WORLDS WITHIN WORLDS: A REASSESSMENT OF FLORINE STETTHEIMER Laura Vielmetter-Diekmann on “Florine Stettheimer: A Biography” by Barbara Bloemink

Florine Stettheimer, “Ashbury Park South,” 1920

The year 1916 proved to be a pivotal time in Florine Stettheimer’s life. Around the middle of the decade, many artists and intellectuals fled war-torn Europe to New York, where they were enthralled by the pace of urban life, and where they imported their avant-garde ideas – not that such things were new to the well-traveled Stettheimer.

1916 was also the year the artist, then in her mid-40s, presented her first solo exhibition, which has since become shrouded in myth; it is, for example, not true that the artist, out of disappointment when none of the works in that show sold, refused to exhibit again. While Barbara Bloemink devotes an entire chapter of Florine Stettheimer: A Biography to this pivotal time, her book goes far beyond it. The art historian, who wrote her PhD dissertation on Stettheimer and curated an exhibition of works by the 1871-born painter at the Katonah Museum of Art in 1992, draws on a variety of archival material and takes up the challenge of reinserting Stettheimer into the canon of modern art. The painter’s diaries, which are now assembled at the Yale Collection of American Literature, are central to the narrative, which is not without difficulty – someone, possibly the artist’s sister, cut personal information from the journals. Additionally, Stettheimer’s furniture and many of her frames have been destroyed, all of which were part of an overall conception of art (p. 17f). Bloemink adds to the story via minute descriptions of Stettheimer’s paintings and close readings of contemporary photographs.

