Hiding in Plain Sight Rachal Bradley on Merlin Carpenter at Simon Lee, London

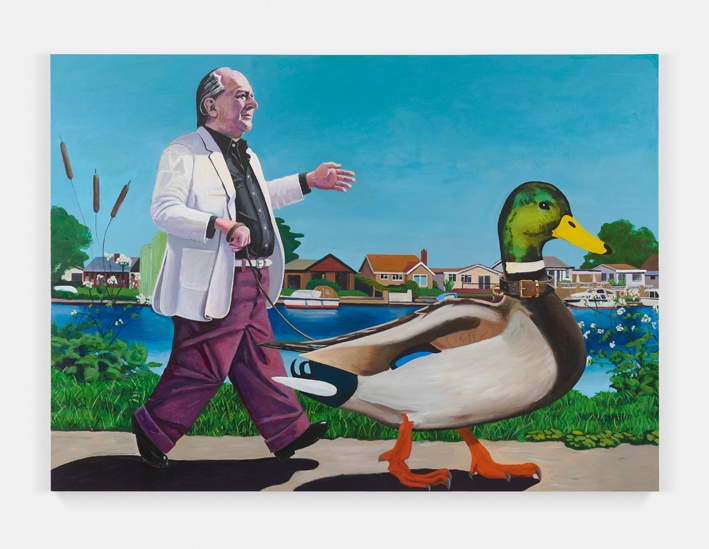

Merlin Carpenter, „J.G. Ballard, Drives an Allard, Goes For a Walk With His Pet Mallard“, 2019.

I recently visited a friend; perusing his bookshelves, I noticed several old-looking volumes next to the Houellebecq and Don DeLillo. The cover of one of these books fell open to reveal a handwritten dedication, signed off by Martin Heidegger. Turns out my friend’s grandfather was Heidegger’s pen pal.

In Merlin Carpenter’s painting This Is What Happens When You Collaborate with Nazis: Professor Martin Heidegger Trying to Escape by Bike from the Approaching US Army, Spring 1945 (2019), Martin Heidegger again stares toward me. His portly, cartoonish body looms large in the central foreground of the big (240 x 190 cm) painting. He is wearing traditional German (specifically, Swabian) attire with clumpy, simply rendered brogues and hiking socks. He is gripping a shiny red bicycle, caught in the act of flight from complicity. The figure more resembles a vintage children’s story character than a significant figure from 20th-century continental philosophy.

The painting’s extensive title apes a condescending tone, refusing to mollify the relationship between Heidegger and National Socialism. Yes, he was a radical and seminal philosopher, but – here’s the catch – he was also a Nazi. Not a sympathizer who was kind of into it for a bit early on, but a full-on believer, holding the position of Rector at the University of Freiburg with the support and collaboration of the regime, a position he used to proffer damaging information on other colleagues to the authorities. Carpenter’s use of Heidegger’s image/object position in history and culture poses a significant question: Do figures of ambivalence make for good images? Carpenter moves the hermeneutic loop of painting out from the interpretive realm to the constructivist and critical, thereby addressing some nuts-and-bolts questions about value in image-making. This is effective because he is a good painter of bad painting. The use of an ambivalent subject within this good/bad painting binary creates a further ambivalence in the medium of painting, one that doubles back into an analysis of the value criteria involved within representation but also is crucial in the exercise of a reflexivity on the status of criticality itself, steering the paintings to the cliff edge of criticism and spectacle.

When addressing mythical ambivalence and its commensurate ricochet into image-making, there is a necessity for attending to the medium of paint. This is an oft-overlooked aspect whereby the image/object is permitted to dominate the enquiry, resulting in only the reproduction of the image/object’s dysfunctionality within the very delicate space of critique of the operation. The painting’s potential to operate as mirror perpetuates outward into image/painting/object, doubling down on the dysfunctional rather than holding open a slithering gap for reflecting on its operation. But what happens when the subject is pure image? In Art Prep: Draw Cara Delevingne and Kate Moss and Art Prep: Draw Kate Moss and Cara Delevingne (both 2019), the two British fashion models are depicted in a familiar paparazzi-style image, eyes cast downward away from the camera/gaze of the viewer. Moss is rendered alongside her younger protégée in wonky yet controlled layers of straw yellow and heated pink nudes. Their faces are at the point of shift between painted mark and plane, subtly disturbing their famous million-pound symmetry. It is as if their bodies (where value is shored up) are one stroke away from slipping off of the surface. As with the works’ titles, each painting is read literally from left to right: firstly Cara to Kate, with the figures then mirrored in the second painting, Kate to Cara. Carpenter has both laid out the instruction for production and faithfully followed its execution in order to then in turn instruct us, the viewers, on how to read the final outcome. In this sense, the gesture is both totalitarian and yet provisional (art prep for what?), mimicking the moralistic imperative of the Heidegger painting. In this wobble, Carpenter presents the very edge of the dilemma of how we decide whether something eschews moral value, and whether this is separate from or constitutive of artistic merit.

Merlin Carpenter, „Art Prep: Draw Kate Moss and Cara Delevingne“, 2019.

