Misuse of Military Equipment Jakob Schillinger on “New Order: Art and Technology in the Twenty-First Century” at the Museum of Modern Art, New York

“New Order: Art and Technology in the Twenty-First Century,” Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2019, installation view

In the early 2010s, a generation of artists emerged to the siren call of speculative realism, and the general euphoria around digitization, with 3D-animated videos and installations, often made from synthetic materials and in highly saturated colors, that promised to open our eyes to a technological future that had just arrived. Entering “New Order: Art and Technology in the Twenty-First Century,” one could expect just another survey, or – given MoMA’s stature and the fact that all works are drawn from its holdings – an attempt at canonization of this crucial moment as the decade in question nears its endpoint. Indeed, the exhibition does present works by some of its key exponents: Ian Cheng, Josh Kline, Sondra Perry, Tabor Robak, Jacolby Satterwhite, and Anicka Yi. Others, however, such as Ed Atkins and Simon Denny, are notably absent, despite the fact that MoMA’s collection includes several works by both artists. Instead, works by this cohort are contextualized with select pieces made over the past two decades by artists from previous generations, ranging from Seth Price and Wade Guyton to Leslie Thornton and Harun Farocki, and even all the way back to Louise Bourgeois. As one makes one’s way through the exhibition, it soon becomes clear that curator Michelle Kuo’s ambition goes far beyond a generational survey or the canonization of a “movement,” to borrow a now somewhat anachronistic term. “New Order” conducts a fundamental inquiry into the very relationship between art and technology in the present age.

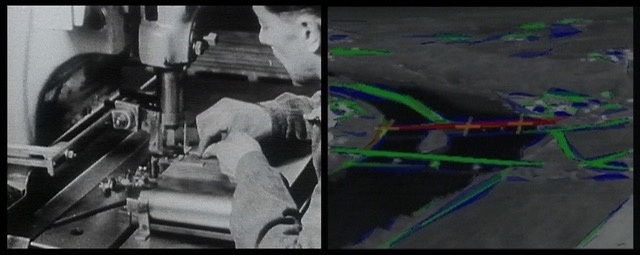

The exhibition offers two categories for conceptualizing this relationship, which are highly productive, even if their allocation to the show’s two galleries seems a bit too rigid, with inevitable overlaps. One could think of the categories as vectors. The first, “Reverse Engineering,” pertains to works that reflect on technologies and their social or biological effects on human bodies, unearthing genealogies and revealing material conditions in a broadly narrative, sometimes documentary register. Josh Kline’s Skittles (2014), for example, literalizes the way in which our technologies and their (waste) products infiltrate and affect our own bodies, whether by voluntary ingestion or through the circuits of water and produce we necessarily intercept. The light box-encased commercial grade refrigerator greeting visitors at the entrance displays smoothies whose perfectly illuminated bottles list and show ingredients such as latex gloves, Ritalin, and shredded Google Glass devices – almost forgotten today, but a hot topic when the sculpture was made. The reverse operation – the extraction of data from bodies – receives more nuanced treatment. Works by Sondra Perry, Josephine Pryde, Harun Farocki, and Trevor Paglen take up this recurrent theme, the analytical framework shifting from race to gender to class – or war. Indeed, the military genealogy of much technology looms large. Farocki’s seminal video Eye/Machine I (2001) traces the migration of image technologies from the battlefield into the factory and civilian life. It describes a technological image, read not by humans but by machines that regulate flows. Paglen’s series of inkjet prints, titled It Began as a Military Experiment (2017), presents portraits of military employees with letters marking the corners of eyes, noses, and lips – documents of early attempts at training facial recognition algorithms, conducted by the US Army in the 1990s. Pryde’s inkjet print from the series It’s Not My Body (2011) superimposes a tinted photograph of a desert with an MRI scan of a human womb containing an embryo. Presenting an alien-looking figure in a dreamlike landscape, the work raises questions regarding the role of imaging technologies in political struggles over bodies, self-determination, and what finally constitutes a self.

