BREAKTHROUGH TO THE GROUND OF THE PLANETARY SOUL Nikolay Smirnov on “Planetarische Bauern” at Kunstmuseum Moritzburg, Halle (Saale)

“Planetarische Bauern. Landwirtschaft, Kunst, Revolution,” Kunstmuseum Moritzburg, Halle (Saale), 2025

The Werkleitz society and its biennial were founded by 27 enthusiasts of new media art in 1993 in the village of Werkleitz in Saxony-Anhalt. One of these founders, Peter Zorn, invoked Marshall McLuhan’s catchphrase “global village” to denote Werkleitz – “the world’s first village with internet access.” [1] A decade later, the biennial was dubbed a “documenta of the East,” likely to acknowledge its cutting‑edge practice in a relatively provincial setting. [2] Werkleitz moved to Halle (Saale) in 2003 and, under artistic director Daniel Herrmann, became an annual festival in 2008. Recent editions, cocurated by Herrmann and Alexander Klose, have focused on extractivism and food production in Mansfeld-Südharz, a nearby region with mining and agrarian history that has faced structural crisis since German unification.

The 2025 quincentenary of the German Peasants’ War offered an apt occasion to advance Werkleitz’s focus on questions of justice in a globalized countryside. This year’s festival comprised interventions in the natural history collections of Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, a film program, and a symposium, and culminated in the exhibition “Planetarische Bauern: Landwirtschaft, Kunst, Revolution” (Planetary Peasants: Agriculture, Art, Revolution). To bolster visibility and secure the project’s footing amid a political turn to the right and cuts to cultural funding, the main exhibition was integrated into Saxony-Anhalt’s multi-venue state exhibition “Gerechtigkeyt 1525” (Justice 1525, using an archaic German spelling) and staged at Kunstmuseum Moritzburg, Halle. Its director, Thomas Bauer‑Friedrich, co-led the artistic direction with Herrmann and, via an open call, recruited Joanna Warsza and Övül Ö. Durmuşoğlu, a curatorial duo experienced in large international exhibitions. Together with the Werkleitz team – Klose, Herrmann, Edit Molnár, and Marcel Schwerin – they formed a two-part curatorial task force that invited 30 artists and collectives.

In 2024, Werkleitz released a podcasts series on the Peasants’ War, and the essay “Planetary Peasants” by Klose, which foregrounded the exploitation of peasant producers under capitalism, was published. [3] Klose called for restoring the agrarian sphere as a primary source of inspiration, energy, and revolutionary dynamics – echoing the 1525 uprising, which Friedrich Engels hailed as the first, albeit failed, revolution. [4] Additionally, since 2022, geographer Jonathan Everts has, in festival lectures and dialogs, advanced “Planetarismus” as a holistic alternative to anthropocentric globalism, embedding human history within Earth history and drawing on Bruno Latour’s and Dipesh Chakrabarty’s accounts of the “planetary turn.” [5] In the 2025 exhibition catalog, Everts defines planetarism as a disposition that accords the planet’s well-being highest ethical authority. [6] Together with Klose’s perspective, it formed a conceptual backdrop for “Planetary Peasants,” recalling the intellectual complexity of the 1525 uprising, which fused radical social critique with Protestant demands, esotericism, and apocalypticism. This concept is articulated indirectly through related articles on “Planetarism” or “Commons” in the bilingual publication, whose 77 entries form a polyphonic glossary. [7]

Olivier Guesselé-Garai and Antje Majewski, “Barric Ode on the Fields (Barrik-Ode auf den Feldern),” 2025