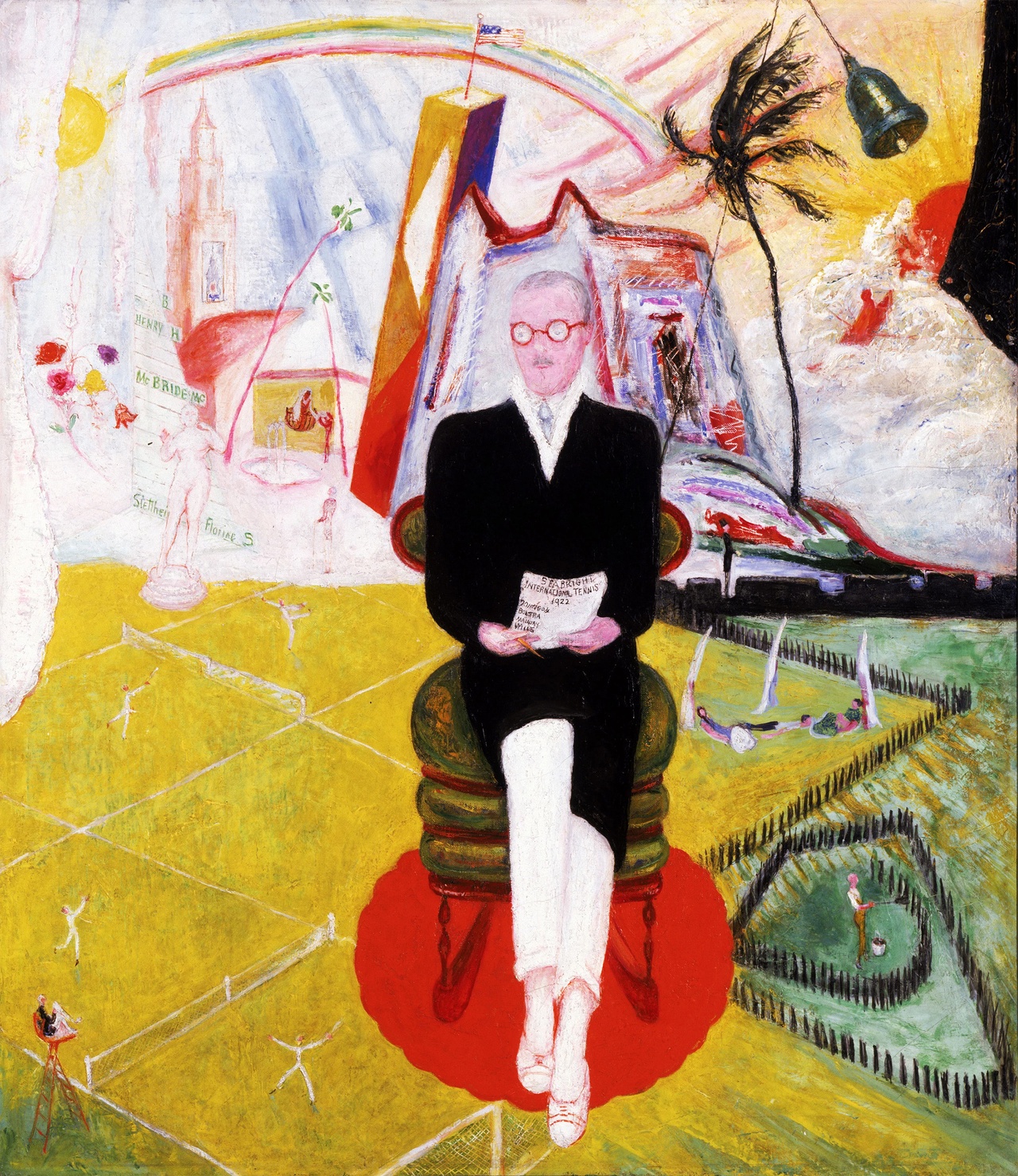

Some of the myths Bloemink seeks to dispel originate in the way critics and biographers have presented the artist posthumously. Most influential of these authors was Parker Tyler, [1] otherwise known as an early historian of underground cinema and a chronicler of Hollywood debauchery. More than 15 years after Stettheimer passed away, the family lawyer commissioned the film critic to write a biography of the artist, which was released in 1963. Tyler, notes Bloemink, stated that he embellished and exaggerated his account, thereby obfuscating a view of Stettheimer as an independent artist with clear notions about her own work. He is thus partially responsible for the myth that portrays Stettheimer as a timid, reclusive, and ultimately disappointed amateur artist (p. 12). Tyler told the story of an oddity in American art history and placed Stettheimer at the edge of the canon. Bloemink disagrees. “In fact,” she writes, “Stettheimer was an ambitious feminist, who fully understood the significance and value of her paintings and determined to be taken seriously as a professional artist” (p. 12). Save for a few authors, the critics who had followed Tyler’s account fell for his conception of the artist as an embittered eccentric, although it conflicts with the facts: Stettheimer was invited to show in numerous high-profile exhibitions, among them the first Whitney Biennial, presentations at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the Carnegie International in Pittsburgh. Bloemink condemns such overly superficial readings of Stettheimer’s biography – notable exceptions include the criticism by the artist’s friend Henry McBride.

Florine Stettheimer, “Henry McBride, Art Critic,” 1922

Regarding Stettheimer’s feminism, Bloemink develops its parameters from careful readings of the artist’s diaries. Stettheimer was born into a wealthy German-Jewish family in New York, and early in childhood, her father abandoned the family, leaving her mother with five children. The three youngest Stettheimer sisters – Ettie, Carrie, Florine – chose not to marry, which Bloemink attributes in part to their matriarchal upbringing. But Bloemink is also meticulous in her reconstruction of discourse around women’s liberation during Stettheimer’s time. The 1890s brought significant changes in terms of opportunities for women – as long as they were white and middle- to upper-class. “We find her in the salons, this New Woman […] she lives a full life, a complete and powerful one, equal in intensity and output to that of a man,” wrote the pseudonymous author duo Marius-Ary Leblond at the end of the century. [2] And in 1916, the magazine Vanity Fair wrote “marriage will have to yield to feminism in the end.” [3]

During the first 40 years of her life, Florine travelled extensively with her sisters, and her diaries are full of observations from Italy, France, and Germany. The Rococo revival in the early 20th century had a profound influence on Stettheimer, suggests Bloemink – and the drawings and illustrations she made at the time show a flowing style reminiscent of the trend. Moreover, the style’s integration of artworks and other objects must have resonated with her, and around that time she started designing her own furniture.