Seth Price, “Vintage Bomber,” 2006

While placed in the first gallery, Pryde’s work resonates strongly with the second theme, “Stranger Things.” Broadly speaking, it groups together works that appropriate – and sometimes interfere with – specialized processing technologies and fabrication procedures, diverting them from their intended use in order to discover their poetic potential. In light of Farocki’s and Paglen’s work, one is tempted to paraphrase a notion famously taken up by media theorist Friedrich Kittler and dub this section “art as a misuse of military equipment.” Sam Lewitt’s Weak Local Lineament (Copperhead 08) (2014), for example, adapts a photolithographic technique commonly utilized in the production of circuit boards to etch not signal traces but a snakeskin onto the support of copper-clad plastic. The artist’s materialist critique here pushes beyond revealing the hidden infrastructure of electronic transmission, into an aestheticization of the material and its manufacturing process. The motif of the copperhead snake therefore makes for more than a simple pun. By metaphorically folding the material back onto the level of content, it turns the work into an emblem of an artistic paradigm, in which commercial materials and manufacturing processes make up the substantive matter of art. This post-Conceptual extension of the readymade procedure from product to fabrication process is epitomized by one of its most prominent exponents, Wade Guyton, whose untitled digital print on plywood from 2009 is also included in the show. The “reverse engineering” of underlying technologies on the one hand, and their appropriation for engineering “stranger things” on the other, constitute two opposite yet complimentary vectors of artistic operations. Both imply and affirm the critical distance from technology signified by the conjunction that, in relating “art and technology,” then also sets them apart.

Digitization has affected art not only by way of production methods, but arguably even more so through shifting infrastructures of distribution and reception. The impact of handheld networked devices and image-sharing platforms on how – and by extension what kind of – art is viewed, promoted, and collected has been much discussed over the past decade. Entire genres like the dance exhibition or the aesthetics of so-called “Zombie formalism,” for example, have been convincingly ascribed to this media-technological shift. If today exhibitions often seem to function primarily as photo opportunities (Instagram fodder), “New Order” both reflects on and subtly resists this development. Part of Perry’s Graft and Ash for a Three Monitor Workstation (2016), a coat of chroma key blue paint on one of the first gallery’s long walls, invokes the eponymous blue screen technology for isolating objects from their actual site in photographic representations. In the context of Perry’s work, the blue screen becomes a symbol of the abstraction and appropriation of black bodies – and not only their images – in Western culture: from their commodification as enslaved people to complicated systems coercing college athletes to surrender their stats and data for basketball video games without compensation. But the blue coating also marks the museum as no longer simply a site of reception, but a relay – a site for the production of images that abstract iconic works from their context and pass them on via social media. This extended reading of Perry’s blue wall is encouraged by a subtle curatorial intervention in the second gallery, whose two side walls are painted black. A common means for enhancing the luminosity of moving image works, which predominate in this space, the black background has a very different effect on Guyton’s untitled black print. While it adds further layers to the rich phenomenological experience of the various nuances of blackness that characterizes the work, Untitled now all but disappears when photographed. This resistance to photographic transmission is compensated for somewhat by Seth Price’s iconic vacuum-formed panel Vintage Bomber (2006). Casting an MA-1 flight jacket in golden polyvinyl chloride, this monument to one of the most iconic and overdetermined pieces of clothing reminds us that cycles of appropriation, de-, and recontextualization have long been driving fashion, subcultures, and art. By literally turning the object into an image and imprinting it “2006,” the work points to the ways in which imaging technologies transform these dynamics. While the massive date stamp indicates that Vintage Bomber pre-dates both Instagram and the iPhone, it nevertheless clearly situates the work in the epoch of digital networks, which has since fragmented both contexts and temporal horizons to such an extent that one can hardly speak anymore of cycles, distinct movements, or styles.

Harun Farocki, “Eye/Machine I,” 2001

If, in light of such transformations, art has lately been described as a mere symptom of technology, “New Order” develops a more nuanced perspective. It presents art as a space for reflection, including the critique of technological developments and their social effects, while also registering their impact on art itself. The exhibition’s argument doesn’t stop here, however. In a footnote of sorts, “New Order” presents objects by the Mediated Matter Group around Neri Oxman, an associate professor of Media Arts and Sciences at MIT. Oxman has made a name for herself by devising digitally guided manufacturing processes that translate the functional characteristics of biological organisms into building materials or wearables – think houses that sweat when it gets hot. Among the works on view are several vase-shaped objects collectively titled Glass I (2015). They were produced with a 3D printer for optically transparent glass developed by Oxman’s group in collaboration with Mechanical Engineering and other departments at MIT, capable of outputting complete architectural components. Marked off from the rest of the show in a small vitrine, like artifacts from a different time and culture in an anthropological museum, these objects gesture toward a different relationship between art and technology: to art as neither merely symptomatic of technological developments nor a reflection of those developments from a critical distance. Rather, art here is proposed as a practice that merges with technology, into a vanguard of engineering.

“New Order: Art and Technology in the Twenty-First Century,” Museum of Modern Art, New York, March 17–June 15, 2019.

Jakob Schillinger is an arthistorian living in Berlin. He is currently a PhD candidate at Princeton University, where he works on post-conceptual painting in Germany in the 1980s.