IN DEFIANCE OF DEATH AS FINITUDE Jillian McManemin on “Exposé·es” at Palais de Tokyo, Paris

Gregg Bordowitz, “The Aids Crisis is still beginning,” 2019–2023, simulation

“If she was alive today, she’d be at this opening.”

Wheat-pasted windows greet us at the Palais de Tokyo for “Exposé·es,” delivering messages by the artist and activist collective fierce pussy. This piece, For the Record (2013–23), provides an emotive and radical introduction to the exhibition created with and around Élisabeth Lebovici’s seminal book Ce que le sida m’a fait. Art et activisme à la fin du XXe siècle (What AIDS did to me: Art and activism at the end of the 20th century, 2017). In her book, Lebovici does away with the divide between the material (the artifact) and the immaterial (the personal), She emphasizes the lesbian; her life is present in her writing about art. As a lesbian art writer who also weaves the personal into her work, I was eager to have the opportunity to write about this exhibition.

Flanking the entrance to the exhibition inside the museum is a banner by Gregg Bordowitz that reads, “The AIDS Crisis Is Still Beginning.” The continuous nature of the epidemic is a dispatch to take with us both when we descend the stairs to enter and ascend them to leave “Exposé·es.” It collapses time and, with brevity, addresses one of the most caustic myths of the epidemic – that it exists in historical time, that it’s not alive, not among us, that it’s stopped unfolding. In Lebovici’s writing, there is an animation that is coupled with her refusal to historicize AIDS. We are all “living in AIDS” [1] and are infused with its presence.

The survey-esque “Exposé·es” is organized into eight rooms, each given a title that thematically ties the rooms together and offers a lyrical, informative guide. The aforementioned works are in section one, “Textually Transmissible,” which also includes, as a centerpiece of sorts, Lili Reynaud-Dewar’s installation My Epidemic (Teaching Bjarne Melgaard’s Class) from 2015. Its bright blood-stained curtains display reproductions of text from various sources, including Norwegian artist Bjarne Melgaard’s seminar “Beyond Death: Viral Discontents and Contemporary Notions about AIDS.” The viewer continuously returns to and passes through this installation to access the other rooms of the exhibition. I find the echoing aspects of the piece, in teaching and reteaching, intriguing, but I have a difficult time with this work – it’s very academic and it holds too much central space as the transitional object. I found its fake blood and curtains, both evoking a hospital and a medical fetish sex dungeon, to be jejune and hokey, like the most obvious signifiers of AIDS were packaged up.

