FIRE IS OF THE IMAGINATION Hannah Gregory on Bassem Saad at Triangle – Astérides, Marseille

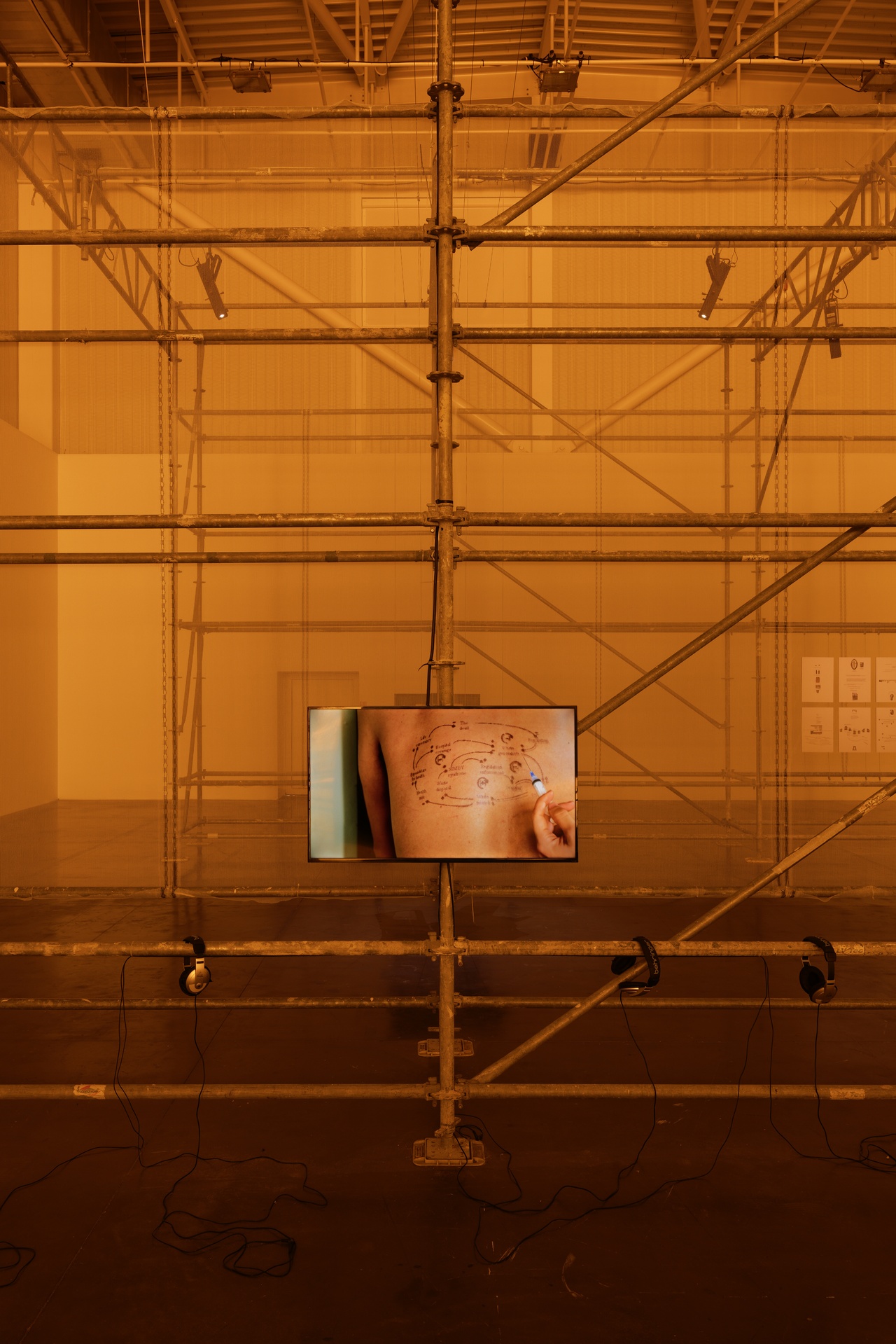

“Bassem Saad: Smoke in the Next City,” Triangle-Astérides, Marseille, 2023, installation view

The tinted panes of the window installation on the interior glass façade at the end of the “Panorama” room, curated by Triangle – Astérides, suffuse the whole of Bassem Saad’s exhibition, “Smoke in the Next City,” with a pale orange light – like a durational sunset, or the burning embers of property and police-car interiors post-riot. The hue that envelops the artist-writer’s first solo institutional show is both toxic and romantic, seductive and oppressive. Through the window frames, behind their intertextual fragments superimposed as poetic-political slogans (“ANOTHER END TO FRENCH REVOLUTION AFTER COLONY IN PRISON”), lies the flat roof of the Friche la Belle de Mai public arts complex, before the cités of Marseille’s northwestern districts, beneath clouds blown in by the mistral and turned tumultuous by the flaming filter. By the time I am writing, the skies of New York are aglow with an almost identical orange-lit smog, blown down the coast from wildfires in Canada: the smoke not of the next city of the exhibition’s title, but of now.

