Dreaming in Trends Michael Wang on the Louis Vuitton Foundation, Paris

While the state of art funding would seem to be in crisis, particularly throughout the European south, this past year has witnessed the opening of not one but several high profile, privately funded, public art spaces. In this issue, Texte zur Kunst – initiating a new occasional section focusing on architecture and the evolving dynamics of institutional structures – surveys three: The Louis Vuitton Foundation, Paris; the Prada Foundation, Milan; and the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, Moscow.

For artist Michael Wang, whose text opens this section, there is, in this recent wave of building, a very real correlation to the trend cycles of luxury fashion. “To be ahead of the market is the addiction of the speculator and the investor,” he writes. And indeed, what more efficient machine for ensuring that dynamic than a building able to endow, via the promise of capital, a particular framing of the always volatile present.

Like dreams, trends are strictly irrational. Like language, a trend is arbitrary yet agreed upon: a silhouette, a color palette, an exotic ingredient. A trend relies on the shared sensibility of a moment. When the moment has passed, the arbitrariness of the trend is unmasked. Stripped of its timeliness, its physical traces become at first laughable (their irrationality exposed), then finally return to the proper space of dreams, as impenetrable fragments from an indecipherable system.

Fashion, both symbolic and consumable, sets the example. Always different yet always the same, changes in style create new needs and desires. The vicissitudes of fashion facilitate the growth that the market demands. The success of the trend cycle ensured its expansion beyond fashion, accelerating product life cycles across many industries. Today, the trend cycle has expanded to nearly all areas of individual consumption: from fashion to food, furniture, entertainment, personal care, electronics, education, and architecture.

Instead of buying a new dress or pair of shoes, consumers update entire lifestyles. Life as style is the capitalist reformulation of the avant-garde merging of art and life. But if the avant-gardist ultimately imagined the destruction of art – art subsumed by life – the logic of lifestyle transforms life itself into an aesthetic project. The applied arts, the trappings of everyday life, acquire the characteristics of “fine” art. A building is a work of art. A handbag is a work of art. It is these works that are most active in the public consciousness today. It is within this expanded field of art that we can place the Louis Vuitton Foundation: a building, which the Assemblée Nationale called “a major work of art for the whole world,” that is itself a monument to the triumph of the luxury good in the global marketplace.

Olafur Eliasson, “Inside the horizon,” Louis Vuitton Foundation, Paris, 2014, installation view

Olafur Eliasson, “Inside the horizon,” Louis Vuitton Foundation, Paris, 2014, installation view

It was the luxury brand, exemplified by LVMH’s Louis Vuitton, that fully connected the logic of the trend to the structure of dreams. The luxury trend is presented as a fragment of a dream, a dream-image. Purely symbolic products, luxury goods become vehicles for the proliferation of fantasy. To render this dream visible requires an exercise in branding on an epic scale. The worlds of Louis Vuitton, Dior, Chanel, and Prada offer images in the form of elaborate spectacle: multi-million dollar runway shows, Hollywood stars, campaigns shot and directed by celebrity photographers and directors, starchitect-designed flagship stores. The dream is all-encompassing, more hallucination than idle fantasy.

The release of dream imagery into everyday life sets the luxury brand on a course first charted by the surrealists. But the social program of surrealism – its challenge to bourgeois rationality – has been neutered. It is precisely through the maintenance of polymorphously perverse desires that consumer capitalism has found an unending source of inspiration. Fashion and architecture are particularly indulgent of this consumer surrealism. Architecture aspires to unreality. It appears molded out of a single substance, or composed of paper-thin membranes rendered in crisp chiaroscuro. A vogue for optical illusion, a winking trompe l’œil, offers the momentary euphoria of disorientation. Fashion is fixated on an image of the human body as automaton or doll, caught between the living and the inanimate. But it is the arbitrary and the idiosyncratic, above all, that define dream imagery. Every label, every collection is an exercise in a new set of allusions, a new volume, a new set of textures, colors, materials. Every architect’s signature style, and indeed each building, is today an experiment in novelty and formal innovation.

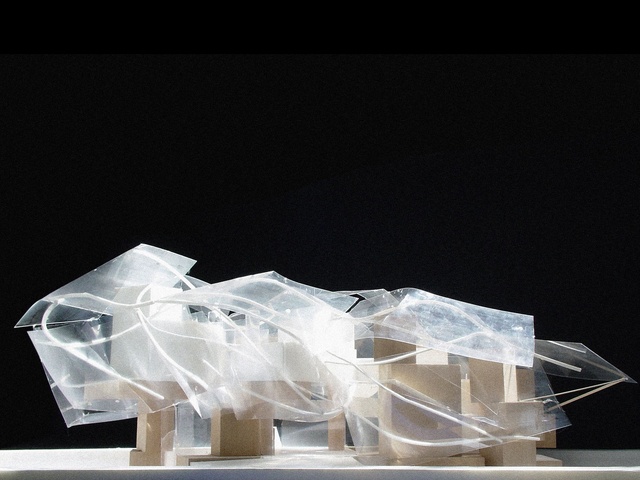

Frank Gehry, Fondation Louis Vuitton (model), 2014

Frank Gehry, Fondation Louis Vuitton (model), 2014

Gehry’s style, and the Louis Vuitton Foundation in particular, manifests all the characteristics of the trend-as-dream. The myth of Gehry’s working method suggests almost a kind of automatic sculpture in a surrealist tradition. Generative sketches give the appearance of automatic drawing: a series of cursive scrawls in which the pen barely seems to have left the surface of the paper. Physical maquettes are precisely mapped by three-dimensional modeling systems that allow for the highest degree of arbitrary formal detail to be plotted and seamlessly fabricated. In the publicity image for the foundation – dubbed the “iceberg” – the building appears almost as a send-up of late Surrealist painting, floating above an arid landscape like a phantom vessel.