The Stettheimers lived in Paris before the First World War and heard the philosopher Henri Bergson lecture on the concept of durée; Florine attended the Cubist Salon d’automne, and she was impressed by the non-normative concepts of sexuality in the European metropolis (p. 76). Especially impactful to Florine’s artistic development was Sergey Pavlovich Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, which was founded in 1909 and influenced a variety of progressively minded artists. The company broke all of classical ballet’s rules, and its performances prompted Stettheimer to create her own ballet, which she conceived as a Gesamtkunstwerk, though it was never staged. She incorporated cellophane – a new material at the time – into the dancers’ costumes (and eventually into the design of her own apartment). Ultimately, her vision for a Gesamtkunstwerk materialized when, in the mid-1930s, she designed the stage sets and costumes for the opera Four Saints in Three Acts with a libretto by Gertrude Stein and a score by Virgil Thomson (p. 79).

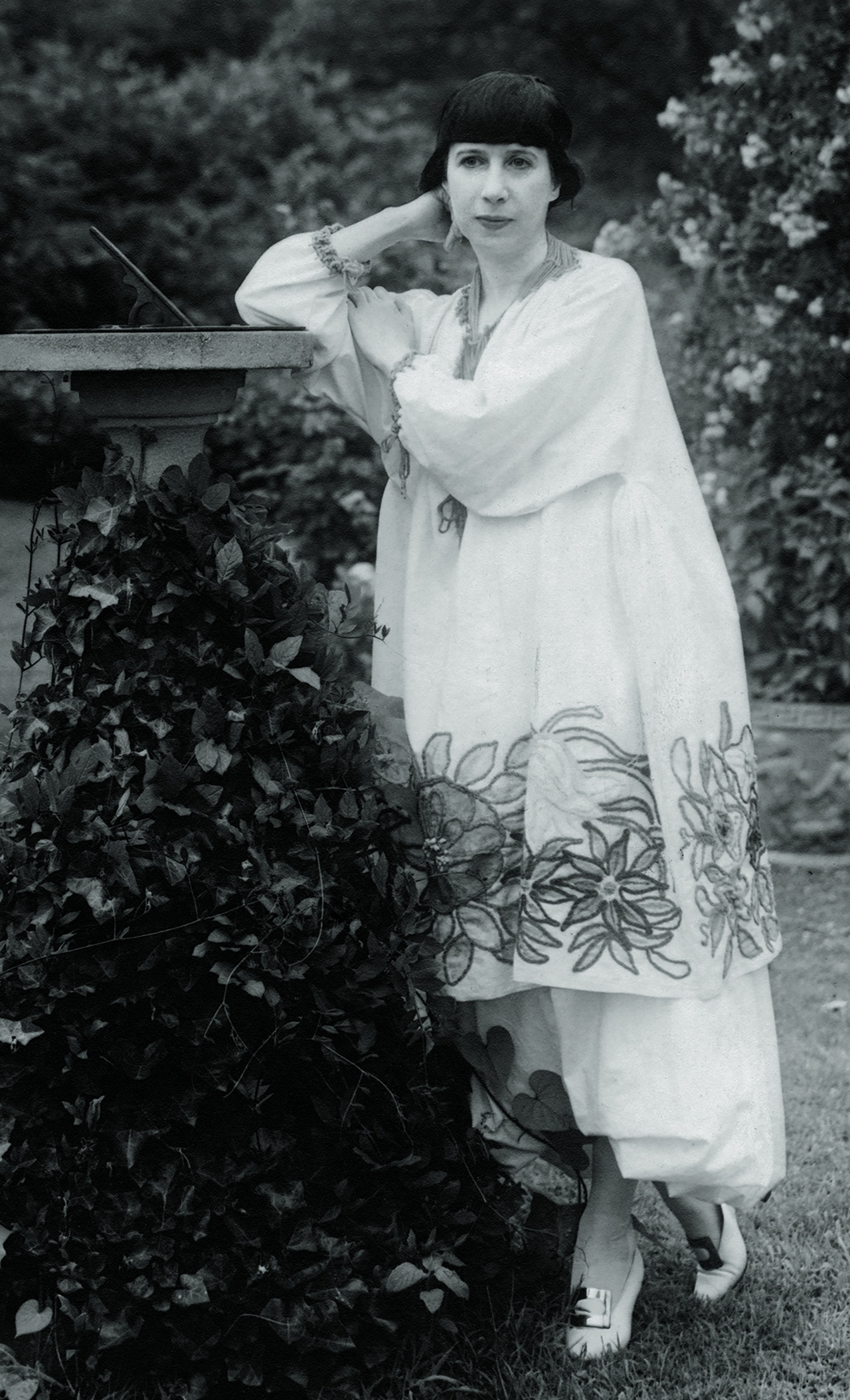

Peter A. Juley & Sons, “Photograph of Florine Stettheimer,” ca. 1917–20

The First World War made voyages between the United States and Europe increasingly difficult, leading the Stettheimers to cut short a trip to Switzerland and return to New York. Not long after, Florine established herself as salonnière, and counted exiled avant-garde provocateur Marcel Duchamp as well as the painter Georgia O’Keeffe and the critic Henry McBride among her friends. In the first few years back in the United States, Florine confidently painted herself as a nude. The painting refers back to Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1538), or Edouard Manet’s Olympia (1863), and Bloemink reads the pose and the references as an empowering gesture: the artist’s self-depiction boldly returns the viewer’s gaze.

Stettheimer’s paintings do not sit easily with the modernism of her contemporaries. Bloemink views her idiosyncratic, varied work as “continuous, unfolding, intimate, visual documentaries of an era and class” (p. 15) – as if captured by a camera. This experiential quality recalls the sensibilities of the 1960s, and the critic Adam Gopnik has recently identified Stettheimer as a precursor of Pop Art. [4] That notion is not far-fetched at all when, for instance, we look at Stettheimer’s snapshot-like Portrait of Avery Hopwood (1915), which captures the playwright in front of a billboard advertising his most recent piece, as if facing a camera.

