SAY WHAT YOU LIKE Paige K. Bradley on Kaari Upson at Sprüth Magers, New York

“Kaari Upson: Body as Landscape,” Sprüth Magers, New York, 2023, installation view

In an interview published in 2017, Kaari Upson said: “If somebody puts me in front of my drawings, I’d put more text in [them] . [They’re] never finished, but none of my work is ever finished.” [1] Before her untimely death in 2021, Upson established a practice comprehensively in the lineage of other Southern Californian artists such as Jason Rhoades, Mike Kelley, and Raymond Pettibon – particularly the latter’s blaring, drawn signage – with her wildly tense, overwritten drawings of reflective thought, studious citation, and booming declarations cut through with fragments of bodies, though additionally, uniquely, characterized by a feminist approach to dense and accretive cast sculptural installations. The same year Upson graduated from the California Institute of the Arts, I was in extracurricular life drawing classes in preparation to apply to art schools. I enrolled at CalArts in the BFA program the September after she finished her MFA and my life drawing skills as earned became a total surplus until a year later when I used such drawings to get into a different school entirely. I resumed my education by making a proliferation of disfigured drawings and prints that tended to juxtapose image and text – a lot of it.

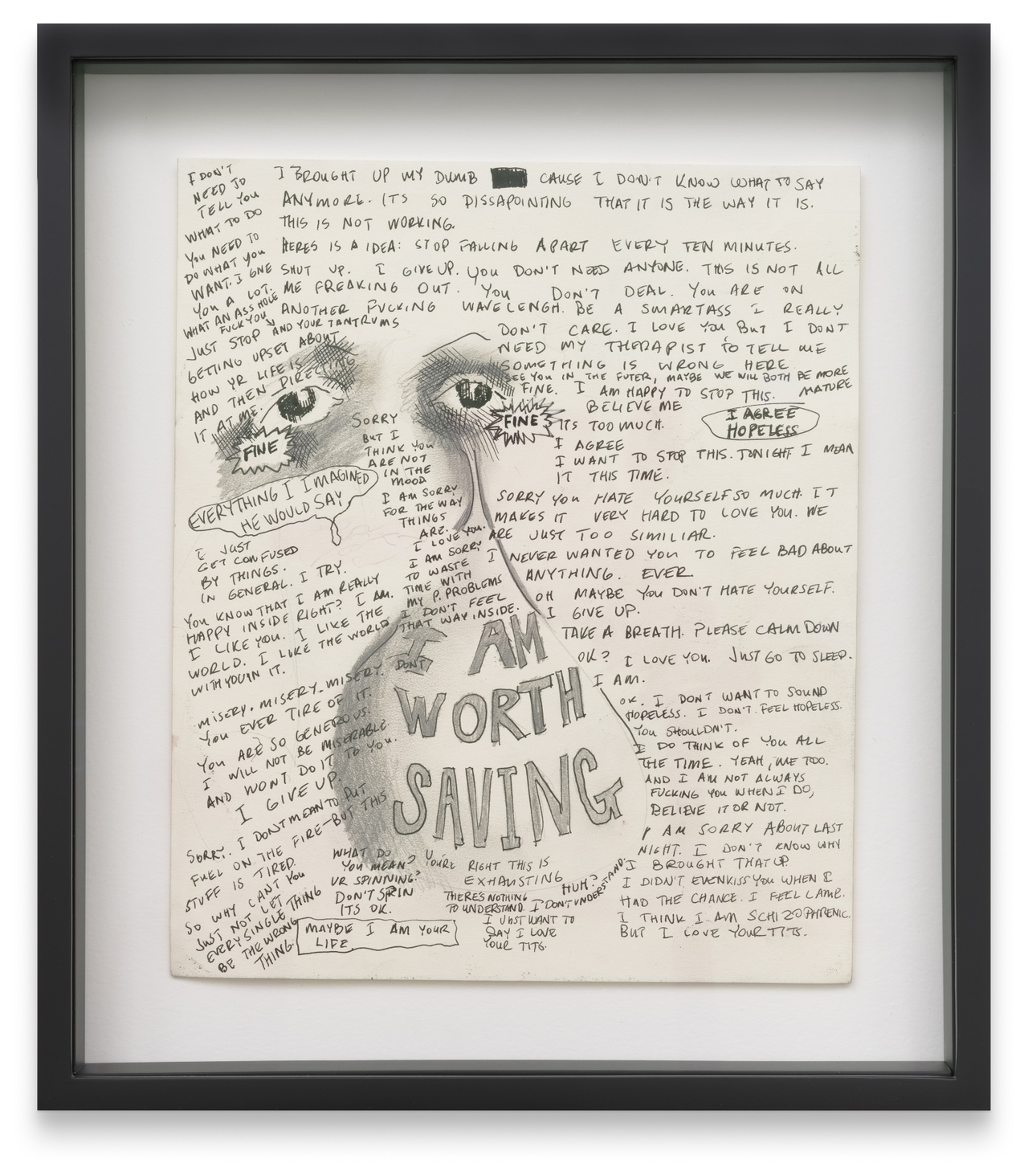

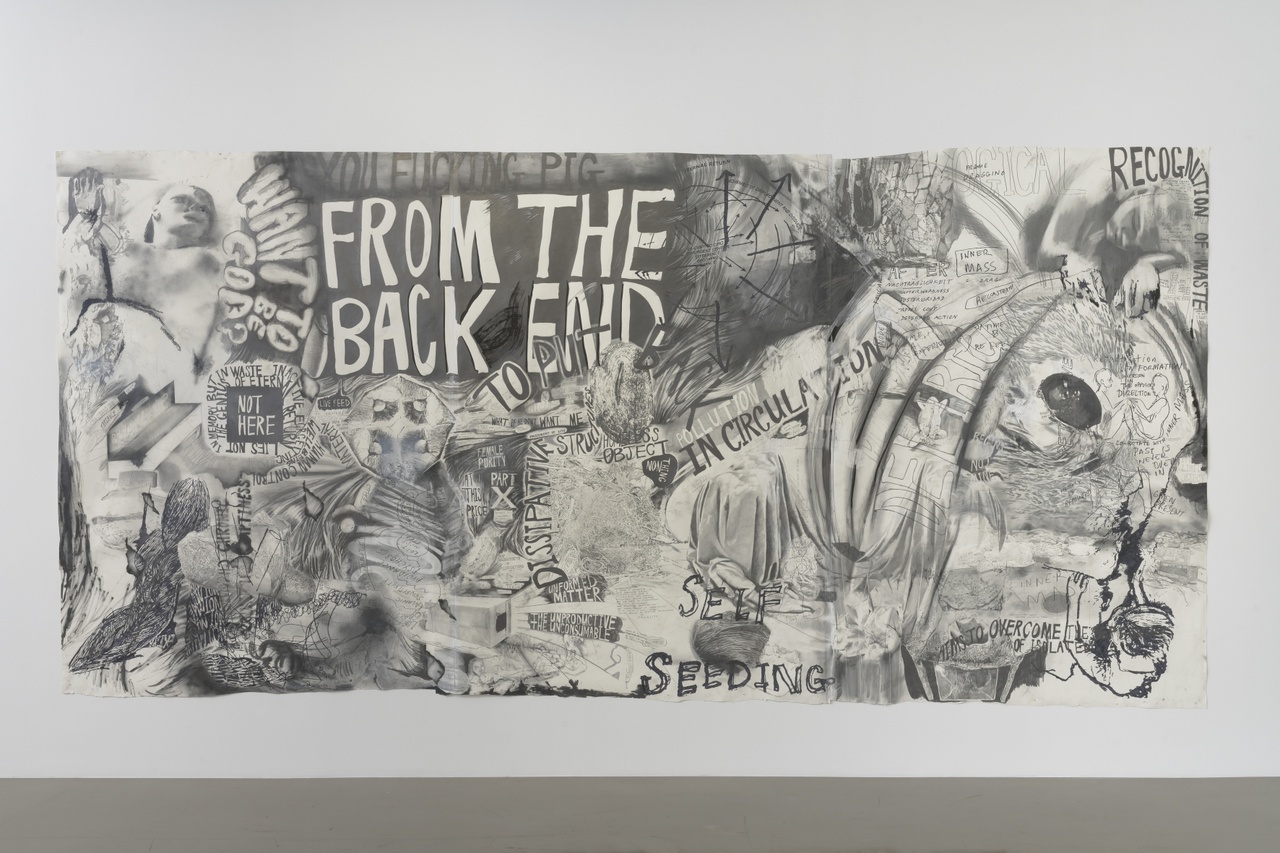

Nobody ever told me about Kaari Upson. Back when I still assumed one of my teachers might do their job and teach me something sometime, they and my ostensible peers could stare at me all they liked, nonplussed, or perhaps exhausted by my seemingly incurable nature or unfortunately nurtured habit of having too much to say and too many sheafs of paper to prove it. I was thinking about Kathy Acker’s unruly juxtapositions of text and pictographic scrawl interspersed across the pages of her 1984 firecracker of a novel Blood and Guts in High School, but no one in my upper year classes then had a clue who she was. Her language demanded too much attention to become legible, ergo she was illegible. Upson, too, made “too-muchness” her calling card. As curator Paulina Pobocha’s obituary for this publication noted, “‘Too much’ never frightened Kaari; she luxuriated in it and made art from it.” [2] Upson drew, and drew