RESET, RESTORE, REBALANCE Maximiliane Leuschner on Ima-Abasi Okon at the Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven

![“Ima-Abasi Okon, Incorporeal hereditaments like Love [can] Set(s) You Free, according to Kelly, Case, Dru Hill, Kandice, LovHer, Montel and Playa with 50 - 60g of –D,)e,l,a,y,e,d1;—O,)n,s,e,t2;— ;[heart];M,)u,s,c,l,e3;[heart];—S,)o,r,e,n,e,s,s4,“ Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, 2025](/media/upload/486f65c6-32f2-48af-8577-8fb78530629f-iao_va_03_lr_t_w1280.jpg)

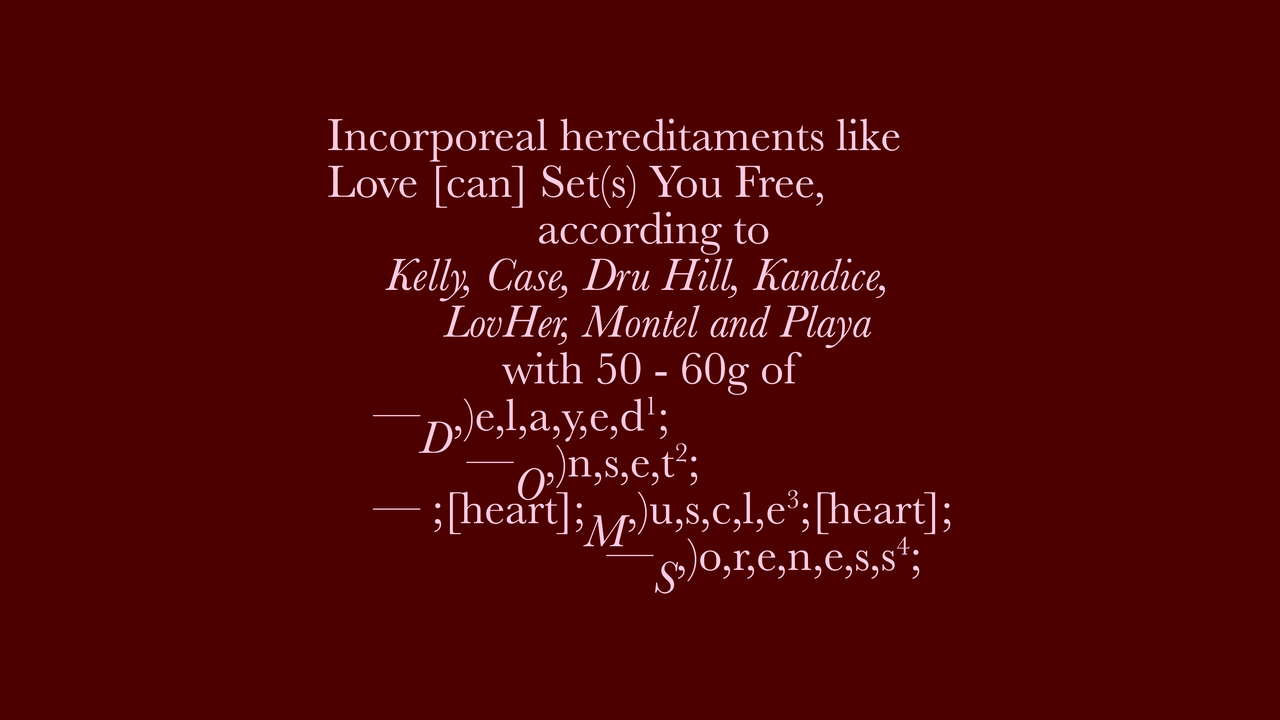

“Ima-Abasi Okon, Incorporeal hereditaments like Love [can] Set(s) You Free, according to Kelly, Case, Dru Hill, Kandice, LovHer, Montel and Playa with 50 - 60g of –D,)e,l,a,y,e,d1;—O,)n,s,e,t2;— ;[heart];M,)u,s,c,l,e3;[heart];—S,)o,r,e,n,e,s,s4,“ Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, 2025

For her current exhibition at Eindhoven’s Van Abbemuseum, Ima-Abasi Okon has turned to road running, her former lockdown habit. She draws on the historical wing’s U-shaped floorplan, which roughly resembles one half of an elliptical 400m running track. Imagine an obstacle-course-like arrangement of running paraphernalia placed sparsely across the ten symmetrical galleries: inflatable arches as doors, pressure-sensitive timing mats that, like paintings, line the walls just below eye-level, and rolled-up athletics tracks installed as sculptures. Yet this isn’t a solo show to leap through: as is typical for Okon’s exhibitions, this immersive display demands more than one lap to unfold its potential and undo the politics of competition and performance. Think an endurance run, not a sprint.