There is an uncanny quality about Stettheimer. She was at the center of cultural life in New York, yet the narrative that presents her as unknown outsider has stuck particularly well. She was simultaneously present and absent in the art world. The obscurity in which she allegedly spent her life is only a relative one. She was wealthy and threw parties, and she had a tightly-knit group of admirers, but as a Jewish female artist, she was, as the art historian Linda Nochlin noted in 1980, simultaneously an insider and an outsider. Nochlin’s tellingly-titled essay “Rococo Subversive” contextualizes Florine Stettheimer in what the author understands to be a “Camp sensibility” [5] which sets itself apart from high culture and its morals. Nochlin, however, seeks to untangle Camp from the purely aesthetic. “Camp sensibility is,” according to Susan Sontag, “disengaged, depoliticized – or at the very least apolitical.” [6] Instead, Nochlin points to the “actively subversive component inherent to Camp,” [7] and the way it developed into a tactic against the strictures of formalism and the avant-garde. Nochlin was instrumental for a Stettheimer revival when she and Ann Sutherland Harris included her in the 1976 exhibition “Women Artists: 1550–1950.” Thanks to Nochlin’s essay, Stettheimer was introduced to a new audience, as Bloemink affirms. But “Rococo Subversive” also situated Stettheimer and her work in a new context, one that acknowledges the artist’s camp sensibility while also taking that sensibility from an aestheticized private sphere and foregrounding its social impulse. Stettheimer’s The Cathedrals of Art (1942), which is the last of her Cathedrals series, is a remarkably self-referential image of the museum microcosm. The erstwhile directors of the city’s major art institutions are shown, and critics, dealers, and Stettheimer herself gather in the crowded image. This may be a celebration of the forces of cultural establishment at the time, but Nochlin insists that this painting is also an astute critique of the art world, done by someone who is simultaneously a part of and outsider to it.

