THE STRUCTURE OF AN ERROR Matthew Rana on Lutz Bacher at Astrup Fearnley Museum, Oslo

“Lutz Bacher: Burning the Days,” Astrup Fearnley Museet, Oslo, 2025-26

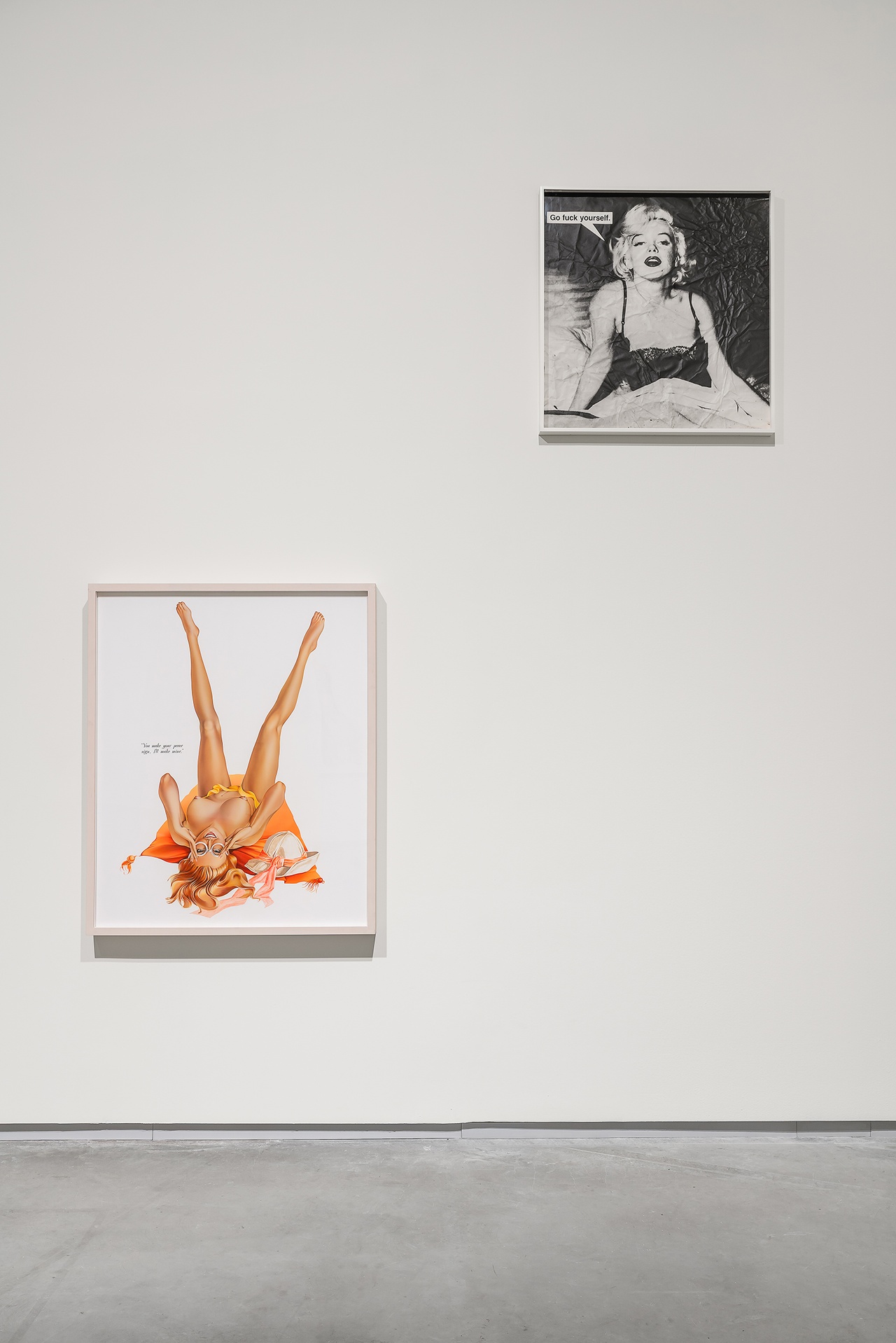

“Go fuck yourself,” reads the speech bubble in a photo of Marilyn Monroe in what is perhaps Lutz Bacher’s best-known series, Jokes (1985–88). Here, the artist photographed the pages of a found comedy book containing irreverently captioned images of American celebrities and politicians, then displayed them as large-scale framed and distressed copies. Monroe, who tragically died of a drug overdose at the age of 36, is pictured in bed wearing a black negligee, her head tilted back. There is little about the work that is funny. But if we laugh, it is because we perceive in the one-liner a double-meaning or a split: an unambiguous statement in defiance of the male gaze that also designates quite precisely the aim of male fantasy.

