NIGHTJAR INCANTATION Sam Finkelstein on Justine Kablack at BUOY, Kittery, Maine

“Justine Kablack: whip-poor-will,” BUOY, Kittery, Maine, 2021, installation view.

Located in Kittery, Maine, the southernmost town in the northernmost state on the US Eastern Seaboard, BUOY is a particularly suitable site for a constellation of 25 drawings and sculptures that read as visual records of supernatural encounters. The gallery’s peripheral location provides an analogue to the subject matter presented – composed primarily in graphite on paper – that evokes the type of experience most readily available at the threshold between here and beyond. In the case of “whip-poor-will,” Justine Kablack’s first solo exhibition with BUOY, I found it helpful to consider the colloquial adverbial usage of “super,” meaning “especially” or “particularly,” over that of its prefix form, as Kablack’s works, almost all of them created since April 2020, very quickly cast a spell on my ability to discern “artifice” from “real,” and the “natural” from the “otherworldly.”

Kablack infuses the mystical into the realm of plausibility through delicately rendered images that read as if they were drawn en plein air at the moment of encounter. The content of the imagery feels so familiar – dark nights illuminated only by inexplicable flickers, an illegible reflective street sign, the glint of a flower’s petal, car lights shining on a wedge of pavement – and is so deeply rooted in the rural collective unconscious that the artist’s depicted narrative could be confused for one’s own.

The drawings in the show fluctuate between soft, atmospheric gradations of value in works like Phenomena 1 (2020), which leaves a blank swath of paper to articulate a comet-like form flying over a quiet mountain range, and A Message (2020), in which dense blocks of black evoke both the vastness and sheer flatness that the night brings. With prolonged observation, these voids slowly reveal nuanced forms, a process akin to the way an environment takes shape as one’s eyes adjust to a dark space before finding the light switch. The content remains slightly obscured, some of it still hidden in darkness, leaving a sense that the drawings withhold an enigmatic higher truth. Tempering my impulse to decipher felt like part of an intended discovery process.

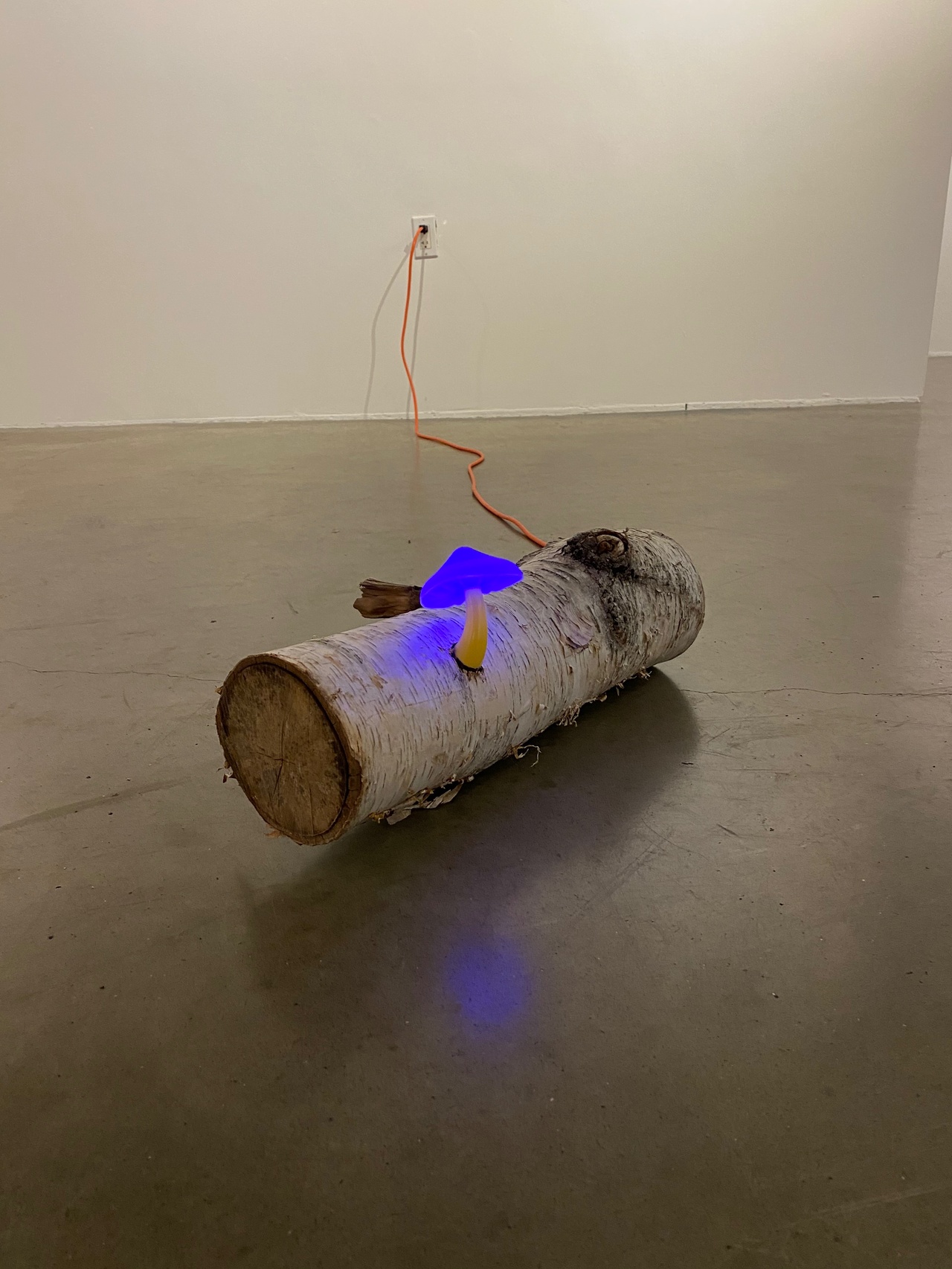

Justine Kablack, “Log Magic,” 2020.