The exhibition itself forgoes chapters and an overarching curatorial text – features one might expect of a biennal‑scale show – in favor of visible scenography and embodied experience. The spatial layout disperses the works across the courtyard and the two floors of the interconnected museum buildings, at times to disorienting effect. Scattered across the courtyard of the ruins of the early Renaissance castle Moritzburg, remodeled into an art museum, a trio of works exemplifies this approach. Daniela Zambrano Almidón and Åsa Sonjasdotter’s The Potato’s Testimonies on the Defense of the Earth (2025) casts the potato as a symbol of both migration and earthly connectedness in a walkable, circular installation displaying different scenes of the vegetable’s cultivation on colorful banners mounted on racks above bags of soil sprouting potatoes. Taking Mother Earth as a common ground, the artists’ self-described ethical-aesthetic practice links central Germany to Huánuco in the central Andes through potato cultivation and its histories. Adjacent to it, Andreas Siekmann reprises his After Dürer installation first shown at steirischer herbst 2019 (Graz), reconstructing the Monument to the Vanquished Peasants from Albrecht Dürer’s 1525 print – an equivocal image of a peasant atop a pyramid of agrarian tools with a blade in his back – encircled by 21st-century signifiers, such as firearms or canned goods bearing portraits of neoliberal economists. [8] This year, Siekmann toppled the column, so the fallen monument coalesces into a barricade or construction site. From there the eye rises to Mikołaj Sobczak’s banner, which subverts the aesthetic of modernist monumental art like Socialist realism and its unitary narratives by collaging discrepant styles and histories: from Frederick the Great inspecting a potato harvest to figures from Soviet-era mosaics by the Ukrainian artist Alla Horska – among them, the Boryviter mosaic of a stylized kestrel, now an emblem of artistic freedom and Ukrainian resistance. [9]