While advertising has traditionally facilitated the extension and elaboration of the brand dream, the image as such is no longer sufficient. An “experience economy” demands an expansion of the brand image in time and space. Architecture, in a spectacular explosion of flagship stores in the world’s luxury capitals, became a key tool by which the luxury company shapes the experience of a brand. Apparently freed from the constraints of retail, the Louis Vuitton Foundation can more fully define the brand experience as a space apart, like the space of dreams. To experience the building is to move through it: it is a perambulatory – or somnambular – architecture. Two circulation pathways nearly double one another: one fully enclosed, linking the box-like gallery spaces, the other protected from the elements only by the arching overhang of Gehry’s glass shards. The latter path, a liminal space squeezed between the interior towers and the sheath-like façade, follows the disjointed logic of the dream: narrowing, widening, moving up or down in response to Gehry’s non-repetitive, gestural forms. Like the dream (a world within), the space feels both interior and exterior: tree ferns, bathed in glass-filtered light, sprout from stone planters, and at moments, the façade parts to reveal the city of Paris and the comparatively diminutive follies of the surrounding Parc d’Acclimitation. It is a picturesque stroll.

For the moment, at least, Gehry has given Louis Vuitton (and LVMH more generally) a new source of intoxication. The American architect even designed for the French brand a monogram handbag, the Twisted Box, which seems to come from the same topsy-turvy world, where everyday objects (or rather, objets d’art) are subjected to the very forces of torque that appear to form his building façades. In the fall of 2014, Gehry-designed sheets of curling metal, reminiscent of the Foundation’s “sails,” graced window displays of Louis Vuitton boutiques in international shopping destinations. The Foundation appears on the cover of LVMH’s 2014 Annual Report.

Left: Twisted Box by Frank Gehry for Louis Vuitton; Right: Capucines Bag by Louis Vuitton, both 2014

Left: Twisted Box by Frank Gehry for Louis Vuitton; Right: Capucines Bag by Louis Vuitton, both 2014

The elaboration of the style-of-the-moment into a hallucinatory dreamworld sets the brand experiments of the luxury industry apart, perhaps at the vanguard of increasingly immersive brand experiences to come. But with all the emphasis placed on branded experiences – in the case of Louis Vuitton, from the Gehry handbag to the Foundation building (emblazoned with an outsized Gehry-designed LV monogram, rendered in surrealist-kitsch liquid metal) – what is the role of the Foundation’s collection itself? Amid the frenzied proliferation of branded products and experiences that the applied arts so naturally accommodate, what is the place of artworks understood, primarily, through the lens of fine art?

Fine art, by aspiring to remain outside of use, fits the paradigm of the dream all too well. The products of fine art can be the most idiosyncratic, the most purely arbitrary and personal. They are, therefore, the products most perfectly positioned to sit within the trend cycle. No market research agency, advertising firm, or consultancy (with their surveys and focus groups and quantitative analysis) is equipped to create this kind of irrational content.

But it is not any art that is at stake here. It is, largely, that art which is deemed “contemporary,” art that, like the trend, finds visibility only in relation to the present. The excitement and euphoria of trends borrows from, and overtakes, the avant-garde pursuit of the new. Like a drug that awakens an inner world – an exteriority that is already inside – a trend promises escape without disrupting the smooth operation of the system. In fact, within the apparently closed circuit of the market, setting a trend (going viral) masquerades as vanguardism. The desire for the “contemporary” is to partake in the drug that is shared, at first exclusively, then by all. The greatest respect is accorded to the vanguards of the market. The trend forecaster. The cool hunter. Who wants what first? To be ahead of the market is the addiction of the speculator and the investor. A language of invention, radicality, innovation, and rupture is now part of the lexicon of marketing, not revolution. LVMH chair Bernard Arnault has said: “What I like is the idea of transforming creativity into profitability.”

An open letter in protest of the public celebration of the private Louis Vuitton Foundation, signed by, among others, Georges Didi-Huberman, Giorgio Agamben, and Jean-Luc Nancy, decried the artistic “philanthropy” espoused by luxury tycoons as a new form of entrepreneurialism. Art, in fact, has become the most perfect commodity: “For a society that dreams of rapidity, and is indexed on fluxes, art has the very profile of the object of desire.” Within the luxury industry, art is not merely an object to be desired: it is productive of desire itself. The luxury industry has harnessed the fine arts as a machine for the production of dreams. Art acts as the market’s necessary other; the unconscious to the market’s consciousness. Through the apparatus of the trend, the dreamworld of the consumer collective breaks into the light of day.

Notes

| [1] | Frank Gehry, Louis Vuitton Fondation, Paris. Photo: Iwan Baan, 2014 |