Such contradictions abound in Bacher’s posthumous survey, “Burning the Days,” a collaboration between Oslo’s Astrup Fearnley Museum and WIELS Centre for Contemporary Art in Brussels, where the exhibition will travel in 2026. Spanning three floors as well as the Oslo museum’s reception, terrace, and façade, this careful selection covers over four decades of the late artist’s work, from the seldom-exhibited early performance for camera Smoke (1976) to her last completed series, FIREARMS (2019). Throughout her career, Bacher scrutinized American obsessions with celebrity, sex, and violence with an unflinching gaze. Her conceptually cool handling of highly charged materials – from pornography to legal testimony – can be profoundly unsettling. Indeed, despite the impersonal nature of Bacher’s work, it still carries heavy psychological freight. Here, this is felt most keenly in the sculpture Big Boy (1992). Shown propped up against a glass railing in the mezzanine gallery, this monumental reproduction of an anatomically detailed plush doll – with a dark tuft of pubic hair and a rose tongue lolling out – of the kind used in child sexual abuse investigations (children may be asked, for example, to indicate on the doll’s body where their own body was touched, fondled, or penetrated) speaks to societal protocols structuring repression and trauma as much as it wrangles with problems of representation of the body.

“Lutz Bacher: Burning the Days,” Astrup Fearnley Museet, Oslo, 2025-26

Sexual elements return time and again in Bacher, but not always in such uncanny form. Her series Playboys (1991–93), for example, presented here in a salon-style hang with the aforementioned Jokes, comprises airbrushed enlargements of illustrator Alberto Vargas’s pinups for Playboy magazine reproduced on canvas with minimal intervention, original captions included (“Sure I’m for the feminist movement. In fact, I’m pretty good at it,” one nude remarks). While much postmodern work used similar strategies to bring into view what Rosalind Krauss called the repressed discourse of the copy, there is more at stake in Bacher’s work than exposing modernist fictions of originality and authorship – although there is that, too. Part of what distinguishes Bacher from many artists of her generation investigating similar terrain, such as Martha Rosler or Barbara Kruger, and even from younger artists like Cady Noland, is her refusal to acquiesce to the “repressive hypothesis” and its imperative to uncover hidden instances of power and violence. Film industry detritus, found objects, crude utterances: Bacher’s materials rest on the surface of culture. As much the product of individual desires as of discursive structures, the violence that works such as Playboys embody is already visible, “hidden,” as it were, in plain sight.

However, the presentation at Astrup Fearnley largely shies away from the artist’s more explicitly critical and, indeed, political works. These include series such as Sex With Strangers (1986), which appropriates imagery from illustrated porn novels by way of misogynistic captions pathologizing the women in the images, and works from the early 1990s that make use of material from the highly publicized rape trial of William Kennedy Smith, the nephew of US President John F. Kennedy. Instead, following much of the artist’s recent critical reception, “Burning the Days” frames Bacher’s “provocative and genre-defying oeuvre” as ambiguous and semantically resistant. [1] Viewers are encouraged to consider the exhibition, which takes its title from one of the artist’s unfinished book projects, in similar terms “as a draft … unfinished or unfinishable.” Dispensing with many of the narrative devices typical of museum shows (didactics, timelines, themes), the curators have opted to stage what the exhibition booklet calls “a series of associative encounters” that often, though not always, bring together works from different periods based on their formal connections. One gallery, for example, pairs Pink Out of a Corner (for Jasper Johns) 1963 (1991), a remake of an early Dan Flavin sculpture, with The Pink Body (2017), composed of fleshy wall-mounted foam sculptures that resemble the back seats of cars, both riffing on Minimal Art’s aesthetics; another links an installation of stress balls scattered on the floor with The Celestial Handbook (2011), a series of framed book pages featuring astronomy photographs.

Lutz Bacher, “Horse / Shadow,” 2010

Although this approach does much to blunt Bacher’s work, what emerges is (somewhat paradoxically) a clearer sense of genre. In this configuration, Bacher’s oeuvre comes to read as an accretion of wisecracks and visual gags, an accumulation of different forms of doubling, redoubling, and repetition of art historical and pop cultural tropes. The results are not exactly funny but are more comedic in the sense that Lacanian philosopher Alenka Zupančič develops as “continuity that constructs through discontinuity.” [2] According to Zupančič, unlike jokes that work instantaneously, comedy structures a particular length of time through a series of logical breaks and interruptions. A comedic series may start with a joke, but it never ends there; instead, it remains open and unresolved, one break leading to another, and often doubling back in the process. [3]