When I visit Marseille from Berlin, where Saad also currently resides, this particular color connotation to atmospheres of climate change hasn’t yet arrived. The route to the exhibition space within the vast complex – a former cigarette factory that was once the working hub of the city’s third arrondissement – was without wayfaring cues, like a dream where you can’t quite reach where you want to go. Much of the work in this survey of the artist’s early production emerged from the retrograde processing and relative stillness of the aftermath of revolt; against passive viewing, its spirit invites un-rest.

Scaffolds partially divide the space into four sections of unequal size and serve as provisional structures for the installation of Saad’s films and text-based works without controlling movement, insulating sound, or blocking line of sight. I am drawn to plant myself on cushions set in front of the main projection of their most recent film work, Congress of Idling Persons (2021). The chants from Congress bleed into the viewing of the other works, just as light from the outside world intrudes upon the screen – or as the haze left over from the Lebanese uprisings of 2019–20 infiltrates the film’s initial indigo theater-like set, an otherwise enclosed space for post-protest conversation. I later learn that the installation was intended to evoke a drive-in cinema (more romance), [1] and indeed, the Mediterranean port cityscape of Lebanon’s former colonizer is impossible to ignore beyond the film’s frame. This structural layering, which splits focus between the works and their urban context, asks viewers to hold multiple, often contradictory, elements in mind at once, and makes for an art that refuses to forget its outside.