and wrote, and wrote and drew across expansive sheets, sometimes working on individual pieces over the course of years. There is cross-talk – her works have competing statements and there is no logical order, so one might say they play with illegibility. The largest of her drawings, Untitled (2015–21), included in the recent, elegantly focused exhibition of the artist’s work at Sprüth Magers New York, measures 530 centimeters across and occupied the greater area of the gallery’s longest continuous wall in the narrow perimeter of a refitted, classic townhouse space. Across from the sprawl of the drawing – which was shown unframed and sports uneven staple marks along its top line, perhaps to allude to Upson’s lack of preciousness in the studio in favor of process – was an assortment of smaller drawings on paper, each bluntly framed in black wood and closely clustered onto the center of a wall. One of these, Untitled (I Am Worth Saving), from 2011, showed the titular parenthetical in all-capital block letters labeled over a cartoonishly oversized tear dangling from one of two shadowed, graphite eyes.

Kaari Upson, “Untitled (I Am Worth Saving),” 2011

The rest of the drawing crams in smaller but still all-caps-lettered statements, which altogether read like a missive that could have been delivered to someone in particular but instead has been put on public display, tuning out any shame associated with private desperation and making it into just another object people can take or leave. At first glance, I hated it. I was repelled, because it looked just like what I used to make when I was prioritizing figuring out the enormity of what I felt instead of identifying a more sophisticated way to communicate it to others, or at least some way that might make them resent me less for saying anything at all. One line of Upson’s text at the bottom of the drawing has a rectangle drawn around it, as if to emphasize her point: “MAYBE I AM YOUR LIFE.” How did she know? It gives me no particular joy to report that now I had to love the work.

