CALL AND RESPONSE Cecilia Bien on Christine Sun Kim at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

“Christine Sun Kim: All Day All Night,” Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 2025

Between 2007 and 2014, Christine Sun Kim advocated for the disabled community she self-identifies with by way of “Whitney Signs,” a program developed at the museum to offer tours in American Sign Language (ASL), both live and in vlogs, for assisting visitors with their experience of the artworks. [1] Subsequent display of her own work in 2018 and an invitation to the 2019 Whitney Biennial recoded Kim’s position in relation to the institution from educator to artist. Now, Kim has returned to the Whitney once more with a survey of over 90 works made since 2011. “All Day All Night” begins on the museum’s eighth floor with mostly drawings in charcoal or pastel – in addition to a few ceramic sculptures, video works, and documentation of performances – against the backdrop of a mural featuring a wavy musical staff. On the immediate wall opposite the exhibition’s entrance and throughout the subsequent rooms, uniform notations along with the staff are hand-painted in acrylic, imperfect to remind us of their human quality, demonstrating what momentum looks and feels like when it has the opportunity to go large-scale. The mural is titled Ghost(ed) Notes (2024/25), partially in reference to the experience of being ghosted. These kinds of contemporary colloquialisms are invoked throughout the exhibition in works with titles such as Sorry Not Sorry, Sorry Zero (2018), ostensibly to transcend their relevance beyond the Deaf experience that the exhibition otherwise centers on.

Visitors using the stairwell to descend encounter A String of Echo Traps (2022), three animated light boxes hanging from cables. Playing with the ASL sign for “echo,” their LED animations feature arching black forms in motion, resembling both a repeating sound wave and the hand movement used when signing the word “echo.” The black arches expand and then contract, bouncing off each other before giving way to the white negative space, while a soundtrack by Matt Karmil synchronously plays white noise. Following the light boxes down to the third floor, visitors find the mural Prolonged Echo (2023/25), which features the same shapes but at the scale of the museum walls. The reference is repeated in smaller drawings of the curves, titled Small Echo (2022) and Long Echo (2022), as well as in two larger drawings of thickly layered charcoal closing in on their white ground, each titled Pointing (2022), all placed on top of the mural as if to highlight the redundancy of the echo. On the ground floor in the lobby area, more drawings and a kinetic sculpture continue to point to the physicality of language.

