SURREALISM AND US Jonathan Odden on “Surrealism Beyond Borders” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Koga Harue, “Umi (The Sea),” 1929

“Many Believe Surrealism is dead. […] Pure infantilism; its activity today extends throughout the world and Surrealism remains bolder and more tenacious than ever.” Suzanne Césaire’s opening line from her 1943 essay “Surrealism and Us” closes “Surrealism Beyond Borders,” the global survey of the movement recently organized by Stephanie D’Alessandro and Matthew Gale. Her words are a parathion shot aimed back at those who might misjudge the vitality of Surrealism beyond its 1920s metropole. Césaire’s Surrealism is more expansive, more liberating – a target whose center the new exhibition manages to hit with admirable accuracy.

In another wall graphic from the exhibition, the final line of Césaire’s text appears: “Surrealism – the tightrope of our hope.” As a metaphor for “Surrealism Beyond Borders,” the tightrope is, at best, tenuous. The line walked between disparate Surrealist platforms in the show does indeed require agile curation, and organizing a tentpole exhibition during a pandemic is certainly a risky, laudable spectacle. But Surrealism was always risky for those experimenting with its tools, especially artists fighting colonial powers and political pressures, as many included in the exhibition were. Still, other organizing metaphors might be more apt: the exquisite corpse, for instance, that parlor game turned automatic exercise invented by the Surrealists, whereby a sheet of paper is folded and passed around in order to create one continuous, collective drawing. Examples of exquisite corpses bookend the exhibition, beginning with a wall of historical examples and culminating with Ted Joans’s Long Distance (1976–2005), a carmen perpetuum with no less than 132 collaborators. The work reminds us that Surrealism is a maximalist enterprise, but one of contradictions, as the exquisite corpse is both made in groups and represents isolated work: interconnected work in isolation. Thus the metaphor of the exquisite corpse cleaves along its joint, at the fold that isolates and entwines. Like Deleuze’s Fold, Surrealism is “a sheet of paper which divides into an infinite number of folds or disintegrates into curved movements, each one determined by the consistency or the participation of its setting.” [1] Or, as the first wall text reads:

It refers not to a historical moment but to a movement in the truest sense; inherently dynamic, it has traveled and evolved from place to place and time to time, and continues to today.

This travel, this marauding from place to place, suggests a second metaphor: the map. Specifically, Le monde au temps des Surréalistes, which appears in the exhibition and catalogue, a map that reorients viewers from center to periphery through a distortion of the Mercator map. Half a decade before Joaquín Torres-Garcia’s América invertida (1943), this map demonstrates a unique way of moving through the global. It rejects a teleology associated with avant-gardism: Cubism, Futurism, Dada, and so on. Instead, continental drift gives way to archipelagos of coeval experimentation. A subterranean flow erupts everywhere simultaneously.