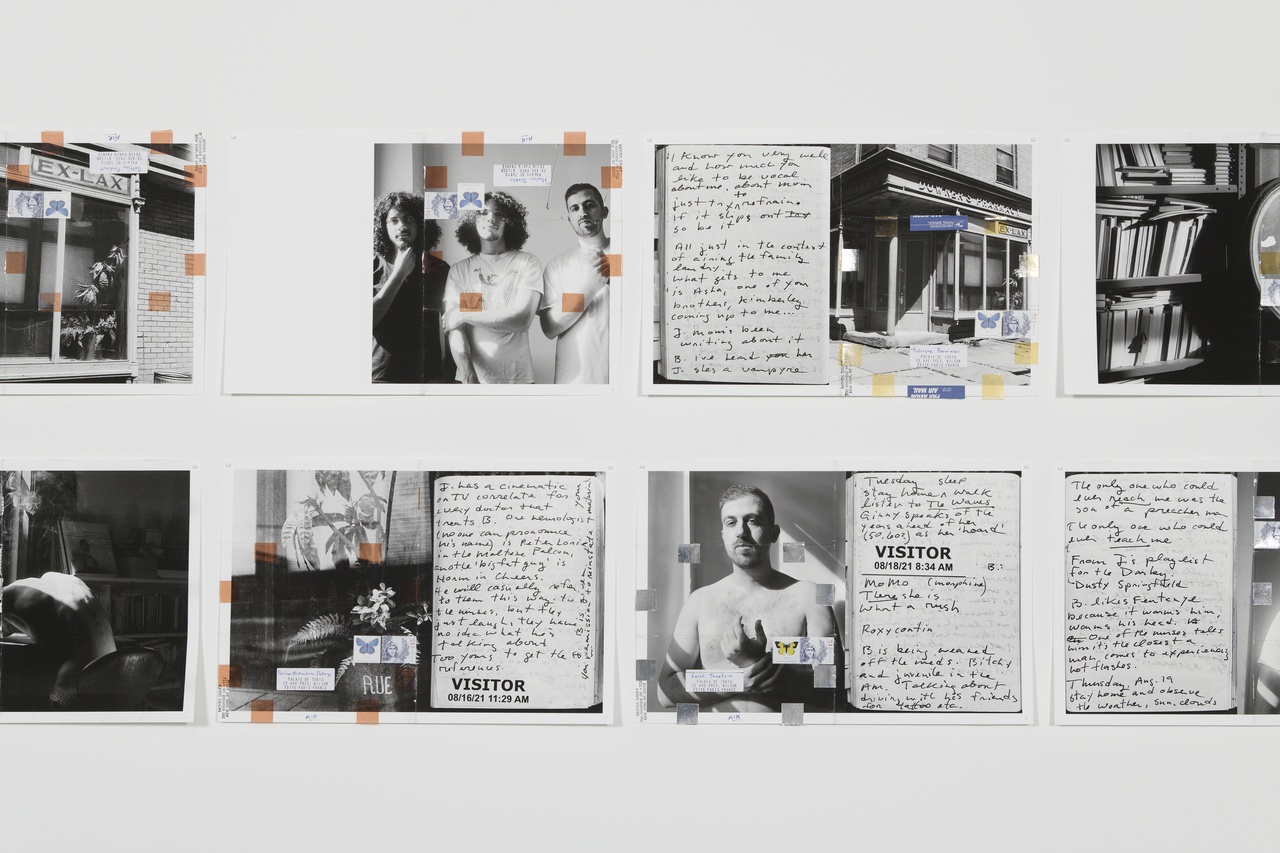

Moyra Davey, “Visitor,” 2022

I prefer Reynaud-Dewar’s libretto inspired by the argument between the writer Guillaume Dustan and Didier Lestrade, one of the founders of Act Up-Paris, on the ideas of prophylaxis and responsibility. The operatic argument recalls the infighting of activists, and specifically Act Up, which unexpectedly enabled the group’s success. Disagreements resulted in divergent actions occurring simultaneously, allowing for various levels and aspects of the struggle to be addressed all at once while also decentralizing power across the fractions and communities involved. This ethos reoccurs in the exhibition, with numerous works, modes, and movements that splinter off and rarely agree on how to address the overwhelming impact of the disease aesthetically and artistically. South African photographer Santu Mofokeng took a photojournalistic approach, emphasizing subjecthood in a region where there was intense social stigma associated with HIV/AIDS, and a very real danger of visibility. Many artists create autobiographical accounts, such as Hervé Guibert’s documentation of the effects HIV had on his body, or the work of Moyra Davey that pairs images with her journal entries and autobiographical notes, documenting her family’s struggles in dealing with the spectacularly fucked up US healthcare system. Her series of 18 photographs, entitled Visitor, were created in reference to Hervé Guibert’s images, and these two projects face each other in the exhibition.

Other artists seek to bring the viewer in: Tu, sempre (2002–23), the mesmeric installation of yann beauvais, is incredibly effective when it comes to enmeshing spectators into the changing image and text, into the convergence between the fragmentation and continuity of the epidemic – how time (and narrative) is ongoing yet constantly disrupted. The artist constructs a mirrored abstract sculptural form, a monument that spins around and around with imagery like graffiti that spells out “AIDS CURES FAGS,” which then quickly gets refracted by a strobe light to text that reads “AIDS IS NOT ABOUT DEATH. IT IS ABOUT PEOPLE LIVING WITH AIDS.” Lights flash, and the mirror brings my body into the spinning form, while the layering messages and glimmers overlay my reflection. What’s most striking about this is the hypnotic effect the installation has – how it holds you.

“Exposé·es” resists establishing an end, demarcating historical time, or establishing an authority on historical time in the present, as monuments and memorials set out to do. Instead, the exhibition presents the impact that the epidemic had on art itself – while previous generations of the avant-garde deified the functionlessness of art objects, artists dealing with the AIDS epidemic did away with this concern – art objects became an archive, a meditation on the body that ran contrary to the medical institutions and mainstream media, a way to reach out and process, to rage, and raise awareness, a means to speak, connect, and redefine living and dying.

Jesse Darling, “Reliquary (for and after Felix Gonzalez-Torres, in loving memory),” 2022

The installation by Lionel Soukaz and Stéphane Gérard goes back and forth between two films: RV, mon ami (1994), by Soukaz, and Artistes en zone troublés (2022), by Soukaz and Gérard. The films’ use of home video could easily be seen as sentimental. The medium is usually forgettable and non-specific, but here there’s a riveting quality, both sweet and anxious. The time we view the film is our time with the subject; the fleeting quality conveys that grief is imminent, which is about the epidemic but also the medium of film in general. Artistes en zone troublés was specifically created for this exhibition, the film and the exhibition both represent a practice of regurgitation, the act of reusing or reconstituting, a necromantic art that “Exposé·es” returns to in other forms, including Jesse Darling’s piece Reliquary (for and after Felix Gonzalez-Torres, in loving memory) (2022), which is composed of two light boxes filled with the remnants and fragments of González-Torres’s various installations. I feel so torn about this piece (always a good sign). I almost want to stop the artist from collecting, and thus preserving that which ought to be ephemeral, which quickly leads me to consider the role of the museum, the unease and near impossibility of letting art and material dissolve. But in the context of the exhibition, in the content of González-Torres, I think of the material fragments I’ve held on to from loved ones who passed: things that may be considered trash are elevated and become vibrant objects charged with pain and love.

