THE DOWNWARD SPIRAL Steven Warwick on “Trigger: Gender as a Tool and a Weapon” at the New Museum, New York

With exhibitions such as “Art and Ideology” (1984), “Difference: On Representation and Sexuality” (1984), and “Damaged Goods: Desire and the Economy of the Object” (1986), New York’s New Museum, in the 1980s and ’90s, had been a central outlet for art’s intersection with politics, particularly as concerns the body. This fall, the institution – which in recent years has markedly broadened its scope – tendered a return to its more politicized past, mounting an exhibition of work that directly responds to the explosive terms of staging identity now.

Situated within the New York – London – Berlin axis across which much of the show’s constituent work has been made, writer and musician Steven Warwick gives his take on the New Museum’s “Trigger.”

Taking on a political problem set ranging from manifestations of police authority, incarceration, and physical abuse to questions of community building and non-binary sexual representation, New York’s New Museum this fall, in a self-declared return to its politically engaged founding mission, mounted a group exhibition aiming to address the social violence that pervades American (and to some degree European) culture. The show’s title, “Trigger,” while offering its own string of associations (gun control), is focused by an appended double framing of “gender,” both as “weapon” and “tool.” “Trigger,” in this latter sense, also refers to “triggering,” or that which is so potentially upsetting as to call for a warning – which could describe the better part of most political exchanges given current conditions of governance and attendant culture wars.

Across four floors, this show offers art and art-related documentation alongside performances and ephemera by, all told, some 40 artists and self-organized groups including, for example, MOTHA (Museum of Transgender Hirstory and Art, founded by Chris E. Vargas), the early ’90s New York collective fierce pussy, and A. K. Burns & A. L. Steiner’s 2010 “Community Action Centre” video, made in collaboration with a number of queer-friendly artists and performers in Burns and Steiner’s extended network. Communities figure heavily in the exhibition, whether it be Connie Samaras’s photos documenting a women-only RV retirement park in the American Southwest (“Edge of Twilight,” 2013) or Sharon Hayes’s 2013 video “Richerche: three,” referencing a Pasolini film in which the director interviewed diverse Italian communities about their views on gender, sexuality, and politics. In Hayes’s iteration (which appears in the New Museum as a single-channel video projected on a large screen), she interviews subjects attending the all-women’s college Mount Holyoke in Western Massachusetts, about the degree of sexual and political freedom within and outside of their community. Differences of opinion emerge, tense interactions follow, and the work ends with the group concluding, “We are talking about several different ‘we’s.”

But what does it mean to have a community? Can we have plurality again, in an age of conflicting populism? In “Trigger,” plurality is often sadly if unwittingly literalized as crowding of works, with few given enough space for any individual voice to be clearly heard. Hayes’s piece is a case in point: sharing quarters with works that feel more quaint or “tea and scones,” if you will, its impact is diminished and reciprocally, the more nuanced potential of the quieter art never really turns on. Does the subaltern speak when it’s drowned out in a corridor? Where artists/works do get breathing space – Wu Tsang’s video installation “Girl Talk” (2015), for instance, which does occupy its own room – the experience is a lot more dynamic. Between works of abject bodies and incarceration, Tsang’s piece provides a brief respite with supplied cushions, inviting longer engagement. Then again, I’m pretty sure this piece, seeing as it features the joyful, dancing figure of poet and theorist Fred Moten, could have held its own in the location of Hayes’s video. Maybe it’s just that despite this show’s explicit focus on community, some of the curatorially contrived relationships between works failed to inspire.

