Mathieu Malouf on Kim Gordon's "Girl in a Band"

Rock memoirs all tend to have the same plot: heroes begin with dreams of making it as rock stars, get a taste of the big time, go through hell, OD more than once, eventually find balance, get into yoga or martial arts, become thankful parents, and move to the suburbs. Some of these elements are what make Scar Tissue (Anthony Kiedis), Living Like a Runaway (Lita Ford), and The Dirt (Mötley Crüe) very compelling, potentially moving books. Most are trashy, tabloidistic accounts of tragic excess in a misogynistic, lawless, dying industry where the only moral barometer seems to be the spectrum of fucked-upedness needed to breed, promote, and monetize rock stardom without self-destructing completely. What we learn in the Mick Jagger biography (not written by him), for instance, is that he has a shoe fetish and had sex with Eric Clapton (Leila, we learn, is code for Jagger) and the late Brian Jones (a sexual power move to isolate Keith Richards in the band!).

As the late literary product of a sub-genre of music born from the armpit of the rapidly institutionalizing leftovers of ’60s counter-culture, punk rock memoirs almost always serve an awkward cocktail of maturity, resignation, and introspection; verbal enzymes digesting the long-gone self-destructive adolescent impulses of individuals that couldn’t really get any closer to their nihilist core and then turned the other way: yes to life and to family; yes also to working out, maybe hashtags, an active Instagram account, humility in regards to one’s status as an icon, and to a responsible, sustainable practice of rebellion (#healthgoth?), etc. A random recent example of this would be Anger is a Drug (Johnny Lyndon, rehab-themed).

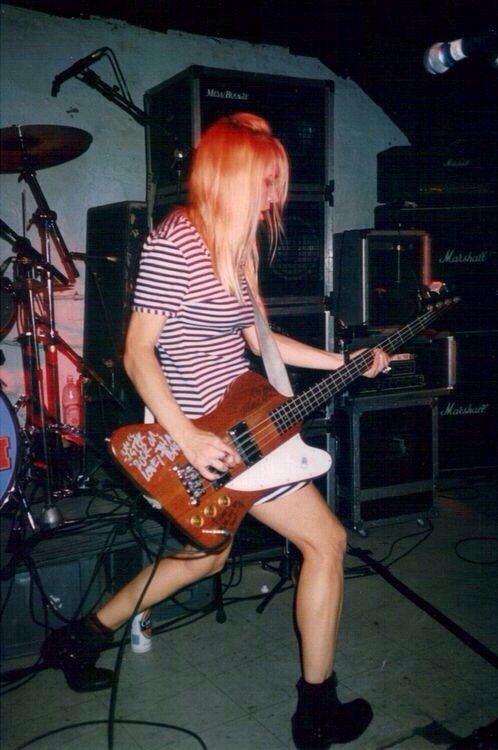

Sonic Youth, 1985

Sonic Youth, 1985

All of that barely applies to Sonic Youth, a band formed just as most of its members had managed to overcome their first Saturn return and, unlike many of the bands whose t-shirts they wore during TV interviews, were blessed with the career-planning and networking skills required to last a lifetime in rock. The end of this band (and the marriage at its core) that had managed to erase death and sacrifice from the tragic equation of punk rock and turn it into a viable, diversified brand is where Girl in Band, Kim Gordon’s reluctant rock memoir, sources the traumatic impetus that sparks its narrative into gear. Wow, who would have thought? A band whose members had managed to preserve their youthfulness way past their thirties, to wear converse shoes well into their forties, to continue to destroy their Fender guitars onstage over and over again even as their children were growing up… would be no more. After Gordon’s performance standing in for Kurt Cobain alongside the living members of Nirvana on the occasion of that band’s induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame last summer, Michael Stipe, who officiated the honor, comes up to Gordon and says that her singing “was the most punk rock thing to ever happen, or that probably will ever happen, at this event.”

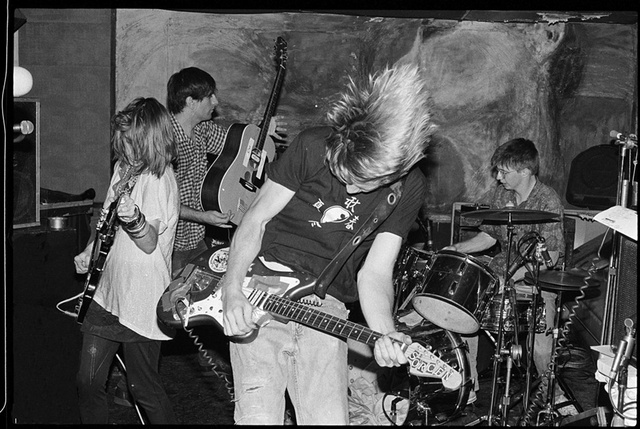

Kim Gordon and Thurston Moore. David Markey's "1991: The Year Punk Broke"

Kim Gordon and Thurston Moore. David Markey's "1991: The Year Punk Broke"

If the last rock autobiography you read happens to be the (very life-affirming) fuming heap of machismo, coagulated testosterone, and porn that is Kiedis’s Scar Tissue, it’s possible that you may find that despite the addition of ingredients such as self-awareness, intelligence, and more advanced English-language skills, Girl in a Band is very much a rock memoir. Missing only are the elements of shock value typically included to alleviate the sometimes-inevitable dullness of the ups and downs of a life in the music industry – porn, drug binges. Parallel reading of the two books reveals that Kiedis and Gordon share a lot of early musical interests and may or may not have overlapped at the Corral club in Topanga Canyon in the late ’70s when Gordon was a student at UCLA and close to John Knight while Kiedis – a 12-year-old gang-banger shooting coke and addicted to quaaludes – would wing his father (Spider, to locals, king of the Sunset Strip), hopeful to “share” in his barely legal sexual conquests.

