CRITICISM AS FAN FICTION By Francis Whorrall-Campbell

River L. Ramirez, illustration from Charlie Markbreiter’s “Gossip Girl Fanfic Novella,” 2022

What genre of writing is produced in response to a cultural object? Is written from a place of love and admiration, sometimes indignation and disappointment, toward that object? What text might offer improvements, alternatives, ways the object could have been done better or more to the writer’s satisfaction, but ultimately may generate cultural and/or financial capital for the original work? If you answered fan fiction, you’d be correct. If you answered criticism, you might also be correct.

Fan fiction and criticism are unlikely doppelgängers. Fan fiction is a mode of amateur creative writing produced by fans based upon an existing cultural object (e.g., a film franchise or pop group) but unauthorized by the original creator of that work. Criticism is a professionalized – although not necessarily remunerated – field of discourse production that seeks to understand and establish the historical and/or cultural significance of a work of art or cultural object through analysis and interpretation. These modes of writing are seemingly polar opposites – one “low,” the other “high”; one “private,” one “public”; “amateur” or “professional.” Yet opposite poles are joined through the core, and looking at the ways in which these genres touch or overlap reveals something about the way in which cultural attachment and desire operate.

Breaking down the questions with which we began, precisely what similarities can we note? First, that both fan fiction and criticism take as their starting point already existing and complete works of art. Neither are produced ex nihilo but in dialogue with another cultural creation. Second: this desire to respond also marks a certain libidinal investment in the original object. While the emotional valence of this attachment might be differently expressed, the orientation is clear – obsessive even – to an outside observer. Third: such investment is often sparked by a longing or lack of resolution. The writing is born out of a desire to add something to the original in order to complete it, improve a defect, answer a question or emphasize something admired. And fourth: this addition is labor. The writing adds value to the original object, providing a kind of authorized or unauthorized marketing, giving the object’s cultural and market capital, prolonging its shelf life, and potentially increasing its exchange value. The text also produces a social aspect to consumption, expanding the base of potential consumers, creating a community around it or the original, which can be marketized.

By now we have a picture of a Venn diagram where the left circle is labelled fan fiction, and the right labelled criticism. What would happen if the two circles fully overlapped, becoming one and the same? Luckily for us, someone has already made a start on the answer.

Cover of Charlie Markbreiter’s “Gossip Girl Fanfic Novella,” 2022

Charlie Markbreiter’s 2022 Gossip Girl Fanfic Novella is exactly what the title suggests it will be. If there is a surprise, it’s that the book consists of three parallel narrative threads that interweave across the chapters (although anything goes with fanfiction): fanfic of the original Gossip Girl series (which aired in the US from 2006 to 2012); the invented story of Gordon, a trans man and writer on Gossip Girl 3, set in the near future; and critical essays on topics ranging from the live-action Lion King, a possible feud between Dua Lipa and Charli XCX, and Paris Hilton’s The Simple Life.

Gossip Girl Fanfic Novella is birthed out of the original series. It follows the same characters we love (or love to hate), and it takes place in the same city, but that’s where the similarities end. Like other fan fictions, copyrighted characters and settings form the set pieces for a new plot. Markbreiter invents upon what the showrunners have built, while also offering a critical commentary on this world of celebrity, wealth, and power. The criticism folds into the fiction, the subject of one bleeding into the other. It is almost as if, by splitting them formally apart, the text allows the reader to appreciate how close these modes actually are to one another – mirror images, almost. The shared object of the fan fiction and the criticism is not so much the show Gossip Girl itself as the fantasy image of America it produces and reflects as “normal,” where normal just means white and wealthy.

Nate (the “Golden Boy” and son of a business magnate) emerges from the cast of Upper East Siders as the main character of the fanfic portion of the novella. Markbreiter recasts him as a trans boy – how better to show how race and class give access to normalcy? In the fanfic, the narrative voice that reveals (or creates) Nate’s transness explicitly reflects on how his father’s extreme wealth allows Nate to transition in a time (1998) and period of his life (childhood) when doing so was not only rare and expensive but out of the public eye, something that allowed him to be “not just normal but regular.” [1] This conclusion is echoed in a chapter that glosses Jules Gill-Peterson’s Histories of the Transgender Child, which reminds us that early experiments in childhood transition were “mediated by race and class, as is everything.” [2]

The voice affected for this gloss is suffused with affectless irony. It’s the same voice that Markbreiter imagines ringing in the head of the rich kids during the fan-fiction chapters (but perhaps a little more self-aware). The fanfic writer and the critic share not only the same object but also the same tone. In Ugly Feelings, Sianne Ngai describes tone as a “feeling” that emerges from the form of an object. [3] It is created somewhere between the felt object and the feeling reader/viewer: a kind of mutual attachment or orientation between us and the thing. In Gossip Girl Fanfic Novella, criticism and fan fiction share an attachment to their shared object. This might be best characterized as longing. Gossip Girl Fanfic Novella is haunted by the ghost of Lauren Berlant. Literally.

