“NOW THERE’S A REAL WORLD BREATHING” Nicole-Ann Lobo on Rashid Johnson at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

“Rashid Johnson: A Poem for Deep Thinkers,” Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2025-26

What forms of culture made this world we have inherited? The question is one of several animating American multimedia artist Rashid Johnson’s practice. Johnson, whose works are on display at the Guggenheim in a mid-career survey titled “A Poem for Deep Thinkers,” has filled nearly the entire museum with paintings, sculptural installations, assemblages, and videos – a fine display of his ability to work across mediums. He contends with questions of inheritance and how signs of Black iconicity are transmitted and received, and how they shape individual lives (more precisely, his own). The show, however, left me with a very different question: How does an exhibition filled with 95 works end up feeling so empty?

“A Poem for Deep Thinkers” takes the name of a 1977 Amiri Baraka poem, which critiques lofty intellectuals “blinded by sun, and their own images of things, rather than things as they actually are.” [1] This reminder to apprehend the world as it really is remained with me as I waded through Johnson’s seemingly endless stream of works drawing upon any number of signs and referents as they perambulate what was historically regarded as “Black aesthetic.” Johnson, a child of the 1970s, came of age in an era of Black culture wed to political movements at home and abroad, and with them, promises of liberation. Figures of that particular moment recur, guiding – or maybe haunting – the exhibition: Fela Kuti, Angela Davis, Eldridge Cleaver, and, of course, Baraka. Intertextuality is key to Johnson’s work; his practice is intensely citational, opening dialogues with a host of works, texts, and canonical figures, such as Chinua Achebe, Charles Mingus (in particular, his 1957 jazz album The Clown), and Roy DeCarava and Langston Hughes’s 1955 collaboration The Sweet Flypaper of Life. Johnson responds to Black conceptual artists of a previous generation as well, such as David Hammons and Senga Nengudi, putting his own lexicon and referents in dialogue with their playful irreverence. Motifs (in abundance) recur: the role of Black literature, shea butter, yoga, woodworking, plants. Then there are questions about iconicity and intergenerationality, as well as the artist’s visual interest in non-painterly forms of inscription and textural diversity.