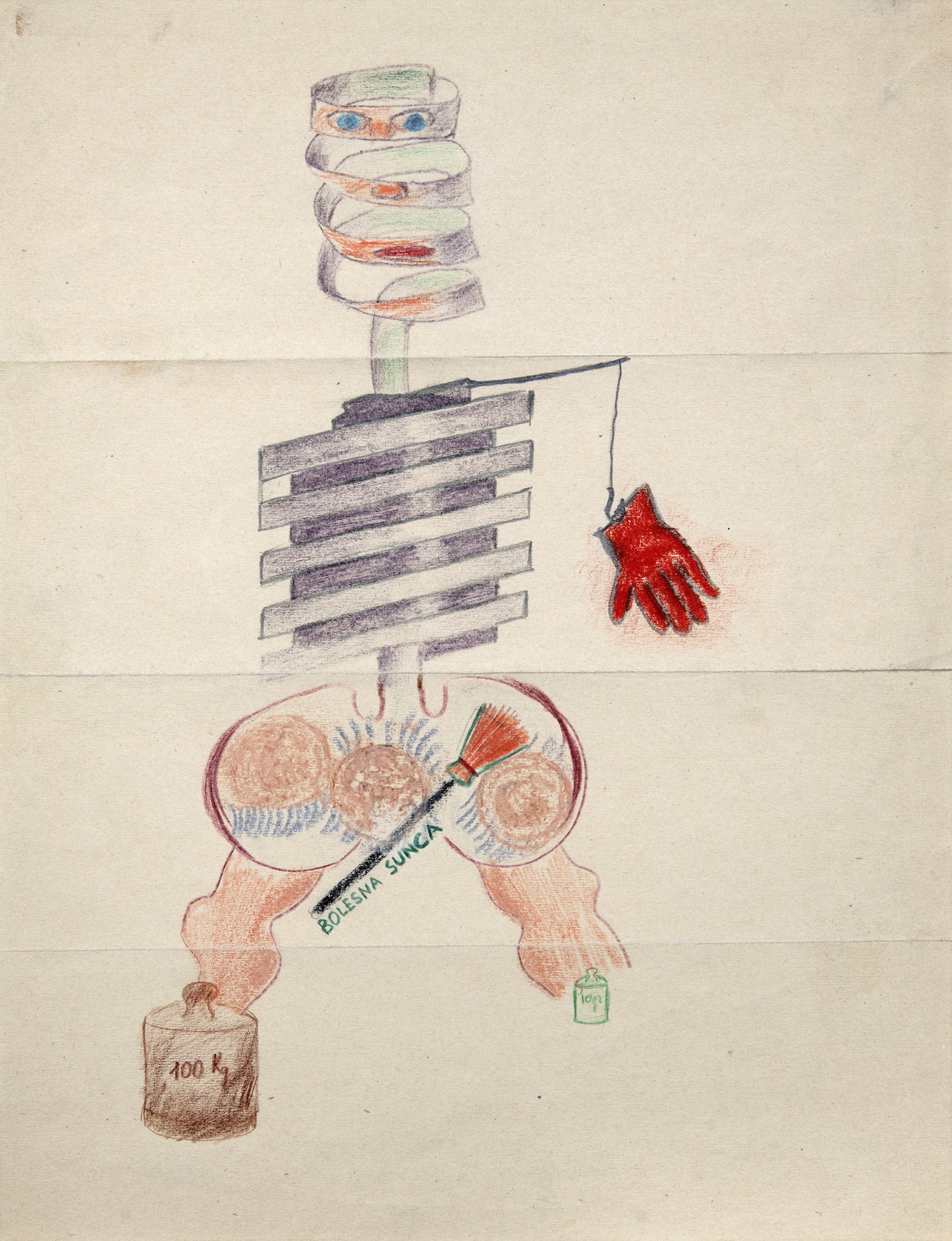

Marko Ristić, Ševa Ristić, André Thirion, Aleksandar Vučo, Lula Vučo, and Vane Živadinović Bor, “Le cadavre exquis, no. 11 (The Exquisite Corpse, no. 11),” 1930

Such coeval emergences open also to a third figure: the double. Le monde au temps des Surréalistes, for instance, which appeared in 1929 in the Belgian periodical Variétés also appeared in that same year in Contemporánoes, a Mexico City–based arts magazine. For the curators, this doubling (reproduced subtly but wonderfully as the end papers in the catalogue) reinforces the translations of Surrealism across the exhibition. There are literal doubles – double maps, double exhibition venues, a doubling of paths through the exhibition – and less literal examples – double exposures, double time, double takes, double entendres. In marshalling so many doubles one also finds the doppelgänger, the uncanny. But the uncanny is largely absent from the exhibition’s didactics, if everywhere in its form; see Claude Cahun’s mirrored self-portraits or Raúl Ruiz’s haunting short film La maleta (The Suitcase, 1963). Given the work of art historians such as Rosalind E. Krauss and Hal Foster, who have made this uncanny central, the lack is notable. [2]

There is another double of note: the balanced double, the scale, as seen for instance in Ichirō Fukuzawa’s Yoki ryōrinin (The Good Cook, 1930). “While Surrealism Beyond Borders seeks not to eradicate our familiar understanding,” the curators write, “[the exhibition] endeavors to expand and rebalance the history of the movement.” [3] This endeavor is repeated throughout: carefully weighed canonical figures against outsiders, additions and cuts for representation, quotas tallied and nations counted. Such choices explain the under-acknowledgement of Foster and Krauss – scholars who are now canonical, especially in New York. But such choices also prove at times overdetermined and underwhelming. Rebalancing does more than pursue different narratives, freeing space for the historically marginalized. It equates equality with equilibrium – equivalences that come with a caveat. And like the scale, a tool of commerce, comes the additional weight of exchange. Indeed, the logic of exchange is reflected in the exhibition as objects becoming more transitive, more prone to circulation or re-weighted placement, literally and figuratively. Mayo’s Coups de bâtons (Baton Blows, 1937), an angular, pastel-splashed painting of violent insurgence – a standout in the show – is found not in the Cairo section of the exhibition, as the work was made in that city, but in the last bay of the exhibition, “Revolution, First and Last,” where revolution becomes a more equivalent, global style – something aesthetically static across time and space. If this style is the upside to rebalancing, then we should recall André Breton on freedom and revolt: “[Surrealism] must exclude all ideas of comfortable balance and instead be conceived as continuous rebellion.” [4]

