Horror vacui, David Reisman on James Siena at Pace Gallery, New York

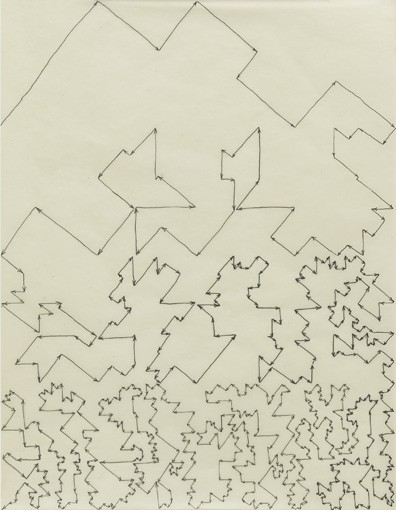

James Siena, “Triangle sequence path (second version)”, 2011, Photo by: Kerry Ryan McFate

James Siena’s artwork contains uncanny suggestions of the very specific and vast strangeness that is just beyond what we usually perceive (at least, without particle accelerators, electron microscopes or the Hubble telescope), ranging in dimensions from the subatomic to the galactic. However, rather than documenting the molecular, cellular and macroscopic expanses of existence like Charles and Ray Eames’s well-known educational film “Powers of Ten” (1968), his abstract images are, at their best, reminders of the underlying rich, complex and beautiful weirdness of our minds and the hidden structures behind observable (and explainable) reality.

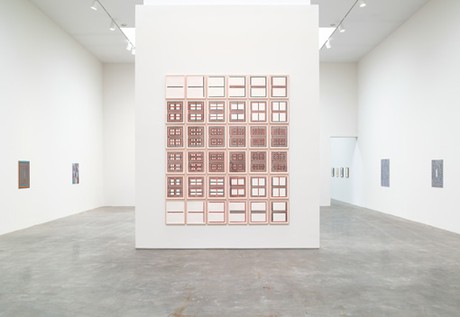

James Siena, Exhibition view, 2011, The Pace Gallery, New York, Photo: G.R. Christmas

Siena’s nonobjective art balances rational and irrational pictorial strategies, and the artist is also willing to travel down paths leading to comics-inspired imagery that borders on craziness. His recent one-person exhibition at the Pace Gallery included the relatively small, maze-like, obsessive enamel-on-aluminum abstractions he has been known for since the early 1990s – some of them consisting of one fine, convoluted continuous line (or shapes made with a continuous line), others with repeated shapes that are never interrupted in complex meanderings covering almost all of their surfaces’ available real estate. These paintings combine spontaneous and intuitive impulses with an intensely focused technique, their execution leaving almost no room for anything accidental or unintentional. Paintings like “Two Scrambled Combs” (2008), “Sawtoothed Angry Form” (2010), “Little Earthless” (2010), and “Malevolent Adolescent Form” (2010) are related to psychedelic all-over drawings, Art Brut, and Outsider Art, but are also detached from those approaches to art through their sophistication and deliberate perfectionism. At the same time, Siena’s precision isn’t as mechanical or impersonal as that in abstract geometric paintings deriving from op art or conceptual art. Though he frequently uses industrial materials, his technical approach shows an old-fashioned belief in the potential power and beauty of handmade objects, bringing to mind earlier artwork as diverse as Giovanni di Paolo’s religious landscapes and Myron Stout’s abstractions. While Siena’s titles sometimes eccentrically describe his paintings’ formal elements, they also reinforce an understanding of his expressive intentions. Twisting, folding in on themselves like cerebral cortexes or digestive systems, these paintings and drawings testify to his artistic control and craftsmanship while conveying obsessive and sometimes ominous frames of mind.

James Siena, Exhibition view, 2011, The Pace Gallery, New York, Photo: G.R. Christmas

