Rabih Mroué and the Unknown. Pedro de Llano on Rabih Mroué at the Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo, Madrid

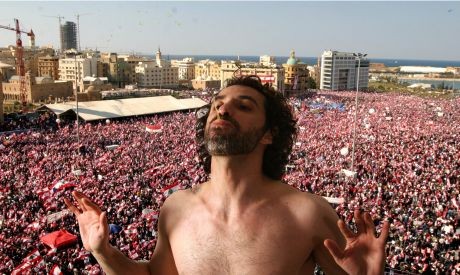

Rabih Mroué, "Selfportrait As a Fountain", 2006/2011

In the mid-1980s, when images of a war-ridden Beirut appeared in the news, it became common, at least in Spain, to describe devastated urban landscapes elsewhere by comparing them to this city. Beirut, known for its beauty and modernity once, had become the picture of apocalypse. Since then, much has changed. Immersed in processes of speculation and gentrification, which coexist with the remains of savage battles, Beirut has recovered its cosmopolitan and bohemian character, to the point of being considered a trendy tourist destination.

The artistic scene is no stranger to this phenomenon: galleries and residencies are mushrooming up, and private collectors plan landmark museums, like David Adjaye´s building for the Aïshti collection. Nevertheless, the region´s chronic instability – first the “Arab Spring”, now the close-by conflict in Syria – renders its consolidation fragile.

Rabih Mroué (1967) knows violent and corrupt Beirut firsthand – riddled with political crimes that carry overtones of noir novels. Educated in theater and performance, Mroué has found an open audience in museums and exhibition spaces for his multimedia creations, which question the status of representation through a constant struggle with the alleged objectivity of the archive. These projects, which he develops often in collaboration with his partner, theater maker Lina Saneh, tend to blur the boundaries of reality and fiction, as well as personal and historical issues. Aesthetically, his work is an heir to Conceptual art, sometimes adopting a dry documentary look which it counter-balances with highly emotional content, while creating ambitious and complex installations in other cases.

“Image(s), mon amour”, the exhibition he conceived with Spanish curator Aurora Fernández Polanco for the Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo in Madrid, revolves around these concenrs, showing a group of works dealing with the conflicts in Beirut and Syria. “I, the undersigned” (2006), is a dramatic opening of the exhibition, a work, presented on a flatscreen, in which Mroué asks for forgiveness for taking part in the Lebanese war: “for its direct and indirect victims”, for his “extremism”. Also for “ignoring the causes of the Civil War”, and considering it “a social classes war”. The framing is simple and straight-forward: just a medium shot with the artist standing in front of the camera. In an uneasy way, it vaguely resembles the images of a terrorist threat, as we have seen them on the news. The spectator remains wondering what is reality and fiction in his discourse. To present this work at the beginning is not an arbitrary decision: it is specially meaningful in a country like Spain, which also suffered a Civil War, and where very few have accepted their responsibilities, and no one has begged pardon publicly for the damages caused.

Other works that come to attention within this first group, dedicated to the war in Lebanon, are “Old House”, (2006), a looped video of the demolition of a building in Beirut, accompanied by a text, in which Mroué highlights the need of telling the stories of the war, again and again, “not in order to remember, but to be sure of forgetting them”; or “Vienna” (2006/10), a visual comparison between the architecture of Vienna and the ruins of Beirut, projected on a postcard fixed to a wall, at low height, near the floor, with alternating images of both cities. It finishes with a statement of hopelessness, written on the postcard: “All will be in ruins since the beginning, and not even an angel sent by God can do anything about it”.

Rabih Mroué, "Old House", 2006, film still

More recent pieces, such as “Swear with Fire and Iron” (2013), show with intensity the autobiographical content of his project. Two sound recordings replay the artist’s brother singing a popular song about resistance to war; first when he was a child, and secondly after being injured in a shooting, years later, already as an adult. Emotive and blunt, Mroué’s investigates his family ties, his past and present.

Against the autobiographical content of the first part, the second block of pieces contrasts with its disturbing anonymity. Here, the works deal, in different ways, with videos filmed by Syrian citizens on their cell phones, accidentally recording their own unexpected death, and later uploaded to the internet. These images – quite similar to each other; often brief in duration and with the same mix of nervousness, excitement, and furtiveness - are processed by Mroué through a fictional version of one of these scenes, in a 16 mm film, performed by two actors; a set of editions of the real videos in the format of flipbooks, titled “Thicker than Water” (2012), accompanied by a soundtrack that the visitor can optionally play (pushing a button next to each flipbook, that triggers the noise of a shot); and a video-conference, “Pixelated Revolution” (2013), in which the artist reflects about the nature of these documents, its authenticity, and the possible meanings of the involuntary act of filming the instant which marks the passing from life to death, usually signaled by a shaken view of the sky, or a sudden fade to black.

These images lay out ethical issues. In fact, other artists have worked with similar materials, in different contexts, resonating with Mroué’s pieces on Syria. For her series “Death” (2011/12), Palestinian artist Ahlam Shibli photographed portraits which, as sorts of domestic altars, commemorate the many martyrs of the Second Intifada (2000-2005) in Nablus. Each of these images is addressed by a wall-label where the viewer finds details about the individuals represented, out of the field work and research made by Shibli herself. Patricio Guzmán, as a second reference, is the author of a work conceptually closer to Mroué: “La batalla de Chile” (1972/79), a documentary dedicated to Leonardo Henrichsen, the cameraman who filmed the “tanquetazo” – a coup d´état attempt, previous to the decisive one of September 11th, 1973 –, and was shot to death by a soldier during this riot. These examples state the need to remember the names of those who succumb to war, as well as the efforts for justice which means denouncing the murderers.

Rabih Mroué, "Image(s), mon amour", Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo, Madrid, installation view

Mroué’s pieces, however, do not offer any information about the assumed victims that appear on the appropriated images from the internet. The artist did try to identify the attackers, by freezing and blowing up the images from the internet videos, zooming in on their faces. The result is a series of “portraits” that were part of his work for dOCUMENTA (13). The lacking resolution of these images, which get pixelated when one tries to look for details, keep the identity of the murderers in a degree of irreality or abstraction. This failure of technology emphasizes the fear, dehumanization, and injustice that characterizes anonymity in war situations. A feeling that grows since we are left without – almost - any information, except the internet images themselves - about the victims: when were they killed? Who were they? Why were they there? Representation is addressed not as an answer to the basic journalistic questions, nor as a homage or tribute to the victims of war. In these works, representation is merely an uneasy enigma.

Rabih Mroué, “Image(s), mon amour”, Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo, Madrid, September 27, 2013 –February 2, 2014.