“Exposé·es” “leaves behind the ostensible boundary between activism and artistic practice” [2] and, with this, engages in a complicated space of both unity and discord. But, while the individual artworks in the exhibition perforate this binary, I question the role of the curator and the role of the exhibition as inherently historical vehicles. The activist ideally includes as much as possible, while the curator sifts through, edits, and, in doing so, invariably leaves some voices out. In “Exposé·es,” there are moments where the splintering functions, and times there are too many shards. This is experimental and ambitious, but at times uneven for the viewer.

“Exposé·es” is most successful when the aesthetic relations between artworks harmonize, which isn’t necessarily even guided by contextualization, reference, or history. The strength of sense memory and aesthetic recall hardly requires explanation in the context of any exhibition, sense memory is one of the most powerful and uncontrollable effects of grief and trauma – when sight, scent, and sound come barreling back into the body via association. Pascal Lièvre’s silhouettes and wax portraits, Six Portraits a la bougie (des archives pour le futur) (1996) and the Body Maps (2002) from the Bambanani Women’s Group have a gorgeous aesthetic relationship to each other, which leaves a lot of room to hold the stories that their individual pieces represent. I spent a long time with the Bambanani Women’s Group in particular, reading autobiographical excerpts while looking at therapeutic drawings. Many of us have done similar exercises with grief and trauma counseling, but these works transcend often mind-numbing institutional therapy and become ritualistic, even magical.

“Exposé·es,” Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 2023, installation view

Zoe Leonard’s reinstallation of her intervention at the 1992 edition of Documenta, featuring close-up black-and-white photographs of her friends’ vulvas, is another magical reanimation. The photographs appear all over the exhibition. There’s a spectral quality to the reiteration, all while making visible. This piece acts as a throughline to the most harmonious room of “Exposé·es”: “arms ache avid aeon” by fierce pussy artists Carrie Yamaoka, Joy Episalla, Zoe Leonard, and Nancy Brooks Brody, an exhibition within an exhibition curated by Jo-ey Tang. The project “arms ache avid aeon,” which was previously shown in other institutions, has been conceived of in movements or chapters that include non-chronologically displayed selections of the artists’ works from the 1980s to the present. Leonard’s vulva pieces and “arms ache avid aeon” occupying such prominence in the exhibition is triumphant; lesbians have been marginalized in most narratives about HIV/AIDS and not as included in other survey shows that have focused on the epidemic.

Where other areas of the exhibition have an air of conflict, “arms ache avid aeon” is a respite – an aesthetic pause. The resonance that the works have in relation to one another enables the viewer to tune into their own body in relation to the art; it’s a much-needed subtle power and clarity of vision. There’s an embodiment in the individual practices and processes of Episalla, Leonard, Brooks Brody, and Yamaoka that is shaped by activism and is fused with the considerations of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, which is also present in their collaborative works as fierce pussy. Brody’s fragile, ghostly Cubes (2022) are a commentary on the body as well as a cheeky ribbing of sculptural theory that dealt with illusion, weight, and the sculptural core. Brody teases masculinist aspects of art historical dialogue – the skeletal cubes are positioned as a relief which in form demands sculpture to tell a linear story, which the artist gently refuses. The tactility of Yamaoka’s purple x gray redux (1997/2022), in two parts, deals with materiality and reflectivity on the boundary between photography and sculpture, and Episalla’s glorious, ruinous foldtogram (2018/2019/2020/2021/2022/2023) is a silver gelatin object, creased and fused with touch, death, and memory.

On a simple black crate is their iconic collaborative work, a stack of photocopies of AND SO ARE YOU (2018–19), a takeaway with the words, “I AM A queer…dyke AND SO ARE YOU––”; the viewer is directly addressed, an important part of the work which is intensified by taking the words with you. I’m left with a tactility from practices that emerge from an embodiment of the epidemic, of witness, anger, and desire, an active quality, which is what Élisabeth Lebovici’s book is about, an aliveness, a “living with,” and an interwoven approach to handling materiality, narrativity, subjecthood, and objecthood. Even the exhibition title, “Exposé·es,” reflects Lebovici’s politics; it’s a feminist spelling, a refusal to make the plural default to the masculine. There are so many other people and works one could talk about in “Exposé·es”: iconic artists like Barbara Hammer, David Wojnarowicz, Marion Scemama, and Derek Jarman, the innovative work of Black Audio Film Collective, and more, including other ways to see the exhibition – which is remarkably in defiance of art history, with its focusing on being, making, and reanimation. In defiance of death as finitude.

“Exposé·es,” Palais de Tokyo, Paris, February 17, 2023–May 14, 2023.

Jillian McManemin is an artist and writer based in NYC. She is the founder of the Toppled Monuments Archive and is working on her first book, Sculpture Kills.

Image credit: courtesy of Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 2–4: photo Aurélien Mole