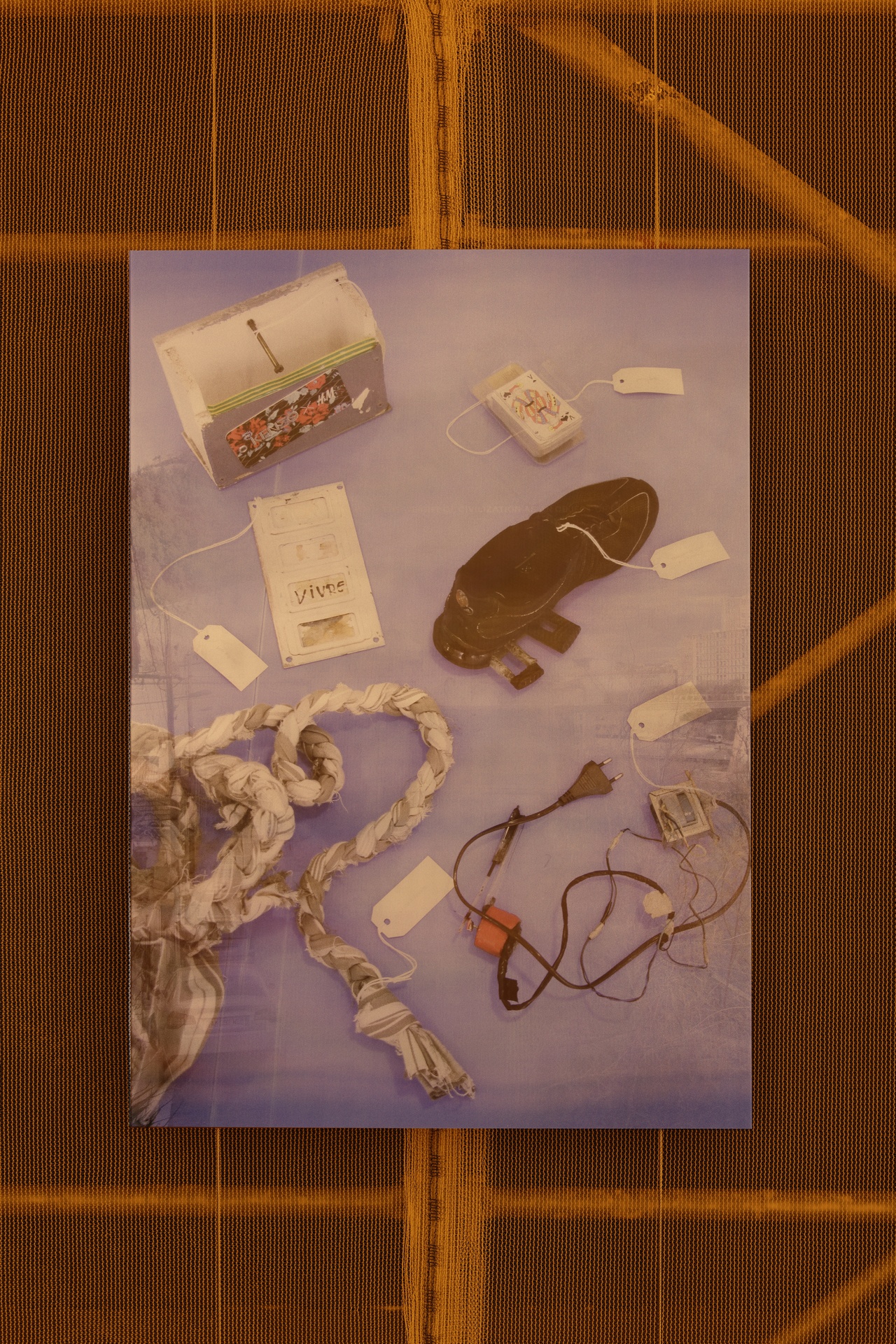

Bassem Saad, “Kink Retrograde,” 2019–22

I enter the screening of Congress as the artist’s shots of central neighborhoods in Beirut following the port explosion – washed-out sky; silvery, fallen olive trees; cream-colored buildings with blasted windows – are spliced with high-energy phone-camera footage, and its integral sound systems, from the Lebanese uprisings. The interruption of the horizontal film images surveying the streets by these vertical handheld views turns the frame into a quasi triptych: the pale colors of retrospection cede to the live witnessing of the “vengeful joy” of the riot. [2]

“WE HAVE BARELY GOTTEN USED TO LOOTERS AND RIOTERS FILMING THEMSELVES” read the intertitles, which punctuate Congress’s various settings and types of footage related to collective struggle: staged, found, and documentary; an intellectual’s book-lined study; the 2011 Syrian Revolution; New York during the George Floyd uprisings of late spring 2020… Although no “I” appears at this level of the script yet, these all-caps lines introduce the writerly identity (both Arabic and English) of the Beirut-born artist, and their relation to the events represented. While writing brings some remove, dialogues between interlocutors of various Lebanon-dwelling backgrounds, whom Saad met through political and social life in Beirut, comes with the closeness of comrades. Extending outward from the social network, it’s a mode of production that rallies the force and voices of the crowd. Palestinian writer Islam Khatib and labor activist Mekdes Yilma reflect on agency, haunted psyches, and (non)belonging as refugees or migrants amid revolt. Musical artists Rayyan Abdel Khalek and Sandy Chamoun (whose incendiary sounds send off the film’s close) reflect on their participation in local and regional uprisings surrounded by the paraphernalia of protest, used tear-gas canisters mocked as butt plugs. Chamoun tells of her stay in Cairo at the time of the 2011 Egyptian revolution; Khalek says he can’t relate to going overseas for activism: “There isn’t exactly a scarcity of causes in Beirut.” Cut to the NYC/BLM segment, and a comment from Saad on their presence there: “IN NEW YORK, I WAS A MERE BYSTANDER.” During the exhibition’s span, which coincided with unrest in France against pension reform, I watched Bassem’s Instagram stories of young anti-Macron protesters listening to gabber and setting bins on fire in a central square: a similar, but not identical, close-to-the-crowd view as when rioters have filmed themselves in Lebanon, Syria, or the United States. The medley of testimonies in Congress, along with the engaged first-person part of its script, effectively hold the tension between direct involvement in revolutionary action and the distance required for – the filter imposed by – the making of art.