In the mezzanine gallery, Big Boy finds a counterpart in the small wooden figure Woodman (2015). Nearby, two distressed male mannequins embrace in Boyfriends (2006); beside them, Life Form (2018) comprises a pair of carrying cases with prosthetic arms inside. In this trio of found-object sculptures, formal links start giving way to social ones – fetishism, for instance. [4] In an adjacent gallery, two companion works, the iconic rotating sculpture Horse/Shadow and Horse Painting (both 2010) are installed opposite one another in a ham-handed display. Elsewhere, heterogenous elements stand on an oversized game board in the multimedia installation Chess (2012); these include a cardboard cutout of Elvis Presley, a plastic dromedary camel, and a replica of Marcel Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel (1913/51). The effect is like listening to a joke without end: Elvis, Duchamp, and a camel walk onto a chess board … As the narrator in Bacher’s 2016 novel Shit for Brains tellingly remarks: “that’s a problem I have, forgetting the punchline.” [5]

“Lutz Bacher: Burning the Days,” Astrup Fearnley Museet, Oslo, 2025-26

Indeed, if laughter is a release of tension, as Sigmund Freud postulated, then this presentation makes clear that Bacher preferred to hold viewers in a kind of comic suspense. Images and objects repeat – are echoed, shadowed, and remade – but never in exactly the same way. What counts here are the differences, the gaps and contradictions that come into being with every repetition. There is, more simply put, no one way to represent something. Early photographic series such as Men at War and Boat (both 1975) enact this literally through visual strategies of reframing, cropping, doubling, and so on. Such interventions do not strive to raise viewer consciousness or imbue the images with unambiguous meanings (quite the opposite, in fact). Instead, they seem to repeat only for the sake of repetition, a process akin to what Jacques Lacan identified as the dynamic of the drive.

Completed just days before the artist’s death, FIREARMS is particularly suggestive in this regard. Comprising 58 framed enlargements of pages from a manual on gun repair and maintenance, this series of images of guns, captioned by detailed descriptions of design features, production histories, and care instructions, does not expose repressed violence (in the US, if not in Norway, gun violence is a commonplace). Instead, it articulates in its serial form what is ultimately at stake each and every time we repeat: the dimension of death involved in the drive’s incessant pursuit of unconscious enjoyment.

Lutz Bacher, “FIREARMS,” 2019

If, as Zupančič argues, tragedy as a genre presents the fulfillment of a subjective destiny in a singular dramatic arc, then comedy instead shows the subject’s repeated failure to reach its logical conclusion. Comedy points to the structure of an error, a kind of symbolic short circuit in which subjectivity is contingent, not fated. Yet, by showing its fundamental lack of necessity, as in the photograph of Marilyn Monroe in Jokes, tragedy has the potential to become comedy though a play of significations. Drawing our attention to what is discontinuous, equivocal, and unresolved in Bacher, “Burning the Days” helps us grasp this radically comic dimension in her work. In doing so, it also gives us the opportunity to recognize ourselves as beings that emerge not within a tragic and therefore unchangeable narrative structure, but rather at the problematic and comically variable intersection of sense and nonsense.

“Lutz Bacher: Burning the Days,” Astrup Fearnley Museum, Oslo, September 26, 2025–January 4, 2026; WIELS Centre for Contemporary Art, Brussels, March 28–August 9, 2026.

Matthew Rana is a poet and critic living in Stockholm. His writing has appeared in Art Review, e-flux Criticism, and the Los Angeles Review of Books, among others, and he is a regular contributor to Frieze.

Images Credits: © Astrup Fearnley Museet, courtesy of the Estate of Lutz Bacher, Galerie Buchholz, Astrup Fearnley Collection, photos Christian Øen

Notes

| [1] | As Beau Rutland observes while discussing of Bacher’s 1990 video Huge Uterus, a six-hour endoscopic view of the artist’s uterus, “Is it not curious for an artist who made her insides visible (to name just one clear example) to often be repeatedly charged with, as many writers have contended, making art that is meaning-avoidant?” See Beau Rutland, “Everyday Instability: On the Notion of the Personal Within Lutz Bacher’s Curiously-Received Art,” Flash Art, October 3, 2024. |

| [2] | Alenka Zupančič, The Odd One In: On Comedy (MIT Press: 2008), 147. |

| [3] | Think, for example, of the American comedy duo Abbott and Costello’s classic routine, “Who’s on First?” |

| [4] | As author Dodie Bellamy observed, writing in another context, Bacher “makes partial-objects useful and puts them back into circulation.” See Dodie Bellamy, The Letters of Mina Harker (Semiotext(e), 1998), 186. |

| [5] | Quoted in Emily LaBarge, “When Is a Door Not a Door,” in Lutz Bacher: Burning the Days (forthcoming 2026). |