The first time I came to see this show, I was mostly ambivalent about the other drawings, too. In the 2007 pencil-on-paper work Untitled (Death Drive), a snaking banner of text alternatively asserts “HELP ME” and “I KNOW WHAT THE FUCK I’M DOING” while underneath it runs the advice: “ACT WITHOUT PERMISSION”. Punk. Rock. On my second visit, I realized something about what I was doing when first faced with Upson’s unabashed complexity, even mess. Or, as she might have called it, “self-created chaos.” [3] My drawings used to inspire a similar averting of eyes, a shuffling of the feet, an occasional cough. At school they were not sure what to do with me, and I likewise perambulated at a distance around Upson’s work in an unconscious echo of my former classmates’ palpable discomfort. An institutional failure can be personal, after all. Going back and repeating the show was like retracing steps – this second time I moved with purpose straight toward her dense worlds of language and explicitly physical gestures as if I were an animal recognizing a creature of its own kind. Safety in numbers.

Kaari Upson, “Untitled,” 2015-21

I had this fizzy notion we had signals to exchange; I opened my mouth; nothing came out; she was not there but her words were, even if they were someone else’s first, and so I read. “Eternal return” was one repeated phrase which leapt out from among the many heavily impressed in graphite or scratched with ink across that enormous, untitled mural of her rich interior life where figurative fragments segued into biomorphic shapes and black holes of hard-rubbed crystalline carbon. Eternal return: it’s frightening – but it’s true. Back in 1998, for a catalogue accompanying the since-deceased artist Ida Applebroog’s survey exhibition in Washington, DC, the writer Dorothy Allison narrated with clarity the stakes of interpreting an artwork: “If we were to reveal what we see in each painting, sculpture, installation or little book, we would run the risk of exposing our secret selves, what we know and what we fear we do not know, and of course incidentally what it is we truly fear. Art … is the projective hologram of our secret lives… . Do you dare say what it is you like?” [4] Like Applebroog’s humbly rendered scenes of barely veiled, quotidian interpersonal violence, Upson’s work also deals in broken stories, [5] with shards flung out in whorls for perfect storms of psychological mirroring. Or, as art historian Lowery Stokes Sims once put it: “artmaking is an extension of social mirroring by the individual through the creation of images.” [6] One might say when looking at her work that “this was Kaari Upson’s world” – are we so sure there aren’t many others who have also dwelled in that society?