Like Kiedis, who explains his love of nature and connection to Mother Earth by the fact that his mom has 1/8 Mohican blood, Gordon finds meaning in the lives of her ancestors too – family who went through the recession without a steady income, her own childhood in Los Angeles, and her relationship to her older brother. Gordon’s book, however departs (at least partially) from the typical rock memoir narrative in that it often takes us beyond Gordon with sections that deal with specific topics, such as music since the ’60s, returning to the art world post-Sonic Youth, Jutta Koether, and thinking about moving back to LA. Other, more conventional parts relate Gordon’s life events: memories from childhood, moving to New York in the early ’80s, and more professional, Sonic Youth related discussion including some but not too much name-dropping and celebrity gossip.

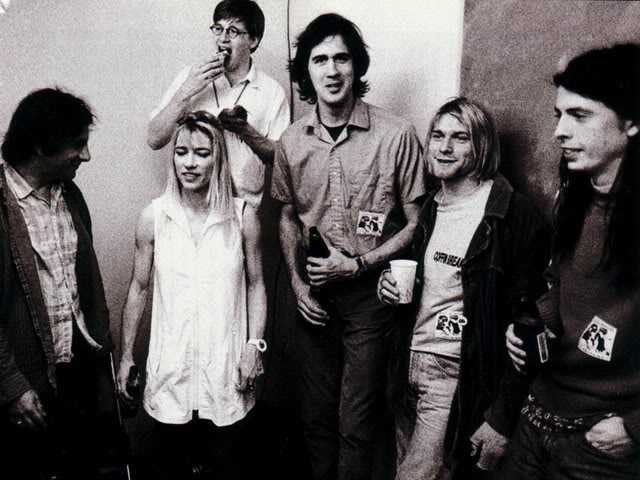

Kim Gordon and Nirvana, 1991

Kim Gordon and Nirvana, 1991

What we suspected but didn’t really know before reading this book is that Sonic Youth did not fuck groupies in the tour bus or under the drum elevator before concerts, no one did OD or go to rehab, and they did not really lose limbs in car accidents, etc. The buzzing dissonance of their signature guitar wizardry was not so much an attempt to replicate the sound of steel factories outside the window of childhood bedrooms in dodgy tenement buildings but rather, an echo of the buzzing of avant-garde artistic activity of the early ’80s New York City art scene out of which the band emerged. In a certain tradition of middle-class New York rock (The Velvet Underground, The Talking Heads, The Strokes), tragic figures (Kurt Cobain?), celebrities, art, and fashion people cross-pollinate with alluring results (contemporary New York culture is once described using the term “young girl”), all the while bringing context and contrast to the harsh, quotidian reality of life as a rock star: interviewing Yoko Ono after taking the kids to school, commuting between New York and Massachusetts. (I don’t know if it’s in a book somewhere, but Bruce Springsteen moved back to New Jersey from LA to allow his children to grow up normally and one of his sons is now a firefighter).

Although fans really won’t care that it lacks in dirt, Girl in a Band still has a little bit – Courtney Love is called a train wreck, Smashing Pumpkins’ Billy Corgan was (and still is?) regarded as a pretentious dick. We’re told how Thurston Moore starts smoking again and texting with a much younger woman, destroying his marriage; and that Gordon, just last year, made out with someone in a car parked on a hill somewhere in Echo Park but did not stay over because she had to fly back to New York to play said Nirvana Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction (the same night that Kiss, Hall and Oates, and the E Street Band, were also signed in). Where more traditional rock stars usually pepper their musings with mentor figures that nicely complement their brand and persona (for Kiedis, it could be Mother Nature, his dad, and Iggy Pop), Gordon doesn’t do much namechecking in the way of expected girls in bands (there’s no Suzi Quattro, Joan Jett, Kira Roessler, etc.). Instead, male figures – particularly ones likely familiar to readers of this magazine – hang over the narrative: John Knight, Mike Kelley, Dan Graham.

Kim Gordon and Jutta Koether, New York, 2010. Photo: Andrew Russeth

Kim Gordon and Jutta Koether, New York, 2010. Photo: Andrew Russeth

If it’s possible that the best “anti-rock memoir” – a term Gordon has used in interviews regarding her book – would have been no memoir at all, purists should note that Girl in a Band is at least not called Absolute Glittery Sonic Chaos, Death Fuck Kill Rodarte, Pussy Galore Police Death or even Get Rid of Yr Dark Star Core Sonic Death. The obvious commercial decision here on the part of the publisher would have likely been to enlist a sort of resurrected golem of late ’80s Kim Gordon – someone who wore sunglasses indoors during TV interviews and expertly generated soundbites that made the media appear uncool – to hack out a scene-driven tell-all about no-wave, grunge, the art and fashion worlds of the 1980s and ’90s – possibly stamping Lena Dunham praise on the jacket… or Dan Graham praise? Grimes praise? One need not look any further than Madonna’s Instagram and newfound enthusiasm for the word “bitch,” the semantic field of pole-dancing, and hashtags like #bitchimmadonna, #youmaykissthehand or #bitchimwearingalexanderwang to witness the awkward spectacle of a star aggressively updating their brand to current standards and clinging to past glory. Girl in a Band instead presents a less edgy, grown-up version of Kim Gordon – a rock and roll character whose biggest vices are the occasional Xanax and a good wine – unglamorous and earnest; the simple testimony of a woman who, after successfully juggling the roles of Sonic Youth front woman, fashion icon, mom, entrepreneur, and artist in her own right, is now looking to the future.

Kim Gordon, Girl in a Band (Faber & Faber, 2015); also in German, translated by Kathrin Bielfeldt und Jürgen Bürger (Kiepenheuer & Witsch, 2015)