Florine Stettheimer, “The Cathedrals of Art,” 1942

Bloemink seems less interested in unearthing Stettheimer’s criticality and subversion than in reconstructing the cultural climate in which the artist lived. Viewed from today, Stettheimer’s work appears at odds with the art of many of her contemporaries: it’s dated, but also ahead of its time. Stettheimer was influenced by folk art as well as by contemporary magazine cartoons. Her style was a departure from her classical training, yet it had little in common with the formalist abstraction of the era. In fact, nearly every decade since her death has seen at least one rediscovery of her work: “What seemed out-of-touch in the 1930s – a last gasp of a bawdy, showy era only just past – becomes appealingly retro in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s,” [8] writes the art historian H. Alexander Rich about Stettheimer’s Cathedrals series, which indeed seems to be an echo of New York in the belle epoque, although the paintings were begun in 1929, after the stock market crashed and at the onset of the Great Depression. Each of Stettheimer’s Cathedrals “encloses several worlds within worlds,” says Bloemink (p. 293). The large paintings depict quintessentially modern aspects of life in New York: the movie theaters of Broadway, the luxury of Fifth Avenue, Wall Street, and the arts.

Bloemink begins her book with the end. Four years after Florine Stettheimer’s death in 1944, Joseph Solomon, the Stettheimers’ lawyer, was drifting on a motorboat in the middle of the Hudson River, where he scattered the ashes of the artist. A few years later, Solomon would commission Parker Tyler to write the first biography of Stettheimer. This is also a start – here begins a posthumous perception of the artist, which is as varied and contradictory as Stettheimer’s work itself.

Barbara Bloemink, Florine Stettheimer: A Biography, Munich: Hirmer, 2022, 432 pages.

Laura Vielmetter-Diekmann is a writer based in Berlin and a scholar with a focus on Florine Stettheimer.

Image credit: 1. Public domain, private collection; 2. Public domain, Smith College Museum of Art; 3. Florine Stettheimer Papers, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York, Gift of the Estate of Ettie Stettheimer; 4. Public domain, The Metropolitan Museum of Art;

Notes

| [1] | Parker Tyler, Florine Stettheimer: A Life in Art (New York: Farrar, Straus, 1963). |

| [2] | Quoted in Bloemink, Florine Stettheimer: A Biography, 43. |

| [3] | Quoted in Bloemink, Florine Stettheimer: A Biography, 57. |

| [4] | Adam Gopnik, “How Florine Stettheimer Captured the Luxury and Ecstasy of New York,” New Yorker, Feburary 28, 2022. |

| [5] | Linda Nochlin, “Florine Stettheimer: Rococo Subversive” [1980], in Florine Stettheimer: Manhattan Fantastica, by Elisabeth Sussman with Barbara J. Bloemink (New York: Whitney Museum of Art; Abrams, 1995), 97–116, at 101. |

| [6] | Susan Sontag, “Notes on Camp,” in Against Interpretation and Other Essays (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1966), 275–92, at 277. |

| [7] | Nochlin, “Florine Stettheimer: Rococo Subversive,” 101. |

| [8] | H Alexander Rich, “Rediscovering Florine Stettheimer (Again): The Strange Presence and Absence of a New York Art World Mainstay,” Woman’s Art Journal 32, no. 2 (Fall/Winter 2011): 24. |