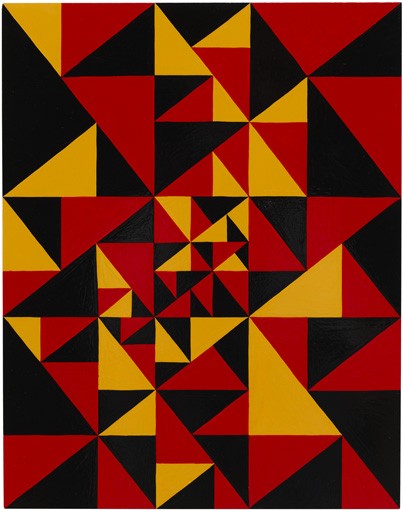

Some of Siena’s paintings and drawings are based on algorithms. By approaching the task of image making as the fulfillment of a set of rules or instructions leading to unexpected results, these works are reminiscent of conceptually oriented abstractions by artists like Alfred Jensen and Sol Lewitt, and beyond that, in their color, mood and technical polish they even harken back to paintings by synthetic cubists like Juan Gris. Unlike cubist art, however, these pieces are not schematizations of still lifes, portraits or landscapes, and they suggest (but are not directly based on) mathematically generated images like fractals. For example, in “Untitled (first triangle painting)” (2009), Siena created shapes with diagonals intersecting a rectangular grid, but the longer you look at the painting’s contrastingly colored triangles, the more you see that its geometry is organized in surprising ways. The varied arrangement of light and dark triangles creates an illusion of shallow space and unpredictable, almost musical geometry. Siena mines these ideas in a series of paintings including “Untitled (small iterative grid)” (2010), “Untitled (iterative grid)” (2009), and “Untitled (iterative grid, second version)” (2009). By following a set of rules that are unexplained though implied (supported by some of the drawings in the exhibition), and by varying composition, color, size, and complexity, they suggested a kind of imaginative restlessness and search for difficulty that contrasts with their simple, primary forms and use of limited, moody colors. “Untitled (first triangle painting)” verged on being a little too slick, but the later paintings in the series were more complex, adding a level of challenge that made them slightly less accessible but even more interesting and thought-provoking. Their structures balanced straightforward optical stimulation with a jazzily intellectual, unpredictable approach to composition. With their unusual color combinations and complicated patterns, they were mind-bending geometric counterparts to Siena’s loopy, linear maze-like paintings.

James Siena, “Untitled (first triangle painting)”, 2009, Photo: Kerry Ryan McFate

Some of the other paintings in Siena’s exhibition were also hard-edged and geometrically flat, but their compositions were strictly rectangular and perpendicular. Even though they did not have the iterative grids’ element of diagonal complication, they were similar visual puzzles, in that they made you wonder about the thought processes and problem solving that went into them. Rather than composing these with thin outlines, Siena used broader, cleanly painted and interlocking rectangles. For example, “Two Sequences” (2009) and “Two Sequences, connected” (2010) were based on limited palettes (the first, greens, and the latter, reds), but shapes that normally imply a kind of containment and create boxy limits seemed to become more like circuits and implied further complications and iterations. The elaborateness of this sequential thought process was clear in Siena’s woodcut series, “Sequence One” (2009), a group of 36 unbound woodcuts in which a series of black and red rectangles on a white background segue from simplicity to increasing complexity and back to simplicity, with the level of complication reaching a peak in the central group of images. The impulse behind this series is reminiscent of Minimalist artists’ interest in using math to generate serial imagery, but with a more personal, handmade touch and an even more eccentric edge, especially when seen in relationship to the rest of the work in the gallery.

James Siena, Exhibition view, 2011, The Pace Gallery, New York, Photo: G.R. Christmas

The exhibition was divided into a front room and a back room that included what could be seen as Siena’s “underground” material. Unlike the paintings, prints and drawings in the front of the Pace Gallery that, in their rule-based abstract imagery, could be described as superego-oriented, these works were the exhibition’s return of the repressed: unambiguously sexual, totemic, monstrous, and grotesque. Siena distilled his affinity with the wildly imaginative work of cartoonist Basil Wolverton, seen in enamel-on-aluminum abstractions like “Pharynx Dentata” (2010), into a more straightforward point of reference in drawings and gouaches like “Semi-Flat Head” (2008), “Blind-Nose Man” (2010-2011) and “Flat Hollow Decaying Face” (2009). While you’d never confuse Siena’s work with paintings by former Hairy Who artists like Jim Nutt and Karl Wirsum, his “Screaming Old Man” (2008-2011) is a distant relative. Wacky sexuality was on display in “Member” (2009-2011), which depicted a big, curled-up, lazy-looking penis over an elaborately wrinkly scrotum; and “place, second version” (2009) was a drawing of an inviting-looking, cartoony vagina – Courbet’s “L’Origine du monde” (1866) re-imagined for our own time and place. Other images in the room were tribal in feeling, like bark paintings by Australian aborigines, though their wiggly configurations made them look like they had their skeletons removed. “Flat Red Girl” (2008) turned a prehistoric-looking body into a floppy maze, while “First Devil” (2008) and “Dick-Headed Deep Dugged Devil” (2009) were surreal in their blend of sexuality and monstrosity. These paintings related to Siena’s abstract work through their concern with obsessive imagery and perfectionist technique, but might have been separated from the paintings and prints in the front room because their explicit imagery clashed with that room’s “pure” two-dimensional abstract works of art. And, since the presence of any representation at all breaks the taboos of strict abstraction, their being in the back room of the gallery reminded one a bit of the adult section of a video store. Even though grouping similar objects is a reasonable approach to organizing an exhibition, Siena’s figurative work complements his abstractions and didn’t need to be segregated from them –it would have been just as interesting to see these transgressively representational works juxtaposed alongside the abstractions.

James Siena, Exhibition view, 2011, The Pace Gallery, New York, Photo: G.R. Christmas

When viewed as a whole, James Siena’s work suggests the possibility of never-ending variationsand the potential distractions of diverging paths. He has created a literally labyrinthine body of work that leads in unpredictable directions. By ranging from a clear, personal geometry to subversively deranged grotesquery, his artwork happily evokes many levels of perception and reality that are hidden from our unaided senses.

James Siena, The Pace Gallery, New York, March 25-April 30, 2011