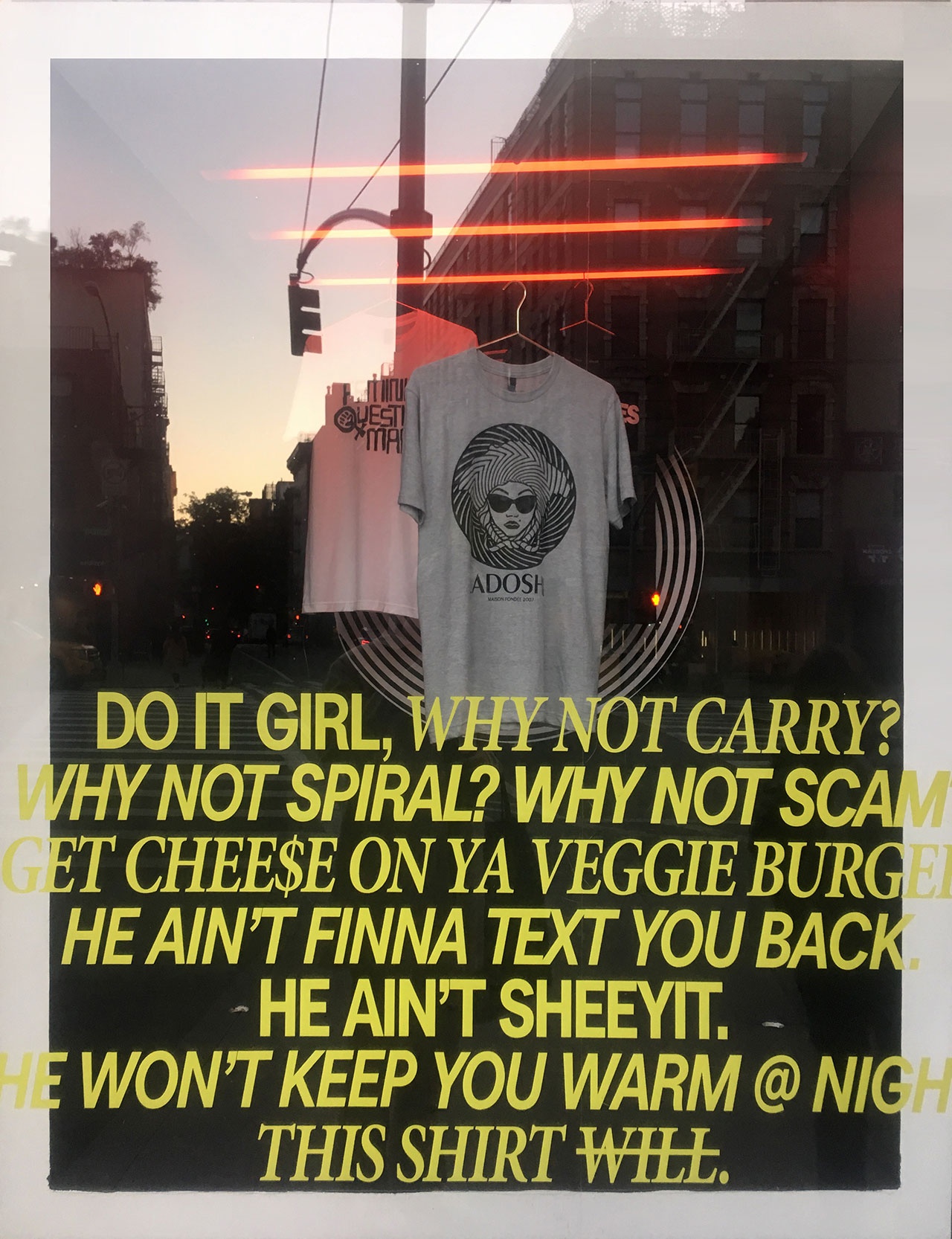

House of Ladosha, New Museum shop window, New York, 2017

House of Ladosha, New Museum shop window, New York, 2017

As if contra this forced togetherness, House of Ladosha laconically defines its sense of community through what it’s not: “We only exist in New York City.” Just like Bartleby, they prefer not to. Founded in 2007 with reference to vogue/ballroom culture, the performance/video/fashion/nightlife troupe comprises a revolving cast of members centering around La'Fem Ladosha/Just Dosha and Cunty Crawford, people who work variously in fashion, music, and studio art. Ladosha has several works on view in “Trigger,” starting with “Untitled (A Carry)” (2017), a text piece in vinyl lettering that spans the New Museum’s ground-floor entrance wall (behind the ticket and info stations, around the elevator bays, etc.). The work’s title makes me laugh out loud – carrying, i.e., somewhat similar to posing + knowingly performing something you are not (I could go on, but don’t want to Susan Sontag about it). The wall text features such witty aphorisms as “97% don’t even know what HAM is,” [1] as if implicitly asking, does it even matter if that 97% includes you? or moreover, should this 97% even really include you? Aesthetically, said aphorism reminds me of a John Giorno poem piece or of Katharine Hamnett’s iconic “58% DON’T WANT PERSHING” T-shirt, which the fashion designer wore to a meeting with PM Margaret Thatcher to protest the UK’s plans for nuclear missile armament. Ladosha’s language poses as an invitation to speak with (as in, with the same voice as ) the power structure of the museum, and in doing so also injects some much-needed humor into the show at large. By comparison, this seems to be a much queerer way of dealing with “Trigger”’s ostensible message/thesis than anything relayed by the adjacent wall text explaining how the work fits into the exhibition’s framework.