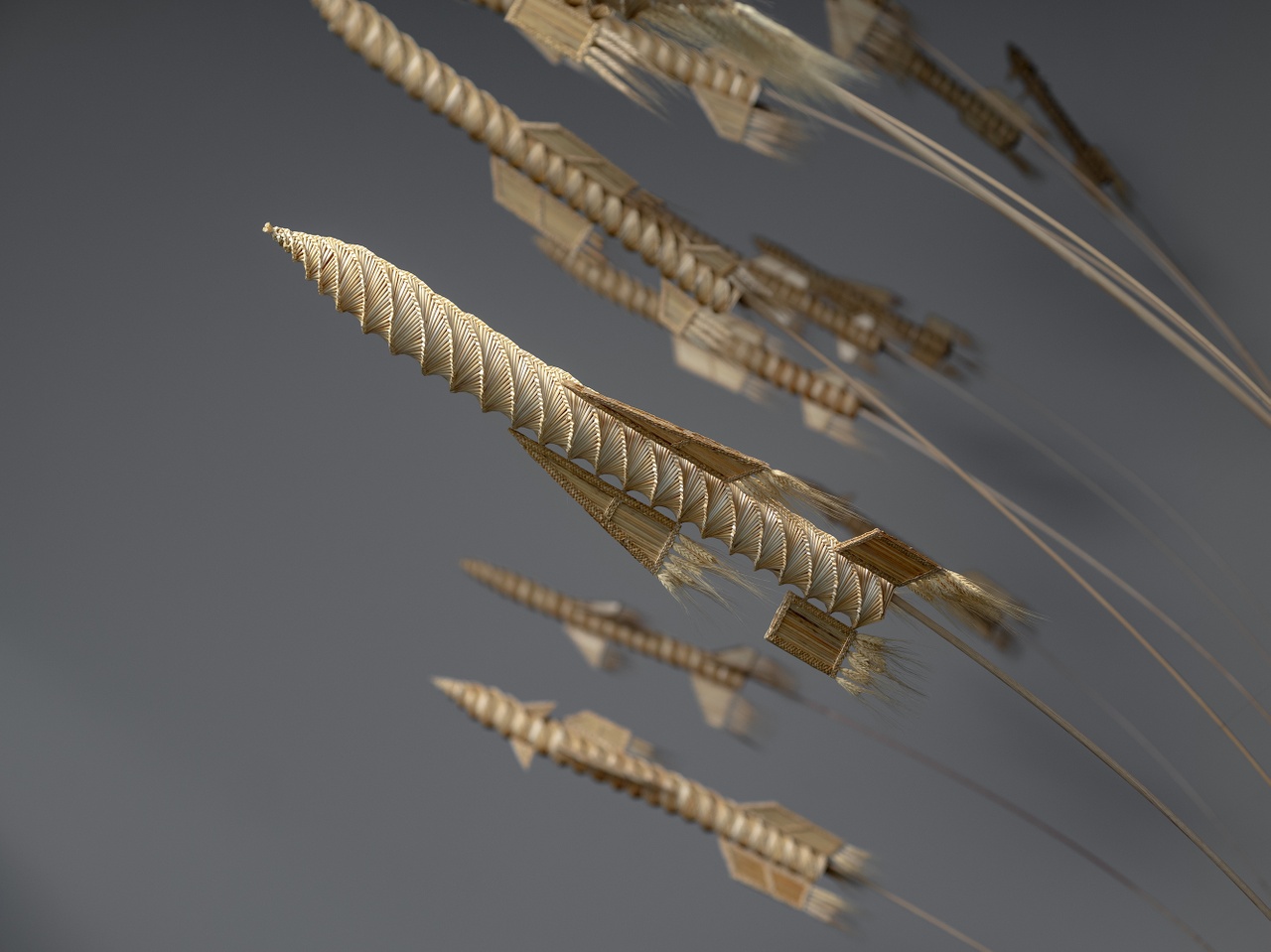

In the large two-story atrium inside, a cluster of installations addresses the contexts of Central Germany and Eastern Europe. Olivier Guesselé-Garai and Antje Majewski’s Barric Ode on the Fields (2025) stages a barricade of rural tools against painted backdrops, like those used in a photo studio, depicting a grid of fields as seen from above – a pattern oscillating between a modernist grid and an aerial photo. Inside the barricade sits a video interview with farmers – perhaps the exhibition’s only direct nod to the recent farmers’ protests in Germany. Above, Anca Benera and Arnold Estefán send straw rockets aloft from a black field, foregrounding the agriculture-weapon nexus. Together these works render the show’s leitmotif – a social uprising that begins on and even in the ground – as a physical vector of ascent from an agrarian barricade.

Chto Delat’s work links local context to the occult – another key thematic axis. In their multimedia installation, the art collective embodies figures from Werner Tübke’s Peasants’ War Panorama in Thuringia, lamenting the vicissitudes of emancipatory struggle and their own exilic trauma, while a capricious wizard toys with everyone’s fate by casting dice. This historical alchemy turns planetary in Viktor Brim’s media installation Saline Operations (2025), where a solar power plant in the Mojave Desert harvests energy from sunlight and stores it in form of a salt repository. In alchemy, salt, gold, and sun signify essence, the desired state of universal perfection.

Edgardo Navarro, “Planetary Mandala, Cycles, Bauernkalender 1-8 (Planetarisches Mandala, Zyklen, Bauernkalender 1-8),” 2025

Some other aisle-protruding “barricades” advance perspectives from the Global South. The NGO Waman Wasi presents communal biodiversity calendars – figurative repositories of ancestral knowledge about human–land relations and cosmic cycles. Supplemented by an image archive and documentary video, these collectively produced colored drawings depict the village cosmos, serving also as guidelines for contemporary communal life. In visual rhyme, Edgardo Navarro’s Planetary Mandala, Cycles, and Bauernkalender 1–8 (2025) blend liberation theology with Indigenous epistemologies in a syncretic neo‑shamanic style. Other works take up decolonial struggles, from Dread Scott’s reenactment of the 1811 German Coast Uprising in Louisiana to Helena Uambembe and Lindokuhle Nkosi’s examination of Protestant missions as a colonial instrument in shaping the South African landscape.

Largely newly commissioned, the works seem to cohere around four axes: agriculture and agroindustry; planetary alchemy; geo-epistemologies; and Indigenous and peasant struggles. They converge on the construct of the planetary peasant that seeks to bridge the divides between agriculture, revolution, and art, yet remains largely speculative. This imaginary subject embodies what might be termed emancipatory planetarism: a holistic perspective linking sociopolitical emancipation to land/Earth/ground.

Planetarism suggests another bridge between the 1525 uprising and contemporary Earth-centered struggles, insofar as they engage esotericism. At the time, as is often the case today, heterodox spiritualities were inseparable from social critique. The movement’s leading agitator, preacher Thomas Müntzer, drew on Meister Eckhart’s notion of the Seelengrund – the “ground of the soul,” the innermost site of divine–human encounter. It articulates a worldview in which the material, spiritual, and social are facets of a single process of perfection achieved by a breakthrough to the “ground.” This breakthrough is re-volutionary – a turning back to immanent essence long repressed: metals mature in the earth toward gold; the human attains divine freedom in the Seelengrund; society advances toward perfection through its ground strata – namely, oppressed groups. Many past and present esoteric currents conceptually inform emancipatory struggles as a break through the “upper” oppressive strata of psyche and society. For example, today, earthbound Indigenous spiritualities of the Global South – such as Mother Earth in Almidón and Sonjasdotter’s work – are often endowed with revolutionary potential to contest the dominance of the Global North.