The first lap is about orientation: an inspection of the terrain, both old and new, with a cadastre-style map leading the way. By employing this form of charting, used by government officials, urban planners, surveyors, and real estate professionals to organize space according to a historical, colonial logic, Okon hints at museum founder Henri Van Abbe’s colonial past as a cigar manufacturer who sourced tobacco from Sumatra and Java, formerly part of the “Dutch East Indies,” to fund his art collection.

Entering the museum through its historical archway, we pass a vitrine window with some thirty opened exhibition catalogues showing black-and-white imagery of moody Romantic landscape paintings, selected by Okon together with the Van Abbemuseum’s librarians. Once inside, we walk over the brown, muddy-colored stone flooring, with newly placed protruding demarcation studs installed in another intervention by the artist. Walking over these studs changes our gait while traversing the otherwise empty entrance hall, making us slow down and inspect our surroundings. To our right and left, we see blue inflatable PVC arches reminiscent of marathons and other running events, in place of the usual wooden doors.

From there, we enter the exhibition galleries proper through the first inflatable blue arch. Red and blue timing mats line the walls just below our eye-level; they show signs of wear and tear, the occasional mud stain smudged across their otherwise pristine and nubby surfaces. From the exhibition text, we learn that Okon has placed 130 meters of ChronoTrack timing mats with sensors across the gallery’s internal perimeter, turning the ten galleries into one uniform enclosure, like the track in a running competition. Through the sensors, these mats keep count of how many visitors are in the exhibition at any one time. A timer installed in a different gallery further on displays the time each individual visitor spends in the exhibition, yet the count resets each time a new person enters, making it impossible for us to keep score.

Across the floor, another set of fifteen demarcation studs lead the way. This time, they pin sachets of electrolyte powder made from dried coconut water extract to the floor, as well as stacks of paper – evidence of tiresome negotiations with authorities regarding the authorization of health supplements and other (income, food, and housing-related) administrative processes involved in staging the show. Here, Okon relays what Caroline Levine labels patterns of social arrangements: forms that organize bodies in both art and political life, sculpting a landscape of care and confrontation.

On to the next gallery, where we encounter Capacitiesplural (2025), a brittle athletics track that has been rolled up and placed on four wooden pallets spread across the room. Okon has attached wearable sweat-glucose monitors to the worn and dried-out tracks, still carrying the invisible traces of sweat from the people who previously used them. A small monitor (no larger than a sheet of A4 paper) screens a moving image of swaying palm fronds, accompanied by the soothing, slowed-down R’n’B sounds of Jodice’s “Cry for You” (1993) playing from the next gallery.

Our first lap closes with an exercise: A custom-built speaker sits in the center of the space, its spinning rotors infusing the gallery’s stale air with the wholesome bacteria of a kombucha mother; it is surrounded by a lowered ceiling that hangs 70 centimeters above the ground, and reaching the speaker requires us to crawl underneath this canopy. Titled M-C-M… in a nod to Karl Marx’s law of exponential profit (money-commodity-money), this false ceiling features a flexible system [1] of mass-produced tiles that have been coated with a mixture of morphine, insulin, ultrasound gel, and gold. Through such invisible interventions, Okon applies similar strategies to her artworks and exhibitions: she transforms simple materials into artworks, exchanging their material value into an immaterial, intrinsic, spiritual one in a process Taylor Le Melle has referred to as a “spell.” [2] A selection of Mahalias (2014–25) closes this display: some twenty-three abstract portraits or “icons” (in Kazimir Malevich’s sense) of the gospel singer Mahalia Jackson, produced on mahogany-colored OSB panels – another spell transforming simple materials into a commodity.

From here, the remainder of our first walkthrough is almost identical with what we have seen before, as the exhibition follows the symmetrical layout of the Van Abbemuseum’s historical building. Okon adapted her solo show to this floorplan, using a similar mirroring or Rorschach-like arrangement: gallery 1 mirrors gallery 10; gallery 2 mirrors gallery 9; and so on. But this gives us time to breathe and meditate on what we have seen so far. We think back to previous exhibitions where we might have encountered these works in different configurations, at the Kunstverein in Hamburg, the Baltic in Gateshead, Void in Derry, or Chisenhale Gallery in London.