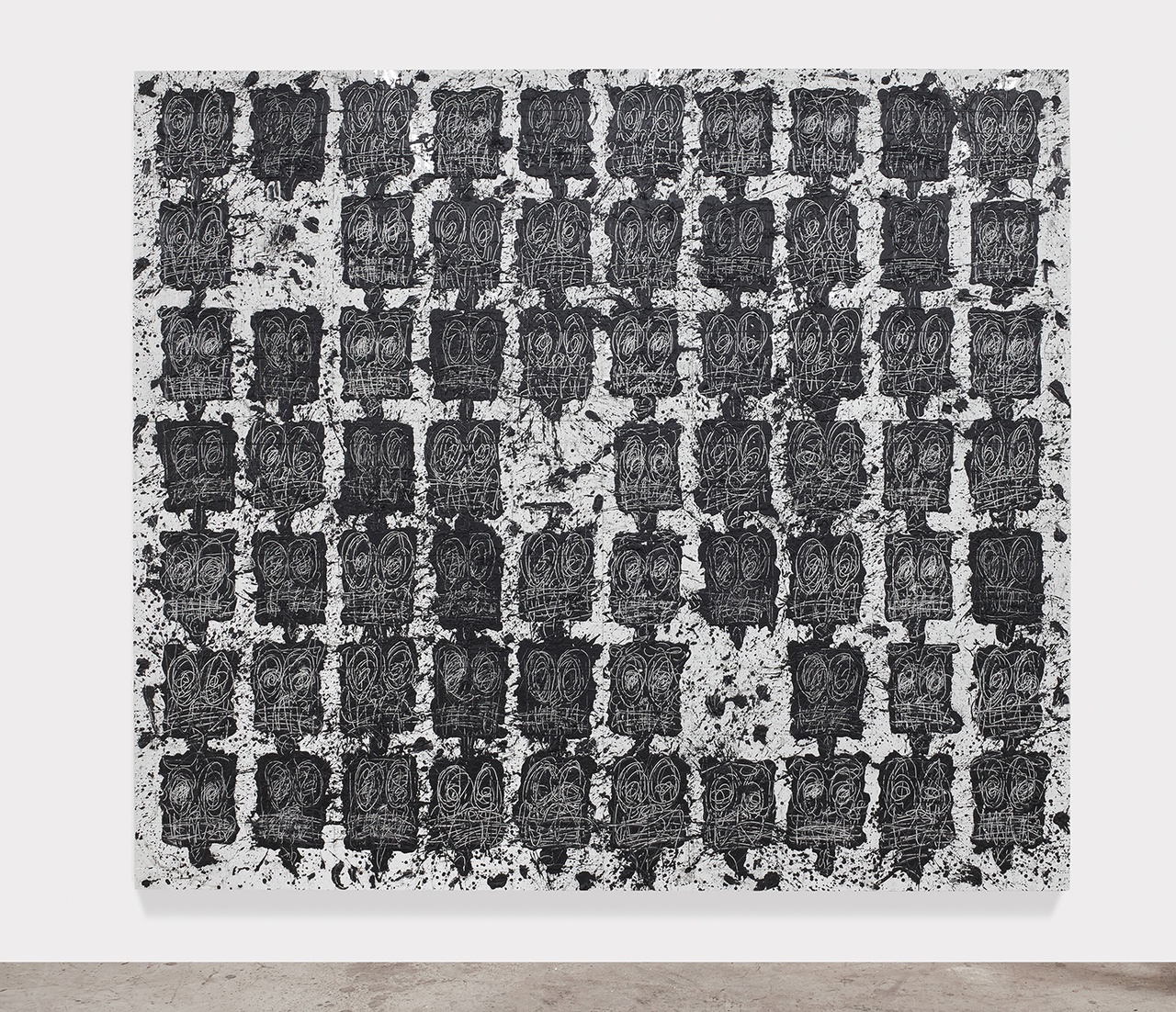

Rashid Johnson, “Untitled Anxious Audience,” 2019

If this all sounds like a lot, it is. Johnson is to be lauded, at least, for such a wide-ranging set of referents, which, at best, assemble a pantheon of revolutionary Black culture. But the tone of his constellation is far from exultatory. A sense of irony permeates the show, evinced by the fact that these referents are described in wall text as coming predominantly from the 1960s to the 1990s, “periods of his parents’ activism,” in order not just to contemplate why they “failed” but to apprehend how individual lives are carved by the legacy of his parents’ generation and the referents that molded them. Johnson’s process seems to center such intimate physicality – of what it means to mark and be marked, how one carves a path while allowing oneself to be shaped by the points of contact along the way. For instance, in Untitled Anxious Audience, the 2019 work that opens this show, Johnson has excised 70 rough facial intimations from dried wax on ceramic tile. Like many of the works to follow, this one prioritizes materials that both hold weighty significance for African American identity and evoke bodily molding as inherent to their nature: here, black soap and wax, which have been carved out via negative relief in a process Johnson describes as “drawing through erasure.”

The works that privilege rough and imprecise forms of mark-making present as some of the show’s most interesting: In Cosmic Slop “Black Orpheus,” for instance, a 2011 work of black soap and wax on wood panel, Johnson has incised an array of richly textured gashes while textured swipes appear like sutured wounds; protrusions of dripped wax additively alter the surface – a playful give-and-take in which what is added and what subtracted remains difficult to discern.