Idabel, “L’étreinte (The Embrace),” 1940

But the curators are not interested in stifling Surrealism for the sake of balance. They aim to rebalance the historical narratives of the movement, something they afford with strong curatorial decisions. The simplest of these, and most effective, is their downplaying the significance of Breton and Georges Bataille, respectively Surrealism’s so-called pope and its old enemy from within. Visitors are hard-pressed to find either name in the exhibition, and even where Breton’s name does appear – ironically, the further the exhibition travels from Paris – his influence is held at a remove. Instead, the voices of Césaire, Leonora Carrington, and others carry the show. It’s a refreshing choice, and the list of new voices is laudable, with special attention to works by Dédé Sunbeam, Alice Rahon, and Cossette Zeno. Zeno’s Ni hablar del peluquín (No Use to Talk about the Little Wig…, 1952), a fusion of biomorphic brush, fur, and auger shell browns, is fantastic. In addition, the exhibition also alternates wide- and narrow-angled views, leaning heavily on Carrington’s dictum “the task of the right eye is to peer into the telescope, while the left eye peers into the microscope.” This idea is rendered quite literally by juxtaposing long sightlines against tight vitrine work, conveying the kaleidoscopic, non-chronological nature of the movement. It is a decision, however, hindered partly by a jumble of incommensurate themes – artists, artists groups, formal themes, cities – though it is otherwise effective. More effective, and quite striking, is the curatorial decision to shift the medium focus of Surrealism. Though the curators may reject that theirs is a painting show, it cannot go unacknowledged that the first work in the exhibition, Marcel Jean’s Armoire surréaliste (Surrealist Wardrobe, 1941), was also the cover of his famous book The History of Surrealist Painting, undoubtedly one of those “familiar” histories the curators hope to rebalance. Moreover, whether it is a painting show or not, “Surrealism Beyond Borders” is decisively not a photography show. This is a shame, since the smallest sections, “Bodies of Desire” and “The Uncanny in the Everyday,” which contain a majority of the photographs in the exhibition, have some of the most arresting works. Idabel’s L’étreinte (The Embrace, 1940), a photograph of pillared ribs held fast by sinew and fat, and Ithell Colquhoun’s Scylla (1938) – a work Breton would have likely rejected for its classical reference – are fitful, erotic, and inscrutable in the best ways. But they are peripheral, back in the corners. Some works are literally beyond the exhibition: Nude Standing by the Sea (1929), a Picasso reproduced in Bataille's Documents and shown in Surrealist exhibitions in the 1930s, is installed in the permanent collection nearby, as are Yves Tanguy and Kay Sage paintings found in the catalogue.

“Surrealism Beyond Borders,” Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2021, installation view

So, what precisely is “beyond” Surrealism? Beyond, notes Homi Bhabha, is “unknowable, unrepresentable, without a return to the ‘present’ which, in the process of repetition, becomes disjunct and displaced.” [5] In the present, what should be the strongest section of the exhibition, “Haiti, Martinique, Cuba,” becomes its most contested. The Haitian artist Hector Hyppolite, whose works Ogou Feray (ca. 1945) and Papa Lauco (1945) are included in the exhibition, is given limited context; his works are largely discussed in relation to his inclusion in the 1947 exhibition of Surrealism in Paris. Haiti itself, as a nation, is lost, generalized as the Caribbean, which is a shame, since the island nation is neither peripheral to Western history nor to Surrealism: a historically maligned territory overrun by US and European incursions, it was the first nation to self-decolonize and was the site of Breton’s most convincing claim to political activism. At the same time, Haiti is not peripheral to the United States today. The exhibition’s opening coincided with one of the largest deportations of Haitian refugees in US history, and the recent response of US policy toward the nation has been isolationist. [6] Such contemporaneity should find its way into the exhibition, yet remains, it seems, beyond. In this way, the final work, Byon Yeongwon’s anti-communist response to the Korean war, Pangongyohan (Anti-Communist Female Souls, 1952), is prescient. It protests a conflict that never ended. It speaks Surrealism in the present tense. No wonder the words of Césaire on which the exhibition ends are so mocking, so bitter. No wonder Surrealism is not yet dead.

“Surrealism Beyond Borders,” the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, October 11, 2021–January 30, 2022.

Jonathan Odden is a doctoral student in the history of art at the Graduate Center, City University of New York.

Image credit: 4. Anna Marie Kellen

Notes

| [1] | Gilles Deleuze, The Fold: Leibnitz and the Baroque (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press), 231. |

| [2] | See Rosalind E. Krauss, Jane Livingston, and Dawn Ades, L'amour Fou: Photography and Surrealism (Washington, DC: Corcoran Gallery of Art; New York: Abbeville Press, 1985); Hal Foster, Compulsive Beauty (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008). |

| [3] | Stephanie D’Alessandro and Matthew Gale, “The World in the Time of the Surrealists,” in Surrealism Beyond Borders, exh. cat., eds. Stephanie D’Alessandro and Matthew Gale (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art), 10. |

| [4] | Maria Clara Bernal, “André Breton’s Anthology of Freedom: The Contagious Power of Revolt,” in Surrealism in Latin America: Vivísimo Muerto, eds. Dawn Ades, Rita Eder, and Graciela Speranza (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2012), 138. |

| [5] | Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture (New York: Routledge, 1994), 4. |

| [6] | Eileen Sullivan, “After Del Rio, Calls for Fairer Treatment of Black Migrants,” New York Times, October 19, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/19/us/politics/black-migrants-biden-border.html. |