2025, 16. |