Applebroog’s work is associated with a painterly, figurative style, but I’m thinking of how she would arrange her paintings of frequently childlike figures into spatial installations of disjointed narrative, with one notable example being two earlier pieces from her Marginalia series – originally shown at the 1993 Whitney Biennial – which were on view at Hauser & Wirth blocks away from this Upson show. The elder artist’s paintings have uncanny, disquieting, and voyeuristic qualities, and Upson’s drawings are not dissimilar in their rendering of a tumultuous spillage of visual spaces structured by montage. [7] But, just as Carrie Rickey claimed in a 1980 Artforum review of Applebroog’s installation for Printed Matter’s storefront in New York, “[her] windows are really mirrors, reflecting the customs and attitudes of the observer more than revealing anything about the characters depicted.” [8] Upson’s 2017 drawing Untitled (Hysterical Blindness) says, among many other things, “ACT OUT FACTS”. Obviously, there’s a reason I zero in on this phrase at the exclusion of others. It’s like an editorial process; take it at face value. Kaari Upson lifts a curtain on my own intentions, the layering of artifice and performance driven by the hardcore, true, and lived experience. She is relentless. Could that be me? Who is speaking?

“Kaari Upson: Body as Landscape,” Sprüth Magers, New York, 2023, installation view

In between these two walls of drawings was a carefully spaced herd of urethane and pigment limbs collectively titled eleven (2020). Each looked lopped off at the top and bottom like cut logs, and textured bends and folds across their surfaces gave an impression of flesh. Some are more ochre or even rosy, like a healthy person’s, while others looked drained, a wan grey, even a gangrenous blue-green. In a video produced for the 2017 Whitney Biennial wherein Upson talked about a body of work comprising latex casts of abandoned sofas she found around Los Angeles, she described her resulting sculptures as “a form of talking about contamination.” [9] As it turns out, each of these sculptural limbs were cast from both a tree in front of the artist’s childhood home and her knee. Their textural connotations can be intuitively grasped before learning this fact. Looking disjoined, eleven refigures what might constitute a personal image. The artist worked with things we already know and feel – things that uncannily resemble the familiar or what happens in the family, especially when things are all kept within the family. After being pent up, eventually there might be seepage and contamination, even a flood. ACT OUT FACTS.

In life drawing, there’s a particular exercise called the “blind contour.” Students are instructed to focus on the figure or still life set up before them and keep drawing it without glancing at their composition to evaluate their own progress. You are not supposed to look back before the work is all done, or your time is up, whichever comes first. It can be difficult to discern the beginning from the end or where the center of the work lies, but, looking back in a rearview mirror, I can tell that she knew what the fuck she was doing.

“Kaari Upson: Body as Landscape,” Sprüth Magers, New York, September 9–December 21, 2023.

Paige K. Bradley is an artist and writer from Los Angeles living in New York. A former associate editor of Artforum, their criticism has most recently appeared in the New York Review of Books and Topical Cream. Their second book, a long-form art history essay titled Drive It All Over Me, was published by S*I*G Verlag in Berlin and released at Maxwell Graham in New York last October. Their art has most recently been exhibited at Blade Study, Simone Subal Gallery, and Kai Matsumiya in New York and is also included in “CUTE,” a major thematic exhibition running at Somerset House in London through April 2024.

Image credit: © The Art Trust created under Kaari Upson Trust, courtesy of Sprüth Magers, photos Genevieve Hanson

Notes

| [1] | Josh Lucas, “Kaari Upson,” Interview, April 19, 2017. |

| [2] | Paulina Pobocha, “KAARI UPSON (1970–2021),” Texte zur Kunst, no. 124 (December 2021), . |

| [3] | Lucas, “Kaari Upson.” |

| [4] | A larger excerpt of this passage reads: “But what is it we see when we look at a work of art? What is it we fear will be revealed? The artist waits for us to say. ... If we were to reveal what we see in each painting, sculpture, installation or little book, we would run the risk of exposing our secret selves, what we know and what we fear we do not know, and of course incidentally what is is we truly fear. Art is the Rorschach test, the projective hologram of our secret lives. Our emotional and intellectual lives are laid bare … . Do you dare say what it is you like?” Dorothy Allison, “This Is Our World,” in Ida Applebroog: Nothing Personal, Paintings 1987-1997 (Washington, DC: Corcoran Gallery of Art, 1998), 88. |

| [5] | “Ida Applebroog has long dealt in broken stories,” writes David Frankel in an exhibition review. See Frankel’s “Ida Applebroog: Paintings, 1987–1997,” Artforum 36, no. 5 (January 1998). |

| [6] | Lowery Stokes Sims, “The Mirror The Other: The Politics of Esthetics,” Artforum 28, no. 7 (March 1990). |

| [7] | Mira Schor, “Medusa Redux: Ida Applebroog and the Spaces of Post-Modernity,” Artforum 28, no. 7 (March 1990). |

| [8] | Carrie Rickey, “Ida Applebroog,” Artforum 18, no. 7 (March 1980). |

| [9] | “Whitney Biennial 2017: Kaari Upson,” Whitney Museum of American Art, March 16, 2017. |