In Maggie Nelson’s prose poem Bluets, she points to the possibility of a higher truth in darkness, through the first known incantation of “Divine Darkness.” She recalls the writings of the mystical theologian Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, a late 5th-century Syrian monk who prayed “that we may come unto this Darkness which is beyond light, and, without seeing and without knowing, to see and to know that which is above vision and knowledge through the realization that by not-seeing and unknowing we attain to true vision and knowledge.” [1] Nelson responds that “the Divine Darkness appears dark only because it is so dazzlingly bright – a paradox I have attempted to understand by looking directly at the sun and noticing the dark spot that flowers at its center.” [2] The oscillation between total presence and total absence of light is evident in Kablack’s surfaces: so richly built up that the graphite makes paper darker and darker until it becomes lustrous.

Portal 3 (2020), a drawing propped up to eye-level by a skinny tree branch, depicts chain-link fencing with a gaping hole in the middle. The links appear to be illuminated by a flashlight, but where one would typically see an abyss, we are instead presented with a shining blotch of darkness. This alluring, shimmering sheet, with stick support, taking on the form of a woodland looking glass, induces a psychic state that reflects and whispers what is essential to pure existence.

While not technically a metal, graphite is the only nonmetal capable of conducting electricity. This elemental loophole confirmed my intuition that the works before me are conduits for energetic exchange. Reinforcing this assertion, Kablack makes no effort to hide the orange cords that power two floor sculptures: Log Magic (2020), a length of birch trunk illuminated by a color-changing mushroom-shaped LED light, and Leaf Magic (2020), a pile of maple leaves with a small screen nested in its center that displays footage of a slug moving sluggishly on forest ground. These two mimicries of the natural, along with the plastic slug resting on a wooden artist’s frame that hangs a few feet from its virtual doppelgänger, initially draw attention to themselves as obvious imitations of the “real” objects they signify. Kablack, accepting the futility of attempts to distinguish between “reality” and “simulation,” shrugs indifference at the way constructions are often interpreted as truth, and vice versa.

“Justine Kablack: whip-poor-will,” BUOY, Kittery, Maine, 2021, installation view.

Although sculpture generally meets the precondition for objecthood, drawings have historically played the subservient role of preparatory elements for grander works. Despite this, Kablack endows her drawings with autonomy through various framing techniques, including suspension in framed glass; mounting onto stretched-hide-like constructions; and self-contained, hand-illustrated borders of faux wood grain or ornamental flora and fauna. In the spirit of the Pattern and Decoration movement, Kablack subverts the default historical location of frame-as-supplement by establishing a more honest interdependent support system between the interiority of the image and what separates it from the rest of the exterior world. Craft theorist Glenn Adamson muses on the expansive zone the supplement typically inhabits:

For if the frame is supplemental, then surely the rest of the picture gallery is as well – we require the full apparatus of the space to understand the work as having a certain prominence and value. And what about the parts of the gallery – the carpet, the lights playing on the painting’s surface — or the building that houses the gallery, the streets and parking meters outside? [3]

This theoretical exercise, inspired by themes in Jacques Derrida’s The Truth in Painting, seems like an inexhaustible source of incorporating additional signifiers until one has run through all possible iterations of cause and effect across the infinite expanse of time and space.

The osmosis that takes place between “whip-poor-will” and BUOY, between the artworks and the gallery’s space, intimately integrates the two through their porous, receptive natures. Deep Hollow (2020), a water-filled, black five-gallon bucket at the entrance of the space, looks as if it could have been placed there to catch a ceiling leak. Upon closer inspection, the work declares itself a sculpture, Kablack going so far as to scratch the title in a layer of built-up graphite in the depths of the container. Shadeless windows allow observation of the show from the outdoors, which disrupts one’s spatial orientation upon returning inside. The sequencing of illustrated windows and real windows, and the way both radiate light or darkness depending on the vantage point and time of day generates an overwhelming sense of simultaneity. Maine winters are notorious for their limited daylight hours, which makes it entirely possible for one to experience this spatiotemporal confusion during a mid-afternoon gallery visit.

It feels entirely appropriate that the show’s namesake never manifests in visual form. Whip-poor-wills are well-camouflaged, seldom-seen birds of the night that tease and seduce with trance-like chanting from the safety of leaf litter and tree bark. Leaving the gallery having consumed the tromp l’oeil moths and flies rendered with such sensitivity that they just barely evade the illusion of flying off the page, I began to feel the way the nightjar must feel after foraging for its newborns on a full moon: perched just off the ground, sated, and entirely at ease in silence. My gaze met two glowing orbs that may belong to some nocturnal beast or, just as readily, to the luminescent celestial bodies of Jupiter and Saturn in conjunct.

“Justine Kablack: whip-poor-will,” BUOY, Kittery, Maine, December 18, 2020–February 12, 2021.

Sam Finkelstein is a sculptor currently based in Rockland, Maine.

Image credit: courtesy of BUOY and Jenny Calivas.