Where positions between “home” and away, here and there, turn on the axis of the artist in Congress, two earlier films displayed in smaller format come out of Saad’s formative years in Beirut, and show a foundational approach of editing legal and critical-theoretical registers with original writing as a rhythmic overlay to visuals grounded in place. Saint Rise (2018) – a title like a Knowles-sisters duet but actually taken from a Levantine Christian hymn – depicts the erection of a supersized religious statue on Mount Lebanon, combined with promotional footage of an unrealized “floating island” planned by the same contractor, and was made shortly after Saad’s graduation from studying architecture. The original version of Kink Retrograde (2019/2022, here re-edited with the voice-over newly read by collaborator Sanja Grozdanić in a somewhat vain attempt to perform critical distance with recent-past work) was shot on a coastal landfill constructed for the overflowing waste of the country’s garbage crisis, while Saad was a resident at Ashkal Alwan, the Lebanese Association for Plastic Arts.

In S.R., the narration aligns Saint Charbel’s inauguration with Trump’s viewing of the “Great American Eclipse” during the same week in August 2017. The movements of the allegorical characters in K.R. bring ideas of an ethereal realm down to toxic reality: “bags and bags of flaming trash … how long had their [celestial] bodies lagged behind, retrograde cycles.” In both, there is a sense of people seeking to connect with a higher system – be this the nation (or its desired overthrowing), the gods, or the solar system. But this sublime plane exists in the often absurd imagination, and remains unreached.

Bassem Saad, “Suppose that Rome is not a human habitation,” 2023

Real connectedness exists between places and peoples of this world, which – as the arrow of the “abolitionist compass” on the window, pointing in the direction of Marseille’s Baumettes prison suggests – must also end. Real connectedness comes via history and materials, which impact bodies: out-of-date French-manufactured teargas used against Lebanese protestors, mapped on the surface of the spine-brace sculpture Still many hours to be spent with mixed company at the Square (2020). Objects handmade by inmates of this same prison, since seized and now held by the city’s Museum of Civilizations of Europe and the Mediterranean (Mucem), photographs of which shimmer within the layers of a lenticular print from the series Suppose that Rome is not a human habitation (2023). Connectedness comes, again, via other people, including the many disparate, dead individuals embedded in the work: French-Tunisian murderer Hamida Djandoubi, the last person to be guillotined in Europe in 1977, again at les Baumettes, referenced in the words of Handmaiden or midwife? (2023); a nod to “the child flower seller who died beneath the building” in a dialogue in Congress; the artist’s late mother, whose imprint belongs to another low-lying sculpture including a spine brace (To my mother and a protestor detained on November 15th, 2019), the form of which linking her and her chemotherapy treatment to a protestor injured in police custody. Saad seems to flag such figures to call upon their specifically located stories, not to flatten their memory, but amid such a dense linkage of references, some details, some people, may inevitably be missed.

When looking up one of the exhibition’s more obscure references, to Hegel (the title and text of the aforementioned Handmaiden or midwife?), I instead fall across a chapter by Marx, whose persuasions around revolutionary ghosts support an approach of “awakening the dead” in a way that seems in line with the artist’s ambitions: to “[magnify] the given task in the imagination, not [recoil] from its solution in reality.” [3] For, as per the formulation of Chamoun’s lyrics in Congress, “the people are of the imagination,” [4] and art is of the imagination, too – the act of lighting a fire starts t/here. By the time I am closing this piece, riots in the name of Nahel M., murdered by Parisian police at a traffic stop, burn through Paris and Marseille each night. In its tactics of invocation, saturation, and interruption, “Smoke in the Next City” carried “the different odors of revolution” [5] on its breeze, our eyes left squinting at an obfuscated horizon.

“Bassem Saad: Smoke in the Next City,” Triangle – Astérides, Marseille, February 11–May 18, 2023.

Hannah Gregory is a writer on art, places, and relations.

Image credit: Courtesy of the artist and Triangle-Astérides, photos Aurélien Mole

Notes

| [1] | Conversation with the exhibition’s curator, Victorine Grataloup, May 12, 2023. |

| [2] | Bassem Saad, intertitles to Congress of Idling Persons (2021). |

| [3] | Karl Marx, “Chapter 1,” The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte [1852], trans. Saul K. Padover; available at: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1852/18th-brumaire/ch01.htm. |

| [4] | Sandy Chamoun, “Dreams of the Imagination” (2021). The title of this essay also comes from a line in the same track: “the fire is of the imagination” (translation from Arabic), which is part of the soundtrack to Congress of Idling Persons. |

| [5] | Adapted from Saad’s phrase “the different odors of counterrevolution,” in: Bassem Saad, “Exporting the Revolution: In Memory of Mahsa Amini (1999–2022), Mohamed Bouazizi (1984–2011), and Sarah Hegazi (1989–2020),” The New Inquiry, February 16, 2023. |