Having adapted to Okon’s rhythm, the second lap offers an opportunity to slow down and situate the exhibition in its broader cultural context. We don’t have to pace ourselves anymore, rather we revel in the complexities of her work; we know when to speed up, or when to slow down and linger a bit longer. There aren’t many surprises: no more sensory disruptions from the disjunct melodies and intervals, from reading through her graphically set titles, or from crawling under the lowered ceiling. Instead, we begin to meditate on the social and political criticism of her work, the moods she has set in the show. Road running doesn’t just inform the exhibition design, it’s also a gesture that holds up a mirror to the way our bodies behave in systems: what we wear, what we eat, and how we perform, or not. With this show, Okon has capitalized on her own (former) lockdown habits by turning them into art, riffing on the role of hobbies and passion projects in our quest for self-improvement: road running and fermentation have slowly entered her practice, as have sportswear brands and health supplements like adaptogens or electrolytes. These are mirrors for our use of time and energy: what health fads we spend our money on, how we fall into the trap of self-betterment. Their effect on our bodies, meanwhile, hint at the underlying political implications at play: capitalist cravings for competition, the desire to progress in life, to perform better and live healthier and longer. And in that same vein, maintain healthier bodies, optimal bodies that function like machines. Predictable, without faults. Okon situates health as the continuation of such narratives – once colonial, now capitalist – as a social pattern or logic that measures and drives our ability to perform through competition, progress, and uniformity.

These themes are also present in Okon’s other configurations, from the cadastre-style maps to the use of supplements in her work; while here they are ephemera in an exhibition, militaries use these colonial charts for issuing evacuation notices, dropped from the sky in form of leaflets, and withhold the delivery of such supplements from starving populations who need them. By interspersing her exhibition title with punctuation marks, Okon also hints at the legal terminology bound up with colonialism and its ongoing legacies in how access to land and materials is regulated. Yet the way she articulates this unequal power structure within her show remains rather oblique: her smattering of talismanic objects in psychic ecosystems provides few clues as to their origins or the actual institutional critique enacted by the artist behind the scenes, such as lengthy loan agreements aimed at slowing down institutional processes in the name of care and confrontation. Visitors thus remain unaware of such legal and administrative processes while regaling in ostensible social critiques delivered via a range of consumer products.

And so, as we approach the finish line, the impression left is an ambivalent one. A recognition of Okon’s talent in her adopted home of the Netherlands, the exhibition showcases the London and Amsterdam-based artist’s virtuosic versatility in moving between different exhibition genres with ease: whether presented alone or in an arrangement, the singular messages of her artworks remain intact, as do their reconfigurations in different contexts. Okon’s intimations question how to represent a body in its absence. Through the use of sound, scale, and light, she makes visible and audible the different forms of excess or surplus involved in the generation of value. Her installations are not idle exercises for the mind but dogged attempts to change audiences and the larger ecosystem they inhabit. To reset, restore and rebalance them, Okon practices slowness as an act of resistance. Yet her installations both compel and frustrate contemplation: she withholds our access to them by complicating the production of knowledge, and by collapsing any form of readability in either words or sounds. Ultimately, this strategy of withholding fails to dismantle the outdated structures of oppression and exploitation at play. By denying us access to the invisible gestures of her artistic practice, she perpetuates unequal distributions of power that confront but largely fail to contextualize and acknowledge.

The Van Abbemuseum takes a multi-sensorial and multiperspectival approach to accessibility initiated by its former director, Charles Esche, including a range of technologically augmented multi-sensory experiences accompanying its decolonial “Delinking and Relinking” presentation of the museum collection. Okon’s specific form of withholding situates her on the other end of this accessibility spectrum. With its deliberately obscure wall labels and supporting information, her work complicates more than it clarifies. As such, it remains for the initiated few, rather than the entire museum audience. To achieve the systemic change she desires, perhaps a pivot to more inclusive formulations might pave the way for an institutional critique whose claims are accessible to a broader audience.

“Ima-Abasi Okon: Incorporeal hereditaments like Love [can] Set(s) You Free, according to Kelly, Case, Dru Hill, Kandice, LovHer, Montel and Playa with 50 - 60g of –D,)e,l,a,y,e,d1;—O,)n,s,e,t2;— ;[heart];M,)u,s,c,l,e3;[heart];—S,)o,r,e,n,e,s,s4,” Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, May 10–September 21, 2025.

Maximiliane Leuschner is an art historian and writer based in London.

Image credit: 1. © Ima-Abasi Okon, courtesy of the artist, photo Peter Cox; 2. Graphic by Studio Lennarts & De Bruijn, courtesy of Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven

Notes

| [1] | Following Tate’s acquisition of M-C-M, the gallery’s installation conservator Libby Ireland shone a light on the institutional complexities behind the scenes that remain hidden from the museumgoers: from conservation to display, by way of instructions, loan agreements, and other burdens. For example, the gallery acquired a set number of tiles, with the instruction to cut a percentage of these during each future display. As such, the number of tiles declines with each presentation, while the title gets longer (too long for any collection management system). See: Libby Ireland, “Learning through the Acquisition and Display of Works by Ima-Abasi Okon: Enacting Radical Hospitality through Deliberate Slowness,” Tate Papers, no. 35 (2022–23). |

| [2] | “Ima-Abasi Okon in Conversation with Taylor Le Melle,” CURA, no. 33 (2020). |