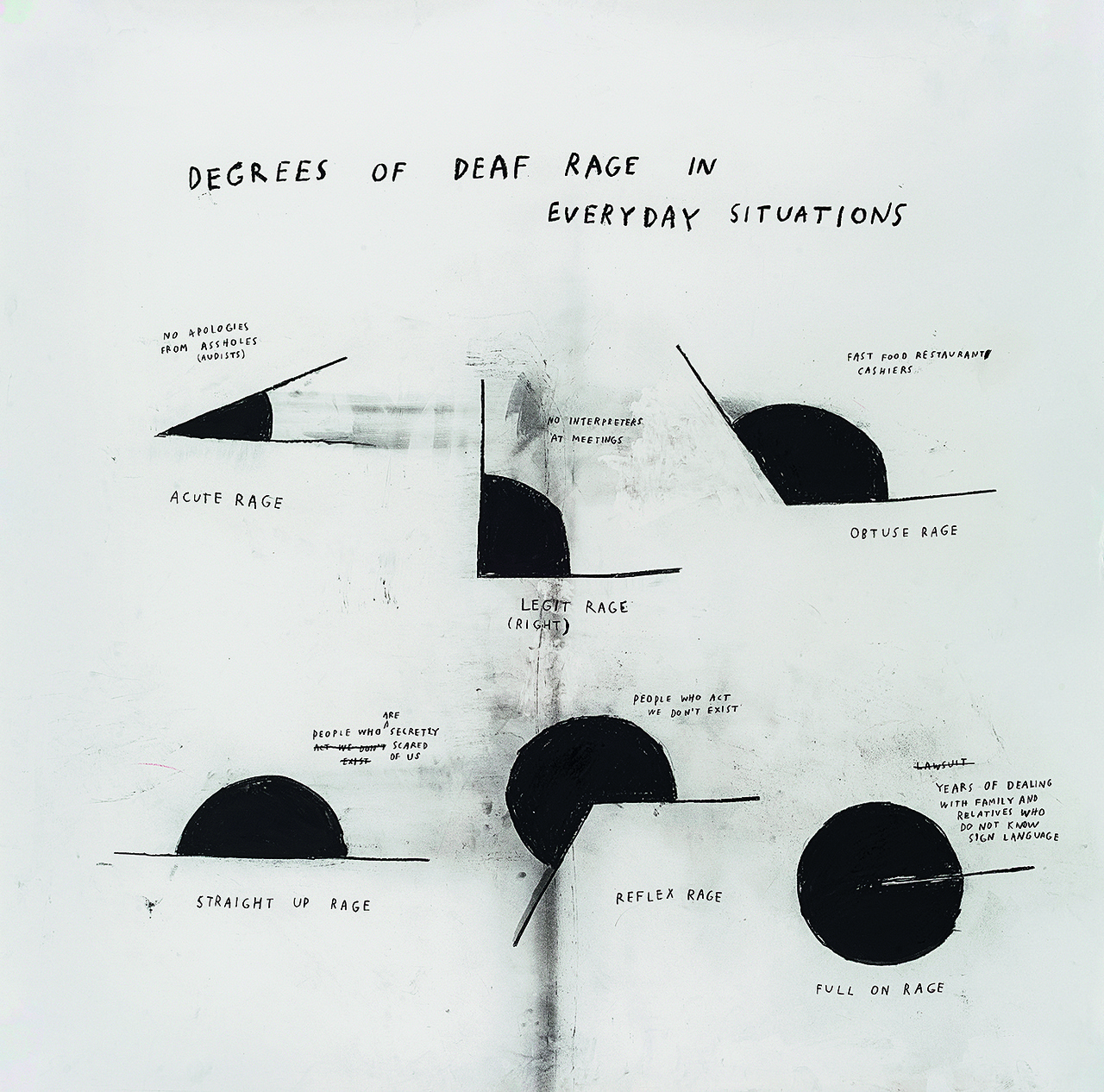

Christine Sun Kim, “Degrees of Deaf Rage in Everyday Situations,” 2018

Kim’s access rider, a Google document – that by implication is subject to change – written in collaboration with her Los Angeles gallery, François Ghebaly, is distributed to the press as a guide to avoid words that would make describing the artist, and the group she identifies with, feel misunderstood. [2] The decision to oversee how Deaf and disabled artists are described is understandable, considering the broader historical context of discrimination and reductionism in art history and culture. The necessity of the document is attributed to Kim’s reliance on interpreters (distinct from translators; see the access rider) who orally convey her signing, an act that carries the implicit risk of miscommunication. Kim has disclosed in an interview the intricacies of working with interpreters: “Some are power hungry, some aren’t suited for my personality, some I’m too close to. And so it’s about how I have to work within the interpreter’s personality. If somebody is soft-spoken and that’s how they always talk, well then I’m going to sound soft-spoken.” [3] The power dynamics that emerge when a third party is depended on for non-written communication exemplify the complex relations inherent in language. The process of interpretation may thus essentialize the wide gap between how meaning is conveyed and how it is received. Yet prescribing or negating word choices used for press coverage, per the access rider, as a solution for eluding potential misinterpretations likewise produces essentializations within the range of meaning between the writer’s intentions and the reader’s own sensibilities.

In the current version of the access rider, Kim writes, “[…] centering my deafness […] can be reductive and othering.” [4] While a practical warning, it is also one to reckon with, since the exhibited works center on the artist’s condition as if it is intrinsic to her practice – or rather, career. Throughout the exhibition, to “deafsplain” – the artist uses this term in Future Attempts to Deafsplain (2016) – is portrayed via playful, albeit too often facetious, strategies that are particularly pronounced in diagrammatic drawings. The data for the sketched infographics, as they’re referred to by Kim, is not derived from census-gathering but rather the artist’s own experiences of doubling down on rage, featuring literal titles such as Degrees of Deaf Rage in Everyday Situations (2018). [5] There are a total of six charcoal drawings in this series, which cover different scenarios where rage may be extracted, such as being in the art world, in educational settings, and traveling, drawn as geometric angles so we know when the artist is at her most outraged (close to 360 degrees) and when the rage is considered cute (acute angle; wordplay noted). Punny semiotics are tinted with indignation in Future Base (2016), a series of twenty drawings, neatly mounted for the exhibition in four rows of five, which play on the motions of the hand when signing the ASL word “future.” The movements, Kim shows us, look like the double arches of the McDonald’s logo (hence one drawing titled McFuture), or could be mistaken for a stitched design on the back of a jeans pocket (as in Future Denim), or follow the trajectory of a hole-in-one golf ball (as in Future with White Privileges).

Kim’s drawings may want to exude irony and sass, but the veritable flippancy dilutes their agency. Rather, the artist’s strength and innovation shine without the snark in collaborations during the period in which she also worked as an art educator. Performances such as Courtier as Courier (2013) and Face Opera II (2013), both shown as video documentation for the exhibition, signal the risk and humor that lingers in an in-between space where slippery points of contact may be lost in interpretation. Courtier as Courier draws on The Book of the Courtier (1528), a tale of merchants and buyers who speak different languages and fail to communicate across a frozen river via interpreters. Kim reimagines the story by programming a scrolling narrative text onto iPads, which she places around an exhibition space. Throughout the performance, Kim moves about the space, controlling the pace of the passing words to question the immediacy of the transmission of meaning when a word is heard versus read. Face Opera II likewise incorporates texts prompted on an iPad. Performers attempt to convey the words’ meanings and emotional attributes using facial expressions, which provide the grammatical structure for signing, to another group of performers who attempt to understand them. The two groups mirror each other’s facial movements and expressions, making visible the risk of misinterpretation while also hoping to arrive at a shared understanding. In Face Opera II, provocation of the articulating face is emphasized in lieu of the spoken word while both the signers and the group trying to understand them rely on intuitive faculties to be able to understand each other without reducing or conflating the other with the self. Negotiation is thus not only between the self and other, but also between the othering of self and self-ing of the other.