I find Ladosha’s humor highly relatable, especially in these times, for the way it gets at the general optimism fatigue many are feeling; Ladosha’s jadedness affirms a humanity for me. Cue the archival/original souvenir shirt from the musical “CATS,” altered to read “CUNTS,” hung for sale in the gift shop while others (including their appropriated Medusa Versace logo tee as well as a Ramones shirt defaced to read HORMONES) hung in the museum’s display window, which featured another piece of Ladosha’s writing. For sure, any of their works could trigger (another wall text reads: “MOST OF US DIDN’T VOTE, MOST OF THE ONES THAT DID VOTED FOR JILL STEIN RECLAIMING IS SO LATE…I HATE THE WORD RECLAIM. IT’S LIKE APPROPRIATE IT’S EVENTUALLY GOING TO END UP WITH YOU IN SHIT.”). And this is true no matter where Ladosha appears. Their video “The More You Know” (2015) occupies a corridor (between the museum’s third and fourth floors) and further, it channels rampant Kristevan/Deleuzian language – factors that quickly sink other pieces in this show. But Ladosha holds down the former by detourning the latter. When the narrator sardonically drawls, “Did you know gender can float like plasma across cognitive and somatic plains?” you know that Ladosha isn’t going to stop before they turn the box upside down and throw its (dis)contents around. One of their strengths is the way they can make something very funny alongside something more sinister, and to heightened effect: for example, the series of camera phone videos (hashtagged #policestateselfie or similar) that they made posing by security cameras in bodegas and other surveilled spaces: Why? Because if you can’t laugh you have to cry. Or a video in which a presumably fictional letter addressed “Dear Juliana” from a curator named “Becky” is read aloud in which “Becky” (a reference to the try-hard white-girl archetype named as such in Beyonce’s “Lemonade”) asks “Juliana” (ostensibly Juliana Huxtable, one of the group’s members) if Ladosha would participate in a show she’s curating because, as Becky explains, she loves their videos ; and also that, if the group isn’t available, could Juliana please suggest others [artists] she could contact? After the letter, someone on the video yells out “GAGGING ” and cracks up with laughter. Ladosha might be laughing with you or at you; the letter is read out and, at the same time, the viewer is also read.

“Trigger: Gender as a Tool and a Weapon,” New Museum, New York, installation view

“Trigger: Gender as a Tool and a Weapon,” New Museum, New York, installation view

There are other artists in “Trigger” who likewise resonate. One such case is Reina Gossett and Sasha Wortzel, whose video restages performances by Marsha P. Johnson alongside scratchy archival interview footage. (In one public account, Johnson is identified as a catalyst of Stonewall, having thrown the first “brick,” apparently a shot glass, which shattered a mirror and triggered the protests.) Gossett & Wortzel’s work is excellently installed on a screen in close proximity to Curtis Talwst Santiago’s “Black Armor” series (2017). In the latter, chainmail do-rags, helmets, and other headgear have been installed like historic museum pieces floating eerily on thin vertical poles coming up from the floor, some adorned with traditional Zulu jewelry (signs of empowerment and protection), and positioned looking into or away from a massive smashed mirror, gazes frozen. Meanwhile, Diamond Stingily’s “Kaas 4C” (2017), which consists of a single braided weave that runs down the four walls of the museum, is equally powerful in its I’m-just-going-to-leave-this-here subtle mimetic imagery and stark simplicity, bringing to mind, say, Tony Feher’s “Untitled” (1991) sculpture of a sagging bag of marbles hanging from a spare nail, their weight pinning a weathered jack-of-spades between them and the wall. Stingily’s piece ends on the ground floor, collected in a spiralling pile. Further to this and to Talwst Santiago’s do-rags, the presence of a semiotics of Afro-American bodies serves to reinforce the fact that one cannot confront discrimination in a fractured way; one cannot address sexism or homophobia without also addressing racism and vice versa. Mickalene Thomas’s sculptural video installation “Me as Muse” (2016) gets at this with brutal directness by depicting a lounging odalisque (played by the artist herself) discussing the art-historical racism of the black female body, soundtracked by a traumatic audio recording of Eartha Kitt recalling her mother being raped.

As the ideas and effects of these works accumulate during my visit, I find the name of this show still triggers me. Do its contents, its framing even come close to being enough? And also, is it merely #queer? In places, yes; in others works shine. Leidy Churchman’s 2016 “Sea Floor” painting of a smiling fish is somewhat baffling yet I can’t stop thinking about it, even now, and positively. Is there not a contradiction underpinning the nature of trying to taxonomize “queer,” which is itself inherently messy? Whilst impressive in its scope and breadth of works on display, the overall exhibition feels too vague in parts, and perhaps not in an intentional way (i.e., not productively open, non-binary, indeterminant, etc.). I guess we are talking about several different “we”s. I leave the show with mixed feelings, but not before looking once more at the Ladosha text as I exit, smiling as I go back out onto the street.

“Trigger: Gender as a Tool and a Weapon,” New Museum, New York, September 27, 2017–January 21, 2018

Title image: Leidy Churhman, “Sea Floor,” 2016

Note

| [1] | Hard as a Motherfucker |