In other works, this approach to gestural wounding combines with found or owned objects to evince a totality of experience. The Sweet Flypaper, a 2012 mixed-media mirrored assemblage with shelves, vessels of shea butter, and an album cover of The Clown alongside a copy of The Sweet Flypaper of Life, has also been marked up with black soap and smeared wax. At several points, the mirrored panes appear punctured and broken. Not only do viewers imagine the sonic and haptic experience of physical encounter in interfacing with this work, but our own bodies are also literally reflected back to us, at points distorted or partially concealed by brown excrement-esque swathes, but present and immersed nonetheless.

“Rashid Johnson: A Poem for Deep Thinkers,” Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2025-26

The context that suffuses Johnson’s work is, above all, autobiographical—presented if nothing else as a disclaimer. The artist makes no pretense about evoking any universal experience, let alone one determined by racial lines – such pitfalls of essentialist thinking, he seems to say, didn’t exactly serve those who preceded him. In Self-Portrait with My Hair Parted Like Frederick Douglass (2003), Johnson solemnly gazes at the camera, evoking the manner of the most-photographed man of the 19th century. Though there’s a performative humor to the gesture, the earnestness of this early work brings with it a type of tenderness.

The tone shift, then, couldn’t be starker with the series of framed mirrors and canvases interspersed throughout, spray-painted with phrases like “RUN,” “DEATH,” and “PROMISED LAND.” The effect such works had, dull and hackneyed, with an aesthetic of graffitied self-seriousness that in turn felt kitschy beyond repair, gave me whiplash. Then, there were the shea butter incidents: blocks and fragments of the natural material positioned variously, most prominently on Untitled (Shea Butter Table), a 2016 work that featured the aforementioned material simply lying on a dirtied Persian rug, then laid onto a branded walnut wooden table. The material here, no doubt, holds important cultural and spiritual significance for many from the African continent and Black diaspora, but Johnson says he’s more interested in how it plays into a “theater of Africanism” for African American identity, similarly found in “dashikis and hairstyles and music.” [2]

“Rashid Johnson: A Poem for Deep Thinkers,” Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2025-26

One risks reading too much further into the recurrent presence of Persian rugs in Johnson’s work, for fear of too literally connecting them to the culture of the artist’s Iranian-born wife. My own anxiety around such associations may be rooted in my fundamental problem with the show: Despite the dizzying array of references, it is almost impossible to latch on to any takeaway other than how they may nebulously fit into the contours of Johnson’s own abstracted life encounters, here shinily packaged and stripped of any meaningful signification. In her catalogue essay, the exhibition’s curator, Naomi Beckwith, cites Johnson: “The subject of my work is freedom,” he argues, and in reply, Beckwith notes that “the instrumentalization of Black artists’ work toward the purpose of freedom rarely ends well.” [3]

As one continues through the exhibition, the same motifs circulate and are remixed: those same frenzied faces from Untitled Anxious Audience, arranged in a grid; more painted mirrors; darkly branded furniture; shelves bearing new configurations of vinyl covers, books, and plants. Black literature is perhaps the most salient of recurrent tropes, such that a small reading room is tucked off of the Guggenheim’s ramp, offering visitors a moment of retreat. Just outside this room is Contemporary Black Male Literature Starter Kit (2003), a work in which the artist has bundled a heap of books in plastic wrap, where they lie amalgamated on a wooden pallet. Only a few titles are visible, among them John Reed’s Adventures of a Young Man, Debra Dickerson’s The End of Blackness, and a collection of poems by Baraka (from when he was known as LeRoi Jones). The vast majority remain bundled and invisible, their contents left to the viewer’s imagination.

“Rashid Johnson: A Poem for Deep Thinkers,” Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2025-26

Beckwith argues that Johnson is responding to not just the commodification of revolutionary aesthetics, but also the weaponization of these aesthetics against the very communities whom they once intended to liberate. But this framing of Johnson’s practice – which resounded throughout the exhibition – gave me pause. It takes the failure of radical political ideals as not only historically objective but also inevitable, and any consumption of their contemporary possibility as wed to wistful idealism. If Johnson is interested in the forms of culture that led to our world as we know it, he neglects to consider why such ideals failed, how arts institutions have been complicit, and how answers of “refusal” are, rather than outsmarting the game, playing into its very tendencies: to depoliticize and confound, and to relegate freedom to the personal realm (even while such victories remain far from unimportant).