During a moment of hormonally-induced psychosis at the Plaza Hotel in New York, Nate witnesses the dead Lauren Berlant speaking to him through a television set. Berlant reveals that the expensive bootleg puberty blockers Nate’s parents got him during the 1990s have been turning him into his father. The thing you want stops your flourishing. Berlant identifies this pillar of the American dream through the concept of “cruel optimism.” The object (wealthy white masculinity, i.e., being normal) is bad for you, but desire isn’t, so the remedy – and the work of critical theory – is to use desire to change the object.

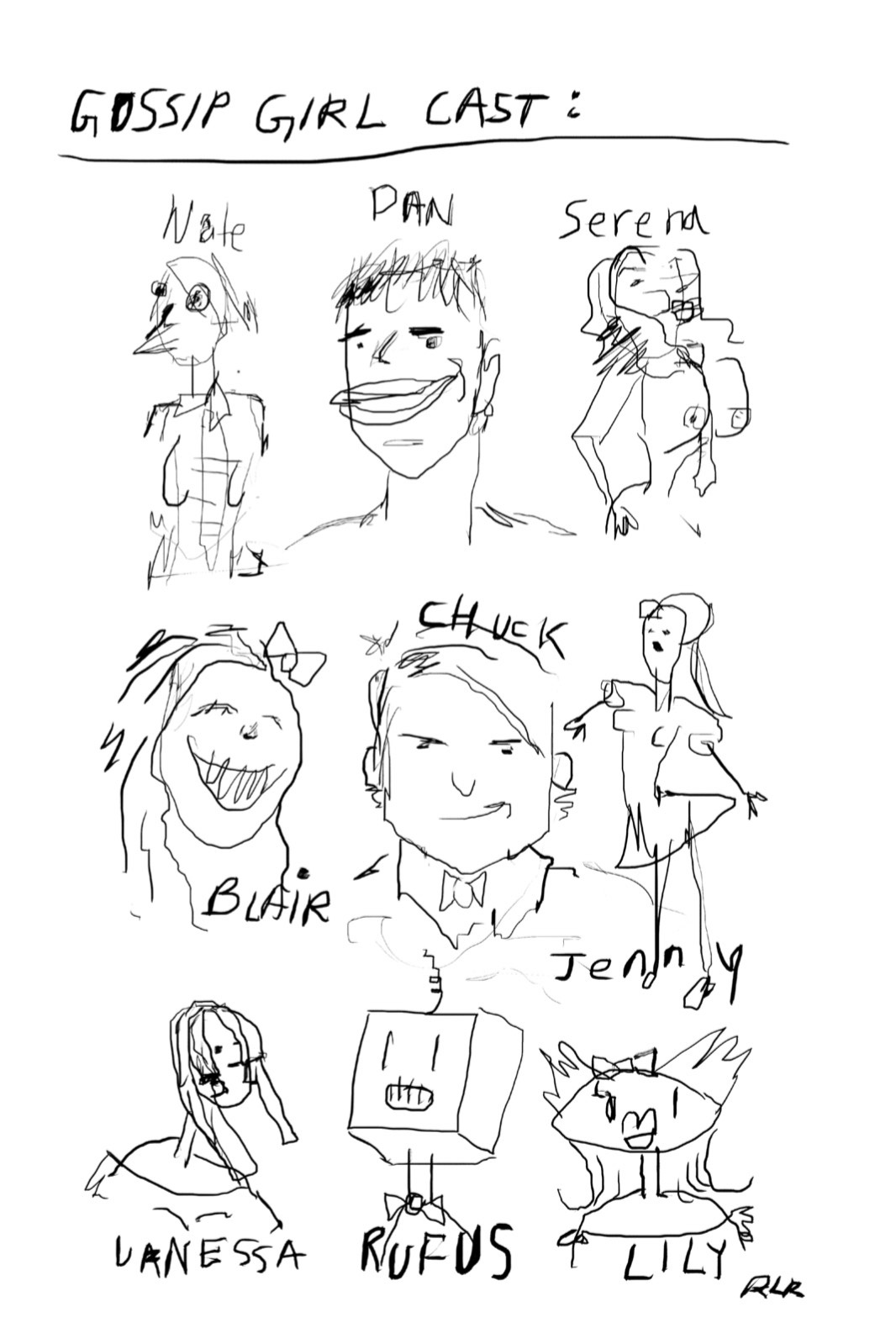

River L. Ramirez, illustration from Charlie Markbreiter’s “Gossip Girl Fanfic Novella,” 2022

The fan fiction portions of the novella have already set this process in motion, altering the television show’s script to fulfil the writer’s niche wishes for the series and for America. To insert a trans main character into a past season and speculate a trans writer on a future one reads like wish fulfilment for both cultural representation and job opportunities. These are modest desires: the happy endings afforded Nate and Gordon are mundane. By the end of Markbreiter’s book, Gossip Girl 3 is renewed for a second season and Gordon attains some level of financial stability, while Nate enjoys a chat with the now-not-dead Berlant at a coffee shop.

The mundanity of these wishes bespeaks perhaps a fear of too-great hope, lest one not achieve it. The power of normalcy is strong: even when you know it is a self-limiting belief, it is hard to let go. The critic, too, can be plagued by the fear of wanting “too much” for one’s context. In a 2019 interview, Lauren Berlant revealed that their transness was no late-in-life conversion: “The commune I lived in when I was in high school, Twin Oaks, had a gender-neutral pronoun: Co. And I used it for years. And got my ass handed to me in grad school for being pretentious. So [I] stopped.” [4] It might be gauche to read Berlant’s investigation into the destruction wrought by desire through a biographical lens, but perhaps you do become a critic to understand the object that rejects you.