Christine Sun Kim, “-Courtier as Courier,” 2013

“All Day All Night” is not chronologically organized, yet in between Kim’s earlier and later works, a chasm is apparent where the artist’s self-identification becomes a self-othering used to frame her practice. However, as with most art in which the artist’s otherness is centered, it becomes difficult to separate the work from its projected alterity. In 1993, then Whitney director David Ross defined a new American art on the Charlie Rose show by describing intentions for the upcoming biennial, in addition to the future of the museum. Ross argued against art’s autonomy and for its role as an agent of social change by showing artists who would engage with issues reflecting their communities. Ross’s definition of community aimed to address different ethnic and racial groups that could encompass American art outside of the Eurocentric tradition, which would also fulfill the ideologies of multicultural pluralism. [6] Yet with postcolonial politics already in the process of being absorbed by multinational capitalism, center and periphery took on a new relationship where the position of the marginalized could no longer be projected onto the subaltern artist from the Global South or, more generally, the person of color. As a result, new checkboxes for who could reflect – or rather represent – the socially oppressed, and therefore politically transformative, emerged. Now, as identity politics deployed since the mid-1990s by institutions as social outreach and tacit public relations are subject to elimination if conservative policies take hold, one has to ask what the consequences will be for art that relies on a narrative of otherness. The exhibition’s default of emphasizing Kim’s condition is perhaps more a symptom of the recent – yet soon to be former – state of cultural politics rather than a reflection on the limits of the artist’s range. Here, the artist has chosen to lean into the institution’s projection of otherness by way of garnering the necessary recognition, resources, and platform, until self-making becomes an artist’s self-branding that, instead of critiquing the institution, seems to ask: Why not appropriate its means to an end?

A problem with institutional deference to the perceived other as having automatic access to political and therefore artistic transformation is that we as an audience become complicit in maintaining the end goals of othering if we consume it according to the institution’s narrative, projecting responsibility onto the artist whose subjective experience stands in as expertise for social change. [7] On the other hand, with recent DEI funding cuts in the United States removing access to interpreters and threatening organizations for disabled communities that are supported by federal grants, using the art institution’s turn to identity politics may also be a means of rechanneling access to funding. [8] At this point, the question is for Kim – and how much she believes in her work beyond the conjured outrage and the call-and-response of arts’ politics. To follow her intention to reclaim sound and use her work to, for example, show what notations and scores can do visually beyond decor may require removing the self from the projection of alterity. Down the street, at the same time as the opening of “All Day All Night,” the Drawing Center showed John Zorn’s compositions, which he calls “music without sound”: chance operations using complex, illustrated scores as their only language. Julius Eastman, shown simultaneously at 52 Walker, eschewed traditional use of notation to encourage improvisation based on feeling, using the score to its very ends in places where it was not accepted. These are both dudes working under different circumstances, and this writer does not intend to compare or ask for Christine Sun Kim to live their legacy. It is rather a challenge and belief in the potential for Kim to show her range beyond referencing her condition sleight-of-hand or in-your-face.

“Christine Sun Kim: All Day All Night,” Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, February 8–July 6, 2025.

Cecilia Bien is a writer based in Vienna and New York.

Courtesy Whitney Museum, photo Ron Amstutz

Notes

| [1] | See “Christine Sun Kim, All Day All Night,” access rider, Google document, accessed March 15, 2025. |

| [2] | Christine Sun Kim, “How I Became an Artist: Christine Sun Kim,” conversation with Emily McDermott, interpreted by Su Kyong Isakson, Art Basel, May 26, 2022, accessed April 4, 2025. |

| [3] | Christine Sun Kim, “Christine Sun Kim Writes in All Caps,” interview by E. Alex Jung, SSENSE, February 7, 2025. |

| [4] | “Christine Sun Kim, All Day All Night,” access rider. |

| [5] | Tom Finkelpearl, Jennie Goldstein, and Pavel S. Pyś, eds., Christine Sun Kim: All Day All Night (Walker Art Center, 2024), 21. |

| [6] | David Ross, interview by Charlie Rose, The Charlie Rose Show, March 5, 1993. |

| [7] | Hal Foster, “The Artist as Ethnographer,” in The Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century (MIT Press, 1996), 171–204. |

| [8] | Major support for “All Day, All Night” has been provided by grants from private non-profit foundations: the Ford Foundation, Teigler Foundation, the Terra Foundation for American Art, and the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. |