Considering these works, I am reminded of Richard Hamilton’s Swingeing London 67 (f) (1968–69), a work of painting and screen printing based on a paparazzi photograph of Mick Jagger and the art dealer Robert Fraser, showing each in handcuffs as they are transported to a court appearance on drugs charges. Hamilton utilized the social moral outrage behind this image to reflect on the value status of the image, and on the insatiability and morbidity of the public fascination with celebrity. Carpenter’s twinned paintings reflect the complete absorption of this operation into the image economy. Paparazzi photos garner significant payouts, and celebrities now intentionally stage these shots in order to boost their visual value, which they consolidate into hard cash in the form of endorsements. It is now completely understood that visibility is profitability.

The press release claims the earnest adolescent figuration on display here is “hyperrealistic […] push[ing] the boundaries of painting into the discourse of ‘readymade.’” But what the author of the press release has missed is that, in the context of a Mayfair blue-chip gallery, paintings are “readymades,” and that this is suggested more in Carpenter’s beautiful stretchers, the infrastructure of the operation, than in the style of rendering. In this respect, Carpenter is several steps ahead of the gallery in his assumption that readymades are themselves hyperrealistic. Where the status value of the painting as hyperrealistic object meets another paradox of operation through the ambivalent cultural figure, the simulacrum-like ricochet is profound. Not everyone is an icon/image/object in the same realm – the cult writer J.G. Ballard features in another painting walking a mallard duck on a leash for example. The hall of mirrors smashes around as you bounce between Heidegger, Cara, Kate, Ballard and the mallard. The resulting shrapnel refracts out the cryptic details in each painting: the volcano behind Heidegger, the mallard’s blank eye [1] , Kate’s blobby leopard-print scarf. These paintings have an accumulative energy they gain with a furrowed brow. I for one am glad Carpenter hasn’t opted for hyperrealism, as this approach places more emphasis on the painting as readymade. By accessing the earnestness of a student of art, Carpenter gets much closer to the readymade-ness of the painting/image/object, a play on what a painting should be, as based on received value systems: realistic, symbolic, big, colorful, background, foreground. There’s a slippage between this imperative and the paintings‘ deft execution that relieves the works from an overly ironic or cynical treatment. The internal references (the visual and cognitive backdrop to the image/object subjects) are available for decoding: For example, why is there a volcano behind Heidegger? Why is J.G. Ballard walking a mallard? Did he really drive an Allard car? They lead to nowhere but a knife edge between complicity and value, inviting further questions about the status of those depicted, their value, the value of the paintings, or the value of Carpenter as artist. Slip and you might slit your throat.

Merlin Carpenter, Simon Lee Gallery, 2019/2020, Installation view.

Figures of ambivalence point to troubled value systems where truth may hide in plain sight. How do you judge someone who is only an image? Do you judge an artist on their last exhibition, or how seamlessly they move through the ‘system’? Perhaps the answer is to be found swirling in the weird sinewy clouds behind the oil tanker floating like a zeppelin depicted in Untitled (2019). The achievement of weightlessness as a super-heavy object is surreal, fantastical. There can be no satisfaction within such a context, it can only be imagined. We only have what is in these walls. This was also rich terrain for J.G. Ballard, for whom the moralism of the novel was highly problematic, describing it as “the greatest enemy of truth and honesty that was ever invented.” [2] The painting of the author again renders the caricature of Ballard as a seemingly ordinary man living in the London suburb of Shepperton, raising three kids, whilst also writing explicit fiction situated within the erotic, technical, and post-holocaust landscape. The ultimate outsider, Ballard was also eventually completely absorbed by the Establishment. For Carpenter, by contrast, telling the truth may be exactly the motivating force. Where market-driven painting serves as infrastructural commercial support to other less profitable practices, it operates within an accepted economic logic of quid pro quo. A certain type of painting – aesthetically decorative, obviously gestural, formulaic, large (preferably sofa-sized) – will prop up more ‘intellectual’ but less commercially viable works, with the critical work providing the cultural capital for the total gallery/institution-branding experience.

That this binary infrastructural regime is troubled with this particular exhibition of Carpenter’s paintings comes as a relief – not because they offer all to everyone, but rather because they frame this particular space of exhibition, production, and its constituent infrastructure in such a way as that it is simultaneously rendered both a readymade and a space of enquiry into the medium of painting. It does this through painting and its precise ability to digest the image object in such conditions “like a rat through a python,” [3] a bulge discernible in the smooth musculature of the rest.

Rachal Bradley is an artist and writer based in London.

Courtesy of the artist and Simon Lee Gallery. ©Merlin Carpenter; image credit: Ben Westoby

Notes

| [1] | Mallards are capable of full 360-degree panoramic vision: https://www.ducks.org/conservation/waterfowl-research-science/a-birds-eye-view. |

| [2] | Richard Kadrey and Suzanne Stefanac, “J.G. Ballard on William S. Burroughs’ Naked Truth” in: Salon, September 2, 1997, https://www.salon.com/1997/09/02/wbs/. |

| [3] | D. Harlan Wilson, J.G. Ballard, Champaign, IL 2017. |