Or maybe you write fan fiction. Fan fiction has the advantage of being able to stage the change the author wishes to see in the (fictional) world, not simply argue for it. A favorite trope within fan fiction is the “self-insert,” by which the writer inserts herself into the world of the text she’s rewriting. This is perhaps explained by a desire to see things that weren’t represented in the original, like queer characters, or characters of color, or the writer’s very particular desire to sleep with Draco Malfoy. But fans that do this are often discarded by the creator of their obsession. Markbreiter relates the story of Steve Vander Ark, the creator of the unauthorized Harry Potter Lexicon. Upon the release of the final Harry Potter book, Vander Ark was so offended by its epilogue that he suggested fans “throw it out” of the canon – declare that it was not “real” and write their own series ending.

When Vander Ark tried to publish the Lexicon, he was sued by J. K. Rowling, despite the fact that she admitted to using it herself to keep up with the lore of her own universe. Fan fiction authors had value to the original but rarely receive financial benefit themselves. Critics also risk that their work will add symbolic value to an object rather than deconstruct the object and the way value is apportioned – often to the diminishment of their own remuneration. Is it possible to talk people out of their tastes, which is to say their desires? Nate still wants to be a man. Viewers of Gossip Girl still want to be rich and/or famous (even if just a little bit).

Let’s add another question to the opening. What writing is produced as a result of the affective experience of cruel optimism? Markbreiter’s answer: fan fiction and criticism, of course.

Francis Whorrall-Campbell is an artist, writer, and sometimes art critic from the UK. Working across text, sculpture, and the digital, their work explores and advances a trans poesis, probing the link between making an artwork and making a (gendered) self – or how art and writing can be tools for transition. This practice is guided by research into materialist histories of trans becoming, including histories of DIY transition, mutual aid, trans medicine, trans aesthetics, and other conditions that promote or inhibit trans survival.

Image credit: Courtesy of Charlie Markbreiter and Kenning Editions

Notes

| [1] | Charlie Markbreiter, Gossip Girl Fanfic Novella (Chicago: Kenning Editions, 2022), 30. |

| [2] | Ibid., 10. |

| [3] | Sianne Ngai, Ugly Feelings (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007), 43. |

| [4] | Lauren Berlant, “Intentions: An Excerpt from *On the Inconvenience of Other People*” [2022], New Inquiry, October 25, 2022. |