Johnson evades his work of specificity and refuses to be politicized for fear of being instrumentalized – but just who is doing that instrumentalization? And further, who exactly does refusing to be politicized in the first place serve? I was struck by the sense that for all the literary forms on display, just what these brilliant theoreticians, activists, and scholars were saying is altogether neglected. Divorced from any content beyond what they represent, they become little other than empty signifiers in Johnson’s pantheon of signs. When I spied works by Frantz Fanon aesthetically displayed on several shelves throughout the exhibition, it evoked his 1952 reminder to colonized intellectuals: Rediscoveries of Black culture sundered from politics may be “of enormous interest,” he concedes, but “we can absolutely not see how this fact would change the lives of eight-year-old kids working in the cane fields of Martinique or Guadeloupe.” [4]

The problem with Johnson’s deployment of historical figures like Cleaver and Davis is that they were not just icons: Their victories were material, and did lead to forms of liberation, even if incomplete. And for a show that purports to be about the world we have inherited, Johnson seems to have very little to say about where we are now. Little other than, perhaps, a spray-painted mirror that reads “BLACKNESS IS DEATH,” not devoid of truth, but wholly uninspiring in an era that requires militant optimism and organization in the face of pessimistic politics, a period that does not just encourage us to turn outside of ourselves but in fact demands it.

Rashid Johnson, “Sanguine,” 2025

“What’s happening is life itself ‘onward & upward,’” Baraka reminds us in that earlier poem. [5] If Johnson is weighed down by the failures that preceded him, he takes solace in a practice of cultivation, specifically of family and plants. By the end of the show, there is a tonal shift toward privatized rejuvenation. The Guggenheim, as it cascades heavenward, is sensorially heightened by plants suspended from the ceiling, dangling in midair. At the top, shelves bearing glossy ceramic pots hold various varieties of plants. The air is, quite literally, fresher up here. The final display is Sanguine (2024), a sanctuary enclosed by greenery and grow lights, with a video component showing three generations of Johnson’s family spending a day together. The tenderness of those strong early works returns. Johnson, his father, and his son apply sunscreen to each other’s backs and walk in tandem on a sandy beach before entering a stylish home, where they cook and read together, receding into the realm of care, self-preservation, and mutual flourishing. For them, life, onward and upward, continues on.

“Rashid Johnson: A Poem for Deep Thinkers,” Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, April 18, 2025–January 19, 2026.

Title: Fragment from Amiri Baraka’s “A Poem for Deep Thinkers” (1977)

Nicole-Ann Lobo is a PhD candidate in the Department of Art and Archaeology and the Interdisciplinary Doctoral Program in the Humanities at Princeton University. She also serves as assistant editor at Third Text.

Image credits: 1., 3.- 5. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, photos David Heald; 2. © Rashid Johnson / Collection of Clara wu Tsai; 6. © Rashid Johnson

Notes

| [1] | Amiri Baraka, “A Poem for Deep Thinkers” [1977], in The LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka Reader, ed. William J. Harris (Basic Books, 1999), 260–61. |

| [2] | Rashid Johnson, “The Accumulation of Self: How Rashid Johnson’s Art Adds Up,” interview by Maxwell Williams, Art in America, October 8, 2014. |

| [3] | Naomi Beckwith, “A (w)Hole in the Shape of Me,” in Rashid Johnson: A Poem for Deep Thinkers, ed. Naomi Beckwith and Andrea Karnes (Guggenheim, 2025), 73. |

| [4] | Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, trans. Richard Philcox (Grove Press, 2008), 205. |

| [5] | Baraka, “A Poem for Deep Thinkers,” 260–61. |