Anca Benera and Arnold Estefán, “Perpetual Harvest (Immerwährende Ernte),” 2023–ongoing

Recent scholarship on global esotericism enables one to connect its anti-authoritarian and anti-colonial dimensions across geographies. [10] In this register, conservative and reactionary deployments can overlap with emancipatory ones. What if “ground” and its spiritual truth are articulated, for instance, by farmers in central Europe – as in Majewski’s work? Such voices are often stripped of spiritual content and reduced to articulating socio‑political terms. Conversely, esoteric claims from Global South actors – such as Waman Wasi – are frequently granted an automatic emancipatory valence. The result is a blurred sense of the discourse of planetarism in the global art field – of who produces it and how.

This may be the Achilles’ heel of the exhibition and its conceptual proposition, which rests in part on esotericism, yet this reliance is insufficiently reflected and not clearly distinguished from reactionary uses of ground/land/Earth. Consequently, politically ambivalent cases are largely sidestepped or flattened, and planetarism risks co-optation by conservative forces. Holistic thinking is mobilized across the politically diverse field of the global New Age, which can animate insurgencies from emancipatory and libertarian to conservative‑revolutionary. The task, I suggest, is to pursue a more self-aware reappropriation of esotericism in art, anchored in a clear recognition of the inherent ambivalences of concepts such as planetary peasants and planetarism.

“Planetarische Bauern: Landwirtschaft, Kunst, Revolution,” Kunstmuseum Moritzburg, Halle (Saale), May 23 – September 14, 2025.

Nikolay Smirnov is a geographer, curator, and art researcher focusing on geographical imaginations in art, architecture and intellectual history.

Image credits: 1. Photo: Michel Klehm, © Andreas Siekmann; 2. Photo: Michel Klehm, © Olivier Guesselé-Garai & Antje Majewski, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025; 3. Photo: Michel Klehm, © Edgardo Navarro, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025; 4. Photo: Michel Klehm, © Anca Benera & Arnold Estefán

Notes

| [1] | Anne Sailer, “Werkleitz: 30 Jahre Medienkunst in und aus Sachsen-Anhalt,” Mitteldeutsche Rundfunk, September 29, 2023. |

| [2] | The journalist Ulrich Wickert dubbed the fifth Werkleitz Biennale the “documenta des Ostens” on the Tagesthemen newscast of July 31, 2002. In subsequent years the phrase was recycled, but its connotations shifted in tandem with developments in Kassel. By 2025, the comparison had come to signal entanglement in debates over documenta fifteen and its future. See Martin Conrads, “Ausstellung über Bauernkriege in Halle: Der Morgenstern ist nachgebaut,” Die Tageszeitung, May 26, 2025. |

| [3] | Ralf Wendt, “Conversations on Werkleitz Festival 2024 Tank oder Teller [fuel or food],” with guests Friedemann Stengel et al., Werkleitz Audio, 2024; Alexander Klose, “Planetary Peasants,” The Laboratory Planet, no. 6 (May 2024): 2–3. |

| [4] | Frederick Engels, “The Peasant War in Germany,” Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, vol. 10 (International Publishers: 1978), 397–482. |

| [5] | Marold Langer-Philippsen, “02 Jonathan Everts – Planetarismus,” Werkleitz Audio, Podcasts: Umbruch im Film, 2022, ; Jonathan Everts and Daniel Herrmann, “Hunt for the Precious Treasure,” in Mein Schatz, ed. Daniel Hermann et al. (Werkleitz Gesellschaft, 2023), 76. |

| [6] | Jonathan Everts, “What Is Planetarism?,” in Planetarische Bauern: Landwirtschaft, Kunst, Revolution, ed. Christian Philipsen and Kulturstiftung Sachsen-Anhalt (MMKoehn Verlag, 2025). |

| [7] | Christian Philipsen and Kulturstiftung Sachsen-Anhalt, eds., Planetarische Bauern: Landwirtschaft, Kunst, Revolution (MMKoehn Verlag, 2025). |

| [8] | “Andreas Siekmann: After Dürer (2019) Installation,” steirischerherbst’19. |

| [9] | See Liubava Petriv, “Alla Horska’s Iconic Mariupol Mosaic Recreated in Kyiv After Russian Destruction,” UNITED24 Media, June 13, 2025. |

| [10] | See, e.g., Julian Strube, “Towards the Study of Esotericism without the ‘Western’: Esotericism from the Perspective of a Global Religious History,” in New Approaches to the Study of Esotericism, ed. Egil Asprem and Julian Strube (Brill, 2021), 45–66. |